TL;DR

Lymphadenopathy refers to the swelling or enlargement of lymph nodes, which are part of the lymphatic system, a crucial component of the immune system.

Causes of Lymphadenopathy ▾: The causes are diverse, with infections being the most common, followed by malignancies, autoimmune disorders, drug reactions, and less frequent conditions.

Symptoms and Signs ▾: Lymphadenopathy can manifest with local symptoms like swelling, tenderness, and redness, or systemic symptoms such as fever, weight loss, and night sweats, indicating a broader underlying disease.

Diagnosis of Lymphadenopathy ▾: Diagnosis involves a thorough physical examination, detailed patient history, laboratory tests, imaging studies, and often a lymph node biopsy to determine the underlying cause.

Treatment and Management ▾: Management focuses on treating the root cause, which may involve antibiotics, antiviral medications, antifungal drugs, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or immunosuppressants. Symptomatic relief and observation are also part of the management.

Potential Complications ▾: Untreated lymphadenopathy can lead to complications like the spread of infection, metastasis of cancer, progressive organ damage in autoimmune diseases, and chronic lymphedema.

*Click ▾ for more information

Introduction

The term lymphadenopathy literally means “disease of the lymph nodes,” but in practice, it refers to the swelling or enlargement of one or more lymph nodes.

What are Lymph Nodes?

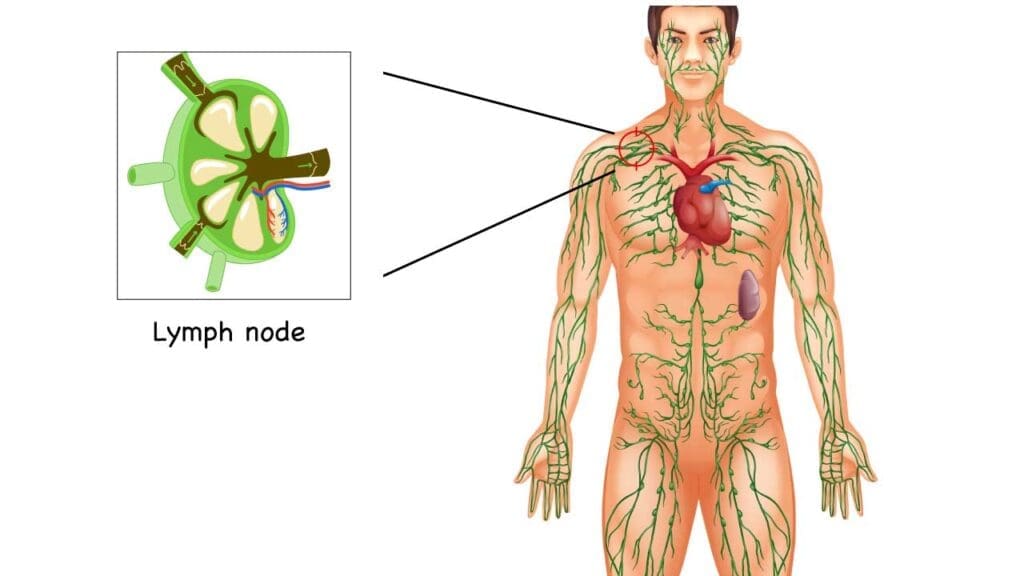

Imagine a network of tiny but crucial filtering stations scattered throughout the body, particularly concentrated in areas like the neck, armpits, and groin. These are lymph nodes, small, bean-shaped organs that are a vital part of the lymphatic system.

Think of the lymphatic system as a parallel drainage and defense network to the blood circulatory system. Instead of blood, it carries a fluid called lymph, which contains waste products, cellular debris, and importantly, immune cells, including lymphocytes (B cells and T cells) and antigen-presenting cells like dendritic cells.

Importance of Lymph Nodes in the Immune System

Lymph nodes are indispensable hubs for immune surveillance and response. They act as strategic meeting points where immune cells congregate and interact. As lymph fluid circulates through these nodes, several critical processes occur.

- Filtration: Lymph nodes filter the lymph, trapping pathogens (like bacteria and viruses), cellular debris, and even cancer cells that may be present in the tissues. This prevents the widespread dissemination of these harmful substances throughout the body.

- Antigen Presentation: This is where cells like dendritic cells (DCs) play a crucial role. DCs are antigen-presenting cells that reside in tissues throughout the body. When they encounter pathogens or abnormal cells, they engulf and process them, breaking them down into smaller fragments called antigens. These DCs then migrate through the lymphatic vessels to the lymph nodes. Within the lymph nodes, they present these processed antigens on their surface to T lymphocytes (T cells). This “antigen presentation” is the critical first step in initiating an adaptive immune response.

- Activation of Adaptive Immunity: The presentation of antigens by DCs to specific T cells in the lymph nodes leads to the activation and proliferation of these T cells. Depending on the type of antigen and the signals received, these activated T cells can differentiate into various effector cells, such as cytotoxic T cells (which kill infected or cancerous cells) or helper T cells (which help activate other immune cells like B cells).

