TL;DR

Leukopenia is defined as a decrease in total white blood cells (leukocytes) below the normal range, increasing infection susceptibility. Normal Count: Typically 4,000-11,000 cells/µL; leukopenia is generally <4,000 cells/µL.

- Classification ▾: Mild (3,000-4,000), Moderate (1,500-3,000), Severe (<1,500) WBC/µL; Neutropenia severity (ANC) is also crucial.

- Causes ▾: Broadly categorized as bone marrow disorders (production), increased destruction, infections, medications, nutritional deficiencies, autoimmune disorders, and other factors.

- Symptoms ▾: Often subtle, primarily related to increased infection risk (frequent/severe infections, fever, sore throat, etc.) and sometimes underlying cause.

- Laboratory Investigations ▾: CBC with differential is key; peripheral blood smear and bone marrow exam help determine the cause. Specific tests target infections, autoimmune issues, etc.

- Treatment & Management ▾: Focuses on the underlying cause and supportive care to prevent/treat infections (hygiene, antimicrobials, G-CSF).

- Complications ▾: Primarily increased risk of infections (bacterial, viral, fungal, opportunistic), delayed wound healing, and sepsis. Severe leukopenia can be life-threatening.

*Click ▾ for more information

Introduction

Leukopenia simply means having a lower than normal number of white blood cells circulating in the blood. Since white blood cells are crucial for fighting off infections, leukopenia (low white cell count) can leave the body more vulnerable to various illnesses.

Function of White Blood Cells

White blood cells (WBCs), also known as leukocytes, are a diverse group of cells in the blood that are essential components of the immune system. Think of them as the body’s defense force, constantly patrolling the bloodstream and tissues.

Their primary function is to protect the body against infection and other diseases. They achieve this by:

- Identifying and destroying pathogens: This includes bacteria, viruses, fungi, parasites, and other foreign invaders. Different types of WBCs have specialized mechanisms for this, such as engulfing and digesting microbes (phagocytosis) or releasing toxic substances.

- Producing antibodies: Certain WBCs (lymphocytes called B cells) create antibodies, which are proteins that target specific pathogens, marking them for destruction by other immune cells.

- Regulating immune responses: WBCs help to coordinate and control the immune system’s activities, ensuring an effective and appropriate response to threats.

- Fighting abnormal cells: Some WBCs can recognize and destroy the body’s own cells that have become cancerous or infected with viruses.

- Participating in allergic reactions: Certain WBCs (basophils and eosinophils) are involved in allergic responses by releasing substances like histamine.

Types of Leukocytes

There are five main types of white blood cells (leukocytes), each with specialized roles in the immune system.

- Neutrophils: These are the most abundant type and act as the first responders to infection, primarily targeting bacteria and fungi through phagocytosis (engulfing and destroying them).

- Lymphocytes: These are crucial for adaptive immunity and come in three main subtypes:

- B cells: Produce antibodies that target specific pathogens.

- T cells: Directly attack infected or cancerous cells and help regulate the immune response.

- Natural Killer (NK) cells: Provide rapid responses against virus-infected cells and tumor cells.

- Monocytes: These are the largest type of WBC and differentiate into macrophages and dendritic cells in tissues. They perform phagocytosis and also present antigens to other immune cells.

- Eosinophils: These are involved in fighting parasitic infections and play a role in allergic reactions. They release toxic granules to kill parasites and modulate inflammatory responses.

- Basophils: These are the least common type and are involved in inflammatory responses and allergic reactions. They release histamine and other mediators that contribute to these processes.

What is Leukopenia (Low White Cell Count)?

White Blood Cell Count

The normal white blood cell (WBC) count in adults typically ranges from 4,000 to 11,000 cells per microliter (µL) of blood. This range can vary slightly between different laboratories due to variations in testing methods and populations studied. Some labs might also present the results in SI units as 4.0 to 11.0 x 10⁹/L.

Various factors can influence WBC counts in normal circumstances, including:

- Age: Newborns and young children typically have higher WBC counts than adults.

- Overall health: Infections, inflammation, stress, and certain medical conditions can cause temporary or sustained changes in WBC counts.

- Medications: Certain drugs can either increase or decrease WBC counts.

- Lifestyle factors: Smoking, diet, and physical activity levels can also have an impact.

- Time of day: WBC counts can fluctuate throughout the day.

- Ethnicity: Some ethnic groups may have naturally lower WBC counts.

