TL;DR

A leukemoid reaction is a benign, reactive process characterized by a marked increase in white blood cells (leukocytosis, often >50,000/µL) with immature myeloid forms (left shift), but it is not a malignancy.

- Physiological Basis ▾: It represents an exaggerated, but appropriate, bone marrow response to severe stress, infection, or inflammation, mediated by cytokines like G-CSF and GM-CSF.

- Causes ▾: Common causes include severe bacterial, viral, or fungal infections, extensive inflammation (e.g., trauma, burns, pancreatitis), certain malignancies (paraneoplastic syndromes), and drug-induced effects (e.g., corticosteroids, G-CSF administration).

- Symptoms ▾: Primarily reflect the underlying cause (e.g., fever, pain, signs of infection). Importantly, it lacks leukemia-specific symptoms like significant splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, or unexplained bleeding/bruising.

- Laboratory Investigations ▾: Key diagnostic tools include CBC with differential (marked leukocytosis, left shift, absence of blasts), peripheral blood smear (toxic granulation, Döhle bodies), elevated Leukocyte Alkaline Phosphatase (LAP) score, and absence of the Philadelphia chromosome (BCR-ABL1 fusion gene). Bone marrow examination is performed if malignancy is suspected.

- Differential Diagnosis ▾: Crucially distinguished from Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) by LAP score, Philadelphia chromosome status, and basophilia/eosinophilia. Other myeloproliferative neoplasms and acute leukemias must also be considered and ruled out.

- Treatment and Management ▾: The focus is entirely on treating the underlying cause (e.g., antibiotics for infection, surgery for abscesses, chemotherapy for malignancy). The leukemoid reaction itself resolves once the primary condition is managed.

*Click ▾ for more information

What is a leukemoid reaction?

A leukemoid reaction is a reactive, benign process characterized by marked leukocytosis (typically >50,000/µL), often with a left shift and the presence of immature myeloid forms (myelocytes, metamyelocytes).

It is an exaggerated but appropriate bone marrow response to severe stress or infection, and it is crucial to distinguish it from leukemia, which is a malignant condition.

Physiological Basis of a Leukemoid Reaction

When the body encounters significant physiological stress, such as a severe infection, extensive inflammation, or tissue damage, the immune system signals the bone marrow to dramatically increase the production of white blood cells, specifically neutrophils.

This accelerated production is mediated by various cytokines and growth factors.

- Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor (G-CSF): This is a crucial cytokine that directly stimulates the production, maturation, and release of granulocytes (neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils) from the bone marrow. In severe conditions, tissues and immune cells produce large amounts of G-CSF.

- Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor (GM-CSF): Similar to G-CSF, GM-CSF also promotes the proliferation and differentiation of myeloid progenitor cells into granulocytes and macrophages.

- Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-alpha): These are pro-inflammatory cytokines that contribute to the overall systemic inflammatory response. They can indirectly stimulate granulopoiesis by enhancing the production of G-CSF and GM-CSF, and by directly influencing bone marrow stem cells. The combined effect of these cytokines pushes the bone marrow into overdrive, leading to the rapid proliferation and release of not just mature neutrophils but also immature forms like myelocytes and metamyelocytes, which is characteristic of the “left shift” seen in leukemoid reactions.

These signals stimulate the myeloid progenitor cells in the bone marrow to proliferate and differentiate at a much higher rate than normal. This intense demand leads to the rapid release of not only mature neutrophils but also a significant number of immature forms (like myelocytes and metamyelocytes) into the peripheral blood, resulting in the characteristic “left shift” and very high white blood cell counts seen in a leukemoid reaction.

It’s considered “appropriate” because it’s a physiological attempt by the body to combat the severe underlying insult, even if the response is robust.

Differentiation from Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) at a Cellular Level

An important aspect of understanding the pathophysiology of a leukemoid reaction is distinguishing it from myeloproliferative neoplasms like Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML).

