TL;DR

Neutrophilia (high neutrophils) is an elevated neutrophil count, crucial for infection defense. Absolute neutrophilia on the other hand is a condition characterized by an abnormally high number of neutrophils indicating a heightened immune response or other underlying medical condition.

- Causes ▾: Infections, inflammation, stress, medications, and hematologic disorders.

- Symptoms ▾: Vary by cause, from fever to none.

- Diagnosis ▾: CBC, differential, blood smear, and potentially imaging/biopsy.

- Treatment ▾: Targets the underlying cause (antibiotics, anti-inflammatories), with supportive care.

- Complications ▾: Prolonged/severe cases risk organ damage and hyperviscosity.

*Click ▾ for more information

Introduction

Neutrophilia is a condition characterized by an abnormally high neutrophils count in the circulating blood. Neutrophils are the most abundant type of white blood cell and are a crucial component of the innate immune system, primarily responsible for defending the body against bacterial infections and other forms of acute inflammation. It’s important to distinguish between relative and absolute neutrophilia (high neutrophils).

Clinical Significance and Relevance

Neutrophilia (high neutrophils) is a common finding in clinical practice and serves as an indicator of various underlying physiological and pathological processes. Its clinical significance lies in its ability to:

- Signal infection: It is a primary indicator of acute bacterial infections. It can help clinicians assess the severity of an infection.

- Reflect inflammation: It can be associated with inflammatory conditions, such as appendicitis, pancreatitis, and autoimmune diseases.

- Indicate stress: Physiological stress (e.g., trauma, surgery) and emotional stress can trigger neutrophilia (high neutrophils).

- Point to hematological disorders: In some cases, it can be a sign of underlying hematologic malignancies, such as chronic myeloid leukemia.

- Guide diagnostic and therapeutic decisions: The presence of neutrophilia (high neutrophils) prompts further investigation to determine the underlying cause, which in turn guides appropriate treatment strategies.

Therefore, understanding neutrophilia (high neutrophils) is essential for clinicians to accurately interpret laboratory findings, diagnose underlying conditions, and provide timely and effective patient care.

Overview of White Blood Cell (WBC) Count

The WBC count measures the total number of white blood cells in a specific volume of blood. White blood cells, or leukocytes, are crucial components of the immune system, defending the body against infections and other diseases. Changes in the WBC count can indicate various health conditions, from infections to immune disorders.

Complete Blood Count (CBC) and Differential Count

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): The CBC is a common blood test that provides a comprehensive overview of blood cell counts, including red blood cells (RBCs), white blood cells (WBCs), and platelets. It measures the total number of WBCs, RBCs, hemoglobin, hematocrit, and platelet count. The CBC is a fundamental diagnostic tool used to assess overall health and detect various conditions.

- Differential Count: The differential count is a component of the CBC that provides a breakdown of the different types of WBCs present in the blood. It determines the percentage of each type of WBC:

- Significance: The differential count is crucial for identifying specific types of infections, inflammatory conditions, and hematologic disorders. For example, an elevated neutrophil count often indicates a bacterial infection, while an increased lymphocyte count may suggest a viral infection.

Normal Ranges for WBCs

- Total WBC Count: 4,500 to 11,000 cells/µL (or 4.5 to 11 x 109 cells/L)

- Differential Count:

- Neutrophils: 2,500 to 7,000 cells/µL (or 40% to 60% of total WBCs)

- Lymphocytes: 1,000 to 4,000 cells/µL (or 20% to 40% of total WBCs)

- Monocytes: 200 to 800 cells/µL (or 2% to 8% of total WBCs)

- Eosinophils: 100 to 500 cells/µL (or 1% to 4% of total WBCs)

- Basophils: 25 to 100 cells/µL (or 0.5% to 1% of total WBCs)

It’s important to note that these ranges can be influenced by factors such as age, sex, and overall health.

Absolute Neutrophilia vs. Relative Neutrophilia

Absolute Neutrophilia (High Neutrophils)

First of all, what does absolute neutrophils mean?

“Absolute neutrophils” refers to the actual number of neutrophils present in a specific volume of blood, typically measured as cells per microliter (cells/µL). It’s a precise count, not a percentage.