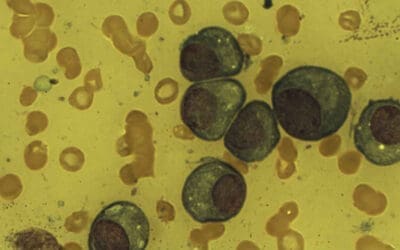

- Antibody Production: Lymph nodes are also sites where B lymphocytes (B cells) reside. When B cells encounter their specific antigens (either directly or presented by helper T cells), they become activated and differentiate into plasma cells. Plasma cells are antibody-producing factories that secrete large amounts of antibodies into the lymph and blood, targeting the specific pathogen or antigen.

What is Lympadenopathy?

When lymph nodes become larger than their normal size (typically less than 1 cm, though this can vary by location), it signifies that there’s an increased activity or a problem within the node or the region it drains. This enlargement which is also known as lymphadenopathy is usually a sign that the body is responding to some form of challenge.

Think of it this way: if a particular area of the body is fighting an infection, the lymph nodes in that drainage area will become more active. This increased activity involves the proliferation of immune cells to combat the infection and the trapping of pathogens and cellular debris. This surge in cellular activity and the accumulation of these substances cause the lymph node to swell.

Similarly, in cases of malignancy, cancer cells can either originate within the lymph node (lymphoma) or spread to the lymph node from a primary tumor elsewhere in the body (metastasis), leading to its enlargement. Inflammatory and autoimmune conditions can also trigger an immune response that involves lymph node enlargement.

Therefore, while enlarged lymph nodes are a common finding, they are an important clinical sign that warrants investigation to determine the underlying cause. The size, location, consistency, and associated symptoms of the enlarged nodes can provide valuable clues to the diagnosis.

How to Evaluate Lymphadenopathy

| Feature | Description | Potential Significance |

| Size | Diameter of the lymph node (e.g., <1 cm, 1-2 cm, >2 cm). Note variations by location (inguinal nodes can be slightly larger normally). | – Cervical lymph nodes larger than 1 cm are considered enlarged. – Axillary lymph nodes larger than 1 cm are typically considered enlarged. – Inguinal lymph nodes up to 1.5-2 cm can be normal in some individuals due to drainage from the lower extremities, but larger nodes warrant investigation. – Palpable supraclavicular lymph nodes (above the collarbone) are almost always abnormal and highly concerning for malignancy. – Larger size (>2 cm, especially in supraclavicular region) raises suspicion for malignancy or significant infection. Smaller enlargement is common in localized infections. |

| Consistency | How the node feels upon palpation (e.g., soft, firm, rubbery, hard, shotty). | – Soft and compressible: Often benign (e.g., viral infection). – Firm: Can be benign or malignant. – Rubbery: Suggestive of lymphoma. – Hard/Stony: Raises concern for metastatic malignancy. – Shotty (small, hard, mobile): Can be normal or post-infection. |

| Tenderness | Presence or absence of pain upon palpation. | – Tender (painful): Suggests inflammation or infection. – Non-tender: Can be seen in both benign and malignant conditions (e.g., lymphoma, metastasis). |

| Mobility | How easily the node moves when palpated (e.g., freely mobile, limited mobility, fixed). | – Freely mobile: More likely benign. – Limited mobility or fixed (matted to other nodes or underlying tissue): Raises suspicion for malignancy or significant inflammation/fibrosis. |

| Number/Distribution | Single node enlargement vs. multiple nodes; localized (one region) vs. generalized (two or more non-contiguous regions). | – Localized: Often related to local infection or inflammation in the drainage area. – Generalized: Suggests systemic illness (e.g., widespread infection, autoimmune disorder, systemic malignancy). |

| Overlying Skin | Appearance of the skin over the enlarged node (e.g., normal, erythematous/red, warm, draining sinus). | – Erythema and warmth: Suggest local infection (lymphadenitis). – Draining sinus: May indicate tuberculosis or other chronic infections. |

| Duration | How long the lymph node enlargement has been present (acute: days to weeks; chronic: weeks to months). | – Acute: Typically associated with infections. – Chronic: Can be seen in chronic infections, autoimmune diseases, or indolent malignancies. – Persistent, unexplained lymphadenopathy warrants further investigation. |

| Associated Symptoms | Systemic symptoms accompanying lymphadenopathy (e.g., fever, night sweats, weight loss (B symptoms), fatigue, rash, joint pain). | Systemic symptoms can provide crucial clues to the underlying etiology (e.g., B symptoms suggest lymphoma or certain infections; rash and joint pain suggest autoimmune disease). |

| Location | Anatomical site(s) where lymphadenopathy is present (e.g., cervical, axillary, inguinal, supraclavicular). | Certain locations are more concerning than others (e.g., supraclavicular). The location can also point towards the likely drainage area of an infection or malignancy. |

Causes of Lymphadenopathy

Lymphadenopathy is a common clinical finding with a broad range of underlying causes, spanning from self-limiting infections to serious malignancies. Understanding these causes is crucial for accurate diagnosis and appropriate management.

Infections (The Most Frequent Culprits)

Infections are by far the most common reason for lymph node enlargement. The body’s immune response to pathogens often involves the proliferation of lymphocytes and macrophages within the draining lymph nodes.

Viral Infections

Viruses frequently cause lymphadenopathy, often generalized or affecting regional nodes near the site of infection.

