TL;DR

Lymphocytosis or High lymphocytes is an elevated absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) in the peripheral blood, typically above 4.0 x 109/L in adults.

- Lymphocyte Types ▾: Lymphocytes (B cells, T cells, NK cells) are crucial immune cells involved in adaptive and innate immunity.

- Causes ▾: Causes of high lymphocytes are broadly classified into reactive (benign), usually due to infections or stress, and malignant (clonal), indicating lymphoproliferative disorders like leukemia.

- Common Reactive Causes: Viral infections (e.g., EBV, CMV), bacterial infections (e.g., Bordetella pertussis), and acute stress are frequent causes of high lymphocytes.

- Key Malignant Causes: Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) is the most common adult malignancy presenting with lymphocytosis. Other leukemias and lymphomas can also present this way.

- Symptoms ▾: Lymphocytosis or high lymphocytes itself is asymptomatic; symptoms arise from the underlying cause (e.g., fever, fatigue, swollen lymph nodes in infections or malignancies).

- Diagnosis ▾: Initial steps involve a Complete Blood Count (CBC) with differential and a crucial peripheral blood smear examination to assess lymphocyte morphology. If malignancy is suspected, flow cytometry is essential for immunophenotyping and clonality assessment, followed by molecular/cytogenetic studies or bone marrow biopsy if needed.

- Treatment ▾: Management is entirely dependent on the cause. Reactive lymphocytosis is managed by treating the underlying condition. Malignant lymphocytosis requires specific cancer therapies, often involving targeted drugs or chemotherapy.

- Prognosis: Excellent for reactive causes, as lymphocytosis resolves. Varies widely for malignant causes of high lymphocytes, depending on the specific diagnosis and treatment response.

*Click ▾ for more information

Introduction

Lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes) is a condition characterized by an increase in the absolute number of lymphocytes in the peripheral blood above the normal range. In adults, this is generally defined as an absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) greater than 4.0 x 109/L, though normal ranges can vary slightly with age. It can be a temporary, benign response to various infections or inflammatory conditions (reactive lymphocytosis), or it can indicate a serious underlying hematologic malignancy, such as leukemia or lymphoma (malignant lymphocytosis).

Lymphocytes

Lymphocytes are a crucial type of white blood cell (leukocyte) that plays a central role in the body’s immune system, fighting off infections and diseases. They originate in the bone marrow and are primarily found in the blood, lymph nodes, spleen, and other lymphoid tissues.

There are three main types of lymphocytes.

- B cells (B lymphocytes): These are primarily responsible for humoral immunity. When activated, B cells differentiate into plasma cells, which produce large quantities of antibodies. Antibodies are proteins that specifically bind to foreign substances (antigens) like viruses, bacteria, and toxins, marking them for destruction by other immune cells or neutralizing them directly. Some B cells also develop into memory B cells, providing long-lasting immunity.

- T cells (T lymphocytes): These are key players in cell-mediated immunity. T cells mature in the thymus (hence “T” cell) and have highly specific receptors for antigens. There are several subtypes:

- Helper T cells (CD4+ T cells): These act as “conductors” of the immune response, releasing chemical messengers called cytokines that help activate and direct other immune cells, including B cells and cytotoxic T cells.

- Cytotoxic T cells (CD8+ T cells): Also known as “killer T cells,” these directly recognize and destroy body cells that have been infected by viruses or have become cancerous.

- Regulatory T cells (Tregs): These help to suppress or control immune responses, preventing excessive inflammation and autoimmune reactions.

- Memory T cells: Like memory B cells, these provide long-term immunity by remembering past invaders and mounting a faster, stronger response upon re-exposure.

- Natural Killer (NK) cells: These are part of the innate immune system, providing a rapid, non-specific defense. NK cells can identify and kill abnormal cells, such as cancer cells and cells infected with viruses, without needing prior activation or specific antigen recognition. They recognize changes in the surface molecules of target cells (e.g., loss of MHC class I) and then release cytotoxic granules to destroy them.

Normal Range in Peripheral Blood

The normal range for the total absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) in peripheral blood varies with age, with children typically having higher counts than adults. There are also some slight variations between laboratories.

- Adults: Approximately 1.0 to 4.8 x 109/L (or 1,000 to 4,800 cells per microliter).

- Children (under 2 years): Approximately 3.0 to 9.5 x 109/L (or 3,000 to 9,500 cells per microliter).

- Children (around 6 years): The lower limit of normal is typically around 1.5 x 109/L (or 1,500 cells per microliter).

Absolute and Relative Lymphocytosis

The distinction between absolute and relative lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes) lies in how the lymphocyte count is expressed and what it signifies in the context of the total white blood cell (WBC) count.

