TL;DR

Cold Agglutinin Disease (CAD) is a form of autoimmune hemolytic anemia caused by IgM autoantibodies that agglutinate red blood cells at cold temperatures, leading to complement-mediated hemolysis.

- Causes ▾: It can be primary (idiopathic) or secondary to infections or lymphoproliferative disorders.

- Symptoms ▾: Acrocyanosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, and anemia.

- Diagnosis ▾: Positive DAT (C3d), elevated cold agglutinin titer, and thermal amplitude testing.

- Treatment ▾: Avoid cold, manage underlying causes, and immunosuppression (rituximab, complement inhibitors).

*Click ▾ for more information

Introduction

Cold agglutinin disease (CAD) represents a rare subtype of autoimmune hemolytic anemia, a condition characterized by the immune system’s erroneous production of autoantibodies that target and destroy the body’s own red blood cells (RBCs) .

What is autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA)?

AIHA is a condition in which the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks and destroys its own red blood cells (RBCs). This premature destruction of RBCs, known as hemolysis, leads to anemia, a deficiency of RBCs.

In essence, the immune system fails to recognize its own RBCs as “self” and treats them as foreign invaders.

Subtypes of AIHA

AIHA is broadly classified based on the temperature at which the autoantibodies react.

- Warm Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia (wAIHA)

This is the most common form of AIHA. The autoantibodies involved, typically IgG, react optimally at body temperature (37°C). Hemolysis is usually extravascular. It can be primary (idiopathic) or secondary to other conditions like autoimmune diseases, lymphomas, or certain medications. - Cold Agglutinin Disease (CAD)

In this subtype, the autoantibodies, primarily IgM, react optimally at temperatures below body temperature (typically 0-4°C). Hemolysis is often complement-mediated. Exposure to cold triggers RBC agglutination (clumping) and subsequent destruction.It can also be primary or secondary to infections or lymphoproliferative disorders. - Paroxysmal Cold Hemoglobinuria (PCH)

This is a less common form of cold-reacting AIHA. It involves an IgG autoantibody (the Donath-Landsteiner antibody) that binds to RBCs in cold temperatures and causes intravascular hemolysis upon warming. This condition is often associated with prior viral infections.

Pathophysiology of Cold Agglutinin Disease (CAD)

Cold agglutinins are autoantibodies, specifically of the immunoglobulin M (IgM) type, that have the unusual property of binding to red blood cells (RBCs) at temperatures below normal body temperature, typically below 37°C (86°F), with optimal activity observed between 0 and 5°C (32 and 41°F). This binding, or agglutination, causes the RBCs to clump together, impeding blood flow, particularly in the colder extremities such as fingers, toes, ears, and nose. Furthermore, the antibody-coated RBCs become targets for the complement system, a part of the immune system that leads to the premature destruction of these cells, a process known as hemolysis .

It is important to note that naturally occurring cold autoantibodies are present in almost all individuals. However, these natural antibodies exist at low concentrations, with titers typically less than 1:64 when measured at 4°C, and they do not exhibit activity at higher temperatures . In contrast, individuals with CAD produce pathologic cold agglutinins at significantly elevated titers, often exceeding 1:1000, and these antibodies can react at warmer temperatures, ranging from 28 to 31°C and sometimes even at 37°C . This difference in thermal reactivity and concentration is a critical factor distinguishing CAD from a benign laboratory finding.

