TL;DR

Primary myelofibrosis is a rare chronic blood cancer originating in the bone marrow. Characterized by abnormal blood cell production, bone marrow fibrosis (scarring), and enlarged spleen.

Pathogenesis ▾

Caused by clonal mutations in a hematopoietic stem cell, leading to overproduction of abnormal blood cells and bone marrow fibrosis due to inflammatory mediators.

Epidemiology ▾

- Prevalence: Around 1-2 cases per 100,000 individuals.

- Incidence: Approximately 0.5-1 case per 100,000 individuals annually.

- Age and gender: More common in older adults and slightly more prevalent in men.

- Geographical variations: Slightly higher rates in Europe and North America compared to other regions.

Risk Factors and Causes ▾

- Age: Risk increases significantly with age.

- Environmental factors: Exposure to certain chemicals and ionizing radiation.

- Family history: Having a close relative with MPNs.

- Genetic mutations: JAK2, CALR, and MPL mutations are the main culprits.

Signs and Symptoms ▾

- Early: Fatigue, weakness, night sweats, unexplained weight loss.

- Later: Enlarged spleen, bone pain, easy bruising/bleeding, symptoms from low blood cell counts (anemia, infections).

Complications ▾

- Infections, transformation to AML, bleeding/thrombosis, portal hypertension, extramedullary hematopoiesis, bone pain, fatigue, and splenomegaly-related symptoms.

Diagnosis ▾

- Laboratory investigations: Complete blood count, peripheral blood smear, bone marrow aspiration and biopsy, molecular testing.

- Diagnostic criteria: Based on a combination of major and minor criteria, including bone marrow fibrosis, splenomegaly, and other factors.

Treatment and Management ▾

- Goals: Symptom management, slowing disease progression, and prolonging survival.

- Treatment options:

- Supportive care (transfusions, hydroxyurea, pain management, aspirin)

- JAK inhibitors (ruxolitinib, fedratinib)

- Interferon-alpha

- Splenectomy

- Low-dose radiation

- Stem cell transplantation (rarely)

- Prognosis: Varies depending on age, mutations, and other factors. DIPSS Plus score helps assess risk stratification.

*Click ▾ for more information

Introduction

Primary myelofibrosis (PMF) is a rare chronic blood cancer that originates in the bone marrow. It is characterized by:

- Abnormal blood cell production: The bone marrow produces too many abnormal blood cells, leading to imbalances in the different cell types (red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets).

- Bone marrow fibrosis: Scarring (fibrosis) develops within the bone marrow, making it difficult for healthy blood cells to be produced.

- Enlarged spleen (splenomegaly): The spleen tries to compensate for the abnormal blood cell production, leading to its enlargement.

Classification

Primary myelofibrosis (PMF) is classified as a myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN). MPNs are a group of blood cancers characterized by the overproduction of one or more types of blood cells. Other MPNs include:

Primary myelofibrosis (PMF) is considered a primary MPN because it arises on its own, without developing from another blood disorder.

Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology

The exact cause of primary myelofibrosis (PMF) is not fully understood, but it arises from the development of acquired (not inherited) genetic mutations in the DNA of hematopoietic stem cells within the bone marrow. These mutated stem cells and their progeny lead to an overproduction of abnormal blood cells, particularly megakaryocytes (precursors of platelets). These abnormal megakaryocytes release signaling molecules that stimulate fibroblasts, specialized cells in the bone marrow, to produce excessive collagen and other fibers, resulting in the characteristic scarring or fibrosis.

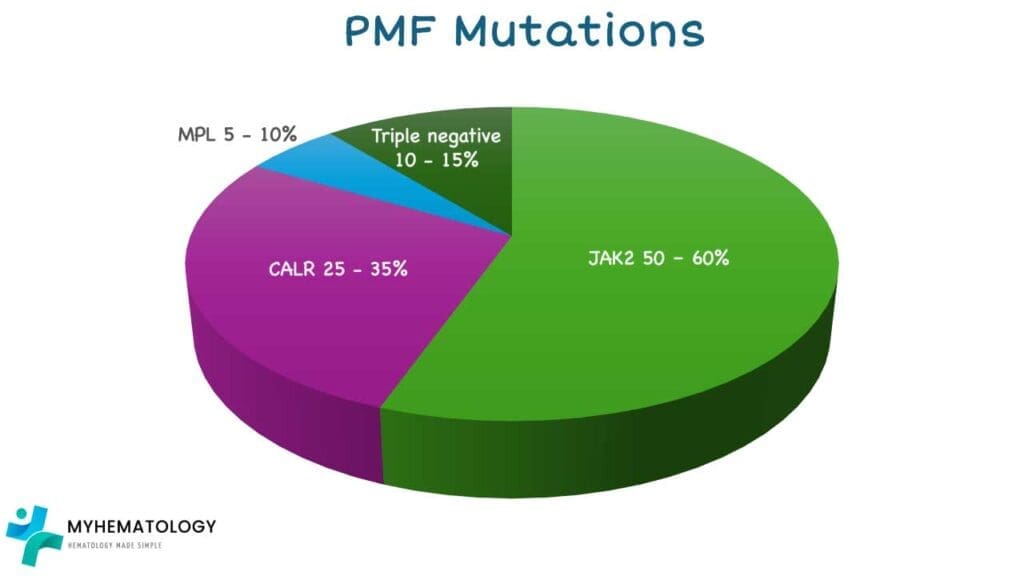

Several gene mutations have been frequently identified in individuals with PMF, with the most common being:

- JAK2 (Janus Kinase 2) mutation: Found in approximately 50-60% of PMF patients. The most frequent JAK2 mutation is V617F, which leads to the JAK2 protein being constitutively active, promoting excessive blood cell production and contributing to fibrosis.