Absolute Lymphocytosis (High Lymphocytes)

Absolute lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes) refers to an actual increase in the total number of lymphocytes per unit volume of blood, exceeding the established normal upper limit for that age group.

It’s determined by multiplying the total white blood cell count (WBC) by the percentage of lymphocytes in the differential count.

Formula: Absolute Lymphocyte Count (ALC) = Total WBC Count x (% Lymphocytes / 100)

An elevated absolute lymphocyte count directly indicates an increased production or decreased clearance of lymphocytes. This can be due to:

- Reactive causes: Viral infections (e.g., infectious mononucleosis, CMV, pertussis), certain bacterial infections, stress, or some autoimmune conditions.

- Malignant causes: Lymphoproliferative disorders like chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), or certain lymphomas in their leukemic phase.

Relative Lymphocytosis (High Lymphocytes)

Relative lymphocytosis or high lymphocytes occurs when the percentage of lymphocytes among the total white blood cells is higher than normal, but the absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) remains within the normal range.

Relative lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes) implies that while lymphocytes make up a larger proportion of the WBCs, this is often because other types of white blood cells (most commonly neutrophils) are decreased. It doesn’t necessarily mean there’s an overproduction of lymphocytes. Common scenarios include:

- Neutropenia: A decrease in neutrophils (e.g., due to certain infections, bone marrow suppression, or drug reactions) can make lymphocytes appear relatively increased even if their absolute number is normal.

- Normal finding in young children: Infants and young children naturally have a higher percentage of lymphocytes compared to adults, so relative lymphocytosis can be a normal physiological finding in this age group.

Causes of Lymphocytosis (High Lymphocytes)

Lymphocytosis, an elevated absolute lymphocyte count, can stem from a wide array of underlying conditions, broadly categorized into reactive (benign) and malignant (lymphoproliferative) causes.

Reactive (Benign) Lymphocytosis

This is the most common cause of lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes) and indicates a robust immune response to an infection, inflammation, or stressor. The lymphocytes in these cases are typically polyclonal (meaning they are a diverse population of cells) and often show reactive morphological changes (e.g., atypical lymphocytes).

Infections

- Viral Infections (Most Common Cause)

- Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV): The classic cause of infectious mononucleosis (“mono” or glandular fever). Characterized by fever, sore throat, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and often prominent atypical lymphocytes (Downey cells) on the blood smear.

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV): Can cause a mononucleosis-like illness, often without pharyngitis.

- Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV): Acute seroconversion can present with a mononucleosis-like syndrome and lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes). Chronic HIV infection, however, often leads to lymphopenia (decreased lymphocytes).

- Hepatitis Viruses (HAV, HBV, HCV)

- Other Viruses: Influenza, Measles, Rubella, Mumps, Adenovirus, Varicella-Zoster Virus (chickenpox/shingles), Parvovirus B19.

- Bacterial Infections

- Bordetella pertussis (Whooping Cough): Causes a characteristic marked lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes), often with small, mature-appearing lymphocytes.

- Brucellosis.

- Tuberculosis (Mycobacterium tuberculosis).

- Syphilis: Especially in its secondary stage.

- Cat-Scratch Disease (Bartonella henselae): Can cause lymphadenopathy and lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes).

- Parasitic Infections

- Toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma gondii): Can cause a mononucleosis-like illness with atypical lymphocytes.

- Babesiosis.

Other Reactive Conditions

- Stress Response: Severe physiological stress, such as major trauma, myocardial infarction, seizures, or acute medical emergencies, can trigger a transient lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes).

- Drug Reactions: Certain medications can induce a hypersensitivity reaction leading to lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes). Examples include anticonvulsants (e.g., phenytoin), and in some cases, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome.

- Post-splenectomy State (Asplenia): The spleen normally filters and removes aged or damaged blood cells, including lymphocytes. After splenectomy (surgical removal of the spleen), lymphocytes can accumulate in the peripheral blood, leading to a persistent, mild to moderate lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes).

- Autoimmune Diseases: While many autoimmune conditions (e.g., Systemic Lupus Erythematosus) are associated with lymphopenia, some, particularly those with chronic inflammation, can occasionally cause a reactive lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes) (e.g., Sjögren’s syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis in some phases, or specific vasculitides).

- Endocrine Disorders: Rarely, conditions like thyrotoxicosis (hyperthyroidism) can be associated with mild lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes).

- Smoking: Chronic heavy smoking can lead to a persistent, mild lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes).