- Leukemoid Reaction (Polyclonal): The myeloid cell expansion in a leukemoid reaction is polyclonal. This means that the increased white blood cells originate from many different, healthy myeloid progenitor cells in response to a systemic stimulus. The cells are functionally normal, and the process resolves once the underlying cause is treated.

- Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) (Clonal): In contrast, CML is a clonal disorder. It arises from a single abnormal hematopoietic stem cell that has undergone a specific genetic mutation (the Philadelphia chromosome, leading to the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene). This single abnormal clone proliferates uncontrollably, leading to an accumulation of functionally impaired myeloid cells. This is why CML is a malignancy, while a leukemoid reaction is a benign, reactive process.

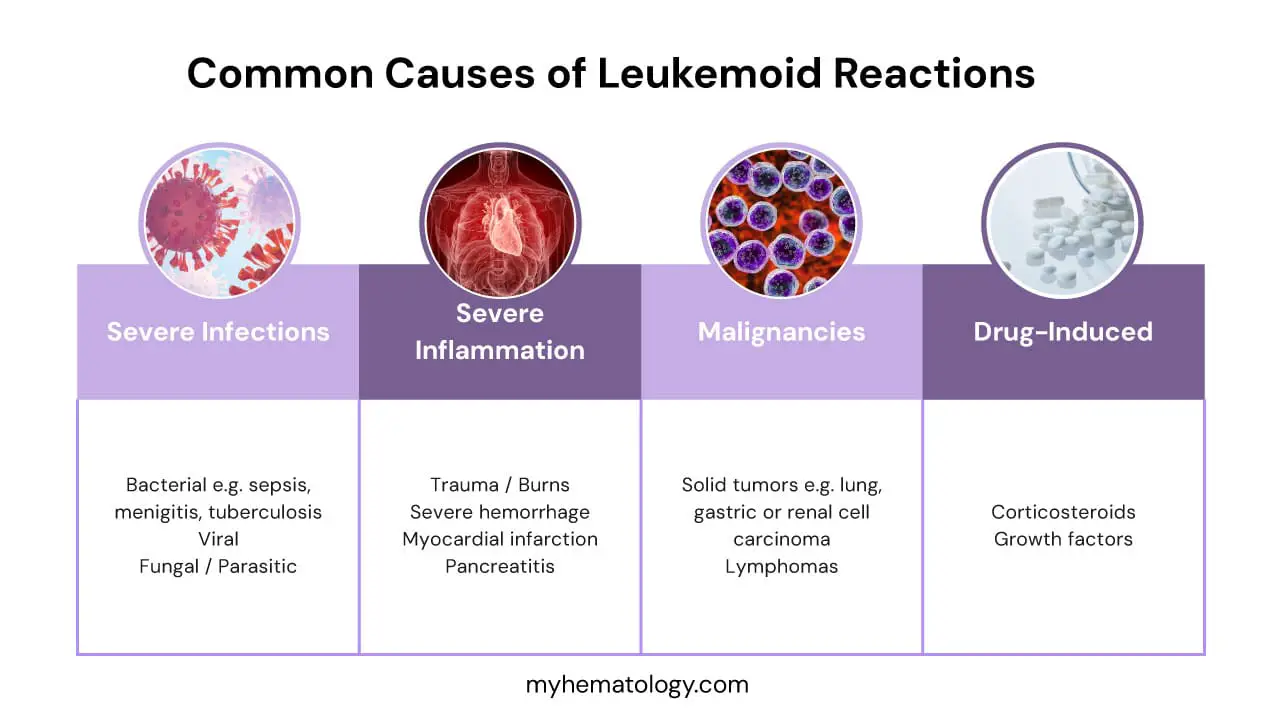

Causes of Leukemoid Reaction

The causes of a leukemoid reaction are diverse, stemming from various conditions that trigger a significant physiological stress response in the body, leading to an exaggerated bone marrow output of white blood cells.