- Upper Respiratory Infections (URIs): Common colds and sore throats can lead to tender cervical lymphadenopathy.

- Infectious Mononucleosis (EBV): Characterized by significant, often generalized lymphadenopathy, particularly in the posterior cervical region, along with fatigue, fever, and pharyngitis.

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV): Can cause generalized lymphadenopathy, often accompanied by fatigue and fever, especially in immunocompromised individuals.

- Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV): Localized lymphadenopathy can occur with primary oral or genital herpes infections.

- Varicella-Zoster Virus (VZV): Chickenpox and shingles can cause regional lymphadenopathy in the affected dermatome.

- Measles, Mumps, Rubella (MMR): These childhood viral illnesses can present with generalized lymphadenopathy.

- HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus): Generalized lymphadenopathy is common in primary HIV infection and can persist in later stages.

Bacterial Infections

Bacterial infections can cause localized or regional lymphadenopathy, often with signs of inflammation in the affected area.

- Streptococcal Pharyngitis (“Strep Throat”): Leads to tender anterior cervical lymphadenopathy.

- Skin and Soft Tissue Infections (e.g., Cellulitis, Abscesses): Cause regional lymphadenopathy draining the infected site.

- Cat Scratch Disease (Bartonella henselae): Typically presents with localized, often tender lymphadenopathy near the site of a cat scratch or bite.

- Tuberculosis (TB): Can cause localized (e.g., cervical, known as scrofula) or generalized lymphadenopathy. Nodes may be firm, matted, and can sometimes undergo caseation necrosis and form draining sinuses.

- Syphilis (Treponema pallidum): Primary syphilis is associated with painless regional lymphadenopathy near the site of the chancre. Secondary syphilis can cause generalized lymphadenopathy.

- Brucellosis: A zoonotic infection that can cause generalized lymphadenopathy, fever, and other systemic symptoms.

Fungal Infections

Fungal infections are less common causes of lymphadenopathy but should be considered, especially in immunocompromised individuals or those with relevant travel history.

- Histoplasmosis, Coccidioidomycosis, Blastomycosis: These systemic mycoses can cause regional or generalized lymphadenopathy, often associated with pulmonary symptoms. The specific presentation can vary depending on the geographic prevalence of these fungi.

Parasitic Infections

Certain parasitic infections can also lead to lymphadenopathy.

- Toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma gondii): Can cause localized (often cervical) or generalized lymphadenopathy, sometimes accompanied by fatigue and mild flu-like symptoms.

- Leishmaniasis: Depending on the form (cutaneous or visceral), localized or generalized lymphadenopathy can occur, often with other characteristic skin lesions or systemic symptoms.

- Filariasis: Can cause lymphadenopathy, particularly in the inguinal and femoral regions, potentially leading to lymphedema in chronic cases.

Malignancies

Lymphadenopathy can be a sign of primary hematologic malignancies or metastatic solid tumors.

- Primary Lymphoid Malignancies: These cancers originate in the lymphatic system itself.

- Lymphomas (Hodgkin and Non-Hodgkin): Often present with painless, persistent lymphadenopathy, which can be localized or generalized. Systemic symptoms (B symptoms: fever, night sweats, weight loss) may also be present. The consistency of the nodes can be firm or rubbery.

- Leukemias: While primarily affecting the bone marrow and blood, some leukemias (e.g., chronic lymphocytic leukemia – CLL) can also cause significant lymphadenopathy.

- Metastatic Solid Tumors: Cancer cells from a primary tumor elsewhere in the body can spread to regional lymph nodes. The characteristics of the involved nodes often include being hard, irregular, and potentially fixed to surrounding tissues. The location of the lymphadenopathy can provide clues to the primary cancer site (e.g., cervical lymphadenopathy with metastasis from head and neck cancers; axillary lymphadenopathy with metastasis from breast cancer).

Autoimmune and Inflammatory Conditions

Various autoimmune and inflammatory disorders can lead to lymph node enlargement due to immune system activation.

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE): Can cause generalized lymphadenopathy as part of its systemic inflammation.

- Rheumatoid Arthritis: Generalized or regional lymphadenopathy can occur, particularly in association with active disease.

- Sarcoidosis: Characterized by the formation of granulomas (clusters of inflammatory cells) in various organs, including lymph nodes, leading to lymphadenopathy (often hilar and mediastinal, but peripheral nodes can also be involved).

- Kawasaki Disease: A childhood vasculitis that presents with fever, rash, and cervical lymphadenopathy (often unilateral).

- Connective Tissue Diseases: Other conditions like Sjögren’s syndrome and dermatomyositis can sometimes be associated with lymphadenopathy.

Drug Reactions

Certain medications can trigger an immune response leading to lymphadenopathy. This is a less common cause but important to consider in the differential diagnosis. Examples include:

- Phenytoin (an anti-seizure medication)

- Allopurinol (used for gout)

- Sulfonamides (antibiotics)

- Certain vaccines can cause transient, localized lymphadenopathy.

Less Common Causes

A variety of less frequent conditions can also cause lymphadenopathy.

- Storage Diseases: Lysosomal storage diseases (e.g., Gaucher disease, Niemann-Pick disease) can lead to lymph node enlargement due to the accumulation of metabolic products.