- CALR (Calreticulin) mutation: Present in about 25-35% of PMF patients who do not have the JAK2 mutation. These mutations, often insertions or deletions in the CALR gene, result in an altered calreticulin protein that can also activate signaling pathways leading to MPN development.

- MPL (Myeloproliferative Leukemia virus oncogene) mutation: Found in a smaller proportion of PMF patients (around 5-10%) who are negative for both JAK2 and CALR mutations. MPL encodes the thrombopoietin receptor, and mutations in this gene can also lead to its overactivation, driving the disease.

Around 10-15% of PMF patients do not have any of these three common mutations and are referred to as “triple-negative.” Other less common gene mutations can also be present and are being actively researched for their role in PMF pathogenesis and prognosis.

While these genetic mutations are key drivers of PMF, the specific triggers that cause these mutations to occur in the first place remain largely unknown. In rare instances, exposure to certain industrial chemicals like benzene or high doses of radiation has been suggested as potential risk factors. It’s also important to note that in a small subset of individuals, PMF can evolve from other myeloproliferative neoplasms like essential thrombocythemia (ET) or polycythemia vera (PV).

Epidemiology of PMF

- Prevalence: Primary myelofibrosis (PMF) is a relatively rare blood cancer. The estimated global prevalence is around 1-2 cases per 100,000 individuals.

- Age and Gender Distribution: Primary myelofibrosis (PMF) typically occurs in older adults, with the average age of diagnosis being around 65-70 years. The disease is more common in men compared to women, with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 1.5:1.

- Geographical Variations: The incidence of primary myelofibrosis (PMF) shows some variations across different geographical regions with slightly higher rates are observed in Europe and North America compared to other regions.

Risk Factors and Causes of PMF

Risk Factors

While the exact cause of primary myelofibrosis (PMF) remains unknown, several factors are considered risk factors for developing the disease:

- Age: The risk of primary myelofibrosis (PMF) increases significantly with age, with the highest incidence seen in individuals over 60 years old.

- Exposure to certain chemicals: Long-term exposure to benzene (found in some industrial settings and gasoline) and certain other solvents has been linked to an increased risk of PMF.

- Ionizing radiation: Exposure to high levels of ionizing radiation, such as that from atomic bombs or certain medical procedures, can also increase the risk.

- Family history: Having a close relative (parent, sibling, child) with MPNs, including primary myelofibrosis (PMF), increases the risk, though it is still relatively low.

Causes

The specific cause of primary myelofibrosis (PMF) is still unknown. However, it is believed to involve a combination of genetic and environmental factors:

- Genetic mutations: As discussed earlier, mutations in genes like JAK2, CALR, and MPL are found in the majority of primary myelofibrosis (PMF) cases. These mutations lead to dysregulation of cell growth and survival pathways, ultimately contributing to the development of the disease.

- Environmental factors: While not fully understood, exposure to certain environmental toxins and chemicals may play a role in triggering these genetic mutations or promoting the development of primary myelofibrosis (PMF) alongside the mutations.

Signs and Symptoms of PMF

The primary myelofibrosis (PMF) symptoms can be varied and non-specific in the early stages, often making it difficult to diagnose. However, as the disease progresses, the symptoms become more pronounced.

Early Primary Myelofibrosis Symptoms

- Fatigue: This is a common and often the first noticeable myelofibrosis symptom. It can be described as a feeling of tiredness, exhaustion, and lack of energy that persists even after adequate rest.

- Weakness: This can manifest as a feeling of decreased muscle strength and difficulty performing daily activities.

- Night sweats: Excessive sweating during sleep, especially at night, can be a sign of an underlying inflammatory process, which can be present in primary myelofibrosis (PMF).

- Unexplained weight loss: This can occur due to various reasons in primary myelofibrosis (PMF), including decreased appetite, increased metabolic rate due to inflammation, and difficulty absorbing nutrients.

This image illustrates several key signs and symptoms associated with primary myelofibrosis (PMF). Anemia, characterized by a decrease in red blood cells, can lead to fatigue, weakness, and shortness of breath. Massive hepatosplenomegaly refers to a significant enlargement of both the liver (hepatomegaly) and spleen (splenomegaly), which can cause discomfort, early satiety (feeling full after eating a small amount), and other complications. Additionally, hypermetabolism (increased metabolic rate) can manifest as unintended weight loss, night sweats, and fatigue, potentially contributing to a reduced quality of life in individuals with PMF.

