TL;DR

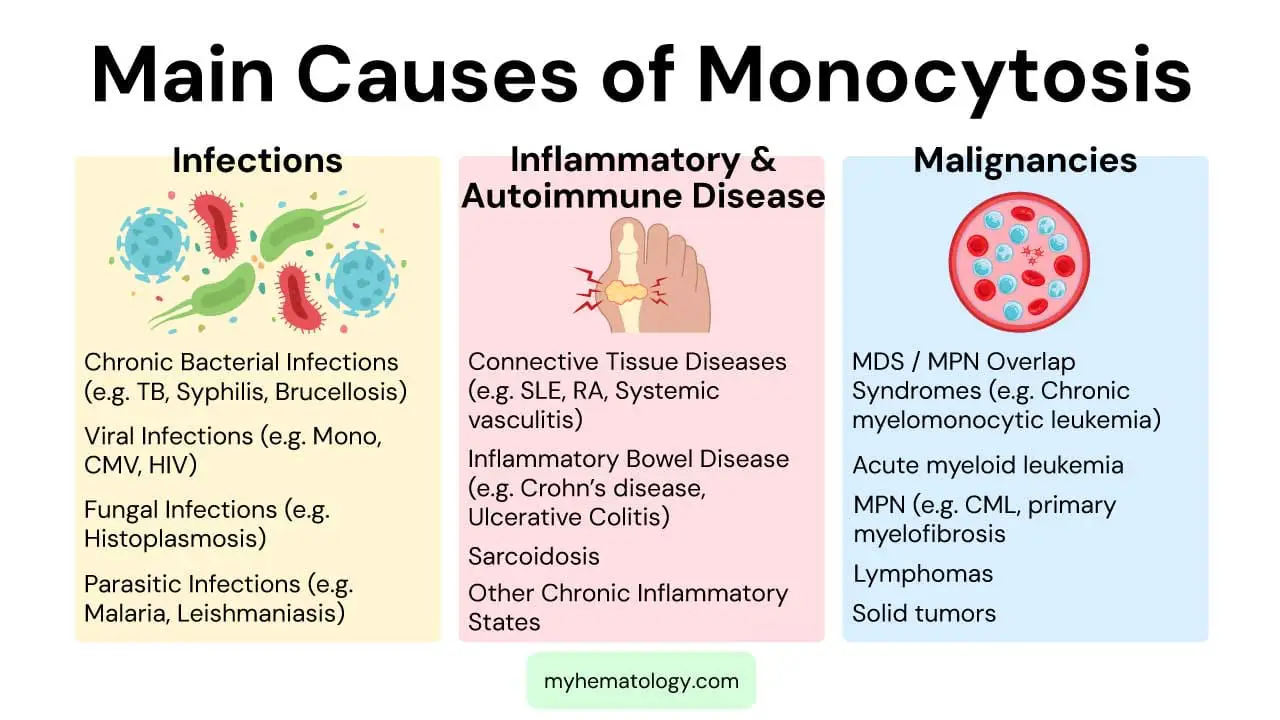

Monocytosis or high monocytes is an increased absolute monocyte count in peripheral blood, typically > 0.8−1.0 x 109/L. It’s a non-specific indicator of an underlying condition, not a disease itself.

- Causes ▾: Broadly categorized into infections (chronic bacteria, viral), inflammatory/autoimmune diseases (e.g., RA, SLE, IBD), and malignancies (crucially CMML, AML). Other causes include post-splenectomy and bone marrow recovery.

- Symptoms ▾: Monocytosis itself rarely causes symptoms; symptoms stem from the underlying disease (e.g., fever from infection, fatigue from malignancy).

- Diagnosis ▾: Requires a thorough history, physical exam, CBC with differential & peripheral blood smear. Further tests (cultures, autoantibodies, bone marrow biopsy, molecular studies) are guided by suspicion.

- Treatment ▾: Always targets the underlying cause (e.g., antibiotics for infection, chemotherapy for leukemia).

*Click ▾ for more information

Introduction

Monocytosis (high monocytes) is an increase in the absolute number of monocytes in the peripheral blood above the normal reference range, typically defined as an absolute monocyte count (AMC) greater than 0.8−1.0 x 109/L (or 800−1000 cells/µL).

