TL;DR

Acute myeloid leukemia or AML for short is an aggressive, fast-growing cancer where the bone marrow produces “blasts” (immature myeloid cells) that can’t mature into functional blood cells.

- Predisposing factors ▾: DNA damaging agents e.g. radiotherapy, chemotherapy, Iinherited DNA repair mutations, smoking, toxins e.g. benzene & MPN/MDS

- Pathogenesis ▾: A “multi-hit” genetic process. Often starts with a quiet mutation (CHIP) followed by a “trigger” mutation (like FLT3 or NPM1) that causes the cells to proliferate wildly.

- Signs and symptoms ▾: Triad of bone marrow failure; Anemia (Fatigue and pallor), Neutropenia (Recurrent, severe infections/fevers), & Thrombocytopenia (Petechiae, bruising, and gum bleeding).

- Laboratory Investigations ▾:

- Flow Cytometry: To find myeloid markers (CD33, CD13, MPO).

- Cytogenetics: To find chromosomal translocations.

- Molecular/NGS: To find specific mutations in DNA (FLT3, NPM1, IDH1/2).

- Treatment and Management ▾:

- Induction: The “7+3” regimen (7 days of Cytarabine, 3 days of Anthracycline) to clear the marrow.

- Consolidation: Extra chemo or a Stem Cell Transplant to keep the leukemia from coming back.

- Emergency Complications ▾: Neutropenic Sepsis (overwhelming infection) and Leukostasis (blood becoming too “thick” with blasts, causing strokes or lung issues).

*Click ▾ for more information

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia or AML encompasses a group of molecularly distinct entities that share a single morphologic feature, the accumulation of undifferentiated blasts of myeloid origin in the bone marrow.

It is an aggressive neoplasm caused by acquired somatic defects due to either environmental influences e.g. chemicals, drugs, radiation or infections in early hematopoietic blast cells that block differentiation leading to accumulation of undifferentiated blasts in the marrow, spilling into the peripheral blood and infiltrate other tissues.

Leukemia blasts are too immature to be functional and are prone to suppress or supplant the production of normal hematopoiesis causing pancytopenia.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a sophisticated, multi-step process defined by genetic mutations and epigenetic alterations that disrupt the normal “blueprint” of blood cell production. Rather than a single accident, it is typically an accumulation of errors that lead to two primary outcomes: uncontrolled growth and frozen development.