Later Myelofibrosis Symptoms

- Enlarged spleen (splenomegaly): This is a hallmark primary myelofibrosis (PMF) symptom and can be felt as a mass or fullness in the upper left abdominal region. The enlarged spleen can cause discomfort, early satiety (feeling full after eating a small amount), and other myelofibrosis symptoms.

- Bone pain: This can be a general ache or a sharp pain in the bones, often occurring in the back, legs, or ribs.

- Easy bruising or bleeding: This is due to a decrease in the number of platelets, which are essential for blood clotting.

- Myelofibrosis symptoms related to low blood cell counts:

- Anemia: This deficiency in red blood cells can lead to symptoms like pale skin, shortness of breath, and dizziness.

- Frequent infections: A decrease in white blood cells can weaken the immune system, making individuals more susceptible to infection

Complications of PMF

Primary myelofibrosis (PMF) can lead to various complications if left untreated or if the treatment is not effective.

Infection

Due to a weakened immune system caused by decreased white blood cell counts, individuals with primary myelofibrosis (PMF) are more susceptible to infections, including bacterial, viral, and fungal infections. These infections can be serious and require prompt medical attention.

Transformation to Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML)

In some cases, primary myelofibrosis (PMF) can transform into AML, a more aggressive form of leukemia. This occurs due to the accumulation of additional genetic mutations in the bone marrow cells over time. The risk of transformation increases with the duration and severity of primary myelofibrosis (PMF).

Bleeding and Thrombosis

Primary myelofibrosis (PMF) can lead to both bleeding and thrombosis (blood clot formation) due to imbalances in blood cell production.

- Bleeding: A decrease in platelets can increase the risk of easy bruising, bleeding from the gums or nose, and internal bleeding.

- Thrombosis: Although less common than bleeding, blood clots can form in various locations, such as the deep veins of the legs (deep vein thrombosis) or the lungs (pulmonary embolism). These clots can be life-threatening and require immediate medical attention.

Portal Hypertension

An enlarged spleen (splenomegaly) can block the flow of blood through the portal vein, a major vein in the abdomen. This can lead to portal hypertension, a condition characterized by high blood pressure in the portal vein system. Myelofibrosis symptoms may include abdominal discomfort, ascites (fluid accumulation in the abdomen), and variceal bleeding (bleeding from enlarged veins in the esophagus or stomach).

Extramedullary hematopoiesis

In some cases, the bone marrow becomes so severely affected by fibrosis that it cannot produce enough blood cells. As a compensatory mechanism, blood cell production can start occurring outside the bone marrow, in organs like the liver and spleen. This is called extramedullary hematopoiesis. While it helps to maintain blood cell counts to some extent, it can also lead to organ dysfunction if not properly controlled.

Other complications

- Bone pain: The bone marrow fibrosis can cause chronic pain in the bones.

- Fatigue: This remains a significant issue even with treatment, impacting quality of life.

- Splenomegaly-related symptoms: The enlarged spleen can cause discomfort, early satiety, and other bothersome symptoms.

Laboratory Investigations and Diagnostic Criteria for PMF

Diagnosing primary myelofibrosis (PMF) involves a multi-step approach combining various laboratory investigations and clinical criteria.

Laboratory Investigations

- Complete blood count (CBC): This basic blood test can reveal:

- Early stage: Anemia, leukocytosis, thrombocytosis

- Late stage: Anemia, leukopenia and thrombocytopenia (although not always present in PMF).

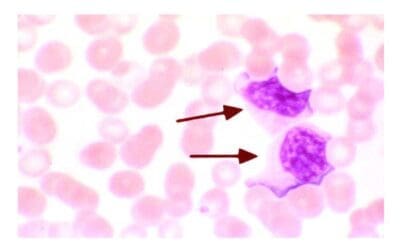

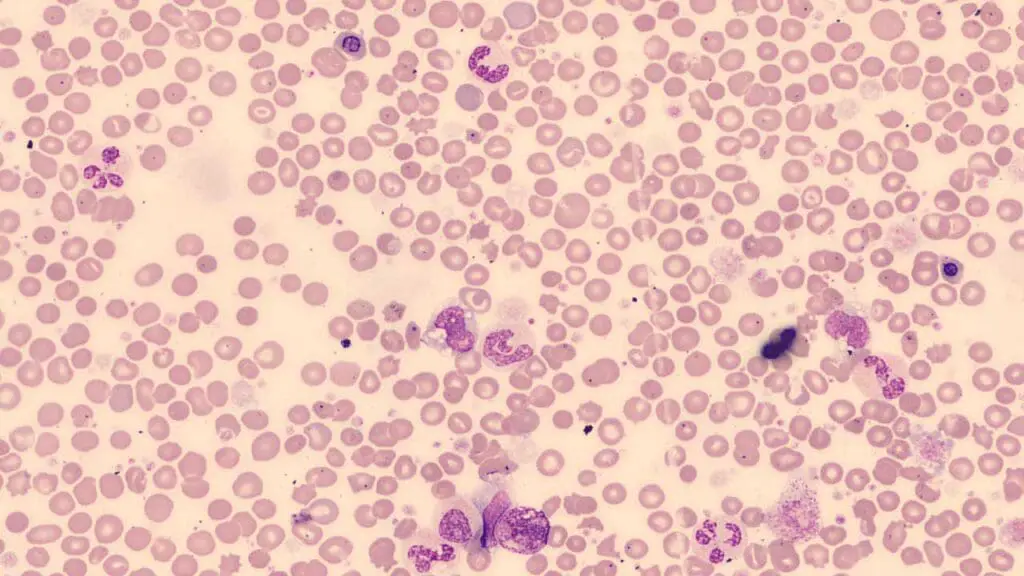

- Peripheral blood smear: Leukoerythroblastic picture with tear-drop red cells.