Severe Infections

Infections are among the most frequent causes of leukemoid reactions, as the body mounts a robust immune defense.

- Bacterial Infections: These are particularly potent triggers.

- Sepsis: A life-threatening condition caused by the body’s overwhelming response to infection.

- Clostridium difficile infection: Severe gut infection often leading to significant inflammation.

- Pneumonia: Especially severe bacterial pneumonia.

- Meningitis: Inflammation of the membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord.

- Tuberculosis: A chronic bacterial infection that can cause a strong inflammatory response.

- Viral Infections: While less common than bacterial, some severe viral infections can induce a leukemoid reaction. A notable recent example is severe cases of COVID-19, where the systemic inflammatory response can be profound.

- Fungal/Parasitic Infections: Deep-seated fungal infections or certain parasitic infections (like severe malaria) can also, though less frequently, lead to a leukemoid response due to the intense immune activation they provoke.

Severe Inflammation/Tissue Necrosis

Any condition involving extensive tissue damage or widespread inflammation can stimulate the bone marrow.

- Trauma/Burns: Extensive physical trauma or severe burns cause massive tissue destruction and a systemic inflammatory response, releasing cytokines that stimulate granulopoiesis.

- Severe Hemorrhage/Hemolysis: Acute, significant blood loss or rapid destruction of red blood cells (hemolysis) can act as a profound stressor, prompting the bone marrow to respond.

- Myocardial Infarction (Heart Attack): The necrosis of heart muscle tissue following a heart attack triggers a significant inflammatory cascade.

- Pancreatitis: Acute inflammation of the pancreas can be severe and lead to systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), often accompanied by leukemoid features.

Malignancies (Paraneoplastic Syndromes)

Some cancers can produce substances that mimic the body’s natural growth factors, leading to a leukemoid reaction as a paraneoplastic syndrome.

- Solid Tumors: Certain solid tumors can ectopically produce cytokines like G-CSF, directly stimulating the bone marrow. Examples include:

- Lung carcinoma

- Gastric carcinoma

- Renal cell carcinoma

- Melanoma

- Lymphomas: While less common than with solid tumors, some lymphomas can also be associated with leukemoid reactions.

Drug-Induced

Certain medications can directly or indirectly stimulate white blood cell production.

- Corticosteroids: These drugs, commonly used as anti-inflammatories, can cause a significant increase in neutrophil count by affecting their release from the bone marrow and decreasing their margination.

- Growth Factors (G-CSF, GM-CSF administration): These are therapeutic agents given to patients (e.g., after chemotherapy) to boost white blood cell counts. Their administration will directly induce a leukemoid-like state.

Other Rare Causes

- Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA): A severe complication of diabetes characterized by high blood sugar and acidosis, which can induce a significant stress response.

- Eclampsia: A severe complication of pregnancy characterized by seizures and high blood pressure, also a profound physiological stressor.

Clinical Presentation and Symptoms of A Leukemoid Reaction

The symptoms of a leukemoid reaction are primarily those of the underlying condition that is triggering the exaggerated white blood cell response. The leukemoid reaction itself typically does not cause specific symptoms, but rather is a laboratory finding that indicates a significant physiological stressor.

Symptoms Related to Underlying Cause

The most crucial point is that patients with a leukemoid reaction will present with the signs and symptoms of the primary disease process. This is because the leukemoid reaction is a response to that underlying condition.

If the cause is a severe bacterial infection (like pneumonia or sepsis), the patient will exhibit symptoms such as:

- Fever and chills

- Cough and shortness of breath (for pneumonia)

- Localized pain or swelling (for an abscess)

- General malaise, fatigue, and weakness

- Signs of systemic inflammation (e.g., rapid heart rate, low blood pressure in sepsis)

If the cause is severe inflammation or tissue necrosis (e.g., pancreatitis or extensive burns), symptoms would include:

- Severe abdominal pain (for pancreatitis)

- Pain, redness, and swelling at the site of trauma or burns

- Signs of systemic inflammatory response

If it’s due to a malignancy acting as a paraneoplastic syndrome, the patient might have symptoms related to the tumor itself (e.g., weight loss, fatigue, specific organ dysfunction depending on the tumor location).