The range for leukopenia (low white cell count) is generally considered to be a total white blood cell (WBC) count of less than 4,000 cells per microliter (µL) of blood (or < 4.0 x 10⁹/L).

Classification of Leukopenia

Leukopenia (low white cell count) is typically classified based on the severity of the reduction in the total white blood cell (WBC) count.

- Mild Leukopenia: Total WBC count between 3,000 and 4,000 cells per microliter (µL). Individuals with mild leukopenia (low white cell count) may have a slightly increased risk of infection, but often it is not clinically significant unless other risk factors are present or the decrease is persistent.

- Moderate Leukopenia: Total WBC count between 1,500 and 3,000 cells per microliter (µL). In this range, the risk of infection is more noticeable, and individuals may experience more frequent or prolonged infections.

- Severe Leukopenia: Total WBC count below 1,500 cells per microliter (µL). This level of leukopenia carries a significant risk of serious and even life-threatening infections, including opportunistic infections.

The Importance of Absolute Neutrophil Count (ANC)

While the total WBC count is a useful initial indicator, the absolute neutrophil count (ANC) is often a more critical factor in assessing the risk of infection in leukopenic patients. Neutrophils are the primary cells responsible for fighting bacterial and fungal infections.

In clinical practice, neutropenia is often the most concerning component of leukopenia (low white cell count) because a low neutrophil count directly correlates with an increased risk of bacterial and fungal infections.

Classification of Neutropenia Based on ANC

- Mild Neutropenia: ANC between 1,000 and 1,500 cells per microliter (µL). The risk of infection is usually minimal.

- Moderate Neutropenia: ANC between 500 and 1,000 cells per microliter (µL). The risk of infection is increased.

- Severe Neutropenia: ANC below 500 cells per microliter (µL). There is a high risk of serious bacterial and fungal infections.

Calculating ANC

The ANC is calculated by multiplying the total WBC count by the percentage of neutrophils (including both segmented neutrophils and bands) in the differential count.

ANC (cells/µL) = Total WBC count (cells/µL) × %Neutrophils (segmented + bands)/100

Clinical Significance of Classification

Understanding the degree of leukopenia and the severity of neutropenia helps clinicians to:

- Assess the patient’s risk of infection.

- Guide management strategies, such as the need for prophylactic antibiotics or growth factors.

- Monitor the patient’s condition over time.

- Investigate the underlying cause of the low blood counts.

So it is important to look beyond just the total WBC count when evaluating leukopenia (low white cell count). We need to pay close attention to the differential count, particularly the absolute neutrophil count, to accurately assess the patient’s risk and guide appropriate clinical decisions.

Causes of Leukopenia (Low White Cell Count)

Leukopenia (low white cell count) can arise from a variety of underlying conditions and factors. These causes can be broadly categorized into problems with production of white blood cells in the bone marrow, increased destruction or removal of white blood cells from circulation, and sequestration or pooling of white blood cells in certain organs.

Bone Marrow Disorders (Impaired Production)

The bone marrow is the primary site for the production of blood cells, including leukocytes. Damage or dysfunction here can lead to decreased production.

- Aplastic Anemia: A severe condition where the bone marrow fails to produce enough of all blood cell types (red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets). This can be idiopathic (unknown cause), autoimmune, or caused by infections, toxins, or radiation.

- Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS): A group of disorders where the bone marrow produces abnormal blood cells that don’t mature properly. This can lead to a deficiency in one or more blood cell types, including leukocytes.

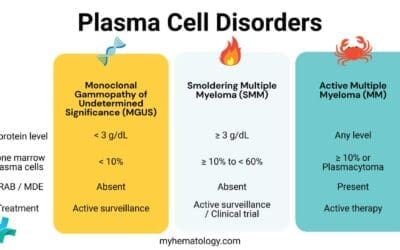

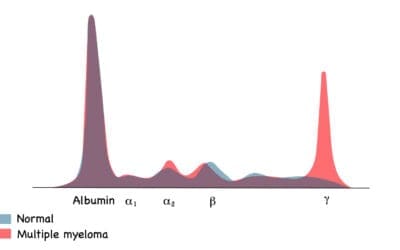

- Leukemia and Other Hematologic Malignancies: Infiltration of the bone marrow by cancerous cells (e.g., leukemia, lymphoma, multiple myeloma) can crowd out the normal production of healthy blood cells, leading to leukopenia (low white cell count).