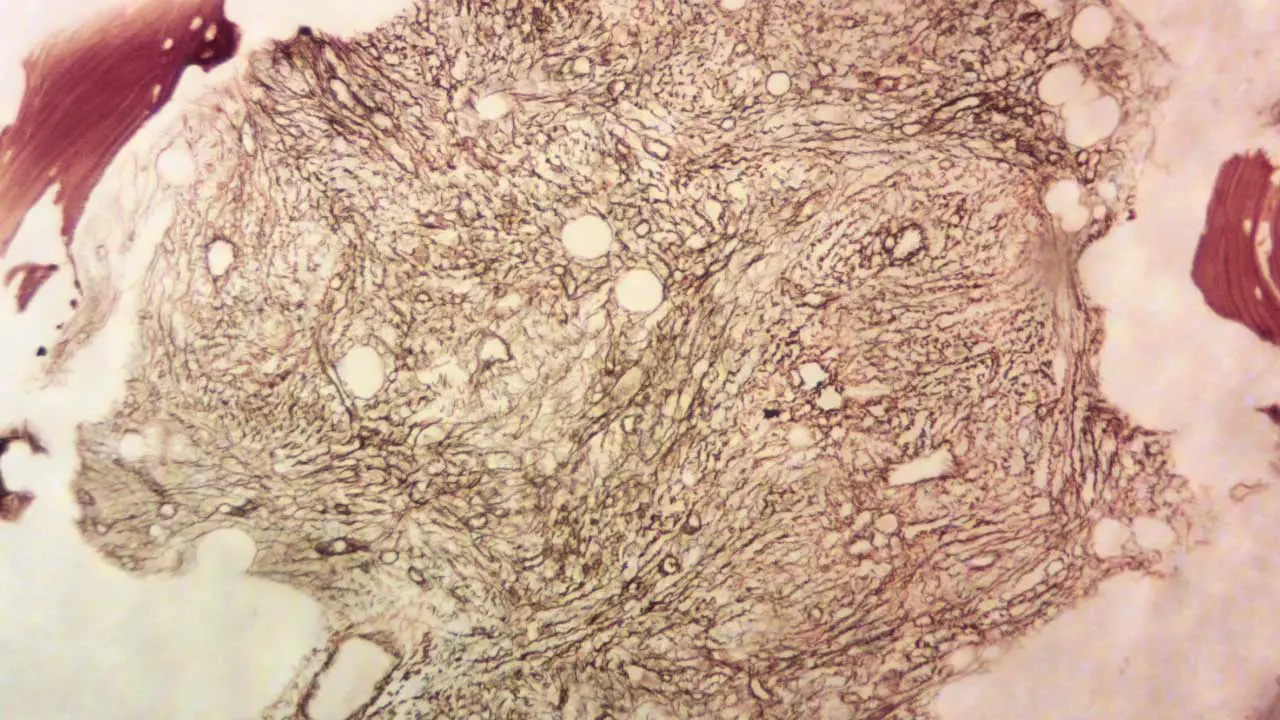

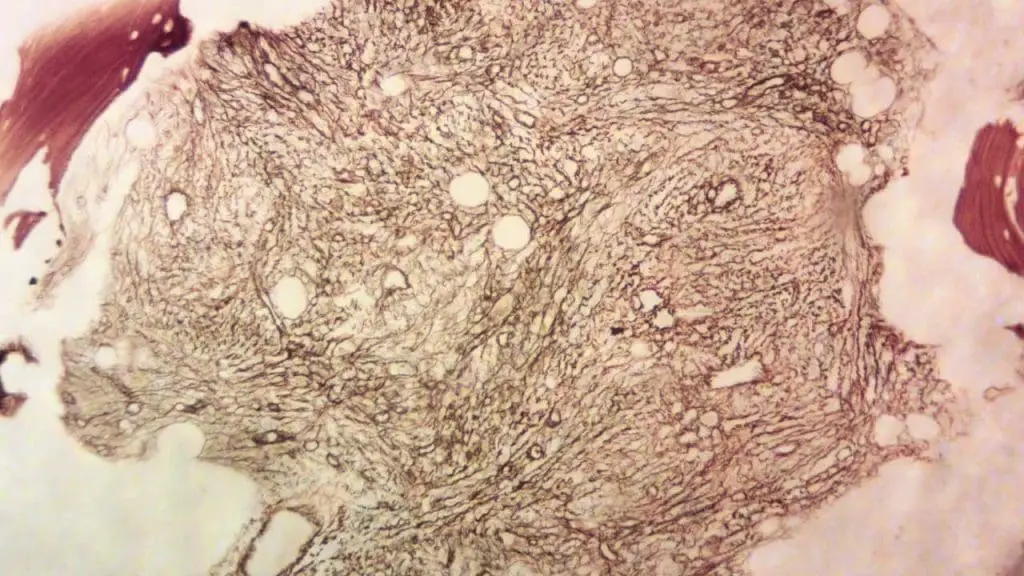

- Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy: Fibrotic hypercellular marrow with increased megakaryocytes