Therefore, the clinician’s focus is usually on identifying and addressing these primary symptoms to diagnose the underlying cause.

Absence of Leukemia-Specific Symptoms

A critical differentiating factor for a leukemoid reaction is the absence of symptoms typically associated with leukemia. This helps distinguish a benign, reactive process from a malignant one. In a leukemoid reaction, you generally would not see:

- Splenomegaly: Enlargement of the spleen, which is common in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) due to extramedullary hematopoiesis.

- Lymphadenopathy: Enlarged lymph nodes, often seen in various leukemias and lymphomas.

- Bleeding or Bruising: These are common in acute leukemias due to bone marrow suppression leading to thrombocytopenia (low platelet count) or dysfunctional platelets.

- Bone pain: While some severe infections can cause generalized aches, specific bone pain due to marrow expansion is more characteristic of leukemia.

Potential for Hyperviscosity Symptoms (Rare)

While rare, if the leukocyte counts become extremely high (e.g., >100,000-200,000/µL), there is a theoretical potential for hyperviscosity syndrome. This occurs when the sheer number of white blood cells makes the blood thicker, impairing blood flow, particularly in microvasculature. Symptoms of hyperviscosity can include:

- Neurological symptoms: Headaches, dizziness, confusion, visual disturbances, or even stroke-like symptoms.

- Respiratory symptoms: Shortness of breath.

- Priapism (prolonged erection).

- Visual impairment due to retinal vein engorgement.

However, hyperviscosity is much less common in leukemoid reactions compared to acute leukemias, primarily because the white blood cells in a leukemoid reaction are more mature and deformable than the rigid, immature blasts seen in acute leukemia, which are more prone to causing sludging in capillaries.

Key Laboratory Investigations for Leukemoid Reaction Diagnosis

Complete Blood Count (CBC) with Differential

This is the primary initial test.

- Marked Leukocytosis: The white blood cell count is typically very high, usually above 50,000/µL, and sometimes even exceeding 100,000/µL.

- Left Shift: The differential count will show an increase in immature neutrophil forms, such as bands, metamyelocytes, and myelocytes, and occasionally promyelocytes.

- Basophilia/Eosinophilia: These are usually absent or only mildly present, which helps differentiate from certain malignant conditions like Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML).

- Red Blood Cells/Platelets: These are generally normal or reflect the underlying condition (e.g., anemia of chronic disease).

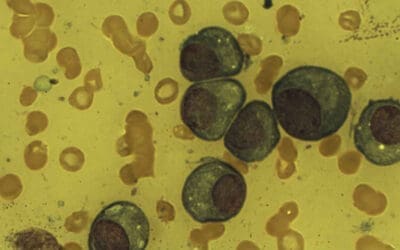

Peripheral Blood Smear

This microscopic examination of blood cells is very important.

- Toxic Granulation, Döhle Bodies, Cytoplasmic Vacuolation: These are characteristic morphological changes in neutrophils that indicate infection or severe inflammation.

- Absence of Blasts: Crucially, there should be very few or no blasts (immature white blood cells, typically less than 5%), which helps rule out acute leukemia.

- Normal Platelet Morphology: Platelets usually appear normal.