- Myelofibrosis: A disorder where the bone marrow is replaced by fibrous scar tissue, impairing its ability to produce blood cells.

- Congenital Bone Marrow Failure Syndromes: Inherited conditions like Fanconi anemia, Diamond-Blackfan anemia, and severe congenital neutropenia can result in impaired white blood cell production from an early age.

- Nutritional Deficiencies: Deficiencies in essential nutrients like vitamin B12, folate, and copper are crucial for DNA synthesis and cell division in the bone marrow. Their lack can disrupt the production of all blood cells, including leukocytes.

Increased Destruction or Removal of White Blood Cells

Even if the bone marrow is producing enough white blood cells, their numbers in circulation can be reduced if they are being destroyed or removed prematurely.

- Hypersplenism: An enlarged spleen can trap and destroy blood cells, including leukocytes, leading to leukopenia (low white cell count). This can occur in conditions like liver disease, portal hypertension, and certain hematologic disorders.

- Autoimmune Neutropenia: The body’s immune system mistakenly produces antibodies that target and destroy neutrophils, leading to neutropenia, which often contributes to overall leukopenia (low white cell count).

- Drug-Induced Immune Destruction: Certain medications can trigger an immune response that leads to the destruction of white blood cells.

- Hemolysis: While primarily affecting red blood cells, severe and chronic hemolysis (destruction of red blood cells) can sometimes indirectly impact white blood cell survival or production.

Infections

Paradoxically, while white blood cells fight infections, certain infections can actually cause leukopenia (low white cell count).

- Viral Infections: Many viral infections, such as HIV, hepatitis viruses (especially hepatitis C), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), influenza, and parvovirus B19, can temporarily suppress bone marrow production of white blood cells or increase their destruction.

- Bacterial Infections: Some severe bacterial infections, like typhoid fever and brucellosis, can be associated with leukopenia (low white cell count). In overwhelming sepsis, there can be an initial leukocytosis (high WBC count) followed by leukopenia (low white cell count) as the bone marrow becomes exhausted or the WBCs are consumed at a rapid rate.

- Other Infections: Infections like malaria and miliary tuberculosis can also cause leukopenia (low white cell count).

Medications

Numerous medications can interfere with white blood cell production or increase their destruction.

- Chemotherapeutic Agents (Cytotoxic Drugs): These drugs are designed to kill rapidly dividing cells, including cancer cells, but they also affect the rapidly dividing cells in the bone marrow, leading to myelosuppression and leukopenia (low white cell count).

- Immunosuppressants: Drugs used to suppress the immune system (e.g., azathioprine, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil) can also inhibit bone marrow activity and reduce white blood cell counts.

- Certain Antibiotics: Some antibiotics, such as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, can occasionally cause leukopenia (low white cell count) as a side effect.

- Anticonvulsants: Certain anti-seizure medications can sometimes lead to a decrease in white blood cell counts.

- Psychotropic Medications: Some antipsychotics and antidepressants have been associated with leukopenia (low white cell count) in rare cases.

- Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): Leukopenia (low white cell count) is a rare side effect of some NSAIDs.

Autoimmune Disorders

In autoimmune diseases, the immune system mistakenly attacks the body’s own tissues, which can sometimes include bone marrow cells or circulating white blood cells.

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE): Can cause leukopenia (low white cell count) through various mechanisms, including autoimmune destruction.

- Rheumatoid Arthritis (Felty’s Syndrome): Characterized by rheumatoid arthritis, splenomegaly, and neutropenia (often leading to leukopenia).

Other Causes

- Sepsis: As mentioned earlier, while often starting with leukocytosis, severe sepsis can lead to leukopenia (low white cell count) due to bone marrow exhaustion, increased consumption, and demargination of WBCs.

- Major Surgery or Trauma: Can sometimes temporarily suppress bone marrow function.

- Radiation Therapy: Radiation, especially when directed at large areas of the bone marrow, can damage hematopoietic stem cells and lead to leukopenia (low white cell count).

- Hemodialysis: Some individuals undergoing hemodialysis may experience leukopenia (low white cell count).

Symptoms of Leukopenia

The signs and symptoms of leukopenia are often subtle and may not be directly attributable to the low white blood cell count itself. Instead, they primarily arise from the increased susceptibility to infections that results from a weakened immune system. Additionally, some symptoms might be related to the underlying cause of the leukopenia (low white cell count).