It is not a disease itself but rather an indicator of an underlying condition. It can be associated with a wide array of conditions, including chronic infections (like tuberculosis or endocarditis), inflammatory and autoimmune diseases (such as rheumatoid arthritis or inflammatory bowel disease), and importantly, certain hematological malignancies (especially myelodysplastic syndromes and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia). Therefore, recognizing monocytosis necessitates a thorough clinical and laboratory evaluation to determine the specific diagnosis and guide appropriate management.

What are Monocytes?

Monocytes originate from the myeloid lineage in the bone marrow, where they develop from hematopoietic stem cells. Once released into the bloodstream, they play a crucial role in innate immunity. Their primary functions include phagocytosis, engulfing pathogens and cellular debris, and antigen presentation, processing antigens and presenting them to T cells to initiate adaptive immune responses. They also contribute to immune regulation through cytokine production.

Monocytes have a relatively short circulating lifespan in the blood, typically lasting only about 1 to 3 days. However, they are highly mobile and can rapidly migrate into various tissues throughout the body. Once in the tissues, they differentiate and mature into long-lived tissue-resident cells, primarily macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs), which then perform specialized functions within those specific environments. This transition into macrophages and DCs highlights their critical role as precursors to key immune cells found in virtually every tissue.

Definition of Monocytosis (High Monocytes)

Monocytosis (high monocytes) is generally defined by an absolute monocyte count (AMC) above the normal upper limit. While the exact threshold can vary slightly, a common definition is an AMC greater than 0.8 – 1.0 x 109/L (or 800 – 1000 cells/µL).

Additionally, monocytes accounting for greater than 10% of the total WBC count is also often used as a criterion, especially when considered alongside the absolute count. For persistent monocytosis, the World Health Organization (WHO) has a stricter definition for certain conditions, sometimes requiring an AMC > 1 x 109/L with monocytes accounting for > 10% of leukocytes persisting for > 3 months.

Absolute Monocyte Count (AMC) and Normal Range

The Absolute Monocyte Count (AMC) represents the actual number of monocytes per unit volume of blood. It is calculated by multiplying the total white blood cell (WBC) count by the percentage of monocytes from the differential.

The normal range for AMC in adults typically falls between 0.2 – 0.8 x 109/L (or 200−800 cells/µL).

Relative and Absolute Monocytosis

- Absolute Monocytosis refers to an increase in the actual number of monocytes in the blood, as determined by the AMC. This is the more clinically significant parameter, as it directly reflects an increased production or mobilization of monocytes.

- Relative Monocytosis occurs when the percentage of monocytes is elevated, but the absolute monocyte count remains within the normal range. This can happen if other white blood cell types (e.g., neutrophils, lymphocytes) are decreased, making the monocyte percentage appear higher even if their total number is not increased. For example, if the total WBC count is low, but the monocyte count is normal, the percentage of monocytes will be relatively higher. While relative monocytosis might sometimes offer clues, absolute monocytosis is generally considered the more reliable indicator of an underlying pathological process.

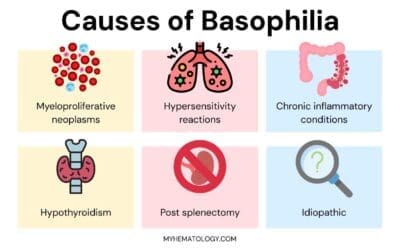

Causes of Monocytosis

Monocytosis, an elevated absolute monocyte count, is a non-specific finding that can point to a wide range of underlying conditions. The causes are broadly categorized as reactive (due to an underlying illness or stress) or neoplastic (due to a bone marrow malignancy).

Infections (Common Reactive Causes)

Monocytes are key players in the immune response, particularly against chronic and intracellular pathogens. Therefore, infections are a very common cause of monocytosis.

- Chronic Bacterial Infections: These often lead to sustained monocyte elevation as the body mounts a prolonged defense.

- Tuberculosis (TB): A classic cause, where monocytes differentiate into macrophages that form granulomas.