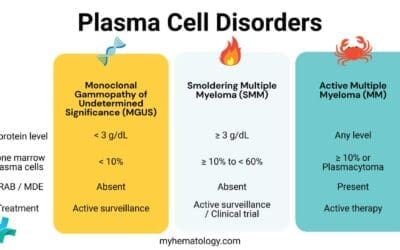

Malignant Lymphocytosis (Lymphoproliferative Disorders)

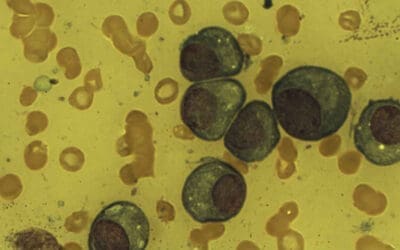

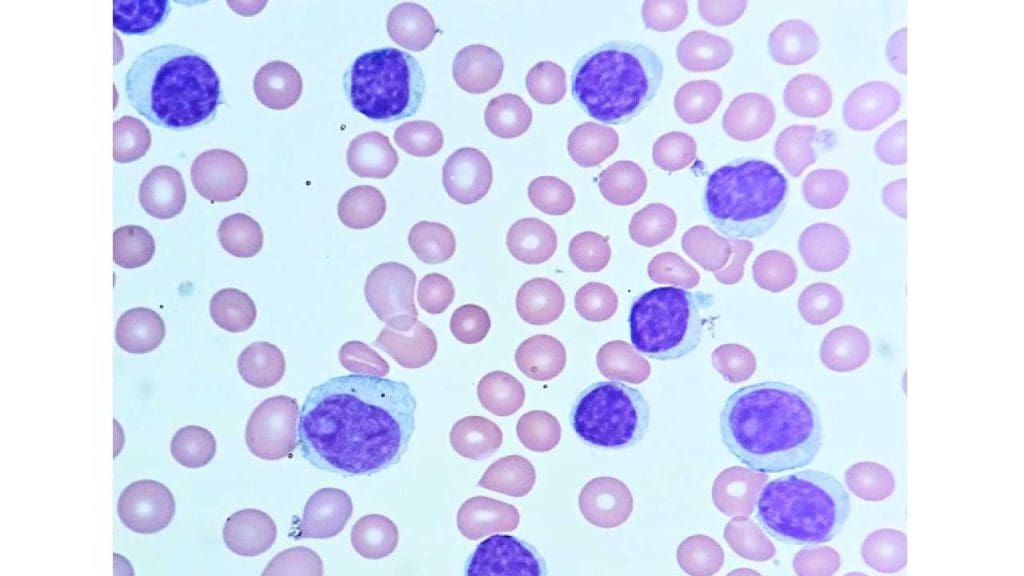

This category involves the uncontrolled proliferation of a clonal (derived from a single cell) population of lymphocytes, indicating a type of blood cancer. The lymphocytes may appear morphologically abnormal or immature.

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL)

The most common leukemia in adults, typically affecting older individuals. It is characterized by a persistent, often very high, absolute lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes) of small, mature-appearing B lymphocytes. “Smudge cells” (fragile lymphocytes that rupture during smear preparation) are a classic finding on the peripheral blood smear. Diagnosis is confirmed by flow cytometry showing a clonal B-cell population with characteristic immunophenotype (CD5+, CD19+, CD20dim, CD23+).

Other Mature B-cell Neoplasms with Leukemic Phase

- Hairy Cell Leukemia (HCL): Characterized by pancytopenia and distinctive “hairy cells” (lymphocytes with fine cytoplasmic projections) in the peripheral blood and bone marrow.

- Splenic Marginal Zone Lymphoma (SMZL): Often presents with splenomegaly and villous lymphocytes (lymphocytes with polar cytoplasmic projections).

- Follicular Lymphoma (FL): Less commonly, FL cells can “spill” into the peripheral blood, causing lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes).

- Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL): Some variants of MCL can have a leukemic presentation with circulating mantle cells.

- B-cell Prolymphocytic Leukemia (B-PLL): A rare, aggressive leukemia characterized by a high count of prolymphocytes (larger lymphocytes with prominent nucleoli).

Mature T-cell and NK-cell Neoplasms with Leukemic Phase

- T-cell Prolymphocytic Leukemia (T-PLL): An aggressive leukemia with a high count of prolymphocytes, often involving skin and lymph nodes.

- Large Granular Lymphocytic (LGL) Leukemia: Can be T-LGL or NK-LGL leukemia. Characterized by a persistent expansion of large granular lymphocytes, often associated with cytopenias (anemia, neutropenia) and autoimmune phenomena.

- Sézary Syndrome: The leukemic phase of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (Mycosis Fungoides). Characterized by pruritic skin lesions and circulating “Sézary cells” (T lymphocytes with cerebriform nuclei).