Symptoms Related to Increased Susceptibility to Infections

Because white blood cells are the body’s primary defense against pathogens, a reduced number makes it harder to fight off infections.

- Frequent Infections: Individuals with leukopenia (low white cell count) may experience infections more often than usual. These can be common infections that most people can easily fight off.

- Recurrent Infections: Infections may keep coming back, even after treatment.

- Prolonged Infections: Infections may last longer and be more difficult to resolve.

- More Severe Infections: Even common infections can become more serious and lead to complications.

- Unusual or Opportunistic Infections: In cases of severe leukopenia (low white cell count), individuals may develop infections caused by organisms that typically don’t cause illness in people with healthy immune systems (opportunistic infections).

Specific signs and symptoms of these infections can vary depending on the site and type of infection, but may include:

- Fever: Often a key sign of infection.

- Chills: May accompany fever.

- Sore Throat: Suggestive of pharyngitis or tonsillitis.

- Mouth Ulcers or Sores: Can be a sign of oral infections or mucositis (inflammation of the mucous membranes).

- Swollen Lymph Nodes (Lymphadenopathy): Indicates the immune system is active, often in response to infection, but may be less pronounced in severe leukopenia.

- Skin Infections: Redness, swelling, pain, warmth, and pus at the site of infection (e.g., cellulitis, boils).

- Cough and Shortness of Breath: May indicate a respiratory infection like bronchitis or pneumonia.

- Diarrhea: Can be a sign of gastrointestinal infection.

- Pain or Burning During Urination (Dysuria): Suggests a urinary tract infection.

- Fatigue and Weakness: Can be general symptoms of illness and infection.

Direct Symptoms of Low White Cell Count (Often Subtle)

Sometimes, individuals with leukopenia (low white cell count) may experience more general symptoms that could be related to the reduced number of immune cells, although these are often less specific.

- Fatigue: Feeling unusually tired or lacking energy.

- Weakness: A general feeling of being physically weak.

Symptoms Related to the Underlying Cause of Leukopenia

In some cases, the symptoms of leukopenia (low white cell count) might be overshadowed by or occur alongside symptoms of the underlying condition causing the low white cell count.

- Bone Pain or Tenderness: May occur in leukemia or other bone marrow disorders.

- Easy Bruising or Bleeding: Can be present if the bone marrow disorder also affects platelet production.

- Swollen Spleen (Splenomegaly) or Liver (Hepatomegaly): May be seen in hypersplenism, leukemia, or lymphoma.

- Weight Loss: Can occur in malignancies or chronic infections like HIV.

- Skin Rashes or Joint Pain: May be associated with autoimmune disorders like lupus.

- Pale Skin (Pallor): Can indicate anemia, which may coexist with leukopenia (low white cell count) in bone marrow disorders.

- Night Sweats: May occur in lymphomas or certain infections.

- Lymph Node Enlargement (Generalized Lymphadenopathy): Can be seen in lymphomas, leukemia, or certain infections.

Laboratory Investigations

When leukopenia (low white cell count) is suspected or identified through a routine complete blood count (CBC), a series of laboratory investigations are crucial to confirm the finding, assess its severity, and, most importantly, determine the underlying cause.

Confirming and Characterizing Leukopenia (low white cell count)

Complete Blood Count (CBC) with Differential

This is the cornerstone of the initial evaluation.

- Total White Blood Cell (WBC) Count: Confirms the presence and severity of leukopenia.

- White Blood Cell Differential: Provides the absolute counts and percentages of each type of leukocyte (neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, and basophils). This is critical for identifying specific deficiencies, such as neutropenia (low neutrophils), which is often the most clinically significant component of leukopenia.

- Red Blood Cell (RBC) Count, Hemoglobin, Hematocrit: Helps to identify any associated anemia, which can occur in bone marrow disorders.

- Platelet Count: Assesses for thrombocytopenia (low platelets), which may also be present in bone marrow failure or infiltrative processes.