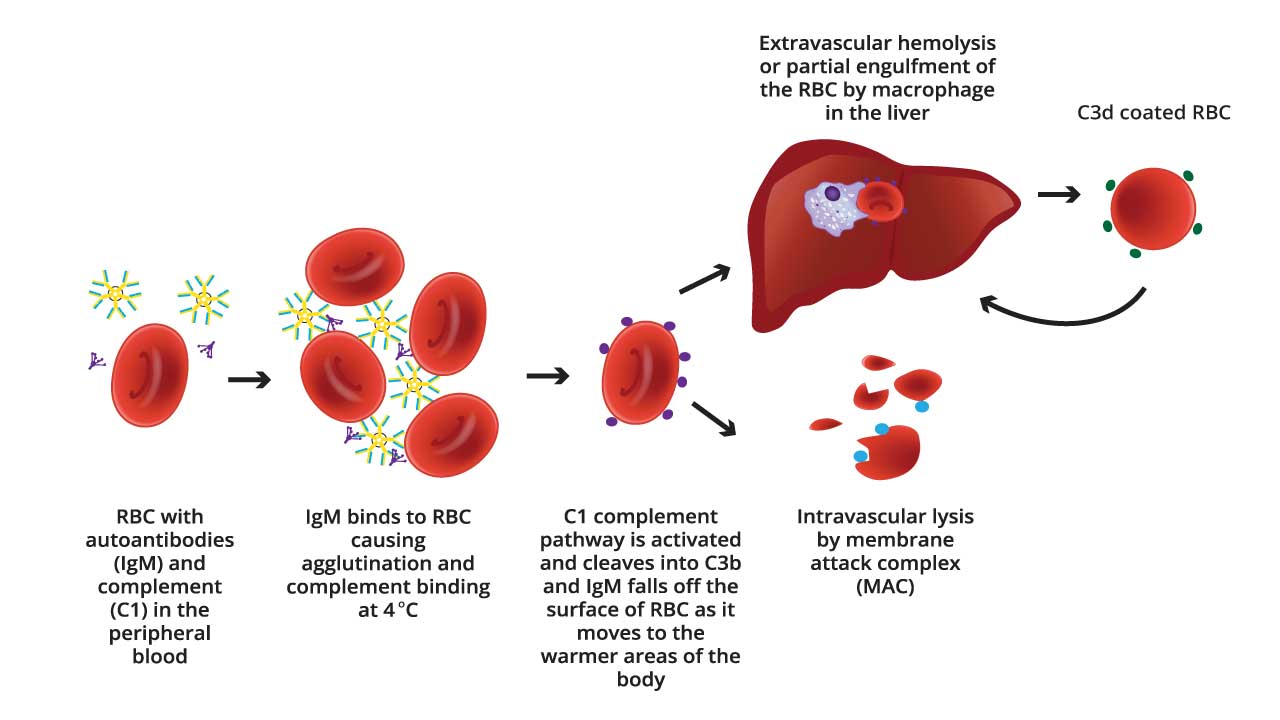

Mechanism of RBC Agglutination and Complement Activation

Complement-mediated hemolysis contributes significantly to the anemia seen in CAD. The detection of C3d on RBCs by the direct antiglobulin test (DAT/Coombs test) is a key diagnostic finding in CAD. The consumption of complement proteins during this process can lead to decreased serum complement levels, especially C4.

Red Blood Cell Agglutination

- IgM Binding: The process begins with the cold agglutinin, an IgM antibody, binding to antigens on the surface of RBCs. These antigens are often I/i antigens, which are carbohydrate structures present on RBC membranes. This binding occurs most efficiently at lower temperatures, typically below 30°C, and especially at 0-4°C.

- Agglutination: IgM is a large pentameric molecule, meaning it has five binding sites. This structure allows it to bind to multiple RBCs simultaneously. As the IgM antibodies bind to RBCs, they effectively bridge the cells together, forming clumps or aggregates. This clumping is known as agglutination. The degree of agglutination is dependent on the titer of the cold agglutinins, and the temperature.

- Consequences: In vivo, this agglutination can lead to sludging of blood in small blood vessels, particularly in the extremities where temperatures are lower. This can cause acrocyanosis (blue discoloration of fingers, toes, ears, and nose) and impaired blood flow resulting in potential tissue damage. In laboratory settings, the agglutination interferes with accurate red blood cell counts and other hematological parameters.

Complement Activation

- Complement Cascade: Once the IgM antibody is bound to the RBC surface, it can activate the classical pathway of the complement system. The complement system is a series of proteins that enhance the immune response. C1q, a component of the complement system, binds to the IgM antibody that is attached to the red blood cell. This sets off a cascade of complement protein activation (C1, C4, C2, and C3).