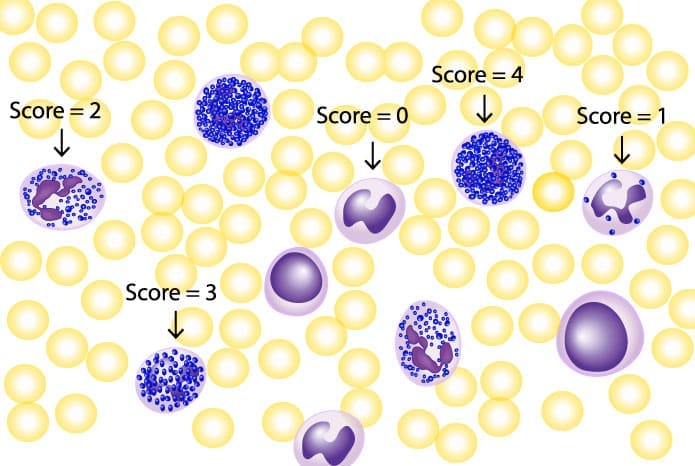

Leukocyte Alkaline Phosphatase (LAP) Score

This test is vital for differentiating a leukemoid reaction from CML.

- Elevated in Leukemoid Reaction: The LAP score will be high.

- Low in CML: In contrast, the LAP score is typically low in CML.

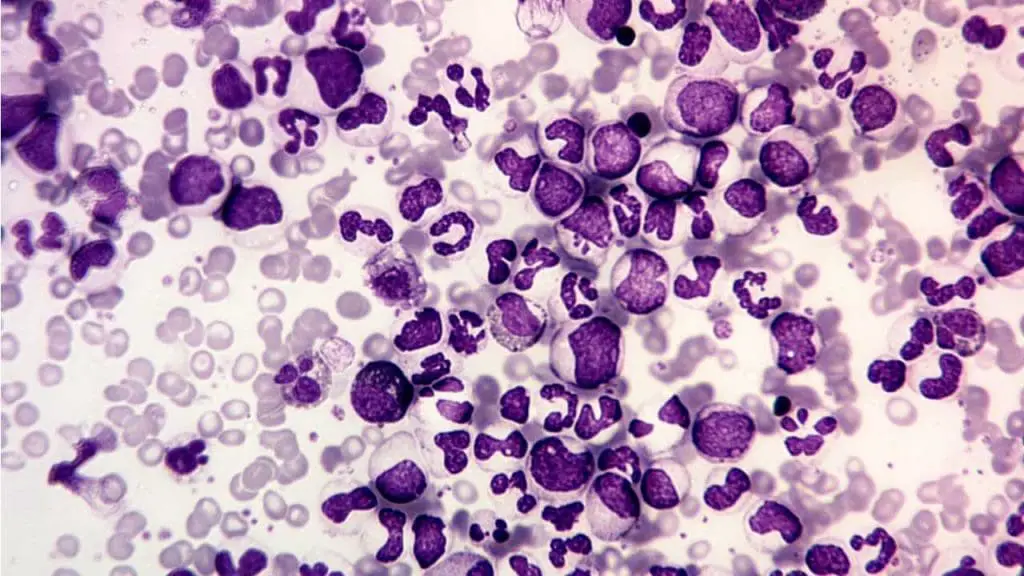

Bone Marrow Examination (when indicated)

This is performed if there’s suspicion of a malignant process or if the diagnosis remains unclear.

- Hypercellularity with Myeloid Hyperplasia: The bone marrow will show increased cellularity due to an overproduction of myeloid cells.

- Maturation Arrest: This is usually absent or minimal, meaning the cells are maturing appropriately, unlike in some leukemias.

- Absence of Clonal Abnormalities: There will be no evidence of abnormal cell clones.

Genetic Testing (when CML is suspected)

This is specifically done to rule out CML.

- Molecular Testing (PCR for BCR-ABL1): Used to detect the fusion gene. This chromosomal abnormality is absent in leukemoid reactions but is the hallmark of CML.

Inflammatory Markers

- CRP (C-reactive protein) and ESR (Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate): These are often elevated, supporting an underlying inflammatory or infectious cause.

Cultures and Imaging

These are not direct investigations for the leukemoid reaction itself, but are essential for identifying the underlying cause.