What if the absolute neutrophil count is high?

A high absolute neutrophil count (ANC) is also known as absolute neutrophilia (high neutrophils).

Absolute neutrophilia (high neutrophils) is an actual increase in the number of neutrophils in the circulating blood, quantified by the absolute neutrophil count (ANC). This means there’s a true expansion of the neutrophil population leading to absolute neutrophilia. Absolute neutrophilia (high neutrophils) production or release often signifies an active immune response.

It is determined by calculating the ANC, which is the total WBC count multiplied by the percentage of neutrophils (segmented neutrophils + bands) in the differential count.

Common Causes

- Bacterial infections (e.g., pneumonia, abscesses)

- Inflammatory conditions (e.g., appendicitis, inflammatory bowel disease)

- Myeloproliferative disorders (e.g., chronic myeloid leukemia)

- Tissue necrosis (e.g., myocardial infarction)

- Certain medications (e.g., corticosteroids)

- Stress (physical or emotional)

Relative Neutrophilia

An apparent increase in the percentage of neutrophils in the differential count, but the absolute number of neutrophils may be within the normal range or only slightly elevated. This is due to a decrease in plasma volume, leading to hemoconcentration. It reflects a concentration of blood components rather than a true increase in neutrophil production (absolute neutrophilia). It may not indicate an active infection or inflammation.

It is assessed by the percentage of neutrophils in the differential count. The ANC may be normal or slightly elevated.

Common Causes

- Dehydration

- Severe vomiting or diarrhea

- Burns

- Stress

Differentiation and Clinical Implications

The primary difference lies in the absolute number of neutrophils. Absolute neutrophilia (high neutrophils) involves a genuine increase, while relative neutrophilia is a result of hemoconcentration.

The ANC is the most important measurement to differentiate between the two.

Clinical Implications

- Absolute Neutrophilia: Absolute neutrophilia (high neutrophils) requires thorough investigation to identify the underlying cause, as it often indicates a significant pathological process. Treatment of absolute neutrophilia (high neutrophils) focuses on addressing the root cause, such as antibiotics for bacterial infections or anti-inflammatory medications for inflammatory conditions.

- Relative Neutrophilia: Relative neutrophilia requires assessment of the patient’s hydration status. Treatment focuses on restoring fluid balance, such as intravenous fluids for dehydration. Failing to correctly identify relative neutrophilia, may lead to unnecessary testing and treatment.