- C3 Activation and Deposition: A crucial step is the activation of C3, which leads to the deposition of C3b and C3d fragments on the RBC surface. C3d, in particular, remains bound to the RBC membrane even after the IgM antibody detaches as the blood warms.

- Hemolysis: The complement activation can lead to:

- Extravascular hemolysis: C3b can act as an opsonin, marking the RBC for destruction by macrophages in the spleen.

- Intravascular hemolysis: In some cases, the complement cascade proceeds to the formation of the membrane attack complex (MAC), which creates pores in the RBC membrane, causing it to lyse (burst) within the bloodstream.

What causes Cold Agglutinin Disease?

Cold agglutinin disease can manifest in two primary forms: primary and secondary.

Primary (Idiopathic) Cold Agglutinin Disease

Primary cold agglutinin disease, also termed idiopathic CAD, occurs without any identifiable underlying cause. This form is frequently linked to the production of monoclonal IgM autoantibodies, often displaying kappa light chains.

The source of these antibodies is often a subtle clonal lymphoproliferative disorder, characterized by an increased and uncontrolled proliferation of B lymphocytes within the bone marrow . Although this represents a clonal expansion of lymphocytes, it may not always meet the criteria for an overt malignancy.

Primary CAD predominantly affects adults, typically emerging after the age of 50, with the highest incidence observed in individuals in their 70s and 80s. The connection between this seemingly benign lymphoproliferation and the development of pathogenic autoantibodies underscores the intricate nature of immune system regulation.

Secondary Cold Agglutinin Disease

Secondary cold agglutinin disease develops as a consequence of another underlying health issue, which can include infections, autoimmune disorders, or malignancies.

In this form, the cold-reacting autoantibodies can be either monoclonal or polyclonal. A wide array of infectious agents has been implicated in triggering secondary CAD. The diverse range of these infectious agents suggests that the immune response to various pathogens can, in susceptible individuals, lead to the production of cold agglutinins, possibly through mechanisms like molecular mimicry where microbial antigens share similarities with RBC antigens.

Viral infections commonly associated with this condition include:

- Infectious mononucleosis caused by the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae (a frequent cause of atypical pneumonia)

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV)

- Influenza

- Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

- Rubella, varicella, mumps, hepatitis C, adenovirus, parvovirus B19, and even SARS-CoV-2.

Bacterial infections linked to secondary CAD encompass:

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae

- Legionnaires’ disease

- Syphilis

- Listeriosis

- Escherichia coli

- Subacute bacterial endocarditis .

Parasitic infections such as malaria and trypanosomiasis (Chagas disease) have also been reported in association with secondary cold agglutinin disease.

Beyond infections, several underlying conditions can contribute to the development of secondary cold agglutinin disease.

Lymphoproliferative disorders:

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)

- Waldenström macroglobulinemia

- Multiple myeloma

- Kaposi sarcoma

- Angioimmunoblastic lymphoma

Autoimmune diseases:

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Systemic sclerosis (scleroderma), have also been implicated

Other less common associations:

- CANOMAD syndrome

- Hyperreactive malarial splenomegaly (HMS)

- Certain chromosomal abnormalities like trisomy 3 and 12

Clinical Presentation and Symptoms

The clinical presentation of cold agglutinin disease encompasses a range of symptoms primarily stemming from anemia and impaired blood circulation due to cold-induced RBC agglutination and subsequent hemolysis .

- Acrocyanosis: Discoloration of extremities (fingers, toes, ears, nose) upon cold exposure. A hallmark of cold agglutinin disease.

- Raynaud’s phenomenon: Cold, numb sensation and a loss of color in the fingers or toes upon cold exposure.

- Hemolytic anemia symptoms: Fatigue, weakness, pallor, dyspnea, tachycardia, jaundice (if significant hemolysis), hematuria and splenomegaly.

- Cold-induced symptoms: Livedo reticularis, a net-like, purplish discoloration of the skin, and in severe cases, skin ulcers on the extremities of the digits may develop and cold urticaria.

- Potential complications: Thromboembolic events and severe anemia.

Laboratory Investigation of Cold Agglutinin Disease

The diagnosis of cold agglutinin disease relies on a combination of clinical findings and specific laboratory investigations.