- Adult T-cell Leukemia/Lymphoma (ATLL): Caused by Human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1), endemic in certain regions. Can present with diverse clinical features, including lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes) with pleomorphic lymphocytes.

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL)

While often associated with blast cells and cytopenias, some cases of ALL, particularly in children, can initially present with a high WBC count dominated by lymphoblasts, which might be mistakenly interpreted as lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes) without careful morphological review.

Signs and Symptoms of Lymphocytosis (High Lymphocytes)

Lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes) itself is a laboratory finding, meaning it’s an elevated count of lymphocytes in the blood. Therefore, it doesn’t have specific “symptoms” of its own. Instead, the signs and symptoms associated with lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes) are those of the underlying condition causing the elevated lymphocyte count.

These manifestations can vary widely depending on whether the cause is reactive (benign) or malignant (cancerous), and which specific illness is present.

General and Non-Specific Symptoms (Can be present in various causes)

Many symptoms are shared across different conditions causing lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes), making it important to consider the full clinical picture.

- Fatigue and Malaise: Feeling unusually tired or generally unwell. This is a very common symptom in both infections and chronic illnesses, including malignancies.

- Fever: Elevated body temperature, often indicating an infection or an inflammatory process. In malignancies like lymphoma or leukemia, “B symptoms” (fever, night sweats, unexplained weight loss) can be present.

- Night Sweats: Excessive sweating during sleep, often drenching, that is not related to environmental temperature. A common “B symptom” in certain lymphomas and leukemias.

- Unexplained Weight Loss: Significant weight loss without intentional dieting. Also a “B symptom” suggestive of malignancy.

- Generalized Weakness: A feeling of lack of physical strength or energy.

Symptoms Related to Reactive (Benign) Lymphocytosis

These symptoms are typically acute or subacute and often resolve as the underlying infection or condition clears.

Symptoms of Viral Infections (e.g., Infectious Mononucleosis from EBV, CMV)

- Sore Throat (Pharyngitis): Often severe, especially in mononucleosis.

- Swollen Lymph Nodes (Lymphadenopathy): Commonly in the neck (cervical), but can be generalized. They are usually tender to the touch.

- Enlarged Spleen (Splenomegaly): Can cause a feeling of fullness or discomfort in the left upper abdomen. Patients are often advised to avoid contact sports due to the risk of splenic rupture.

- Enlarged Liver (Hepatomegaly): Less common than splenomegaly but can occur.

- Rash: Maculopapular rash may occur, particularly if antibiotics like ampicillin or amoxicillin are given during EBV infection.

- Headache, Muscle Aches (Myalgia): General body aches.

Symptoms of Bacterial Infections (e.g., Pertussis)

- Severe, Prolonged Cough: In pertussis (“whooping cough”), this is the hallmark symptom, often with a characteristic “whooping” sound during inspiration. Vomiting after coughing fits is common.

- Signs of Chronic Infection (e.g., Tuberculosis, Brucellosis): Prolonged fever, night sweats, weight loss (which overlap with malignancy symptoms), cough (TB), joint pain (Brucellosis).

Symptoms of Stress/Trauma

Symptoms directly related to the acute stressor, such as pain from injury, symptoms of myocardial infarction, or seizure. Lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes) in these cases is usually transient and an incidental finding.

Drug Hypersensitivity

Skin rash, fever, eosinophilia, and sometimes organ involvement (e.g., liver, kidney) in conditions like DRESS syndrome.

Symptoms Related to Malignant Lymphocytosis (Lymphoproliferative Disorders)

These symptoms tend to be more chronic, persistent, and progressive. They often indicate the accumulation of abnormal lymphocytes in various organs.

- Swollen Lymph Nodes (Lymphadenopathy): Often generalized, firm, non-tender, and persistent (unlike the typically tender, resolving nodes in infections). Commonly in the neck, armpits (axillary), and groin (inguinal).

- Enlarged Spleen (Splenomegaly): Can be significant, causing abdominal fullness, discomfort, or early satiety due to pressure on the stomach. In some conditions like Hairy Cell Leukemia, massive splenomegaly is a hallmark.

- Enlarged Liver (Hepatomegaly): Due to infiltration by malignant cells.

- Recurrent Infections: Due to immune dysfunction (even with high lymphocyte counts, the cells may not function properly) or associated neutropenia.

- Bleeding or Bruising: If the bone marrow is significantly infiltrated by malignant lymphocytes, it can lead to suppression of normal blood cell production, resulting in:

- Anemia: Leading to pallor, shortness of breath, fatigue.