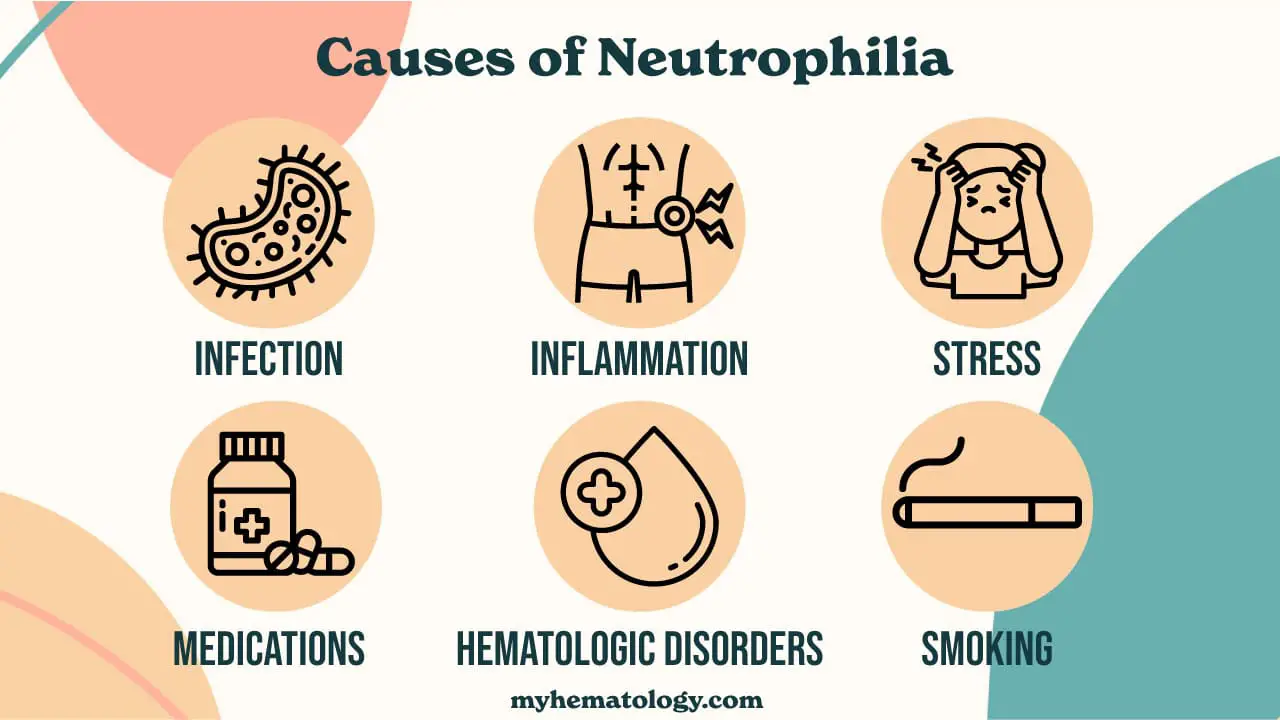

What is the cause of neutrophilia (high neutrophils)?

Infections

- Bacterial infections (most common)

- Pneumonia

- Abscesses

- Sepsis

- Urinary tract infections

- Skin infections

- Less common infections

- Fungal infections

- Parasitic infections

Inflammation

- Acute inflammatory conditions

- Appendicitis

- Pancreatitis

- Cholecystitis

- Vasculitis

- Chronic inflammatory conditions

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis)

Stress

- Physical stress

- Trauma

- Surgery

- Burns

- Extreme exercise

- Psychological stress

Medications

- Corticosteroids

- Lithium

- Growth factors (e.g., granulocyte colony-stimulating factor [G-CSF])

Hematologic Disorders

- Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML)

- Polycythemia vera

- Essential thrombocythemia

- Other myeloproliferative neoplasms

Other Causes

- Smoking

- Malignancy (non-hematologic)

- Lung cancer

- Other solid tumors

- Tissue necrosis

- Myocardial infarction

- Post-splenectomy

- Metabolic disorders

- Diabetic ketoacidosis

- Acute hemorrhage

What happens if neutrophils are high? Common Signs and Symptoms of Neutrophilia

The clinical presentation and symptoms associated with neutrophilia (high neutrophils) are highly variable and depend largely on the underlying cause. Neutrophilia (high neutrophils) itself doesn’t typically cause specific symptoms, but rather reflects an underlying condition.

Symptoms Related to Infections

- Fever and chills: These are common signs of infection, particularly bacterial infections.

- Localized pain and swelling: Depending on the site of infection (e.g., pneumonia, abscess), patients may experience pain, tenderness, and swelling.

- Purulent discharge: In skin or wound infections, pus may be present.

- Cough and shortness of breath: Associated with pneumonia or other respiratory infections.

- Dysuria and frequency: Suggestive of urinary tract infections.

- Systemic symptoms: Fatigue, malaise, and loss of appetite can occur with severe infections.

Symptoms Related to Inflammation

- Pain and swelling: In inflammatory conditions like appendicitis or arthritis, patients may experience localized pain, swelling, and redness.

- Abdominal pain: Associated with appendicitis, pancreatitis, or inflammatory bowel disease.

- Joint pain and stiffness: In rheumatoid arthritis or other inflammatory joint conditions.

- Skin rashes or lesions: Associated with certain inflammatory conditions.

Symptoms Related to Stress

These symptoms are often transient and resolve once the stressor is removed.

- Tachycardia

- Increased blood pressure

- Anxiety and restlessness

Symptoms Related to Hematologic Disorders

- Fatigue and weakness: Common in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and other myeloproliferative neoplasms.

- Night sweats

- Weight loss

- Splenomegaly: Enlarged spleen, which can cause abdominal discomfort.