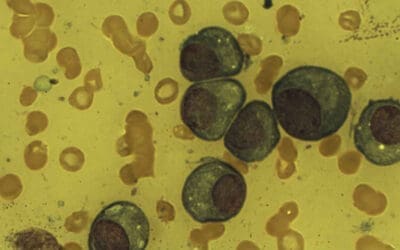

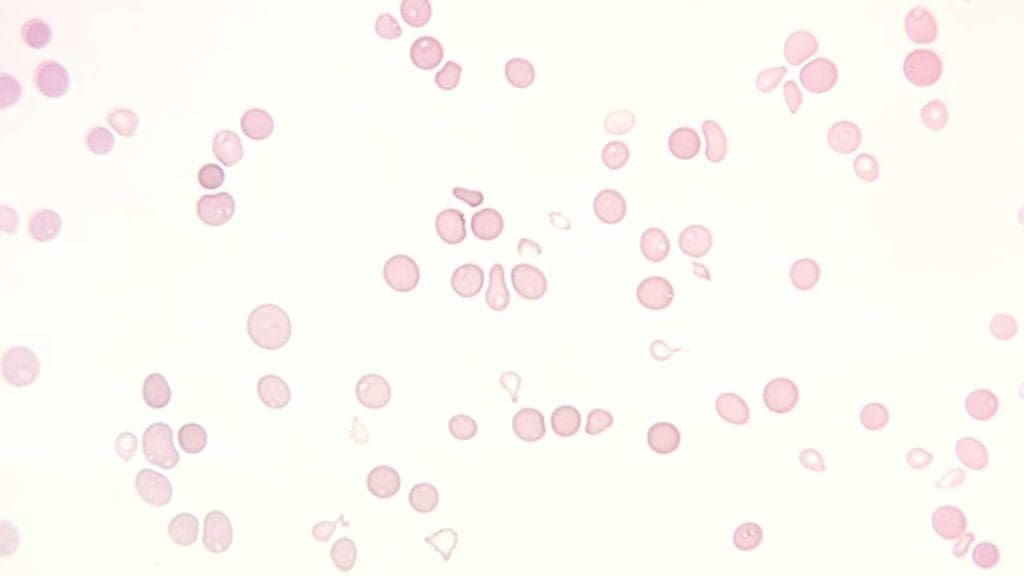

Peripheral Blood Smear

Morphology of the blood cells will be examined by a trained professional to be compared to the quantitative complete blood count results. Peripheral blood smear examination allows for identification of qualitative abnormalities that could not be interpreted through the complete blood count.

- Morphology of White Blood Cells: Abnormalities in the appearance of WBCs can suggest certain conditions like myelodysplastic syndromes, leukemia (blasts), or viral infections (atypical lymphocytes).

- Presence of Immature Cells: Detection of immature WBCs in the peripheral blood can indicate a bone marrow disorder.

- Red Blood Cell Morphology: Helps identify any coexisting red cell abnormalities.

- Platelet Morphology and Count Estimation: Provides a visual assessment of platelet size and number.

Investigating the Underlying Cause

Based on the initial findings from the CBC and peripheral blood smear, further investigations are directed at identifying the etiology of the leukopenia (low white cell count).

Bone Marrow Aspiration and Biopsy

This is often the definitive diagnostic procedure for many causes of leukopenia (low white cell count), especially when bone marrow disorders are suspected (e.g., unexplained persistent leukopenia, abnormal peripheral blood smear, pancytopenia).

- Aspiration: A liquid sample of the bone marrow is obtained and examined under a microscope to assess cellularity, maturation of blood cells, and the presence of abnormal cells.

- Biopsy: A core sample of bone marrow tissue is taken to evaluate the overall architecture of the bone marrow and assess for infiltration by abnormal cells or fibrosis.

- Special Stains and Flow Cytometry: These techniques can be performed on bone marrow samples to further characterize abnormal cells and identify specific markers associated with hematologic malignancies or other conditions.

- Cytogenetic and Molecular Studies: Chromosomal abnormalities and genetic mutations in bone marrow cells can be identified to diagnose conditions like MDS, leukemia, and certain congenital disorders.

Infectious Disease Workup

If infection is suspected as the cause of leukopenia (low white cell count).

- Blood Cultures: To identify bacterial or fungal infections in the bloodstream.

- Viral Serology: Tests for antibodies or antigens of specific viruses known to cause leukopenia (e.g., HIV, EBV, CMV, hepatitis viruses, parvovirus B19).

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Assays: To detect viral or bacterial DNA/RNA in blood or other body fluids.

- Other Specific Tests: Depending on the clinical suspicion (e.g., tests for tuberculosis, malaria).

Autoimmune Workup

If an autoimmune disorder is suspected.

- Antinuclear Antibodies (ANA): A screening test for various autoimmune diseases, including SLE.