- Molecular testing: This tests for specific gene mutations, such as JAK2, CALR, and MPL, in the bone marrow cells. These mutations are highly suggestive of primary myelofibrosis (PMF) but not diagnostic in isolation.

Bone Marrow Grading in PMF

Grading systems are used to assess the severity of bone marrow fibrosis, a crucial feature of the disease. These grading systems provide additional information about the extent of fibrosis, which can influence prognosis and treatment decisions.

1. European Consensus Grading System

- Grade 0: No reticulin fibers (protein involved in scar formation) visible in the bone marrow.

- Grade 1: Early reticulin sclerosis (fibrosis) with minimal collagen deposition.

- Grade 2: Advanced reticulin sclerosis with more extensive collagen deposition but still maintaining some normal bone marrow architecture.

- Grade 3: Advanced collagen fibrosis with complete loss of normal bone marrow architecture.

2. WHO Grading System

- This system is similar to the European Consensus system but uses slightly different terminology:

- Grade 0: No reticulin fibrosis.

- Grade 1: Minimal reticulin fibrosis.

- Grade 2: Moderate reticulin fibrosis.

- Grade 3: Severe reticulin fibrosis.

Relationship with Prognosis

- Higher fibrosis grades (2 or 3) generally indicate a worse prognosis compared to lower grades (0 or 1) due to reduced ability of the bone marrow to produce healthy blood cells and increased risk of complications.

- However, other factors like age, presence of specific mutations (JAK2, CALR, MPL), and overall health also play a significant role in determining the individual’s prognosis.

Importance of Grading

- Helps refine diagnosis: Differentiating pre-PMF (MF-0 or MF-1) from overt PMF (MF-2 or MF-3) based on fibrosis grade.

- Provides additional information for risk stratification beyond solely relying on prognostic scoring systems like DIPSS Plus.

- Informs treatment decisions: May influence the choice of therapy or the need for more aggressive management approaches.

Limitations of Grading

- Grading systems are based on microscopic evaluation of bone marrow biopsies, which can be subjective and prone to variability between different observers.

- The presence of fibrosis alone doesn’t fully capture the complexity of PMF, and other factors need to be considered when making treatment decisions.

Diagnostic Criteria

The International Working Group for Myeloproliferative Neoplasms (IWG-MPN) established diagnostic criteria for PMF.

Early/ prefibrotic stage

Major criteria

- Megakaryocytic proliferation and atypia in BM biopsy, Grade <2 BM fibrosis, increased BM cellularity (age adjusted) with granulocytic proliferation and decreased erythropoiesis (often)

- JAK2, CALR, or MPL mutation or presence of another clonal marker or absence of reactive BM reticulin fibrosis

- Diagnostic criteria for BCR-ABL1-positive CML, PV, ET, MDS or other myeloid neoplasms are not met

Minor criteria

- Anemia not due to a comorbid condition

- Leukocytosis ≥ 11 x 109/L

- Palpable splenomegaly

- Increased LDH level

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of primary myelofibrosis (PMF) requires meeting all major criteria and at least one minor criterion.

Overt fibrotic stage

Major criteria

- Megakaryocytic proliferation and atypia in BM biopsy with reticulin and / or Grade 2 or 3 collagen fibrosis

- JAK2, CALR, or MPL mutation or presence of another clonal marker or absence of reactive MF

- Diagnostic criteria for BCR-ABL1-positive CML, PV, ET, MDS or other myeloid neoplasms are not met

Minor criteria

- Anemia not due to a comorbid condition

- Leukocytosis ≥ 11 x 109/L

- Palpable splenomegaly

- Increased LDH level

- Leukoerythroblastosis

Diagnosis

A diagnosis requires meeting all major criteria and 1 or more minor criterion confirmed in 2 consecutive determinations

Treatment and Management of PMF

While there is currently no cure for primary myelofibrosis (PMF), several treatment options are available to manage the symptoms, improve quality of life, and potentially slow disease progression.

Treatment

Treatment decisions in primary myelofibrosis (PMF) are individualized based on several factors, including symptom severity, age, risk category, and mutational status.

- Low-risk PMF

- Watchful waiting: For patients with minimal myelofibrosis symptoms, a “watch-and-wait” approach may be adopted. This involves regular monitoring but delaying active treatment.

- Targeted myelofibrosis symptom management: Medications may be used to manage specific symptoms like fatigue or itching.