- Thrombocytopenia: Leading to easy bruising, petechiae, nosebleeds, or gum bleeding.

- Bone Pain: In cases of significant bone marrow involvement.

- Skin Lesions: In some T-cell lymphomas (e.g., Mycosis Fungoides/Sézary Syndrome), skin rashes, redness, itching, and scaling can be prominent.

- “B Symptoms”: Fever, drenching night sweats, and unexplained weight loss are highly suggestive of a lymphoproliferative disorder like lymphoma or leukemia.

- Less Common/Specific Symptoms:

- Hyperviscosity Syndrome: In extremely high lymphocyte counts (rarely seen in CLL), symptoms like headache, blurred vision, or confusion due to thickened blood.

- Peripheral Neuropathy: Can occur in some types of LGL leukemia or lymphoma.

- Autoimmune Phenomena: Autoimmune hemolytic anemia or immune thrombocytopenia can be associated with CLL.

Asymptomatic Lymphocytosis (High Lymphocytes)

It’s very common, especially in chronic conditions like CLL, for lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes) to be discovered incidentally during a routine complete blood count (CBC) ordered for other reasons. The patient may feel entirely well and have no noticeable symptoms. This highlights the importance of laboratory investigation in the diagnostic process.

Laboratory Investigations to Elucidate the Cause of Lymphocytosis

Laboratory investigations are fundamental to understanding the cause of lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes). They help differentiate between benign reactive conditions and potentially serious malignant disorders. The investigations proceed in a stepwise manner, becoming more specialized if initial tests suggest a more complex underlying issue.

Initial Screening Tests

These are typically the first tests ordered and provide essential preliminary information.

Complete Blood Count (CBC) with Differential

- Absolute Lymphocyte Count (ALC): Confirms the presence and magnitude of lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes) (e.g., > 4.0 x 109/L in adults).

- Other Cell Line Abnormalities:

- Anemia (low red blood cells/hemoglobin): Can suggest bone marrow infiltration by malignant cells or hemolysis (e.g., autoimmune hemolytic anemia complicating CLL).

- Thrombocytopenia (low platelets): Also suggests bone marrow infiltration or increased destruction (e.g., immune thrombocytopenia).

- Neutropenia (low neutrophils): Can occur in some infections or certain leukemias.

- Eosinophilia/Basophilia: May point to specific conditions (e.g., some parasitic infections, allergic reactions, or certain myeloproliferative neoplasms).

- Total White Blood Cell Count (WBC): The overall WBC count can range from mildly elevated to extremely high in lymphocytosis.