- Amyloidosis: Deposition of amyloid protein can occur in lymph nodes, causing enlargement.

- Silicone Implants: Regional lymphadenopathy has been reported in some individuals with silicone breast implants.

- Idiopathic Lymphadenopathy: In some cases, the cause of lymphadenopathy remains unclear even after thorough investigation.

Signs and Symptoms Associated with Lymphadenopathy

The presentation of lymphadenopathy can range from an isolated, asymptomatic finding to a prominent feature of a systemic illness. A thorough understanding of the local and systemic symptoms associated with enlarged lymph nodes is crucial for guiding the diagnostic process.

Local Symptoms Directly Related to Enlarged Lymph Nodes

These symptoms arise from the physical presence and sometimes the inflammatory processes within the enlarged lymph node(s).

- Palpable Lump or Swelling: This is the most common and often the first noticed sign. Patients may feel a “swollen gland” in the neck, armpit, or groin. The size can vary from barely palpable to several centimeters.

- Tenderness and Pain: Enlarged lymph nodes, particularly those caused by infection or inflammation (lymphadenitis), are often tender to the touch and can be spontaneously painful. The degree of tenderness can range from mild discomfort to severe pain.

- Warmth: Inflamed lymph nodes due to infection can feel warmer to the touch compared to the surrounding tissues. This is due to increased blood flow to the area as part of the inflammatory response.

- Redness (Erythema): The skin overlying an infected lymph node may become red and inflamed. This is another sign of local inflammation and potential infection within or around the node.

- Difficulty Swallowing or Breathing: Enlarged lymph nodes in the neck (cervical lymphadenopathy), especially if large or multiple, can sometimes compress surrounding structures, leading to difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) or, less commonly, difficulty breathing (dyspnea).

- Local Symptoms Related to the Affected Area: If the lymphadenopathy is secondary to a local infection, patients may also experience symptoms related to the primary site of infection, such as:

- Sore throat with cervical lymphadenopathy.

- Skin rash or wound with regional lymphadenopathy.

- Ear pain with preauricular or cervical lymphadenopathy.

Systemic Symptoms Suggesting an Underlying Systemic Condition

These symptoms are not directly caused by the enlarged lymph nodes themselves but rather by the underlying systemic illness responsible for the lymphadenopathy. Their presence can provide crucial clues to the etiology.

- Fever: Elevated body temperature can accompany infections (viral, bacterial, fungal), some autoimmune diseases, and certain malignancies (often as a “B symptom”).

- Night Sweats: Episodes of profuse sweating during sleep, often drenching the bedclothes, can be a significant “B symptom” suggestive of lymphoma, tuberculosis, or certain other infections.

- Unexplained Weight Loss: Significant and unintentional weight loss (typically more than 10% of body weight over 6 months) is another important “B symptom” that can indicate malignancy or chronic infections like TB or HIV.

- Fatigue and Malaise: Feeling unusually tired and unwell can be associated with a wide range of conditions causing lymphadenopathy, including infections, autoimmune diseases, and malignancies.

- Rash: The presence and characteristics of a skin rash can be helpful in diagnosing viral infections (e.g., measles, rubella), autoimmune diseases (e.g., SLE), or drug reactions causing lymphadenopathy.

- Joint Pain (Arthralgia) or Swelling (Arthritis): These symptoms may suggest an underlying autoimmune or inflammatory condition.

- Sore Throat (Pharyngitis): Often associated with viral or bacterial infections causing cervical lymphadenopathy.

- Cough: May be present with respiratory infections or certain malignancies like lymphoma involving the chest.

- Abdominal Pain or Distension: Can occur with lymphadenopathy in the abdomen (mesenteric or retroperitoneal) due to infection, inflammation, or malignancy.

- Headache: May be associated with certain infections or systemic illnesses.

The Importance of History Taking

A detailed history from the patient is paramount in evaluating lymphadenopathy. Key aspects to explore include:

- Onset and Duration: When did the swelling first appear? Has it been acute or gradual? Has it persisted or fluctuated?

- Associated Symptoms: Are there any local symptoms (pain, redness) or systemic symptoms (fever, weight loss, fatigue)?

- Past Medical History: Any history of recent infections, autoimmune diseases, malignancies, or exposure to tuberculosis?

- Medication History: Any new medications started recently?

- Travel History: Recent travel to areas endemic for certain infections (e.g., malaria, leishmaniasis)?

- Exposure History: Contact with sick individuals, animals (e.g., cats for cat scratch disease), or potential environmental exposures?

- Social History: Risk factors for HIV or other infections?

Physical Examination of Lymph Nodes

As discussed earlier, careful palpation of the lymph nodes is crucial. Pay attention to:

- Location: Where are the enlarged nodes located?

- Size: What is the approximate diameter of the nodes?

- Consistency: How do they feel (soft, firm, rubbery, hard)?

- Tenderness: Are they painful to touch?

- Mobility: Can they be easily moved, or are they fixed?

- Number: Are there single or multiple enlarged nodes? Are they matted together?

- Overlying Skin: Is there any redness, warmth, or drainage?

Physical Examination of Adjacent Areas

When you encounter lymphadenopathy, it’s essential not to focus solely on the enlarged nodes themselves. A thorough examination of the areas that drain into those nodes is equally important.