- Intermediate- and high-risk PMF

- JAK inhibitors: These drugs, such as ruxolitinib (Jakafi) or fedratinib (Inrebic), target the JAK-STAT pathway, reducing inflammation and splenomegaly, and improving symptoms significantly.

- Other targeted therapies: Based on specific mutations, other targeted therapies may be used alone or in combination with JAK inhibitors (e.g., drugs targeting certain signaling pathways).

- Splenectomy: In select cases, surgical removal of the spleen may be considered for patients with severe splenomegaly causing significant discomfort or pain.

- Low-dose radiation: Can be used for localized extramedullary hematopoiesis (blood cell production outside the bone marrow) that’s causing discomfort.

- Clinical trials: Patients may be eligible for clinical trials investigating new and emerging therapies for PMF.

- Stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT): This is the only potentially curative treatment option for PMF but carries significant risks of serious complications. It’s typically considered for younger, healthier patients with intermediate or high-risk disease who have a suitable donor.

Other important treatment considerations

- Low-dose aspirin: May be used in some patients to reduce the risk of blood clots (thrombosis), especially those with high platelet counts.

- Blood transfusions: Used to manage anemia-related symptoms.

- Antibiotics or antifungals: For the treatment or prevention of infections.

- Androgens: Can be used for anemia but have side effects and are rarely used today.

Prognosis

The prognosis of primary myelofibrosis (PMF) is highly variable and depends on various risk factors:

- Age: Younger patients have a better outlook.

- Molecular mutations: CALR mutations are generally associated with a better prognosis compared to JAK2 or MPL.

- Blood counts: Severe anemia and abnormal platelet counts indicate a higher-risk disease.

- Symptoms: The presence and severity of constitutional symptoms can affect prognosis.

There are several scoring systems like the DIPSS-plus, which healthcare professionals use to determine the risk category of a patient with PMF:

- Low risk: Median survival of >15 years

- Intermediate-1: Median survival around 7 years

- Intermediate-2: Median survival around 4 years

- High risk: Median survival of approximately 2 years

Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System (DIPSS) Plus for PMF

The DIPSS Plus is a prognostic scoring system used to assess the survival and risk of transformation to acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in patients with primary myelofibrosis (PMF). It incorporates factors beyond the original DIPSS system, providing a more accurate and comprehensive risk stratification.

DIPSS Plus Score

The score is calculated by summing the points assigned to each of the following six factors:

| Factor | Description | Points |

| Age | > 65 years | 1 |

| Hemoglobin | < 10 g/dL | 2 |

| Leukocytes | > 25 x 10^9/L | 1 |

| Circulating blasts | ≥ 1% | 1 |

| Platelets | < 100 x 10^9/L | 1 |

| Presence of specific gene mutations | JAK2 V617F mutation or high-risk CALR mutation | 1 |

Risk Stratification

Based on the total score, patients are classified into different risk groups:

| Total Score | Risk Group | Median Survival (years) | Risk of AML Transformation (%) |

| 0-1 | Low | >10 | <5 |

| 2 | Intermediate-1 | 7 | 5-10 |

| 3 | Intermediate-2 | 4.5 | 10-15 |

| ≥ 4 | High | 1.5 | >15 |

Advantages of DIPSS Plus

- Improved accuracy: DIPSS Plus provides a more refined risk stratification compared to the original DIPSS system.

- Incorporation of mutations: It takes into account the presence of specific gene mutations, which are crucial prognostic factors in primary myelofibrosis (PMF).

- Simple and easy to use: The scoring system is straightforward and easily calculable by healthcare professionals.

Limitations of DIPSS Plus

- Doesn’t predict response to specific therapies: The DIPSS Plus score does not directly predict how a patient will respond to different treatment options.

- Prognostic tool, not a definitive predictor: The score provides an estimate of risk and should not be interpreted as a definitive predictor of individual outcomes.

Post-essential thrombocythemia (ET) MF and post-polycythemia vera (PV) MF

Post-ET MF

- This occurs when a patient diagnosed with essential thrombocythemia (ET), characterized by an increased platelet count, eventually progresses to develop myelofibrosis.

- This transition can happen years after the initial diagnosis of ET, with an average time of 7-20 years.

- The overall risk of developing post-ET MF is around 1.6-9%.

Post-PV MF

- This occurs when a patient diagnosed with polycythemia vera (PV), characterized by an increased red blood cell count, progresses to develop myelofibrosis.

- Similar to post-ET MF, this transformation can take years to occur, with an average of 7-20 years after the initial PV diagnosis.

- The risk of developing post-PV MF is slightly higher compared to post-ET MF, with an estimated range of 5-14%.

It’s important to note that both post-ET MF and post-PV MF are classified as primary myelofibrosis (PMF).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Is primary myelofibrosis curable?

No, primary myelofibrosis (PMF) is generally not considered curable with currently available treatment options. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation (SCT) offers the only potential for cure in PMF. This procedure replaces the patient’s bone marrow with healthy stem cells from a donor but it’s a high-risk procedure typically reserved for younger patients with high-risk disease and a suitable donor.

What are the 4 hallmarks of myelofibrosis?