- Cultures: To identify bacterial, fungal, or viral pathogens.

- Imaging (e.g., X-rays, CT scans): To locate sources of infection, inflammation, or malignancy.

Differential Diagnosis for Leukemoid Reaction

Chronic Myeloid Leukemia

This table summarizes the crucial differences between a leukemoid reaction and Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML), which are often confused due to similar presentations of high white blood cell counts.

| Feature | Leukemoid Reaction | Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) |

| Nature of Process | Reactive, benign, polyclonal | Malignant, clonal myeloproliferative neoplasm |

| Leukocyte Count | Marked leukocytosis (typically >50,000/µL, can be >100,000/µL) | Marked leukocytosis (often very high, similar to LR) |

| Left Shift | Prominent (bands, metamyelocytes, myelocytes, promyelocytes) | Prominent (all stages of myeloid maturation, including basophils/eosinophils) |

| Blasts in Peripheral Blood | Absent or very few (<5%) | Variable; few in chronic phase, significantly increased in accelerated phase/blast crisis (>20% in blast crisis) |

| Toxic Granulation/Döhle Bodies/Vacuolation | Often present in neutrophils | Generally absent |

| Leukocyte Alkaline Phosphatase (LAP) Score | Elevated | Low or Absent |

| Philadelphia Chromosome (BCR-ABL1) | Absent | Present (hallmark genetic abnormality) |

| Basophilia/Eosinophilia | Usually absent or mild | Often prominent |

| Splenomegaly | Usually absent or mild | Common and often significant |

| Symptoms | Primarily those of the underlying cause | Often insidious onset; can include fatigue, weight loss, abdominal fullness (due to splenomegaly) |

| Bone Marrow | Hypercellularity with myeloid hyperplasia, no maturation arrest | Hypercellularity with myeloid hyperplasia, often with increased blasts, megakaryocytes |

| Prognosis | Depends on underlying cause; resolves with treatment | Chronic but progressive; requires specific targeted therapy |

Myeloproliferative Neoplasms (MPNs)

While less frequently confused with leukemoid reactions than CML, other MPNs are also clonal disorders of the myeloid lineage that can present with elevated blood counts.

- Polycythemia Vera (PV): Primarily characterized by erythrocytosis (increased red blood cells), but can also have leukocytosis and thrombocytosis (increased platelets). The key differentiator is the red cell mass and often the presence of the JAK2 V617F mutation.

- Essential Thrombocythemia (ET): Primarily characterized by thrombocytosis, but can have mild leukocytosis.

- Primary Myelofibrosis (PMF): Can present with varying blood counts, often with leukoerythroblastosis (immature red and white blood cells) and teardrop cells on the peripheral smear, along with significant splenomegaly and bone marrow fibrosis.

These are differentiated from leukemoid reactions by their clonal nature, specific genetic mutations (e.g., JAK2, CALR, MPL), and typical clinical features.

Severe Infection/Sepsis (without leukemoid features)

It is important to distinguish a true leukemoid reaction (exaggerated response) from a typical, but still significant, leukocytosis seen in many severe infections or sepsis.

In a typical severe infection, the white blood cell count might be elevated (e.g., 15,000-30,000/µL) with a left shift, but it generally does not reach the extreme levels (>50,000/µL) characteristic of a leukemoid reaction.

The presence of marked immature forms (myelocytes, metamyelocytes) in high numbers is more indicative of a leukemoid reaction.

Acute Leukemia

While generally distinct, it’s crucial to exclude acute leukemia, especially if there are any blasts present.

Acute Leukemia is characterized by the presence of >20% blasts in the bone marrow or peripheral blood. The white blood cell count can be high, normal, or even low. Patients often present with symptoms of bone marrow failure (anemia, thrombocytopenia leading to bleeding, neutropenia leading to infections).

Leukemoid Reaction by definition, has very few or no blasts (<5%).