Primary Infection

If the lymphadenopathy is due to an infection, there’s often a primary site of infection in the region drained by the affected lymph nodes. You should carefully examine these areas for:

- Skin and Soft Tissue: Look for cuts, abrasions, insect bites, rashes (erythematous, vesicular, pustular), cellulitis (redness, warmth, swelling, tenderness), abscesses (localized collection of pus), or signs of fungal infections (e.g., scaling, discoloration). For example, axillary lymphadenopathy might be associated with a skin infection on the arm or hand. Inguinal lymphadenopathy could be linked to a foot infection or a sexually transmitted infection with lesions in the genital area.

- Head and Neck: For cervical lymphadenopathy, examine the throat for pharyngitis or tonsillitis (redness, exudates), the ears for otitis externa or media (tenderness, discharge), the scalp for infections, and the oral cavity for ulcers or dental infections. Preauricular lymphadenopathy might be associated with conjunctivitis or eye infections.

- Other Regions: Depending on the location of the enlarged nodes, examine the corresponding drainage areas. For instance, epitrochlear lymphadenopathy (near the elbow) can be associated with infections of the forearm or hand.

Primary Malignancy

Lymph nodes can become enlarged due to metastasis from a primary cancer in their drainage area. Therefore, when evaluating lymphadenopathy, especially if it’s suspicious (hard, fixed, non-tender), you should also examine the adjacent regions for any signs of a primary tumor.

- Head and Neck: In cases of cervical lymphadenopathy, carefully examine the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, thyroid gland, and scalp for any masses, ulcers, or asymmetry.

- Breast: Axillary lymphadenopathy is a common sign of breast cancer metastasis. A thorough breast examination, including palpation for lumps, skin changes (peau d’orange, retraction), and nipple discharge, is crucial.

- Lungs: Supraclavicular lymphadenopathy, particularly on the left side (Virchow’s node), can be a sign of metastatic lung cancer or abdominal cancers. A chest examination for abnormal breath sounds or signs of a mass is important.

- Abdomen and Pelvis: Inguinal lymphadenopathy can be associated with malignancies of the lower extremities, genitalia, anus, or even some pelvic cancers. Abdominal and pelvic examinations for masses or organomegaly might be indicated.

- Skin: Lymph nodes can also be involved in primary skin cancers like melanoma or squamous cell carcinoma. Examine the skin in the drainage area for suspicious moles or lesions.

Laboratory Investigations Related to Lympadenopathy

The choice of laboratory investigations for lymphadenopathy depends heavily on the clinical presentation, the characteristics of the enlarged lymph nodes, and the patient’s medical history and risk factors. Investigations can range from basic blood tests to specialized serological assays and molecular studies.

Basic Blood Tests: Initial Screening and Assessment

These are often the first-line investigations to assess the patient’s overall health and look for general signs of infection, inflammation, or hematological abnormalities.

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) with Differential

- White Blood Cell (WBC) Count: Elevated WBC count (leukocytosis) can suggest infection. A low WBC count (leukopenia) might be seen in certain viral infections or bone marrow disorders.

- Differential Count: The proportions of different types of WBCs (neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils) can provide clues. For example, lymphocytosis (increased lymphocytes) is common in viral infections like infectious mononucleosis or chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Neutrophilia (increased neutrophils) often points towards bacterial infections. Eosinophilia (increased eosinophils) might suggest parasitic infections or allergic reactions.

- Hemoglobin and Hematocrit: To assess for anemia, which can be associated with chronic infections, malignancies, or autoimmune diseases.

- Platelet Count: To evaluate for thrombocytopenia (low platelets), which can occur in certain infections, autoimmune disorders, or hematological malignancies.

- Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) and C-Reactive Protein (CRP): These are non-specific markers of inflammation in the body. Elevated levels can be seen in infections, autoimmune diseases, and some malignancies. While not specific to the cause of lymphadenopathy, they can indicate the presence of an inflammatory process.

- Liver Function Tests (LFTs): Elevated liver enzymes (e.g., ALT, AST, bilirubin) can be seen in certain viral infections (like EBV or CMV), some medications causing lymphadenopathy, or in cases of liver involvement by malignancy or granulomatous diseases like sarcoidosis.

- Renal Function Tests (RFTs): Assessing kidney function (e.g., creatinine, urea) is important for overall patient evaluation and to rule out kidney involvement in systemic illnesses.

Serological Tests: Identifying Specific Infections and Autoimmune Markers

These tests look for antibodies or antigens related to specific infectious agents or autoimmune diseases. They are usually ordered based on the clinical suspicion raised by the history and physical examination.

- Infectious Mononucleosis Panel: Tests for antibodies against Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV), including heterophile antibodies (Monospot test) and specific EBV antigens (VCA IgM, VCA IgG, EBNA IgG).

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Serology: Tests for CMV IgM and IgG antibodies, which can indicate recent or past infection.

- HIV Testing: Antibody tests (ELISA, rapid tests) followed by confirmatory tests (Western blot or PCR) if indicated, especially in patients with risk factors or suggestive clinical findings.