- Easy bruising or bleeding

Symptoms Related to Other Causes

- Chest pain: Associated with myocardial infarction.

- Shortness of breath: Can be related to lung cancer or other malignancies.

- Symptoms related to the underlying malignancy: weight loss, pain, etc.

Asymptomatic Neutrophilia

In some cases, neutrophilia (high neutrophils) may be discovered incidentally during routine blood work. This is more common in mild cases or in chronic conditions.

Physical Examination Findings

- Fever

- Tachycardia

- Localized warmth, redness, and swelling

- Lymphadenopathy

- Splenomegaly

- Signs of dehydration: Dry mucous membranes, decreased skin turgor.

Laboratory Investigations for Neutrophilia (High Neutrophils)

Laboratory investigations for absolute neutrophilia (high neutrophils) focus on confirming the elevated neutrophil count, identifying the underlying cause, and assessing the severity of the condition.

Complete Blood Count (CBC) with Differential

This is the cornerstone of the investigation. It provides the total white blood cell (WBC) count and a breakdown of the different types of WBCs (differential count). Crucially, it provides the data necessary to calculate the Absolute Neutrophil Count (ANC).

Absolute Neutrophil Count (ANC) Calculation

The ANC is a more accurate measure of the number of neutrophils than the percentage alone. The Absolute Neutrophil Count (ANC) provides the actual number of neutrophils in the blood. This is vital for distinguishing between absolute neutrophilia (high neutrophils) and relative neutrophilia. The ANC offers a more accurate assessment of the body’s ability to combat infection and helps diagnose the true underlying cause of an abnormal neutrophil count, guiding appropriate clinical management.

The ANC is calculated by multiplying the total WBC count by the percentage of neutrophils (segmented neutrophils + band neutrophils) in the differential count.

Formula: ANC = Total WBC count x (% segmented neutrophils + % band neutrophils)