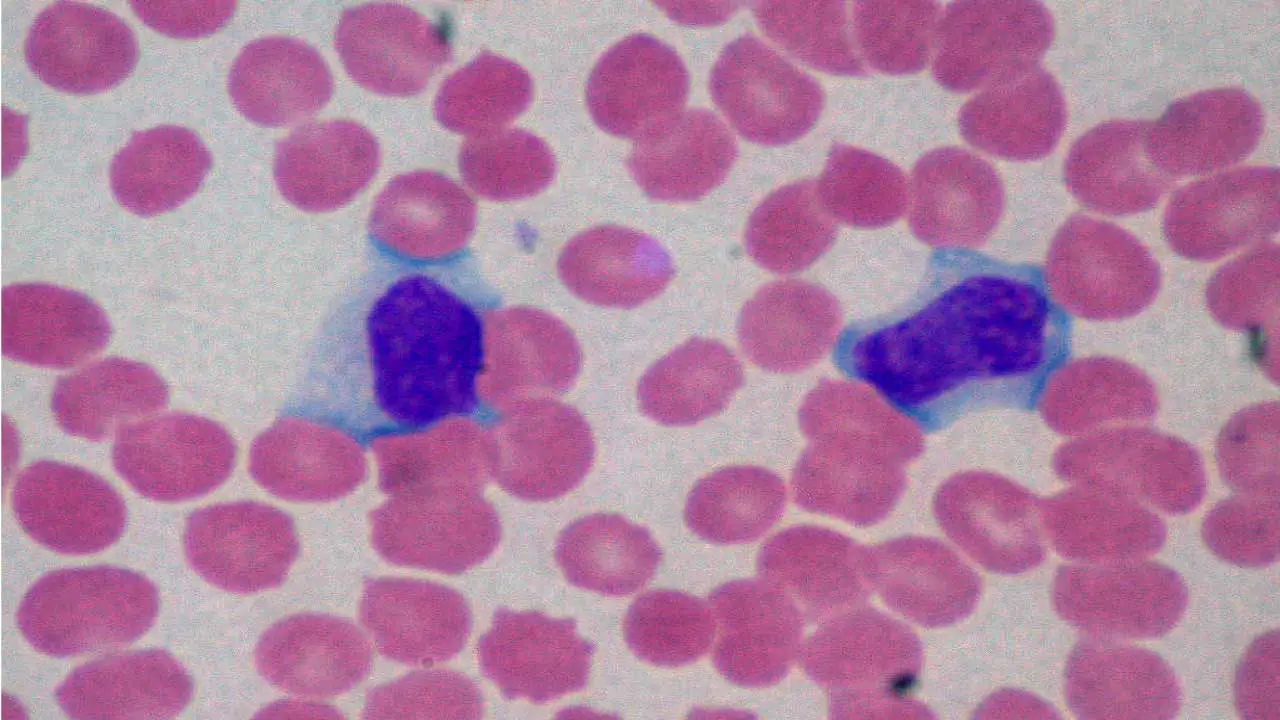

Peripheral Blood Smear (PBS) Examination

This allows for morphological assessment of the lymphocytes and other blood cells.

Key Morphological Findings

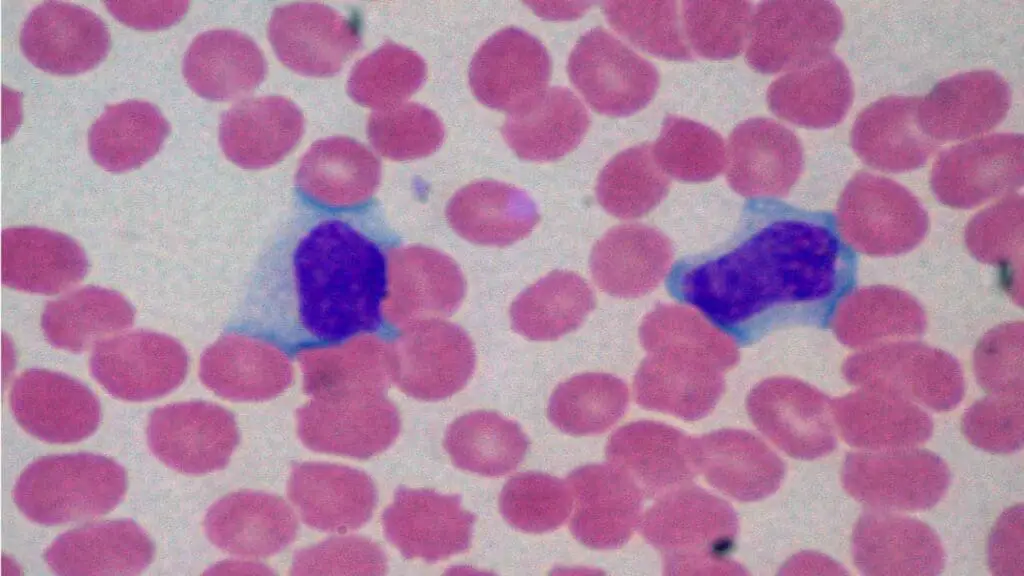

- Reactive/Atypical Lymphocytes: Often larger than normal lymphocytes, with abundant cytoplasm, irregular nuclei, and sometimes nucleoli. These are characteristic of acute viral infections (e.g., “Downey cells” in infectious mononucleosis). They appear pleomorphic (varied shapes and sizes).

- Small, Mature Lymphocytes: In conditions like Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL), lymphocytes appear small, with dense chromatin, scant cytoplasm, and often “smudge cells” (fragile lymphocytes that rupture during smear preparation). They are typically monotonous (look very similar to each other).

- Large Granular Lymphocytes (LGLs): Larger lymphocytes with prominent cytoplasmic granules, seen in LGL leukemia.

- Hairy Cells: Lymphocytes with fine, hair-like cytoplasmic projections, characteristic of Hairy Cell Leukemia.

- Prolymphocytes: Larger lymphocytes with prominent central nucleoli, seen in prolymphocytic leukemias (B-PLL, T-PLL).

- Lymphoblasts: Immature lymphocytes with high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, fine chromatin, and prominent nucleoli, seen in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

- Other Abnormalities: Presence of immature granulocytes, red blood cell morphology abnormalities (e.g., teardrop cells), or platelet abnormalities.

Targeted Investigations (Based on initial findings)

If the initial CBC and PBS suggest a specific etiology or raise suspicion for a malignant process, further, more specialized tests are ordered.

Serological Tests (for suspected infections)

- Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) Serology: Monospot test (heterophile antibody test) for rapid screening; specific EBV viral capsid antigen (VCA) IgM and IgG, EBNA (Epstein-Barr Nuclear Antigen) antibodies to confirm acute or past infection.