- Subacute Bacterial Endocarditis (SBE): Chronic infection of heart valves.

- Brucellosis: A bacterial infection acquired from animals.

- Syphilis: A chronic bacterial sexually transmitted infection.

- Viral Infections

- Infectious Mononucleosis (Epstein-Barr Virus – EBV): Often presents with atypical lymphocytes, but monocytosis can also be seen.

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Infection: Similar to EBV, it can cause lymphocytosis and monocytosis.

- HIV Infection: Especially during chronic phases or opportunistic infections.

- Fungal Infections: Systemic fungal infections can elicit a strong monocytic response.

- Histoplasmosis, Cryptococcosis, Coccidioidomycosis: Examples of deep fungal infections.

- Parasitic Infections

- Malaria: The body’s attempt to clear infected red blood cells.

- Leishmaniasis (Kala-Azar): A parasitic disease affecting macrophages.

Inflammatory and Autoimmune Diseases

Monocytes are integral to inflammatory processes and tissue damage, and their numbers can rise in various chronic inflammatory and autoimmune conditions.

- Connective Tissue Diseases

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE): A chronic autoimmune disease affecting multiple organs.

- Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA): Chronic inflammatory disorder affecting joints.

- Systemic Vasculitis: Inflammation of blood vessels.

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

- Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis: Chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract.

- Sarcoidosis: A multisystem inflammatory disease characterized by granulomas.

- Other Chronic Inflammatory States: Any persistent inflammation can lead to high monocytes count.

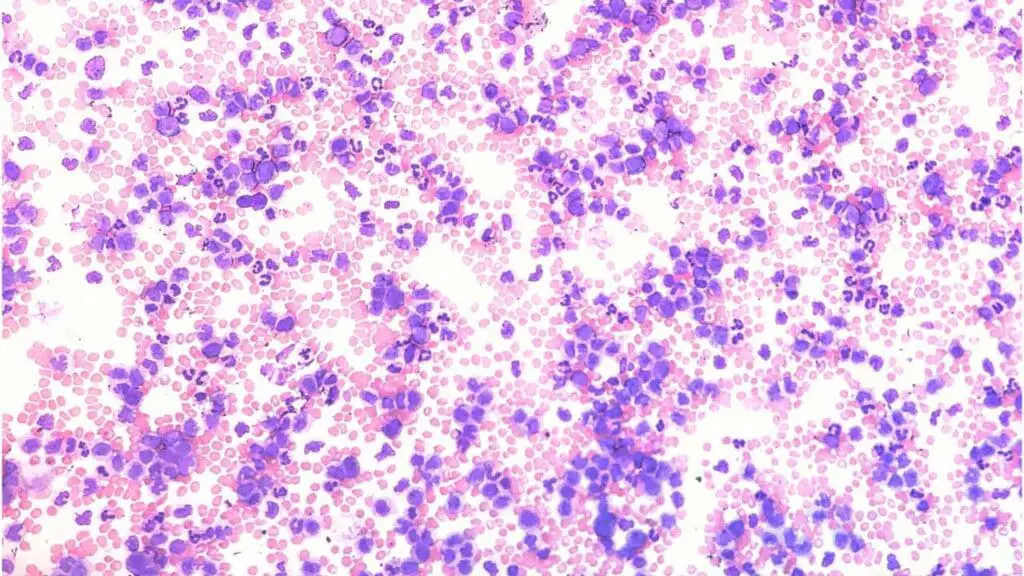

Malignancies (Important to Consider, especially if persistent and unexplained)

Monocytosis (high monocytes) can be a diagnostic criterion or an associated finding in several hematological and solid malignancies. It’s particularly concerning if the monocytosis is persistent, high, or accompanied by other cytopenias or abnormal cell morphology.

- Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS) / Myeloproliferative Neoplasms (MPN) Overlap Syndromes

- Chronic Myelomonocytic Leukemia (CMML): This is a key diagnosis to consider with persistent monocytosis. CMML is defined by a persistent peripheral blood monocytosis (≥1×109/L and monocytes ≥10% of WBCs) along with features of both myelodysplastic syndrome (ineffective blood cell production, dysplasia) and myeloproliferative neoplasm (proliferation of myeloid cells).