- Rheumatoid Factor (RF): Associated with rheumatoid arthritis.

- Anti-dsDNA Antibodies: Specific for SLE.

- Anti-Sm Antibodies: Also specific for SLE.

- Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibodies (ANCA): Associated with certain vasculitides.

- Direct Antiglobulin Test (DAT) or Coombs Test: May be relevant if autoimmune destruction of blood cells is suspected.

Nutritional Studies

If nutritional deficiencies are a possible cause.

- Vitamin B12 and Folate Levels: To assess for deficiencies.

- Serum Copper Levels: To check for copper deficiency.

- Iron Studies (Serum Iron, Ferritin, Transferrin): To evaluate for iron deficiency, which can sometimes be associated with other hematologic abnormalities.

Drug History and Review

A meticulous review of the patient’s medication list, including prescription, over-the-counter drugs, and supplements, is essential to identify potential drug-induced leukopenia (low white cell count). Discontinuation of the suspected drug may be necessary to observe for recovery of the WBC count.

Imaging Studies

These may be indicated in certain situations.

- Spleen Size Assessment (Ultrasound, CT Scan): To evaluate for splenomegaly, which can contribute to leukopenia (low white cell count) through sequestration and destruction of blood cells.

- Lymph Node Biopsy: If lymphadenopathy is present and lymphoma or certain infections are suspected.

- Chest X-ray or CT Scan: To evaluate for infections or other abnormalities in the chest.

Genetic Testing

In cases of suspected congenital bone marrow failure syndromes or inherited forms of neutropenia, genetic testing may be performed to identify specific mutations.

The specific laboratory investigations ordered will depend on the individual patient’s clinical presentation, medical history, and initial findings. A systematic and logical approach is necessary to efficiently and accurately diagnose the underlying cause of leukopenia and guide appropriate management.

Treatment and Management of Leukopenia

The treatment and management of leukopenia are primarily focused on addressing the underlying cause of the low white blood cell count and preventing or treating any resulting infections. The approach varies significantly depending on the etiology and severity of the leukopenia.

Addressing the Underlying Cause

Identifying and treating the root cause is the most crucial aspect of managing leukopenia.

- Treating Infections: If leukopenia is secondary to an infection (viral, bacterial, fungal, or parasitic), the primary focus is on eradicating the infection with appropriate antimicrobial agents (antibiotics, antivirals, antifungals, antiparasitics). Once the infection resolves, the white blood cell count often returns to normal.

- Discontinuing Offending Medications: If a medication is suspected of causing leukopenia (low white cell count) , the first step is usually to discontinue the drug, if clinically feasible. The white blood cell count should be monitored to see if it recovers. Sometimes, an alternative medication may be necessary.

- Managing Autoimmune Disorders: For leukopenia (low white cell count) associated with autoimmune diseases (e.g., SLE, rheumatoid arthritis), treatment involves managing the underlying autoimmune condition with immunosuppressants, corticosteroids, or other immunomodulatory therapies. The goal is to reduce the autoimmune attack on white blood cells or the bone marrow.

- Supplementing Nutritional Deficiencies: If vitamin B12, folate, or copper deficiency is identified as the cause, supplementation with the deficient nutrient is essential. This can often lead to a recovery of the white blood cell count.

- Treating Hematologic Malignancies and Bone Marrow Disorders: Management of leukopenia due to conditions like leukemia, lymphoma, MDS, aplastic anemia, or myelofibrosis is complex and depends on the specific diagnosis and stage of the disease. Treatment modalities can include:

- Chemotherapy: To destroy cancerous cells in leukemia and lymphoma.

- Radiation Therapy: To target cancerous cells.

- Stem Cell Transplantation (Bone Marrow Transplant): May be an option for severe aplastic anemia, leukemia, MDS, and other bone marrow failure syndromes to replace damaged or diseased bone marrow with healthy stem cells.

- Immunomodulatory Drugs: Used in some cases of MDS and multiple myeloma.

- Supportive Care: Including blood transfusions and growth factors.

- Managing Hypersplenism: If an enlarged spleen is causing significant leukopenia (and potentially other cytopenias), treatment options might include addressing the underlying cause of splenomegaly or, in some cases, splenectomy (surgical removal of the spleen).

Supportive Care

While addressing the underlying cause, supportive measures are crucial to prevent and manage complications related to the low white blood cell count, particularly the increased risk of infection.