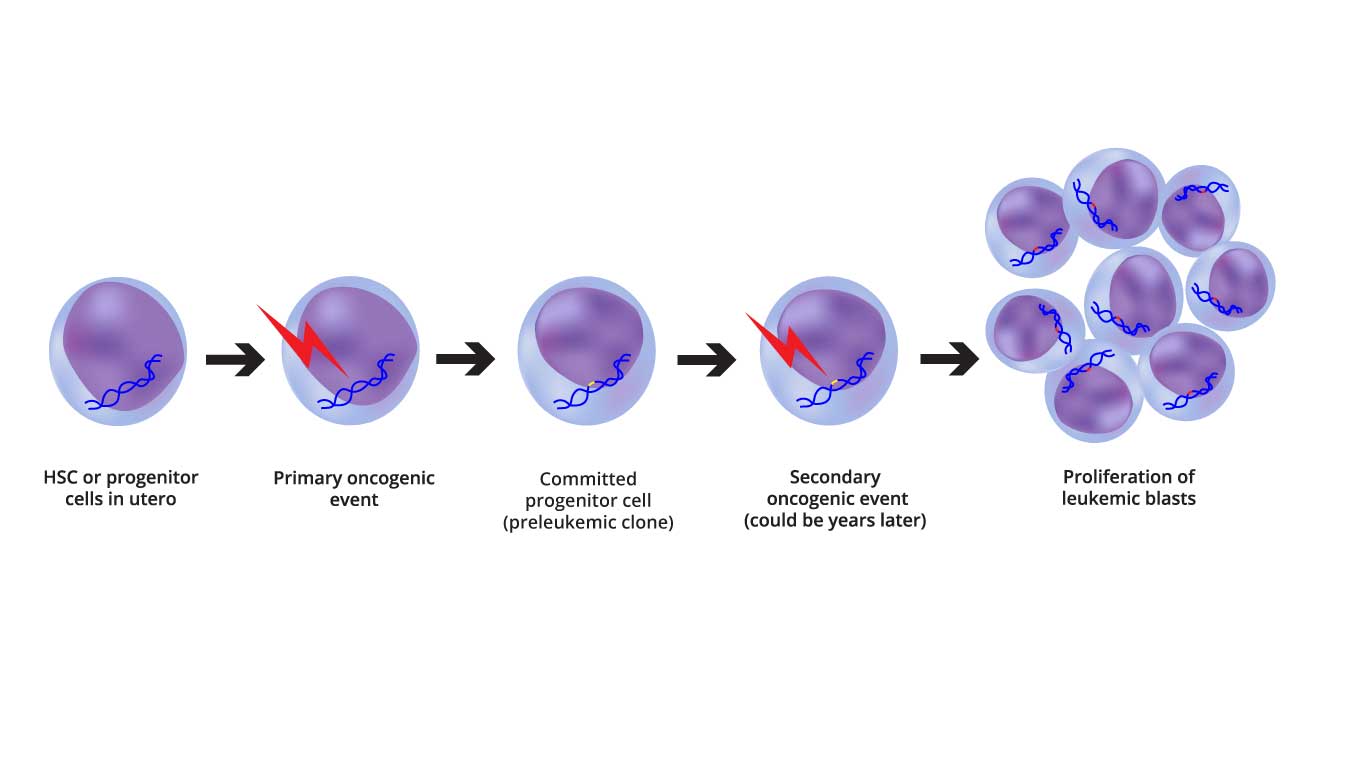

The “Multi-Hit” Hypothesis

Image depicting the two-step oncogenic model of AML pathogenesis, highlighting the initial genetic alterations and the subsequent epigenetic and transcriptional changes.

In hematology, we traditionally view AML through the lens of the “Two-Hit Model,” though modern genomics shows it is often even more complex.

- Class I Mutations (The “Gas Pedal”): These mutations provide a proliferative advantage. They activate signal transduction pathways that tell the cell to divide constantly. Examples: FLT3-ITD, KIT, and RAS mutations.

- Class II Mutations (The “Brakes”): These mutations affect transcription factors and disrupt cell differentiation. They are responsible for the “differentiation arrest,” where cells are stuck as immature blasts. Examples: NPM1 mutations or translocations like t(8;21) or inv(16).

- Epigenetic Mutations (The “Architect”): These are often the “founding” mutations. They don’t change the DNA sequence but change how DNA is “packaged,” affecting which genes are turned on or off. Examples: DNMT3A, TET2, and IDH1/2.

From CHIP to AML: The Timeline

One of the most fascinating aspects of AML pathogenesis is that it often begins years before symptoms appear.

- Clonal Hematopoiesis of Indeterminate Potential (CHIP): As we age, a single hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) may acquire a mutation (often in DNMT3A). This cell creates a “clone”—a family of cells that look and act normal but carry this “first hit.”

- Pre-Leukemic Evolution: Over time, these clones may acquire more mutations. They are more resilient than healthy cells and slowly begin to dominate the bone marrow “real estate.”

- The Transformation: A final, aggressive mutation (like a FLT3 mutation) occurs. This is the “tipping point” that transforms the pre-leukemic clone into full-blown acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

Differentiation Arrest and Marrow Failure

Once the leukemic clone is established, the bone marrow environment changes drastically. The leukemic blasts proliferate so rapidly that they physically crowd out healthy stem cells. The leukemia cells “reprogram” the bone marrow niche (the “soil”) to support their own survival while making it hostile for healthy red cells, white cells, and platelets. Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells develop ways to ignore “cell suicide” signals (apoptosis), allowing them to survive even when they are damaged or under stress.

Associated Risk Factors

While having one or more risk factors does not mean a person will definitely develop acute myeloid leukemia (AML), these elements contribute to the cumulative DNA damage required for the disease to manifest.

Environmental and Lifestyle Factors

These are factors often related to exposure over time, which explains why acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is primarily a disease of older adults.

- Smoking: Tobacco smoke is one of the few preventable causes of acute myeloid leukemia (AML). It contains benzene, a known human carcinogen. Studies suggest current smokers have a 40% increased risk compared to non-smokers.

- Benzene Exposure: Beyond smoking, benzene is used in industrial processes (petroleum refining, chemical manufacturing, rubber production). Occupations such as chemical plant workers, refinery workers, and even painters or printers may face higher risks if exposure is prolonged.

- Ionizing Radiation: Survivors of atomic incidents or people exposed to high doses of radiation (including those receiving radiation therapy for other cancers) have an increased risk. However, the risk from standard diagnostic X-rays or CT scans is considered very low.

Medical History and Prior Treatments

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) that develops as a result of previous medical treatments is often referred to as Secondary or Therapy-related AML (t-AML).

- Previous Chemotherapy: Certain drugs used to treat other cancers (like breast cancer or Hodgkin lymphoma) can damage the DNA of bone marrow cells. Key culprits include:

- Alkylating Agents: (e.g., cyclophosphamide, melphalan) typically cause AML 5–7 years after treatment.

- Topoisomerase II Inhibitors: (e.g., etoposide) can lead to AML more quickly, often within 1–3 years.