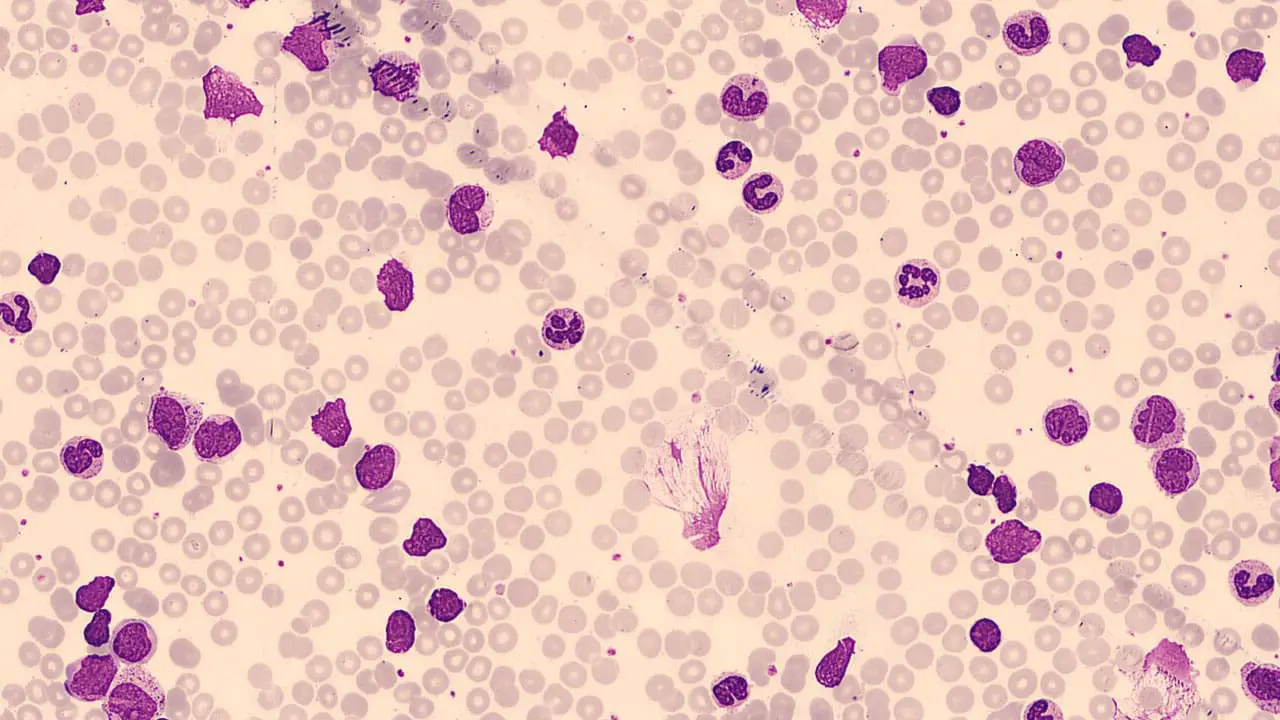

Blood Smear (Peripheral Blood Smear)

We use the peripheral blood smear to visually examine the morphology of neutrophils and other blood cells. We will be able to identify immature neutrophils (band cells, metamyelocytes, myelocytes), which indicate a “left shift” and suggest an active infection or bone marrow stimulation.

Peripheral blood smears also allow the detection of any abnormal white blood cells, such as blasts (immature cells) in leukemia and to evaluate for toxic granulation, Dohle bodies, or vacuolization in neutrophils, which are morphological changes that are seen with infection and inflammation.

Inflammatory Markers

- C-Reactive Protein (CRP): A sensitive marker of inflammation. Elevated CRP levels indicate the presence of inflammation, but they do not specify the cause.

- Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR): Another marker of inflammation. It is less specific than CRP but can be useful in monitoring chronic inflammatory conditions.

- Procalcitonin: This is a biomarker that is more specific for bacterial infections. It can be useful to help differentiate a bacterial infection from a viral infection or other inflammatory process.

Microbiological Tests

- Blood Cultures: To identify bacteria or fungi in the bloodstream, especially in cases of suspected sepsis.

- Urine Cultures: To detect urinary tract infections.

- Sputum Cultures: To identify respiratory pathogens in cases of pneumonia.

- Wound Cultures: To identify the pathogens causing wound infections.

- Other cultures as clinically indicated.

Imaging Studies

- Chest X-ray: To evaluate for pneumonia or other lung infections.

- CT Scan: To detect abscesses, infections, or inflammatory processes in various organs.

- Ultrasound: To visualize abdominal organs and detect abnormalities such as abscesses or cholecystitis.

Bone Marrow Biopsy and Aspiration

Indicated in cases of suspected hematologic malignancies (e.g., chronic myeloid leukemia). It is to evaluate bone marrow cellularity and morphology through MGG staining. It also allows us to perform cytogenetic and molecular studies to identify specific genetic abnormalities.

- Indications:

- Persistent unexplained neutrophilia.

- Presence of abnormal cells in the peripheral blood smear.

- Suspected myeloproliferative disorders.

Other Specialized Tests

- Autoantibody tests: To evaluate for autoimmune diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, lupus).

- Flow cytometry: To identify specific cell populations and abnormalities in hematologic malignancies.

- Molecular genetic testing: To identify specific genetic mutations that are associated with certain hematologic conditions.

By combining these laboratory investigations, clinicians can effectively diagnose the underlying cause of neutrophilia (high neutrophils) and guide appropriate management.

Treatment and Management of Neutrophilia

The treatment and management of neutrophilia (high neutrophils) are primarily focused on addressing the underlying cause. Absolute neutrophilia (high neutrophils) itself is not a disease but a symptom, so the approach varies depending on the specific condition responsible.

Treating the Underlying Cause

- Bacterial Infections: Antibiotics are the mainstay of treatment. The choice of antibiotic depends on the identified pathogen and its susceptibility. Supportive care, such as hydration and fever management, is also essential.

- Inflammatory Conditions: Anti-inflammatory medications, such as corticosteroids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), may be used to reduce inflammation. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) may be necessary for chronic inflammatory conditions like rheumatoid arthritis.

- Hematologic Disorders: Treatment for conditions like chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) may involve targeted therapies (e.g., tyrosine kinase inhibitors), chemotherapy, or stem cell transplantation. Other myeloproliferative neoplasms will have their own specific treatment modalities.