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Serology: CMV IgM and IgG antibodies.

- HIV Testing: HIV antigen/antibody combination tests, viral load.

- Hepatitis Viral Markers (HAV, HBV, HCV): To detect acute or chronic viral hepatitis.

- Other Infection-Specific Tests: Pertussis PCR/culture, Toxoplasma serology, Brucella titers, etc.

Immunophenotyping by Flow Cytometry

This is a crucial test for diagnosing and classifying lymphoproliferative disorders. It identifies specific surface markers (antigens, also called “clusters of differentiation” or CD markers) on the surface and inside lymphocytes. These markers help determine the lineage (B-cell, T-cell, NK-cell) and maturation stage of the cells, and crucially, detect clonality (whether the lymphocytes are derived from a single abnormal cell).

Key Applications

- Clonality Assessment: Detection of kappa or lambda light chain restriction in B cells indicates a monoclonal B-cell population, highly suggestive of a B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder. T-cell clonality is harder to prove by flow cytometry but can sometimes be inferred by aberrant marker expression or abnormal T-cell receptor (TCR) ratios (e.g., CD4:CD8 ratio).

- Diagnosis of CLL: Characteristically shows CD5+, CD19+, CD20 (dim), CD23+ on B cells.

- Differentiation from other B-cell Lymphomas: (e.g., Mantle Cell Lymphoma is CD5+, CD19+, CD20+, CD23-, Cyclin D1+).

- Diagnosis of T-cell/NK-cell Neoplasms: Specific markers help classify entities like T-LGL leukemia (CD3+, CD8+, CD16+, CD57+).

- Identifying Blasts: Detection of immaturity markers (e.g., CD34, TdT) helps diagnose acute leukemias (ALL).

Molecular and Cytogenetic Studies

These tests look for specific genetic abnormalities (chromosomal rearrangements, gene mutations) that are characteristic of certain lymphoproliferative disorders and provide important prognostic information, guiding treatment decisions.

- Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH): Uses fluorescent probes to detect specific chromosomal deletions, translocations, or gains. Examples in CLL: del(13q), trisomy 12, del(11q), and critically, del(17p) which indicates deletion of the TP53 gene and is associated with a poorer prognosis and resistance to certain therapies.

- Conventional Karyotyping: Analyzes the full set of chromosomes to detect larger structural or numerical abnormalities. Requires actively dividing cells.

- PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) and Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS):

- T-cell Receptor (TCR) and Immunoglobulin Heavy Chain (IGH) Gene Rearrangements: PCR-based clonality assays detect unique gene rearrangements in T cells and B cells, respectively, providing molecular evidence of a clonal lymphoid population. This is particularly useful for T-cell clonality as flow cytometry is less definitive.

- Mutation Analysis: Identifies specific gene mutations. Examples: BRAF V600E mutation in Hairy Cell Leukemia; TP53 mutations (often co-occurring with del(17p)), IGHV mutation status (mutated vs. unmutated, which is a key prognostic marker), NOTCH1, SF3B1 mutations in CLL.

Bone Marrow Aspiration and Biopsy

Performed when peripheral blood findings are inconclusive, to confirm the diagnosis of a lymphoproliferative disorder, or to stage the disease and assess the extent of bone marrow involvement.

Other Supportive and Prognostic Tests

- Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH): Often elevated in rapidly proliferating malignancies, serving as a general marker of tumor burden.

- Beta-2 Microglobulin: A protein found on the surface of most cells, elevated levels can indicate increased cell turnover or kidney dysfunction. It’s a prognostic marker in some lymphomas and leukemias (e.g., CLL).

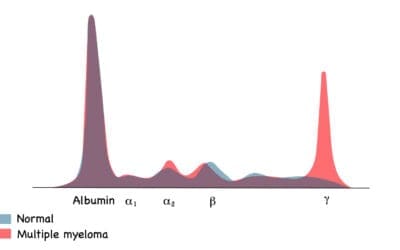

- Serum Protein Electrophoresis (SPEP) and Immunoglobulin Levels: To assess for monoclonal proteins (paraproteins) or hypogammaglobulinemia (low antibody levels, common in CLL and increasing infection risk).

- Coombs Test (Direct Antiglobulin Test): If autoimmune hemolytic anemia is suspected (e.g., in CLL patients with anemia).

- Imaging Studies (e.g., CT scan of neck, chest, abdomen, pelvis; PET-CT): Not directly laboratory tests, but crucial for assessing the extent of lymphadenopathy (swollen lymph nodes) and splenomegaly/hepatomegaly, which helps in staging lymphomas and leukemias.