- Preventing Infections

- Strict Hand Hygiene: Frequent and thorough handwashing by the patient and caregivers is paramount.

- Avoiding Crowds and Sick Individuals: Minimizing exposure to potential sources of infection.

- Vaccinations: Maintaining up-to-date vaccinations (when appropriate and as advised by the healthcare provider). Live vaccines are generally contraindicated in individuals with significant immunosuppression.

- Safe Food Handling: Practicing food safety to reduce the risk of foodborne illnesses.

- Good Personal Hygiene: Maintaining oral and skin hygiene to prevent infections.

- Managing Infections

- Prompt Evaluation of Fever: Any fever in a leukopenic patient is considered a medical emergency and requires immediate evaluation to identify the source of infection and initiate appropriate antimicrobial therapy.

- Broad-Spectrum Antibiotics: Often started empirically (before the specific pathogen is identified) in febrile neutropenic patients due to the high risk of rapid deterioration.

- Targeted Antimicrobial Therapy: Once the causative organism is identified, treatment is tailored to the specific pathogen.

- Antiviral and Antifungal Medications: Used as indicated for viral or fungal infections.

- Growth Factors (Colony-Stimulating Factors – G-CSFs): These are synthetic substances that stimulate the bone marrow to produce more white blood cells, particularly neutrophils. The use of G-CSFs is carefully considered based on the underlying condition and potential benefits and risks.

- Filgrastim (Neupogen), Pegfilgrastim (Neulasta), Sargramostim (Leukine): These are examples of G-CSFs that may be used in specific situations, such as:

- Severe neutropenia.

- Febrile neutropenia (along with antibiotics).

- After certain types of chemotherapy to reduce the duration and severity of neutropenia.

- In some cases of congenital neutropenia or aplastic anemia.

- Filgrastim (Neupogen), Pegfilgrastim (Neulasta), Sargramostim (Leukine): These are examples of G-CSFs that may be used in specific situations, such as:

- Blood Transfusions: While not a direct treatment for leukopenia, blood transfusions (specifically white blood cell transfusions) are rarely used due to the short lifespan and potential for adverse reactions of transfused WBCs. They might be considered in very specific and severe situations where other measures have failed and there is a life-threatening infection. Red blood cell and platelet transfusions may be necessary if the underlying condition also causes anemia or thrombocytopenia.

- Protective Isolation (Reverse Isolation): In cases of severe and prolonged neutropenia, especially in hospital settings, measures to protect the patient from external sources of infection may be implemented. This can include wearing masks, gowns, and gloves by healthcare providers and visitors, and placing the patient in a private room with filtered air.

Monitoring and Follow-up

Regular monitoring of white blood cell counts (usually with serial CBCs) is essential to assess the response to treatment, track the trend of leukopenia, and detect any complications early. The frequency of monitoring depends on the severity of the leukopenia and the underlying condition. Close clinical follow-up is also necessary to assess for signs and symptoms of infection or progression of the underlying disease.

Potential Complications of Leukopenia

Leukopenia (low white cell count) significantly impairs the body’s ability to fight off infections, making individuals more susceptible to a range of complications. The severity and type of complications often depend on the degree and duration of the leukopenia, as well as the specific type of white blood cell that is most affected (e.g., neutrophils in neutropenia).

Increased Risk of Infections

This is the most direct and significant complication of leukopenia (low white cell count) . The lower the white blood cell count, the higher the risk and severity of infections.

- Bacterial Infections: Individuals with neutropenia are particularly vulnerable to bacterial infections, which can range from common skin infections and urinary tract infections to serious bloodstream infections (sepsis) and pneumonia. These infections can progress rapidly and become life-threatening.

- Viral Infections: Leukopenia can also increase susceptibility to viral infections, including reactivation of latent viruses (like herpes simplex or shingles) or more severe presentations of common viral illnesses (like influenza or respiratory syncytial virus).

- Fungal Infections: In cases of severe and prolonged leukopenia (low white cell count) , especially neutropenia, the risk of invasive fungal infections (e.g., aspergillosis, candidiasis) is significantly elevated. These infections can be challenging to treat and have high mortality rates.

- Parasitic Infections: While less common in developed countries, leukopenia (low white cell count) can increase susceptibility to certain parasitic infections, particularly in immunocompromised individuals.

- Opportunistic Infections: When the immune system is severely weakened by profound leukopenia, individuals can develop infections caused by organisms that typically do not cause disease in healthy people (e.g., Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, infections with certain molds or atypical bacteria).