- Juvenile Myelomonocytic Leukemia (JMML): A rare childhood disorder with overlapping features of MDS and MPN, also characterized by monocytosis.

- Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML)

- AML with monocytic differentiation (M4, M5 subtypes): These subtypes are characterized by a significant monocytic component and will show an increase in immature monocytes (monoblasts and promonocytes).

- Myeloproliferative Neoplasms (MPN): While less common than CMML, monocytosis can be seen in some MPNs.

- Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML): Especially in accelerated or blast phases, or sometimes with p190 BCR-ABL1 isoform.

- Primary Myelofibrosis (PMF): May have variable monocytosis.

- Hodgkin Lymphoma and Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: Monocytosis can be present, though typically less pronounced than in myeloid malignancies.

- Solid Tumors: Paraneoplastic monocytosis can occur with various solid tumors, likely due to cytokine production by the tumor or host response.

Other Causes

- Post-Splenectomy: The spleen is a reservoir and filter for monocytes. After splenectomy, monocytes that would normally be removed by the spleen remain in circulation, leading to a compensatory monocytosis.

- Recovery Phase of Marrow Suppression: As the bone marrow recovers from aplasia (e.g., due to chemotherapy, radiation, or certain infections), monocytes often rebound robustly, leading to a transient monocytosis.

- Stress Response: Severe physiological stress or trauma can sometimes induce a mild, transient monocytosis.

- Medications: Certain drugs, like corticosteroids (especially during withdrawal), or growth factors (e.g., G-CSF), can sometimes cause high monocytes.

- Lipid Storage Diseases: Rare genetic disorders that affect lipid metabolism can lead to monocyte accumulation in tissues.

- Pregnancy

Clinical Presentation and Symptoms

Monocytosis itself typically does not cause specific signs or symptoms. Instead, the signs and symptoms observed are almost always a reflection of the underlying condition that is causing the elevated monocyte count.

When you see monocytosis, you should think about the conditions that commonly cause it, and then consider the symptoms associated with those conditions.

Infections (especially chronic ones)

- Fever: Often low-grade and persistent in chronic infections (e.g., tuberculosis, subacute bacterial endocarditis).

- Fatigue: Common in many chronic illnesses.

- Weight loss: Unexplained weight loss can point to chronic infections or malignancies.

- Night sweats: Particularly suggestive of tuberculosis or certain lymphomas.

- Specific localized symptoms: Cough (TB), dental pain/murmur (endocarditis), skin lesions (syphilis, leishmaniasis).

- Lymphadenopathy: Enlarged lymph nodes (e.g., infectious mononucleosis, HIV).

- Splenomegaly: Enlarged spleen (e.g., malaria, infectious mononucleosis, some chronic bacterial infections).

Inflammatory and Autoimmune Diseases

- Fatigue: A very common symptom.

- Malaise: General feeling of unwellness.

- Joint pain/swelling (Arthralgia/Arthritis): Common in rheumatoid arthritis, SLE.

- Skin rashes: Characteristic of SLE, vasculitis.

- Specific organ system symptoms: Depending on the organ affected (e.g., abdominal pain and diarrhea in Inflammatory Bowel Disease; shortness of breath and cough in Sarcoidosis affecting the lungs).

- Weight loss.

Malignancies (especially Myelodysplastic Syndromes/CMML, Leukemias, Lymphomas)

- Constitutional Symptoms (B symptoms)

- Unexplained fever.

- Unexplained weight loss.

- Drenching night sweats.

- Fatigue, pallor: Due to associated anemia.

- Easy bruising or bleeding: Due to associated thrombocytopenia.

- Recurrent infections: Due to dysfunctional or decreased neutrophils (neutropenia).

- Lymphadenopathy: Enlarged lymph nodes (especially in lymphomas).

- Splenomegaly and/or Hepatomegaly: Enlarged spleen and/or liver (common in myeloproliferative neoplasms, leukemias).

- Bone pain: Less common but can occur in certain leukemias.