General Treatment and Management of Lymphocytosis

The treatment and management of lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes) are entirely dependent on the underlying cause. Lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes) itself is a sign, not a disease, so the focus is always on addressing the condition leading to the elevated lymphocyte count.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Does lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes) lead to leukemia?

No, lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes) does not lead to leukemia.

This is a crucial point to clarify:

- Lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes) is a symptom or sign (a laboratory finding of an elevated lymphocyte count).

- Leukemia is a disease (a type of cancer of the blood and bone marrow).

Do high lymphocytes make you tired?

Yes, high lymphocytes can absolutely make you tired, although it’s usually not the lymphocytes themselves causing the fatigue directly, but rather the underlying condition that is leading to the lymphocytosis. Fatigue is a very common symptom associated with conditions that cause elevated lymphocyte counts.

Should I worry about high lymphocytes?

You should discuss high lymphocyte counts with a healthcare professional, as the significance of lymphocytosis varies greatly depending on the underlying cause.

While it’s frequently a benign and temporary response to common infections like viruses, indicating your immune system is actively fighting off an illness, it can also be a sign of more serious, chronic conditions or even certain blood cancers like leukemia or lymphoma.

Your doctor will consider the exact lymphocyte count, the presence of any other symptoms (like fever, fatigue, swollen lymph nodes), and the results of a peripheral blood smear and other targeted investigations to determine the cause and whether any further action or treatment is needed.

Can stress cause lymphocytosis?

Yes, stress, particularly acute severe stress, can indeed cause transient (temporary) lymphocytosis (high lympocytes). This phenomenon is often referred to as “transient stress lymphocytosis” (TSL).

How long does lymphocytosis last?

The duration of lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes) depends entirely on its underlying cause.

- Reactive Lymphocytosis (Most Common)

- Acute Infections (e.g., viral infections like mononucleosis, flu, or stress-induced): This type of lymphocytosis is usually transient and resolves within days to a few weeks, typically as the infection or acute stressor subsides. For instance, in severe acute stress, lymphocytosis can resolve within 24 to 48 hours. For viral infections, it might last up to a couple of months.

- Chronic Infections (e.g., tuberculosis, pertussis): In some persistent bacterial or parasitic infections, the lymphocytosis can linger for several weeks to months, reflecting the ongoing immune response.

- Post-Splenectomy: If lymphocytosis is due to the removal of the spleen, it can be a persistent, lifelong finding, as the spleen is no longer there to filter lymphocytes from the blood.

- Malignant Lymphocytosis (Lymphoproliferative Disorders)

- Chronic Conditions (e.g., Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia – CLL): In these cases, the lymphocytosis is a persistent, chronic feature of the disease itself. Without treatment, the lymphocyte count may continuously rise over months or years. Even with certain treatments (like BTK inhibitors), there can be a temporary increase in lymphocytes as they redistribute from tissues into the blood, which then typically resolves over several months (e.g., within 8-12 months with ibrutinib or acalabrutinib), but the underlying disease (and potential for future lymphocytosis) remains unless cured.

- Acute Leukemias (e.g., Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia – ALL): The high lymphocyte counts (blasts) are present until the disease is effectively treated with intensive chemotherapy, which typically induces a rapid decrease in the malignant cells.

Therefore, the duration can range from hours to days, weeks, months, or even be chronic, depending on whether it’s a transient reactive process or an ongoing malignant condition. Persistent lymphocytosis (high lymphocytes) (e.g., lasting more than 2-3 months) generally warrants further investigation to rule out a chronic underlying cause.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Hamad H, Mangla A. Lymphocytosis. [Updated 2023 Jul 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549819/

- Janeway CA Jr, Travers P, Walport M, et al. Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease. 5th edition. New York: Garland Science; 2001. Generation of lymphocytes in bone marrow and thymus. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK27123/

- Cano RLE, Lopera HDE. Introduction to T and B lymphocytes. In: Anaya JM, Shoenfeld Y, Rojas-Villarraga A, et al., editors. Autoimmunity: From Bench to Bedside [Internet]. Bogota (Colombia): El Rosario University Press; 2013 Jul 18. Chapter 5. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459471/

- https://ashpublications.org/thehematologist/article/doi/10.1182/hem.V22.2.2025210/535833/A-Hematopathologist-s-Approach-to-Atypical

- https://ashpublications.org/thehematologist/article/doi/10.1182/hem.V12.6.4507/462778/Diagnostic-Approach-to-Lymphocytosis

- Devi, A., Thielemans, L., Ladikou, E. E., Nandra, T. K., & Chevassut, T. (2022). Lymphocytosis and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: investigation and management. Clinical medicine (London, England), 22(3), 225–229. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmed.2022-0150