Delayed Wound Healing

White blood cells, particularly neutrophils and macrophages (derived from monocytes), play a crucial role in the inflammatory response and tissue repair. In leukopenic individuals, the reduced number of these cells can impair the body’s ability to effectively clear debris, fight off infection at the wound site, and promote the healing process. This can lead to:

- Slower healing of cuts, scrapes, and surgical wounds.

- Increased risk of wound infections.

- Poor wound closure.

Sepsis and Septic Shock

Sepsis is a life-threatening condition that arises when the body’s response to an infection damages its own tissues and organs. Leukopenic individuals are at a higher risk of developing severe infections that can progress to sepsis and septic shock, characterized by:

- High fever (or sometimes low temperature in severe cases).

- Rapid heart rate.

- Rapid breathing.

- Confusion or altered mental status.

- Low blood pressure that doesn’t respond to fluids (septic shock).

- Organ dysfunction.

Sepsis is a medical emergency requiring immediate and aggressive treatment, including antibiotics, fluid resuscitation, and organ support.

Mucositis

Mucositis is the inflammation and ulceration of the mucous membranes lining the digestive tract, from the mouth to the anus. It is a common side effect of chemotherapy and radiation therapy, which can cause leukopenia. However, even in the context of other causes of leukopenia, the reduced number of immune cells can make individuals more susceptible to infections and inflammation of the mucous membranes, leading to:

- Painful mouth sores.

- Difficulty eating and swallowing.

- Increased risk of local and systemic infections.

- Diarrhea.

Increased Risk of Certain Cancers

In some cases, the underlying cause of leukopenia (low white cell count) can also increase the risk of developing certain cancers, particularly hematologic malignancies like leukemia or lymphoma. For example, individuals with myelodysplastic syndromes (a cause of leukopenia) have an increased risk of progressing to acute myeloid leukemia. Similarly, chronic infections like HIV (another cause of leukopenia) can increase the risk of certain cancers.

Complications Related to the Underlying Cause

It’s important to remember that leukopenia is often a symptom of an underlying condition, and individuals may also experience complications related to that primary disease. For instance, someone with severe aplastic anemia (causing leukopenia) may also suffer from complications related to low red blood cell counts (anemia) and low platelet counts (thrombocytopenia), such as fatigue, weakness, and bleeding.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Is leukopenia life threatening?

Yes, leukopenia can be life-threatening, primarily due to the significantly increased risk of severe infections. While a low white blood cell count itself isn’t painful or immediately dangerous, it weakens the body’s immune system, making it difficult to fight off pathogens.

Can stress cause low WBC?

While acute stress can sometimes cause a temporary increase in white blood cell count as part of the body’s “fight or flight” response, chronic or severe stress can potentially lead to a decrease in white blood cell count (leukopenia) in some individuals.

Can lack of sleep cause low white blood cell count?

Yes, chronic lack of sleep can potentially contribute to a lower white blood cell count (leukopenia) in some individuals.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Shoenfeld Y, Alkan ML, Asaly A, Carmeli Y, Katz M. Benign familial leukopenia and neutropenia in different ethnic groups. Eur J Haematol. 1988 Sep;41(3):273-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1988.tb01192.x. PMID: 3181399.

- Ing VW. The etiology and management of leukopenia. Can Fam Physician. 1984 Sep;30:1835-9. PMID: 21279100; PMCID: PMC2154209.

- Pettersson H, Alani T, Rydén I, Stödberg T, Eksborg S, Sundin M. Leukopenia in Children on Anti-Seizure Medication Is Common with Minor Clinical Impact. J Pediatr. 2025 Apr 17:114593. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2025.114593. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40252960.

- Choi TY, Lee MS, Ernst E. Moxibustion for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced leukopenia: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Support Care Cancer. 2015 Jun;23(6):1819-26. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2530-7. Epub 2014 Dec 5. PMID: 25471180.

- Giamarellou H, Antoniadou A. Infectious complications of febrile leukopenia. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2001 Jun;15(2):457-82. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70156-2. PMID: 11447706.

- Adamietz IA, Rosskopf B, Dapper FD, von Lieven H, Boettcher HD. Comparison of two strategies for the treatment of radiogenic leukopenia using granulocyte colony stimulating factor. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996 Apr 1;35(1):61-7. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(96)85012-7. PMID: 8641928.