When Monocytosis (High Monocytes) Might Be a Direct Clue (Subtle Indications)

While monocytes don’t cause symptoms, very high or dysplastic monocytes (seen on a blood smear) might indirectly point towards certain conditions even before a formal diagnosis. For example:

- Persistent, high monocytosis (e.g., >1×109/L for months) in an otherwise seemingly healthy individual should raise strong suspicion for Chronic Myelomonocytic Leukemia (CMML), even before other overt symptoms develop.

- The presence of immature monocytes (monoblasts/promonocytes) on the peripheral blood smear is a critical visual clue highly suggestive of Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) with monocytic differentiation, which would then present with rapid onset symptoms like fatigue, bleeding, and infection.

Laboratory Investigations

Diagnosing the cause of monocytosis (high monocytes) requires a systematic approach, integrating clinical assessment with various laboratory and sometimes imaging investigations. The goal is to differentiate between reactive (non-cancerous) and neoplastic (cancerous) causes, and then pinpoint the specific underlying condition.

Initial Assessment and Baseline Investigations

Comprehensive History and Physical Examination

- History: Crucial for identifying clues. Ask about:

- Duration of monocytosis: Acute vs. chronic (persistent monocytosis for >3 months is more concerning for malignancy).

- Constitutional symptoms: Fever, unexplained weight loss, night sweats (B symptoms), which are common in infections, chronic inflammation, and malignancies.

- Infectious exposures: Recent travel, sick contacts, animal exposures, tick bites, tuberculosis exposure.

- Autoimmune symptoms: Joint pain, rashes, dry eyes/mouth, muscle weakness.

- Bleeding/bruising or recurrent infections: Suggestive of bone marrow dysfunction.

- Medication history: Certain drugs (e.g., corticosteroids, G-CSF) can cause monocytosis.

- Past medical history: Previous splenectomy, known chronic diseases.

- Smoking status: Chronic smokers can have mild monocytosis.

- Physical Examination

- LymphadenopathyLymphadenopathy: Enlarged lymph nodes (infections, lymphomas).

- Splenomegaly/Hepatomegaly: Enlarged spleen and/or liver (common in chronic infections, myeloproliferative neoplasms, leukemias, lipid storage disorders).

- Skin lesions: Rashes, nodules, evidence of infection or autoimmune disease.

- Joint examination: Signs of arthritis.

- Oral cavity: For signs of infection or inflammation.

Complete Blood Count (CBC) with Differential

Confirm Absolute Monocyte Count (AMC) is elevated. This is the primary finding.

Evaluation of other cell lines:

- Anemia (low red blood cells): Common in chronic diseases, autoimmune conditions, and particularly in myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and leukemias.

- Thrombocytopenia (low platelets) or Thrombocytosis (high platelets): Can indicate bone marrow dysfunction or myeloproliferative processes.

- Leukocytosis (high WBC) or Leukopenia (low WBC): Provides context for the monocytosis (high monocytes). For example, monocytosis (high monocytes) with accompanying neutropenia or pancytopenia (low all cell lines) is highly suspicious for MDS/AML.

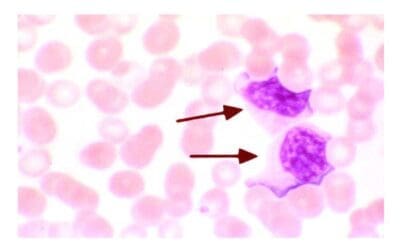

Peripheral Blood Smear (PBS) Examination

- Monocyte morphology: Look for dysplastic features (abnormal shape, size, nuclear abnormalities) suggestive of MDS or CMML.

- Presence of immature myeloid cells (blasts, promonocytes): A hallmark of acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

- Abnormal neutrophils/other cell lines: Evidence of dysplasia or abnormal maturation.

- Abnormal lymphocytes: If lymphoproliferative disorder is suspected.

- Red blood cell morphology: Teardrop cells (myelofibrosis), macro-ovalocytes (MDS).

Targeted Investigations Based on Clinical Suspicion

After the initial assessment, the subsequent workup is guided by the most likely underlying cause.

For mild, transient monocytosis (high monocytes) without concerning features, a repeat CBC in 2-4 weeks might be sufficient to confirm resolution. If monocytosis (high monocytes) persists or worsens, or if new symptoms develop, further investigations are warranted.