The four hallmarks of myelofibrosis are:

- Enlarged spleen (splenomegaly): This is a characteristic feature of primary myelofibrosis (PMF) and can be felt as a mass or fullness in the upper left abdominal region. The enlarged spleen can cause various symptoms, including:

- Early satiety (feeling full after eating a small amount)

- Discomfort in the upper left abdomen

- Shortness of breath in severe cases

- Anemia: This occurs due to a decrease in red blood cell production in the bone marrow. Symptoms of anemia can include:

- Fatigue

- Weakness

- Pale skin

- Shortness of breath

- Dizziness

- Bone marrow fibrosis: This is a hallmark feature of primary myelofibrosis (PMF) and refers to the scarring and hardening of the bone marrow. This scarring disrupts the normal architecture of the bone marrow, making it difficult for healthy blood cells to be produced.

- Debilitating disease-associated myelofibrosis symptoms: These myelofibrosis symptoms can significantly impact a patient’s quality of life and include:

- Fatigue: This is a common and often the first noticeable myelofibrosis symptom. It can be described as a feeling of tiredness, exhaustion, and lack of energy that persists even after adequate rest.

- Night sweats: These are excessive sweating episodes that occur during sleep and can be related to the body’s attempt to regulate temperature due to inflammation.

- Unexplained weight loss: This can occur due to various reasons in primary myelofibrosis (PMF), including decreased appetite, increased metabolic rate due to inflammation, and difficulty absorbing nutrients.

- Bone pain: This can be a general ache or a sharp pain in the bones, often occurring in the back, legs, or ribs.

- Easy bruising or bleeding: This is due to a decrease in the number of platelets, which are essential for blood clotting.

What are the signs myelofibrosis is getting worse?

While the course of myelofibrosis (MF) can vary considerably from person to person, there are signs and symptoms that might indicate the disease is worsening:

Progression of Existing Myelofibrosis Symptoms

- Increased fatigue and weakness: This is a common myelofibrosis symptom, but if it worsens significantly and interferes significantly with daily activities, it could suggest disease progression.

- ** Worsening pain:** Bone pain, often in the back, legs, or ribs, can worsen as the disease progresses.

- More pronounced weight loss: Unexplained weight loss can occur in myelofibrosis and may become more noticeable as the disease worsens.

- Splenomegaly progression: An enlarged spleen (splenomegaly) is a hallmark of myelofibrosis. If the spleen continues to grow significantly, it can cause discomfort, early satiety (feeling full after eating a small amount), and other myelofibrosis symptoms.

Development of New Myelofibrosis Symptoms

- Fevers and night sweats: These can be signs of increased inflammation or potential infections, which are more common with advanced myelofibrosis.

- Increased bleeding or bruising: This can occur due to a decrease in platelets, which are essential for blood clotting.

- Shortness of breath: This can be caused by various factors in myelofibrosis, including anemia (low red blood cell count) or enlarged spleen compressing the lungs.

- Frequent infections: A weakened immune system due to myelofibrosis can increase susceptibility to infections.

Changes in Blood Tests

- Decreasing blood counts: Lower red blood cell (anemia), white blood cell, and platelet counts may be observed as the disease progresses.

- Increased blast count: A rise in the number of immature blood cells (blasts) in the bone marrow can indicate a more aggressive form of myelofibrosis or potential transformation to acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

How painful is myelofibrosis?

The pain experienced with myelofibrosis (MF) can vary considerably from person to person, ranging from no pain to significant and debilitating pain. Several factors contribute to this variability.

Causes of Pain in Myelofibrosis

- Bone marrow fibrosis: The hallmark feature of myelofibrosis involves scarring and hardening of the bone marrow. This process can irritate and inflame surrounding tissues, leading to pain, especially in the back, ribs, and legs.

- Splenomegaly: An enlarged spleen, a common feature of myelofibrosis, can press on nearby organs like the stomach and diaphragm, causing discomfort and pain in the upper left abdomen.

- Increased inflammation: Chronic inflammation associated with myelofibrosis can contribute to generalized aches and pains throughout the body.

- Individual pain tolerance: People have varying levels of pain tolerance, which influences how they perceive and experience pain.

Severity of Pain

- Mild pain: Some individuals with myelofibrosis experience mild, occasional aches that might not significantly interfere with daily activities.

- Moderate pain: This is more common and can be managed with medications like pain relievers and anti-inflammatory drugs.

- Severe pain: In some cases, the pain can be severe and debilitating, requiring additional pain management strategies like nerve blocks or stronger pain medications.

Management of Pain in Myelofibrosis

- Identifying the cause: Accurately determining the source of the pain is crucial for effective management.

- Medications: Pain relievers like nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and stronger pain medications like opioids may be prescribed depending on the severity of pain.

- Other strategies: Other approaches like physical therapy, massage therapy, and relaxation techniques can help manage pain and improve overall well-being.

- Addressing the underlying cause: When possible, addressing the underlying cause of the pain, such as managing inflammation and reducing spleen size, can significantly improve pain levels.

What causes death with myelofibrosis?

Myelofibrosis (MF) can lead to death due to a variety of causes.