- Hepatitis Serology: Tests for Hepatitis B and C viruses (surface antigen, antibodies, viral load if positive) may be relevant in cases of generalized lymphadenopathy or abnormal LFTs.

- Streptococcal Antibody Tests: Anti-streptolysin O (ASO) titer or anti-DNase B antibodies might be ordered if there’s a suspicion of post-streptococcal complications.

- Cat Scratch Disease Serology: Antibody tests for Bartonella henselae can be helpful in suspected cases.

- Tuberculosis Tests: Tuberculin skin test (TST) or Interferon-Gamma Release Assays (IGRAs) like QuantiFERON-TB Gold can be used to assess for latent TB infection. Sputum or tissue samples can be sent for acid-fast bacilli (AFB) smear and culture if active TB is suspected.

- Syphilis Serology: Rapid plasma reagin (RPR) or Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) tests, followed by confirmatory tests (e.g., FTA-ABS or TPPA) if reactive.

- Toxoplasmosis Serology: IgG and IgM antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii can help determine if there’s a recent or past infection.

- Autoantibody Testing: If an autoimmune etiology is suspected based on clinical features, tests like Antinuclear Antibody (ANA), Rheumatoid Factor (RF), anti-dsDNA antibodies, anti-Sm antibodies, and others may be ordered.

Specialised Blood Tests

These tests are usually reserved for more complex or suspected cases.

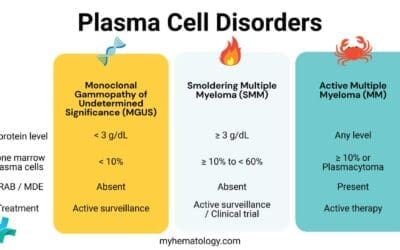

- Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH): Elevated levels can be seen in lymphomas, leukemias, and other conditions with rapid cell turnover.

- Beta-2 Microglobulin: Can be elevated in some lymphomas and other hematological malignancies.

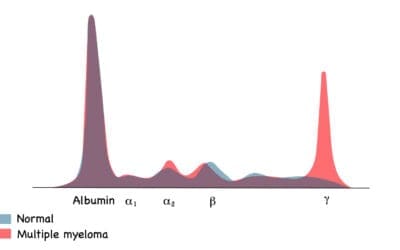

- Serum Immunoglobulin Levels: May be abnormal in certain lymphomas, multiple myeloma, and some autoimmune disorders.

- Flow Cytometry: Analysis of blood or lymph node samples to identify specific cell populations and surface markers, crucial in diagnosing leukemias and lymphomas.

- Molecular Studies (e.g., PCR for specific pathogens or genetic mutations): Can be used to detect specific infectious agents (e.g., EBV DNA, CMV DNA, HIV RNA) or genetic abnormalities associated with hematological malignancies.

Imaging Studies (When Indicated)

Imaging studies are valuable tools to visualize lymph nodes that may not be easily palpable (e.g., mediastinal, abdominal, pelvic) and to assess their characteristics and relationship to surrounding structures. They also help in identifying potential primary malignancies or other associated findings.

- Ultrasound: Often the first-line imaging modality for superficial lymph nodes (neck, axilla, groin). It’s readily available, non-invasive, and relatively inexpensive. Ultrasound can help determine the size, shape, and internal architecture of lymph nodes (e.g., presence of a hilum, cortical thickness, vascularity on Doppler). It can also guide fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsies.

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: Provides cross-sectional images of the body using X-rays. CT is excellent for visualizing deeper lymph nodes in the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. It can assess the size, number, and distribution of enlarged nodes and identify associated organomegaly, masses, or other abnormalities. CT is often used for staging malignancies and evaluating for internal lymphadenopathy.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Uses magnetic fields and radio waves to create detailed images of soft tissues. MRI can be useful in specific cases, such as evaluating lymphadenopathy in the head and neck region, particularly when assessing for local invasion by tumors. It can also provide more detailed information about the internal structure of lymph nodes in certain situations.

- Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Scan: A functional imaging technique that uses a radioactive tracer (usually fluorodeoxyglucose, FDG) to detect areas of high metabolic activity, which can indicate malignancy or inflammation. PET scans are particularly useful in staging lymphomas and certain other cancers, as well as identifying metabolically active lymph nodes that may not appear significantly enlarged on CT or MRI. Often combined with CT (PET-CT) for precise anatomical localization of the areas of increased metabolic activity.

Lymph Node Biopsy: The Definitive Diagnostic Tool

Ultimately, a lymph node biopsy is often required to establish a definitive diagnosis, especially when malignancy or certain granulomatous diseases are suspected, or when the cause remains unclear after initial blood tests and imaging. The choice of biopsy method (core needle biopsy, or excisional biopsy) depends on the clinical scenario and the suspected diagnosis. Histopathological examination of the biopsied tissue, often with immunohistochemical staining and molecular studies, provides crucial information about the underlying pathology.

Treatment and Management

The primary goal in managing lymphadenopathy is to identify and treat the underlying condition. Simply treating the enlarged lymph nodes themselves without addressing the etiology is generally not appropriate, except for symptomatic relief in some cases.