Treatment and Management of Leukemoid Reaction

The core principle of treating and managing a leukemoid reaction is to focus entirely on addressing the underlying cause. The leukemoid reaction itself is a reactive, benign process and does not require specific treatment. Once the primary condition is resolved, the exaggerated white blood cell count will naturally return to normal.

- If a bacterial infection is the cause, appropriate antibiotics are administered.

- If there’s an abscess or necrotic tissue, surgical intervention may be necessary.

- For leukemoid reactions caused by malignancies (paraneoplastic syndromes), chemotherapy or radiation targeting the tumor would be the treatment.

- If a medication is identified as the cause, discontinuation of the offending drug is required.

Regular serial Complete Blood Counts (CBCs) are performed to track the white blood cell count and observe its resolution, confirming that the treatment for the underlying cause is effective.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the basic difference between leukemia and a leukemoid reaction?

The basic difference between a leukemoid reaction and leukemia (specifically CML as detailed in the table) lies in their nature.

A leukemoid reaction is a reactive, benign, and polyclonal process where the bone marrow produces an exaggerated but appropriate number of white blood cells in response to an underlying stress or condition.

Whereas leukemia, such as Chronic Myeloid Leukemia, is a malignant, clonal myeloproliferative neoplasm arising from an abnormal, uncontrolled proliferation of a single myeloid stem cell.

What is a leukemoid reaction Down syndrome?

Babies born with Down syndrome (Trisomy 21) can indeed present with a condition often referred to as a “transient leukemoid reaction” or, more precisely, Transient Abnormal Myelopoiesis (TAM).

Similar to a general leukemoid reaction, there’s a very high white blood cell count, sometimes with immature myeloid cells (blasts) in the peripheral blood. A key characteristic is that this elevated white cell count often resolves spontaneously within the first few weeks or months of life without specific treatment.

TAM can clinically and morphologically resemble acute myeloid leukemia (AML), particularly acute megakaryoblastic leukemia (AML-M7), making accurate diagnosis crucial. It is strongly associated with acquired mutations in the GATA1 gene, which are found specifically in the trisomic cells (cells with an extra copy of chromosome 21).

While most cases of TAM resolve, a significant percentage (around 20-30%) of infants with TAM may later progress to full-blown myeloid leukemia of Down syndrome (ML-DS) within the first few years of life. Therefore, close monitoring is essential.

Is leukemoid reaction the same as neutrophilia?

A leukemoid reaction is not the same as neutrophilia, but rather a severe form of it.

Neutrophilia simply refers to an increase in the absolute number of neutrophils in the blood. A leukemoid reaction is characterized by a marked leukocytosis (typically white blood cell count >50,000/µL), which is predominantly due to an increase in neutrophils, but critically also includes a prominent left shift with the presence of immature myeloid forms (like myelocytes and metamyelocytes).

Therefore, while all leukemoid reactions involve neutrophilia, not all cases of neutrophilia constitute a leukemoid reaction; the latter implies a much more exaggerated and specific bone marrow response.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Portich, J. P., & Faulhaber, G. A. M. (2020). Leukemoid reaction: A 21st-century cohort study. International journal of laboratory hematology, 42(2), 134–139. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijlh.13127

- Sakka, Vissaria et al. (2006) An update on the etiology and diagnostic evaluation of a leukemoid reaction. European Journal of Internal Medicine, Volume 17, Issue 6, 394 – 398.

- Hongwei H. Leukemoid reaction with severe thrombocytopenia in a dying patient: a case report and literature review. Journal of International Medical Research. 2021;49(1). doi:10.1177/0300060520974257

- Hussein, T. W., Almualem, Z. D., Almualem, F. D., Zainaldeen, B. A., & Alshaikh, Z. J. (2023). Leukemoid Reaction With Severe Diabetic Ketoacidosis. Cureus, 15(12), e50325. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.50325