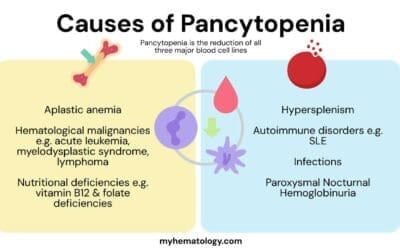

Complete blood count (CBC)

Expected findings are anemia and reticulocytosis. The mean corpuscular volume (MCV) may be elevated due to the presence of reticulocytosis and the agglutination of RBCs.

During episodes of active hemolysis, an increase in white blood cells (leukocytosis) might also be evident. To avoid interference from cold agglutinins, it is often necessary to repeat the CBC after warming the blood sample to 37°C.

Direct antiglobulin test (DAT/Coombs test)

The direct antiglobulin test (DAT), also known as the Coombs test, is essential for diagnosing autoimmune hemolytic anemia.

In cold agglutinin disease, the DAT is typically positive for the complement component C3d, a key diagnostic criterion for CAD, indicating the deposition of complement proteins on the surface of red blood cells, a consequence of autoantibody binding. In some cases, a weak positive reaction for IgG may also be observed (in up to 22% of patients).

It is crucial to ensure proper handling of blood samples for the DAT. Blood should be drawn into pre-warmed containers and maintained at 37-38°C until the serum or plasma is separated. This is to prevent the cold agglutinins from binding to the RBCs in vitro, which could lead to a false-negative result.

Cold agglutinin titer

The cold agglutinin titer is a specific test that measures the concentration of cold agglutinins in the patient’s serum.

The test involves serially diluting the patient’s serum and adding it to a standardized suspension of normal red blood cells at a temperature of 4°C. The highest dilution of the patient’s serum at which agglutination (clumping) of the red blood cells is observed is reported as the titer.

A titer of 1:64 or greater at 4°C is generally considered abnormal. However, clinically significant cold agglutinin disease with hemolytic anemia is typically associated with much higher titers, often exceeding 1:1000.

In some instances, cold agglutinin titers may also be determined at warmer temperatures, such as 30°C and 37°C, to assess the thermal amplitude of the antibodies.

Similar to the DAT, proper handling of blood samples is essential for an accurate cold agglutinin titer. The blood must be kept warm (37-38°C) from the time of collection until the serum is separated to prevent the cold agglutinins from binding to the patient’s own red blood cells in the sample, which would lead to a falsely low or negative titer.

The cold agglutinin titer is a direct measure of the autoantibodies responsible for the disease, and the level often correlates with the severity of the condition.