- Transformation to Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML)

One of the most significant risks for patients with MF is the progression of the disease to acute myeloid leukemia (AML). AML is an aggressive form of blood cancer that can be rapidly fatal if not treated promptly. The risk of AML transformation varies, but it’s a significant contributor to death in myelofibrosis patients.

- Complications of Bone Marrow Failure

As MF progresses, the bone marrow becomes increasingly scarred and fibrotic. This can severely impair its ability to produce healthy blood cells, leading to complications such as:

- Severe anemia: This can cause life-threatening fatigue, weakness, and shortness of breath.

- Infections: A weakened immune system due to bone marrow failure increases vulnerability to severe infections that can be difficult to treat.

- Bleeding: Low platelet counts can cause spontaneous bleeding, which can be life-threatening in some cases.

- Complications of Splenomegaly

An enlarged spleen (splenomegaly), a common feature of myelofibrosis, can lead to various complications:

- Splenic rupture: In rare cases, a severely enlarged spleen can rupture, causing massive internal bleeding and potentially leading to death.

- Portal hypertension: Increased pressure in the blood vessels around the liver due to splenomegaly can lead to portal hypertension, resulting in bleeding and other complications.

- Other Causes

- Heart failure: Complications like heart failure can occur due to chronic anemia, iron overload from transfusions, or other underlying medical problems.

- Liver failure: Advanced myelofibrosis, portal hypertension, and certain complications can lead to liver failure.

- Thrombosis (blood clots): Patients with myelofibrosis might have an increased risk of blood clots, which can cause serious complications like stroke or heart attack.

- Comorbidities

Myelofibrosis mainly affects older individuals who often have other existing medical conditions (comorbidities). These conditions, along with complications of myelofibrosis, can contribute to death.

What organs does myelofibrosis affect?

While myelofibrosis (MF) primarily affects the bone marrow, it can indirectly impact various organs due to its influence on blood cell production and the presence of specific myelofibrosis symptoms.

1. Spleen

Splenomegaly (enlarged spleen): This is a hallmark feature of myelofibrosis. The spleen filters blood cells, removing old or damaged ones. An enlarged spleen can occur due to increased workload in trying to compensate for abnormal blood cell production and removal of abnormal cells. This can cause:

- Discomfort or pain in the upper left abdomen

- Early satiety (feeling full after eating a small amount)

- Pressure on nearby organs like the stomach and diaphragm

2. Liver

Portal hypertension: When the enlarged spleen disrupts blood flow in the portal vein (drains blood from the spleen and intestines to the liver), it can lead to increased pressure in the portal vein system. This, in turn, can cause:

- Variceal bleeding: Increased pressure can cause enlarged veins in the esophagus or stomach to rupture, leading to potentially life-threatening bleeding.

- Ascites: Accumulation of fluid in the abdomen.

3. Lungs

Extramedullary hematopoiesis (EMH): In rare cases, blood cell production can occur outside the bone marrow, including in the lungs. This can cause:

- Coughing

- Shortness of breath

- Chest pain

4. Skin

Pruritus (itching): This can be a common symptom in myelofibrosis, although the exact cause is not fully understood.

5. Other organs

- Bones: Bone pain can be a common symptom in myelofibrosis due to the abnormal bone marrow environment and inflammation.

- Heart: Chronic anemia and other factors associated with myelofibrosis can potentially increase the risk of heart failure.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- https://mpn-hub.com/medical-information/international-consensus-classification-2022-for-myeloproliferative-neoplasms

- Gianelli U, Thiele J, Orazi A, Gangat N, Vannucchi AM, Tefferi A, Kvasnicka HM. International Consensus Classification of myeloid and lymphoid neoplasms: myeloproliferative neoplasms. Virchows Arch. 2023 Jan;482(1):53-68. doi: 10.1007/s00428-022-03480-8. Epub 2022 Dec 29. PMID: 36580136; PMCID: PMC9852206.

- Goldberg S, Hoffman J. Clinical Hematology Made Ridiculously Simple, 1st Edition: An Incredibly Easy Way to Learn for Medical, Nursing, PA Students, and General Practitioners (MedMaster Medical Books). 2021.

- Keohane EM, Otto CN, Walenga JM. Rodak’s Hematology 6th Edition (Saunders). 2019.

- Takenaka K, Shimoda K, Akashi K. Recent advances in the diagnosis and management of primary myelofibrosis. Korean J Intern Med. 2018 Jul;33(4):679-690. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2018.033. Epub 2018 Apr 20. PMID: 29665657; PMCID: PMC6030412.

- Oon, S.F., Singh, D., Tan, T.H. et al. Primary myelofibrosis: spectrum of imaging features and disease-related complications. Insights Imaging 10, 71 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13244-019-0758-y

- Tefferi A. Primary myelofibrosis: 2023 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management . American Journal of Hematology; 2023;98(5):801-821.

- Verstovsek, S., Mesa, R.A., Livingston, R.A. et al. Ten years of treatment with ruxolitinib for myelofibrosis: a review of safety. J Hematol Oncol 16, 82 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-023-01471-z