- Stress-Induced Neutrophilia: Addressing the underlying stressor is crucial. Stress reduction techniques, such as relaxation exercises or counseling, may be helpful. In many cases, no medical intervention is needed, as the white count will return to normal after the stressor is removed.

- Drug-Induced Neutrophilia: If a medication is identified as the cause, it may be necessary to adjust the dosage or discontinue the drug. Careful monitoring is essential.

- Tissue Necrosis (e.g., Myocardial Infarction): Treatment focuses on addressing the underlying condition (e.g., restoring blood flow to the heart). Supportive care is essential.

Supportive Care

- Fever Management: Antipyretics (e.g., acetaminophen) can be used to reduce fever.

- Hydration: Maintaining adequate hydration is crucial, especially in cases of infection or inflammation. Intravenous fluids may be necessary in severe cases.

- Pain Management: Analgesics can be used to relieve pain associated with the underlying condition.

Monitoring and Follow-up

- Repeat CBCs: Regular monitoring of the WBC count and ANC is essential to assess the response to treatment.

- Monitoring for Complications: Close monitoring for complications, such as sepsis or organ damage, is necessary in severe cases.

- Follow-up with a Specialist: Patients with persistent or unexplained neutrophilia (high neutrophils) should be referred to a hematologist or other appropriate specialist.

Complications of Prolonged or Severe Neutrophilia

Prolonged or severe absolute neutrophilia (high neutrophils), while often a response to an underlying condition, can itself lead to complications. These complications arise from the sustained increase in neutrophils and the associated inflammatory processes.

Organ Damage from Underlying Disease

This is often the most significant complication. If the absolute neutrophilia (high neutrophils) is caused by a severe infection, inflammatory disease, or malignancy, the primary disease process itself can lead to organ damage. For example:

- Sepsis can lead to multi-organ failure

- Chronic inflammatory diseases can cause tissue damage and organ dysfunction

- Hematologic malignancies can infiltrate and damage organs

Hyperviscosity Syndrome

In extremely high neutrophil counts, particularly in hematologic malignancies like chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), the increased cellularity of the blood can lead to hyperviscosity. This increased blood thickness can impair blood flow, leading to:

- Headaches

- Visual disturbances

- Neurological symptoms (e.g., confusion, dizziness)

- Respiratory distress

Complications from Underlying Malignancy

If the neutrophilia (high neutrophils) is due to a hematologic malignancy, complications related to the malignancy itself can occur, including:

- Infections due to immunosuppression

- Bleeding due to thrombocytopenia (low platelet count)

- Anemia

- Organ infiltration

Increased Risk of Thrombosis

In some cases, especially those with underlying inflammatory conditions or malignancies, prolonged neutrophilia (high neutrophils) can increase the risk of blood clot formation (thrombosis). This is due to the activation of the coagulation cascade by inflammatory mediators.

Inflammatory Damage

Prolonged inflammation, driven by a sustained high neutrophil count, can cause damage to tissues. This can include:

- Damage to blood vessel walls.

- Increased risk of atherosclerosis.

- Tissue fibrosis.

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Damage

Neutrophils release ROS as part of their antimicrobial function. However, excessive ROS production can damage healthy tissues, contributing to inflammation and organ damage.

Importance of a Systematic Approach to Neutrophilia

A systematic approach to neutrophilia (high neutrophils) is crucial for accurate diagnosis and effective management.

Why a Systematic Approach is Essential

- Diverse Etiologies: Neutrophilia (high neutrophils) can be caused by a wide range of conditions, from benign infections to life-threatening malignancies. A systematic approach helps to narrow down the differential diagnosis.

- Preventing Misdiagnosis:cWithout a structured approach, there’s a risk of overlooking serious underlying conditions or misinterpreting the significance of the elevated neutrophil count. This can lead to inappropriate treatment or delayed diagnosis.

- Guiding Investigations: A systematic approach ensures that appropriate laboratory and imaging studies are ordered, avoiding unnecessary tests and costs. It helps to prioritize investigations based on the clinical presentation and initial findings.

- Optimizing Management: A systematic approach allows for the development of a tailored treatment plan that addresses the specific cause of neutrophilia. It also facilitates effective monitoring of treatment response and early detection of complications.