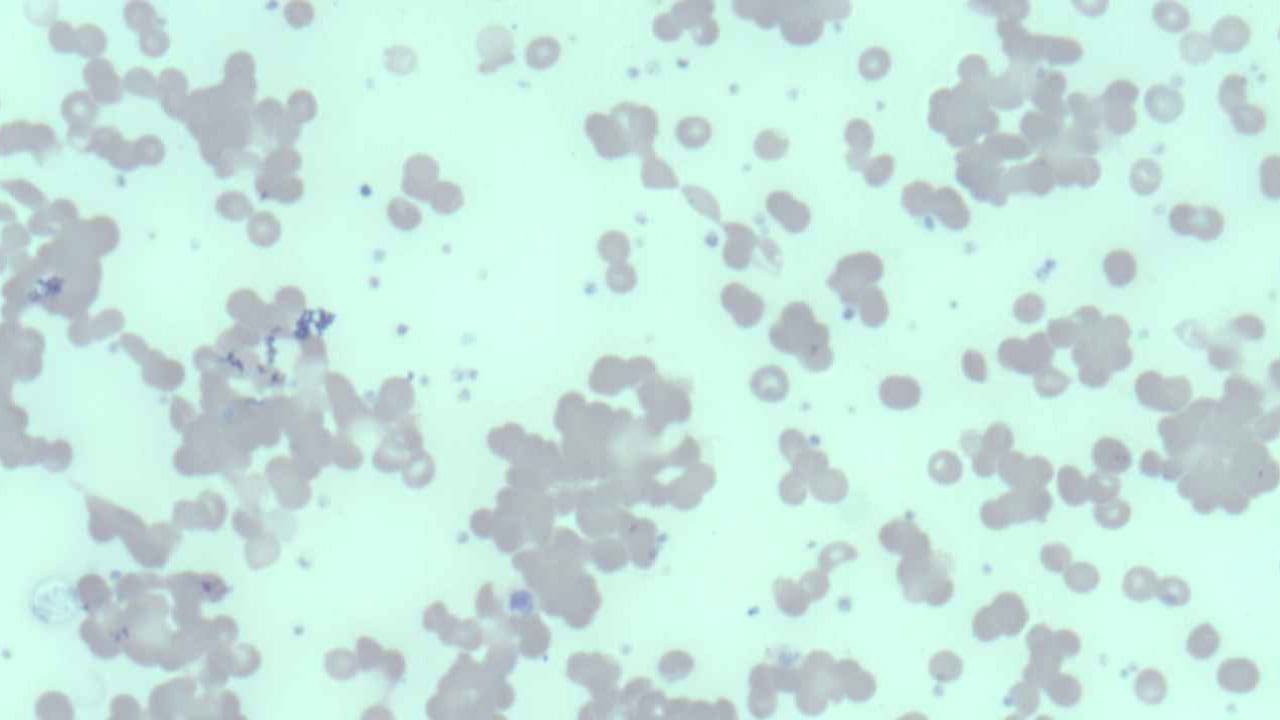

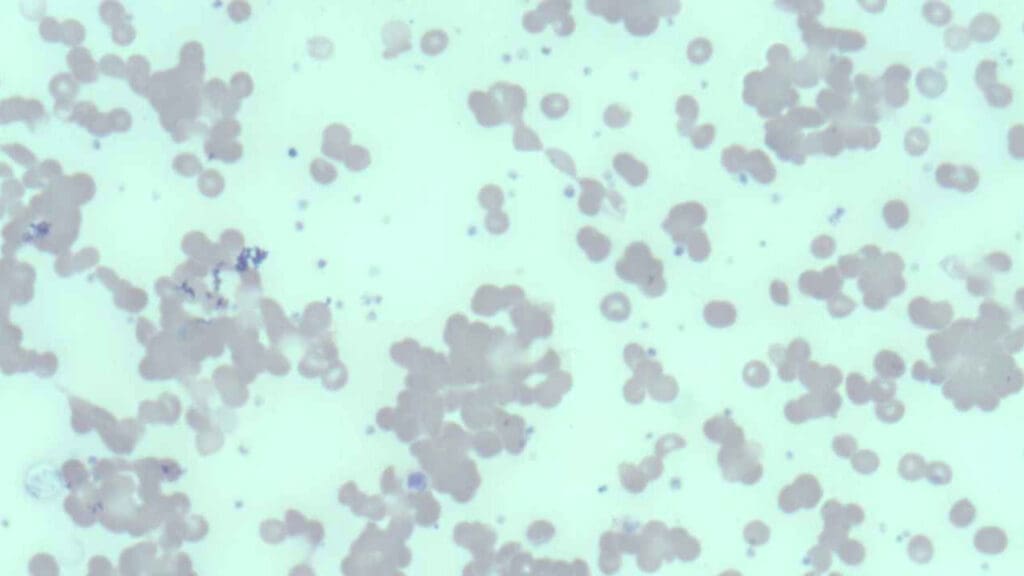

Peripheral blood smear

Examination of the peripheral blood smear under a microscope can reveal characteristic clumps of red blood cells, particularly if the blood sample has been exposed to cold temperatures. Spherocytes, abnormally shaped red blood cells, may also be observed on the smear.

The reticulocyte count, which measures the number of immature red blood cells, is usually increased as the bone marrow attempts to compensate for the premature destruction of RBCs . Polychromasia, a variation in the color of red blood cells, may also be noted on the peripheral smear, reflecting the increased presence of these immature cells.

These initial findings strongly suggest hemolytic anemia and point towards agglutination as a potential underlying mechanism, warranting further specific testing for cold agglutinins.