Treatment and Management

The treatment and management of monocytosis (high monocytes) are not directed at the monocytosis itself, but rather at the underlying disease or condition causing the elevated monocyte count. Once the extensive diagnostic workup identifies the specific etiology, treatment focuses entirely on addressing that primary condition. As the underlying disease improves or resolves, the monocytosis (high monocytes) typically normalizes.

While not treating monocytosis (high monocytes) directly, managing the symptoms of the underlying disease is a crucial part of patient care. This may include:

- Pain management

- Antipyretics for fever

- Nutritional support for weight loss

- Transfusions for severe anemia or thrombocytopenia

- Antibiotics for opportunistic infections (e.g., in immunocompromised patients with malignancy).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Does monocytosis mean leukemia?

No, monocytosis (high monocytes) does not automatically mean leukemia.

While certain types of leukemia can cause high monocytes, it’s far from the only cause. As discussed above, monocytosis (high monocytes) is a non-specific finding that can result from a wide range of conditions, most of which are not cancerous.

What drugs can cause monocytosis?

While monocytosis (high monocytes) is most commonly caused by infections, inflammation, or malignancy, certain medications can also lead to an elevated monocyte count. These are typically reactive and resolve after the drug is discontinued.

Here are some drugs that can cause high monocytes:

- Corticosteroids: Especially during the recovery or withdrawal phase, or in some cases, during therapy itself.

- Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor (G-CSF): Used to stimulate white blood cell production, and can increase monocytes.

- Atypical Antipsychotics: Such as Ziprasidone.

- Lithium: Used in mood disorders.

- Allopurinol: Used for gout.

- Some Antibiotics: While antibiotics treat infections that cause monocytosis, a few have been anecdotally reported to cause it as a side effect (e.g., certain cephalosporins like Ceftriaxone, Moxifloxacin).

- Anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG): An immunosuppressant.

What vitamin deficiency causes high monocytes?

No specific vitamin deficiency is a direct or common cause of high monocytes. If monocytosis is present, other causes like infections, inflammation, or malignancies should be the primary considerations, and vitamin deficiencies (B12, folate) would typically be investigated in the context of associated anemia or other cytopenias.

Are monocytes high after COVID?

The monocyte count can be affected by COVID-19 infection, and the changes can vary depending on the phase and severity of the disease.

The acute phase of COVID-19 can show varied monocyte dynamics, there is considerable evidence that monocytes can be high and remain activated for an extended period after COVID-19 infection, particularly in individuals experiencing Long COVID symptoms. This persistent monocytosis (high monocytes) often reflects ongoing systemic inflammation.

Can vaccines cause high monocytes?

Yes, vaccines can cause a temporary increase in monocyte counts, and definitely lead to monocyte activation and changes in their functional profile. This is generally a normal and expected part of the immune response to vaccination.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Gordon S, Taylor PR. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005 Dec;5(12):953-64. doi: 10.1038/nri1733. PMID: 16322748.

- https://ashpublications.org/thehematologist/article/doi/10.1182/hem.V13.4.5658/462753/Ask-the-Hematopathologists-Diagnostic-Approach-to

- Lynch DT, Hall J, Foucar K. How I investigate monocytosis. Int J Lab Hematol. 2018 Apr;40(2):107-114. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.12776. Epub 2018 Jan 18. PMID: 29345409.

- Christensen, M. E., Siersma, V., Kriegbaum, M., Lind, B. S., Samuelsson, J., Østgård, L. S. G., Grønbaek, K., & Andersen, C. L. (2023). Monocytosis in primary care and risk of haematological malignancies. European journal of haematology, 110(4), 362–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejh.13911

- Dutta, P., & Nahrendorf, M. (2014). Regulation and consequences of monocytosis. Immunological reviews, 262(1), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/imr.12219

- Mangaonkar, A. A., Tande, A. J., & Bekele, D. I. (2021). Differential Diagnosis and Workup of Monocytosis: A Systematic Approach to a Common Hematologic Finding. Current hematologic malignancy reports, 16(3), 267–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11899-021-00618-4