- Improved Patient Outcomes: By ensuring accurate diagnosis and timely intervention, a systematic approach ultimately leads to better patient outcomes.

Components of a Systematic Approach

- Detailed History and Physical Examination: Gather a thorough medical history, including symptoms, medications, and risk factors. Perform a comprehensive physical examination to identify signs of infection, inflammation, or other underlying conditions.

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) with Differential: Confirm the presence of neutrophilia and calculate the absolute neutrophil count (ANC). Evaluate other CBC parameters, such as hemoglobin, platelets, and red blood cell morphology.

- Peripheral Blood Smear: Examine the morphology of neutrophils and other blood cells. Identifying immature neutrophils or abnormal cells.

- Inflammatory Markers: Measure CRP, ESR, and procalcitonin to assess the degree of inflammation and differentiate between bacterial and other causes.

- Microbiological Studies: Perform blood cultures, urine cultures, and other relevant cultures to identify infectious agents.

- Imaging Studies: Use chest X-rays, CT scans, or ultrasounds to visualize internal organs and detect abnormalities.

- Bone Marrow Biopsy (if indicated): Perform a bone marrow biopsy to evaluate bone marrow cellularity and morphology in cases of suspected hematologic malignancies.

- Clinical Correlation: Analyze all gathered information to form a differential diagnosis. Correlate the lab findings with the patient’s symptoms.

- Follow-up and Monitoring: Closely monitor the patient’s response to treatment and repeat lab testing. Address any complications that arise.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Is neutrophilia life threatening?

Neutrophilia (high neutrophils) itself is not a disease, but rather a sign of an underlying condition. Therefore, whether or not it’s “life-threatening” depends entirely on what’s causing it.

- Neutrophilia as a Sign: Neutrophilia (high neutrophils) indicates an increase in neutrophils. This increase is often a response to the body battling an infection or inflammation.

- When It Can Be Serious: If the underlying cause is a severe infection (like sepsis), a serious inflammatory condition, or a hematologic malignancy (like leukemia), then the situation can be life-threatening. In cases of extremely high neutrophil counts, hyperviscosity syndrome can occur, which can also be a medical emergency.

- When It’s Less Serious: Mild neutrophilia (high neutrophils) can be caused by less serious factors, such as stress, smoking, or certain medications. In these cases, the neutrophilia (high neutrophils) itself is not life-threatening, but addressing the underlying factor might be.

Can stress cause high neutrophils?

Yes, stress can indeed cause high neutrophils. Stress can cause high neutrophil counts through the release of cortisol and adrenaline.

These hormones trigger the release of neutrophils from the bone marrow and the margination pool into the bloodstream. This physiological response, while transient and usually mild, is important to differentiate from neutrophilia caused by infections or other pathological conditions.

Typically, stress-induced neutrophilia won’t exhibit a “left shift” (an increase in immature neutrophils), helping clinicians distinguish it from infection-related neutrophilia.

Does COVID cause high neutrophils?

Yes, COVID-19 can cause high neutrophil counts. COVID-19, being an infectious disease, triggers an inflammatory response in the body. This response often includes an increase in neutrophils, which are a key part of the immune system’s defense against pathogens.

The severity of the neutrophilia can vary depending on the severity of the COVID-19 infection. In severe cases, the neutrophil count can be significantly elevated. Furthermore, COVID-19 can also cause a “left shift,” meaning there’s an increase in immature neutrophils, indicating the bone marrow is rapidly producing these cells to combat the infection.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Goldberg S, Hoffman J. Clinical Hematology Made Ridiculously Simple, 1st Edition: An Incredibly Easy Way to Learn for Medical, Nursing, PA Students, and General Practitioners (MedMaster Medical Books). 2021.

- Keohane EM, Otto CN, Walenga JM. Rodak’s Hematology 6th Edition (Saunders). 2019.

- Blumenreich MS. The White Blood Cell and Differential Count. In: Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, editors. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd edition. Boston: Butterworths; 1990. Chapter 153.

- Tahir N, Zahra F. Neutrophilia. [Updated 2023 Apr 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.