Complement levels

Complement testing measures the levels of complement proteins in the patient’s serum. It assesses the overall activity and consumption of the complement system. This involves laboratory assays that quantify the levels of specific complement components, such as C3 and C4. In cold agglutinin disease, due to the activation of the complement cascade, there may be decreased levels of these complement proteins, indicating that they are being consumed.

Thermal amplitude test

The primary purpose of the thermal amplitude test is to determine the temperature range at which cold agglutinins (the autoantibodies involved in CAD) react with red blood cells (RBCs). It determines the highest temperature at which the cold agglutinins in the patient’s serum will react with red blood cells .

While cold agglutinins typically exhibit optimal activity at 4°C, some may retain reactivity at temperatures closer to normal body temperature. A broader thermal amplitude, meaning the antibodies are active at higher temperatures, is often associated with more significant hemolysis and more pronounced clinical symptoms .

This test can help differentiate clinically relevant cold agglutinin disease from cases where cold agglutinins are only active at very low temperatures and may not cause significant hemolysis in vivo.

Biochemical tests

Evidence of hemolysis can be further substantiated by assessing specific biochemical markers in the blood.

- Total and indirect bilirubin: Often elevated due to the breakdown of hemoglobin released from destroyed red blood cells

- Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels: Increased as LDH is an enzyme released from damaged cells, including red blood cells undergoing hemolysis

- Haptoglobin levels: Decreased as during hemolysis, the increased release of hemoglobin leads to a greater consumption of haptoglobin

Investigations to identify underlying causes

- Serological tests for infections (Mycoplasma, EBV, etc.).

- Immunoglobulin electrophoresis (for monoclonal gammopathy).

- Bone marrow biopsy (if suspicion of lymphoproliferative disorder).

- Flow cytometry to identify any abnormal monoclonal populations of lymphocytes.

A comprehensive diagnostic approach to cold agglutinin disease involves not only confirming the presence of cold agglutinins and hemolysis but also diligently investigating any potential underlying conditions, especially in cases of suspected secondary CAD.

Differential Diagnosis of Cold Agglutinin Disease

Differential diagnosis is crucial in Cold Agglutinin Disease (CAD) to ensure accurate diagnosis and appropriate management.

Paroxysmal Cold Hemoglobinuria (PCH)

PCH involves an IgG autoantibody (the Donath-Landsteiner antibody), not IgM. PCH causes intravascular hemolysis upon warming after cold exposure, leading to hemoglobinuria. The DAT in PCH is often positive for complement but may be negative for IgG. PCH is often associated with recent viral infections.

Key Difference:

- The Donath-Landsteiner test is specific for PCH.

- Hemoglobinuria is a prominent feature of PCH, unlike CAD.

Other Causes of Hemolytic Anemia

- Warm Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia (wAIHA): wAIHA involves IgG autoantibodies that react optimally at body temperature. The DAT in wAIHA is typically positive for IgG and/or complement. wAIHA is not triggered by cold exposure.

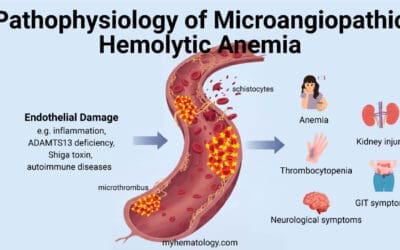

- Other Causes of Hemolysis: Hereditary spherocytosis, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency, and other inherited hemolytic anemias. These conditions have distinct clinical and laboratory features. Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA) which can be caused by TTP, HUS, DIC, and HELLP syndrome.

Other Causes of Acrocyanosis and Raynaud’s Phenomenon

- Primary Raynaud’s Phenomenon: This is a benign condition characterized by vasospasm in response to cold or stress. It lacks the hemolytic anemia and complement activation seen in cold agglutinin disease. It also lacks the red cell agglutination.

- Secondary Raynaud’s Phenomenon: This can be associated with connective tissue diseases (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus, scleroderma). These conditions have distinct clinical and serological features.

- Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD): PAD involves narrowing of peripheral arteries, leading to reduced blood flow. It typically causes pain and claudication, not hemolytic anemia.

Other causes of cold induced urticaria

Cold induced urticaria, is a condition where hives appear after cold exposure. This condition does not include the hemolytic anemia associated with CAD.

Treatment and Management of Cold Agglutinin Disease

The management of cold agglutinin disease encompasses both non-pharmacological and pharmacological approaches, with the primary goals of alleviating symptoms, preventing complications, and addressing any underlying causes. Non-pharmacological measures are used typically for milder cases while pharmacological treatment is generally considered for patients who experience persistent and bothersome symptoms, particularly anemia, despite adhering to cold avoidance measures .

Avoidance of cold exposure

Avoidance of cold temperatures is paramount . This includes wearing warm clothing, especially gloves, socks, and head coverings, even in moderately cool environments . Patients should be advised to avoid prolonged exposure to cold weather, air conditioning, and cold water. Some individuals may also benefit from avoiding cold foods and beverages.

Supportive care

Supportive measures include maintaining a healthy lifestyle with a balanced diet rich in folic acid (found in fresh fruits and vegetables), ensuring adequate rest, and engaging in physical activities that are less strenuous, especially for those with anemia.

In cases of severe, acute anemia, blood transfusions may be necessary to increase the red blood cell count and alleviate symptoms. It is essential to warm the blood during transfusion to prevent exacerbation of agglutination, and crossmatching should be performed at 37°C.

Transfusion of complement-rich blood products like plasma should be avoided if possible. Plasma exchange, or plasmapheresis, can be used as a temporary measure to remove cold agglutinins from the circulation, particularly in acute situations or before surgical procedures that require hypothermia . However, the effect of plasma exchange is often short-lived as the production of IgM antibodies continues.

Treatment of underlying causes

- Antibiotics for infections.

- Chemotherapy or immunotherapy for lymphoproliferative disorders.

Immunosuppressive therapy

Rituximab, a monoclonal antibody that targets the CD20 protein on B lymphocytes, is often used as a first-line therapy to reduce the production of cold agglutinins. It can be administered as monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy agents like bendamustine or fludarabine. While response rates to rituximab monotherapy are around 50%, complete responses are rare. Combination therapies may offer higher efficacy but can also be associated with increased toxicity.

Novel therapies

Sutimlimab is a complement inhibitor that selectively targets and inhibits C1s, a protein in the complement pathway, thereby preventing complement-mediated hemolysis. It has been approved by regulatory authorities for reducing the need for red blood cell transfusions in adults with cold agglutinin disease and can provide a rapid clinical response, often used in patients who have not responded to other treatments or in emergency situations.

Other emerging therapies include eculizumab, another complement inhibitor targeting the terminal complement pathway; bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor; and daratumumab, an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody, which may be considered in refractory cases or specific clinical scenarios

It is important to note that corticosteroids are generally ineffective in treating IgM-mediated CAD and are not recommended as a primary treatment. Similarly, splenectomy is typically not beneficial in cold agglutinin disease.

The choice of pharmacological treatment depends on various factors, including the severity of symptoms, the presence of underlying conditions, and the patient’s overall health status.

Prognosis & Long-Term Management

Cold avoidance: Consistent avoidance of cold temperatures in all aspects of daily life is crucial for minimizing symptoms and improving quality of life. This includes being mindful of ambient temperatures, dressing warmly in layers, and taking precautions when handling cold objects or consuming cold foods and drinks. Strict adherence to cold avoidance measures is key to minimizing episodes of hemolysis and circulatory symptoms. Preventing cold-induced complications is a primary goal of long-term management.

Healthy lifestyle: Maintaining overall health through a balanced diet, ensuring sufficient rest, and engaging in appropriate physical activity as tolerated are also important supportive measures.

Regular monitoring: Regular follow-up appointments with a hematologist are essential for ongoing monitoring of the disease, adjusting treatment strategies as needed, and managing any potential complications that may arise.

Promptly addressing any infections is also important, as infections can sometimes trigger exacerbations of cold agglutinin disease.