Addressing the Underlying Cause

- Infections

- Bacterial Infections: Treated with appropriate antibiotics targeting the specific bacteria identified or suspected. The duration of treatment depends on the type and severity of the infection. Lymph node size usually decreases as the infection resolves. In cases of abscess formation within a lymph node, drainage (either by needle aspiration or surgical incision) may be necessary in addition to antibiotics.

- Viral Infections: Most viral infections causing lymphadenopathy are self-limiting and do not require specific antiviral treatment (e.g., common cold). Symptomatic relief (e.g., rest, fluids, pain relievers) is usually sufficient. For specific viral infections like herpes simplex or varicella-zoster, antiviral medications may be indicated. HIV infection is managed with antiretroviral therapy (ART), which can help control viral load and improve immune function, often leading to a reduction in lymphadenopathy.

- Fungal Infections: Systemic antifungal medications are used to treat fungal infections causing lymphadenopathy. The specific drug and duration depend on the type of fungus and the extent of the infection.

- Parasitic Infections: Antiparasitic medications are used to treat parasitic infections like toxoplasmosis or leishmaniasis. The choice of drug depends on the specific parasite.

- Tuberculosis: Treated with a multi-drug regimen of antibiotics for a prolonged period (typically 6-9 months) under strict medical supervision.

- Malignancies

- Lymphomas (Hodgkin and Non-Hodgkin): Treatment depends on the type and stage of lymphoma and may include chemotherapy, radiation therapy, immunotherapy, targeted therapy, or stem cell transplantation. Management is highly specialized and individualized.

- Leukemias: Treatment also depends on the type of leukemia and may involve chemotherapy, radiation therapy, targeted therapy, and stem cell transplantation.

- Metastatic Solid Tumors: Management focuses on treating the primary cancer and may involve surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, hormonal therapy, targeted therapy, or immunotherapy. Lymph node involvement is often considered in the staging and prognosis of the cancer.

- Autoimmune and Inflammatory Conditions: Treatment aims to suppress the underlying autoimmune or inflammatory response. This may involve medications such as corticosteroids, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) like methotrexate, biologics (e.g., TNF-alpha inhibitors), or other immunosuppressants. The management is tailored to the specific autoimmune disease.

- Drug Reactions: The primary management involves identifying and discontinuing the offending medication. Lymphadenopathy usually resolves gradually after the drug is stopped. Symptomatic relief may be provided in the interim.

- Less Common Causes: Treatment is directed at the specific underlying condition (e.g., management of storage diseases, amyloidosis).

Symptomatic Relief: Managing Discomfort

While addressing the underlying cause is paramount, symptomatic measures can help alleviate discomfort associated with lymphadenopathy.

- Pain Management: Over-the-counter pain relievers like nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or acetaminophen can help reduce pain and inflammation in tender lymph nodes. Stronger analgesics may be required in some cases.

- Warm Compresses: Applying warm compresses to the affected area can sometimes help reduce pain and swelling associated with inflammatory or infectious lymphadenopathy.

Observation (“Watchful Waiting”)

In certain situations, particularly with localized, small, non-tender lymphadenopathy that is likely due to a mild viral infection and without any concerning systemic symptoms, a period of observation with close follow-up may be appropriate. If the lymph nodes do not resolve or worsen over a few weeks, further investigation is warranted.

When to Refer to a Specialist

It’s crucial to understand when referral to a specialist is necessary. Key indicators for referral include:

- Persistent Generalized Lymphadenopathy: Enlargement of lymph nodes in multiple areas without a clear benign cause.

- Suspicious Clinical Features: Hard, fixed, rapidly enlarging, or matted lymph nodes.

- Presence of B Symptoms: Fever, night sweats, unexplained weight loss.

- Supraclavicular Lymphadenopathy: Enlargement of nodes above the collarbone is often associated with malignancy.

- Lack of Resolution: Lymphadenopathy that persists or worsens despite treatment for a presumed benign cause (e.g., antibiotics for a suspected bacterial infection).

- Abnormal Laboratory or Imaging Findings: Results that suggest a serious underlying condition.

- Lymphadenopathy in the Absence of an Obvious Local Infection.

Specialists who may be involved in the management of lymphadenopathy include:

- Hematologist/Oncologist: For suspected or confirmed hematological malignancies or metastatic disease.

- Infectious Disease Specialist: For complex or unusual infections causing lymphadenopathy.

- Rheumatologist: For lymphadenopathy associated with autoimmune or inflammatory conditions.

- Surgeon: For lymph node biopsies or drainage of abscesses.

Potential Complications of Untreated Lymphadenopathy

The complications of untreated lymphadenopathy are largely dependent on the underlying etiology. Ignoring enlarged lymph nodes, especially if they are persistent or associated with concerning symptoms, can lead to a variety of adverse outcomes.

Complications Related to Untreated Infections

- Progression of Local Infection: If bacterial infections causing lymphadenitis are not treated with antibiotics, the infection can worsen and spread to surrounding tissues, leading to cellulitis, abscess formation (a localized collection of pus that may require drainage), or even sepsis (a life-threatening systemic inflammatory response).

- Spread of Systemic Infections: Untreated viral, fungal, or parasitic infections can disseminate throughout the body, leading to more severe organ involvement and potentially life-threatening conditions. For example, untreated tuberculosis can spread to the lungs, bones, brain, and other organs. Untreated HIV infection progresses to AIDS, with severe immunodeficiency and opportunistic infections.

- Post-Infectious Complications: Some infections, like streptococcal pharyngitis, if left untreated, can lead to serious sequelae such as rheumatic fever or glomerulonephritis. The persistent immune activation in the lymph nodes might contribute to these complications.

Complications Related to Untreated Malignancies

- Disease Progression and Metastasis: Untreated lymphomas and leukemias will continue to proliferate and spread to other lymph nodes, bone marrow, and organs, leading to organ dysfunction, bone pain, anemia, increased susceptibility to infections, and ultimately, death. Untreated metastatic cancers will also continue to grow and spread, causing local invasion, distant metastases, and significant morbidity.

- Local Compression: Mass effect from enlarged cancerous lymph nodes can compress vital structures, such as blood vessels, nerves, or airways, leading to pain, swelling, neurological deficits, or breathing difficulties.

- Paraneoplastic Syndromes: Some cancers can produce substances that cause systemic symptoms not directly related to the tumor itself, such as hypercalcemia, SIADH (syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion), or neurological syndromes.

Complications Related to Untreated Autoimmune and Inflammatory Conditions

- Progressive Organ Damage: Untreated autoimmune diseases like SLE or rheumatoid arthritis can lead to chronic inflammation and damage in various organs, including joints, kidneys, heart, lungs, and brain, resulting in significant disability and reduced life expectancy. The persistent lymphadenopathy reflects ongoing immune system dysregulation.

- Increased Risk of Lymphoma: Some autoimmune conditions, such as Sjögren’s syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis, are associated with an increased risk of developing lymphoma. Chronic inflammation and immune activation in the lymph nodes may play a role in this increased risk.

- Systemic Inflammatory Effects: Uncontrolled inflammation from autoimmune diseases can have widespread effects on the body, contributing to fatigue, pain, and other systemic symptoms.

Other Potential Complications

- Chronic Lymphedema: In some cases, persistent inflammation or obstruction of lymphatic drainage due to untreated lymphadenopathy (especially if caused by infection or malignancy) can lead to chronic swelling (lymphedema) in the affected limb or area. This can cause discomfort, skin changes, and an increased risk of infection.

- Psychological Distress: Persistent and unexplained lymphadenopathy can cause anxiety and distress for patients, especially if they are concerned about a serious underlying condition.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

When to worry about swollen lymph nodes?

It’s important to seek medical attention if you experience swollen lymph nodes accompanied by any of the following concerning signs and symptoms.

General Worrisome Signs

- Nodes that are hard or rubbery to the touch. Unlike the softer feel of nodes swollen due to infection, these may indicate a more serious underlying issue.

- Nodes that are fixed and don’t move when you gently push on them.

- Nodes that continue to enlarge or have been present for more than two to four weeks without any apparent reason (like a resolving cold).

- Swollen lymph nodes near the collarbone (supraclavicular). These are often more concerning.

- Unexplained and persistent generalized lymphadenopathy, meaning swelling in two or more areas of the body.

Accompanying Symptoms that Raise Concern

- Persistent fever or recurrent fevers.

- Night sweats, especially drenching sweats.

- Unexplained weight loss.

- Fatigue that is persistent and severe.

- Easy bruising or bleeding.

- Difficulty swallowing or breathing (seek immediate medical care).

- Red or inflamed skin over the swollen lymph node.

Factors that Increase Concern

- Older age (over 40) when a new, unexplained lymph node appears.

- No obvious source of infection to explain the swelling.

- Personal history of cancer.

While swollen lymph nodes are most commonly a sign that your body is fighting off a routine infection, the presence of these “red flag” symptoms warrants a prompt evaluation by a healthcare professional to determine the underlying cause and ensure timely management. Don’t hesitate to seek medical advice if you are worried about your swollen lymph nodes.

At what size is a lymph node considered cancerous?

It’s important to understand that there is no single specific size at which a lymph node is definitively considered cancerous. The likelihood of a lymph node being cancerous depends on a combination of factors, not just its size alone.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Freeman AM, Matto P. Lymphadenopathy. [Updated 2023 Feb 20]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513250/

- Maffei E, D’Ardia A, Ciliberti V, Serio B, Sabbatino F, Zeppa P, Caputo A. The Current and Future Impact of Lymph Node Fine-Needle Aspiration Cytology on Patient Care. Surg Pathol Clin. 2024 Sep;17(3):509-519. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2024.04.010. Epub 2024 May 23. PMID: 39129145.

- Jaiswal N, Bahadure S, Badge A, Dawande P, Mishra VH. Exploring the Spectrum of Lymphadenopathy: Insights From a Three-Year Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology Study in a Tertiary Care Center. Cureus. 2024 Apr 26;16(4):e59049. doi: 10.7759/cureus.59049. PMID: 38800335; PMCID: PMC11128070.

- Costagliola G, Consolini R. Lymphadenopathy at the crossroad between immunodeficiency and autoinflammation: An intriguing challenge. Clin Exp Immunol. 2021 Sep;205(3):288-305. doi: 10.1111/cei.13620. Epub 2021 Jun 20. PMID: 34008169; PMCID: PMC8374228.