It is crucial for patients to inform their medical team about their cold agglutinin diagnosis, especially during procedures like blood draws or intravenous infusions, to ensure that blood samples and intravenous fluids are kept warm .

Long-term monitoring involves regular blood tests to track hemoglobin levels, markers of hemolysis, and cold agglutinin titers to assess the effectiveness of the management plan and detect any signs of disease progression.

While cold agglutinin disease is a chronic condition for many individuals, it is reassuring to note that it does not typically appear to significantly reduce life expectancy, especially with appropriate management and adherence to recommended strategies .

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Does cold agglutinin affect hemoglobin?

Yes, cold agglutinins significantly affect hemoglobin levels. Cold agglutinins, primarily IgM antibodies, cause hemolytic anemia in Cold Agglutinin Disease (CAD) by binding to red blood cells (RBCs) at low temperatures, leading to agglutination and complement activation. This results in premature RBC destruction, either in the spleen or bloodstream, consequently lowering hemoglobin levels and causing anemia symptoms like fatigue, weakness, pallor, and dyspnea, which are confirmed by laboratory findings of low hemoglobin and elevated reticulocyte counts.

Does cold agglutinin affect platelets?

While the primary target of cold agglutinins is red blood cells (RBCs), their effect on platelets is generally considered to be minimal and indirect. Cold agglutinins primarily cause hemolytic anemia, and they do not directly cause significant platelet destruction or dysfunction.

Does cold agglutinin affect ESR?

Cold agglutinins can significantly elevate the Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) because the clumping of red blood cells (RBCs) caused by these antibodies makes them settle faster in the ESR test, leading to an artificially high reading. This interference means that ESR results in patients with Cold Agglutinin Disease (CAD) must be interpreted cautiously, and alternative inflammatory markers like CRP may be more reliable.

Can cold agglutinin cause blood clots?

Cold agglutinins can increase the risk of blood clots by causing red blood cell (RBC) agglutination, which leads to sludging and thickening of the blood, particularly in small vessels exposed to cold, thus impeding blood flow and promoting thrombus formation. Additionally, complement activation associated with CAD can damage endothelial cells, further contributing to the risk of thromboembolic events like deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, especially in patients with high cold agglutinin titers and significant cold-induced agglutination.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Swiecicki P, Hegerova LT, Gertz MA. Cold agglutinin disease. Blood 2013; 122(7):1114-1121.

- Berentsen S. New Insights in the Pathogenesis and Therapy of Cold Agglutinin-Mediated Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia. Front Immunol. 2020 Apr 7;11:590. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00590. PMID: 32318071; PMCID: PMC7154122.

- Berentsen S, Barcellini W, D’Sa S, Randen U, Tvedt THA, Fattizzo B, Haukås E, Kell M, Brudevold R, Dahm AEA, Dalgaard J, Frøen H, Hallstensen RF, Jæger PH, Hjorth-Hansen H, Małecka A, Oksman M, Rolke J, Sekhar M, Sørbø JH, Tjønnfjord E, Tsykunova G, Tjønnfjord GE. Cold agglutinin disease revisited: a multinational, observational study of 232 patients. Blood. 2020 Jul 23;136(4):480-488. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020005674. PMID: 32374875.

- Guenther A, Tierens A, Malecka A, Delabie J. The Histopathology of Cold Agglutinin Disease-Associated B-Cell Lymphoproliferative Disease. Am J Clin Pathol. 2023 Sep 1;160(3):229-237. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqad048. PMID: 37253147.

- Berentsen S. How I treat cold agglutinin disease. Blood. 2021 Mar 11;137(10):1295-1303. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019003809. PMID: 33512410.

- Broome CM. Complement-directed therapy for cold agglutinin disease: sutimlimab. Expert Rev Hematol. 2023 Jul-Dec;16(7):479-494. doi: 10.1080/17474086.2023.2218611. Epub 2023 Jun 2. PMID: 37256550.

- Gelbenegger G, Berentsen S, Jilma B. Monoclonal antibodies for treatment of cold agglutinin disease. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2023 May;23(5):395-406. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2023.2209265. Epub 2023 May 15. PMID: 37128907.