- Pre-existing Blood Disorders: Conditions that affect how the bone marrow produces cells can “transform” into AML. These include:

- Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS): Often called “pre-leukemia.”

- Myeloproliferative Neoplasms (MPNs): Such as polycythemia vera or essential thrombocythemia.

- Aplastic Anemia.

Genetic and Congenital Factors

While AML is rarely inherited (most cases are “sporadic”), certain genetic conditions predispose individuals to the disease.

- Inherited Syndromes: Conditions that impair DNA repair or bone marrow function increase risk:

- Fanconi Anemia: A rare disorder that prevents marrow from making enough new blood cells.

- Bloom Syndrome and Li-Fraumeni Syndrome.

- Down Syndrome: Children with Down syndrome have a 10 to 30 times higher risk of developing leukemia.

- Demographics:

- Age: The most significant non-modifiable risk factor; the median age at diagnosis is approximately 68 years.

- Gender: AML is slightly more common in males than females, potentially due to differences in occupational exposures or genetic protective factors in females.

Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) Symptoms

The clinical presentation of Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) is a direct reflection of its pathophysiology: the bone marrow becomes so densely packed with non-functional “blasts” that it can no longer produce healthy blood cells. This results in a rapid onset of symptoms, usually over just a few days or weeks.

Consequences of Bone Marrow Failure

The most common symptoms are grouped by the specific cell line that is being suppressed.

- Anemia (Low Red Blood Cells):

- Fatigue and Malaise: Often the first sign; a profound, “bone-deep” exhaustion.

- Pallor: Visible paleness in the skin, conjunctiva, and nail beds.

- Dyspnea: Shortness of breath, especially during exertion.

- Neutropenia (Low Functional White Blood Cells):

- Recurrent Infections: Patients may struggle to shake off a cold or develop severe pneumonia.

- Fever and Chills: Often the only sign of a life-threatening infection (neutropenic fever).

- Mouth Ulcers: Painful sores in the oral mucosa.

- Thrombocytopenia (Low Platelets):

- Bleeding Gums and Epistaxis: Bleeding from the nose or mouth.

- Petechiae and Purpura: Small, pinpoint red/purple spots on the skin that do not blanch when pressed.

- Ecchymosis: Large, unexplained bruises.

Extramedullary Infiltration (Blasts spreading outside the marrow)

In some subtypes of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), the leukemic cells migrate to other tissues, leading to specific physical findings.

- Gingival Hyperplasia: This is classic for monocytic subtypes (like the old FAB M4 and M5). The gums become swollen, painful, and literally “grow” over the teeth.

- Leukemia Cutis: The presence of firm, painless, skin-colored to purple nodules or plaques.

- Organomegaly: While more common in chronic leukemias, AML can cause a moderately enlarged liver (hepatomegaly) or spleen (splenomegaly).

- Bone Pain: Caused by the high pressure of rapidly expanding blast populations inside the marrow cavity, often felt in the long bones or sternum.

Hypermetabolic and Metabolic Symptoms

Because the cancer cells are dividing so rapidly, they consume vast amounts of the body’s energy:

- B-Symptoms: Unintentional weight loss, drenching night sweats, and persistent low-grade fever.

- Tumor Lysis Syndrome (TLS): If the white cell count is extremely high, cells may “burst” spontaneously, releasing potassium and uric acid into the blood, which can lead to kidney failure or arrhythmias even before treatment starts.

Hematologic Emergencies

In severe cases, acute myeloid leukemia (AML) presents with life-threatening complications that require immediate intervention:

Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC): Particularly common in Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia (APL). Patients may present with catastrophic bleeding and simultaneous clotting because the leukemic cells release pro-coagulant factors.

Leukostasis: When the white blood cell count is very high (>100,000/µL), the blood becomes viscous or “sludge-like.” This can cause respiratory distress (lung clogs) or neurological changes like confusion or stroke-like symptoms (brain clogs).

Neutropenic Sepsis: Neutropenic sepsis is the #1 cause of treatment-related mortality in acute myeloid leukemia (AML). It is a life-threatening medical emergency where a patient with a dangerously low white blood cell count (neutrophils) develops a systemic inflammatory response to an infection. Because these patients lack the cells to create a localized inflammatory response, fever is often the only warning sign. If an acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patient feels ‘unwell’ or has a temperature, the ‘Golden Hour’ protocol must be triggered immediately, regardless of how stable they look.” For acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients, this is not just “an infection”, it is a race against time because they lack the “infantry” (neutrophils) needed to keep bacteria from invading the bloodstream and organs.

Modern Laboratory Diagnosis: From Morphology to Molecular Profiling

The laboratory diagnosis of Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) has evolved from simply looking at cells under a microscope to a complex integration of morphology, protein expression, and genetic “fingerprinting.”

Peripheral Blood (The Initial Screen)

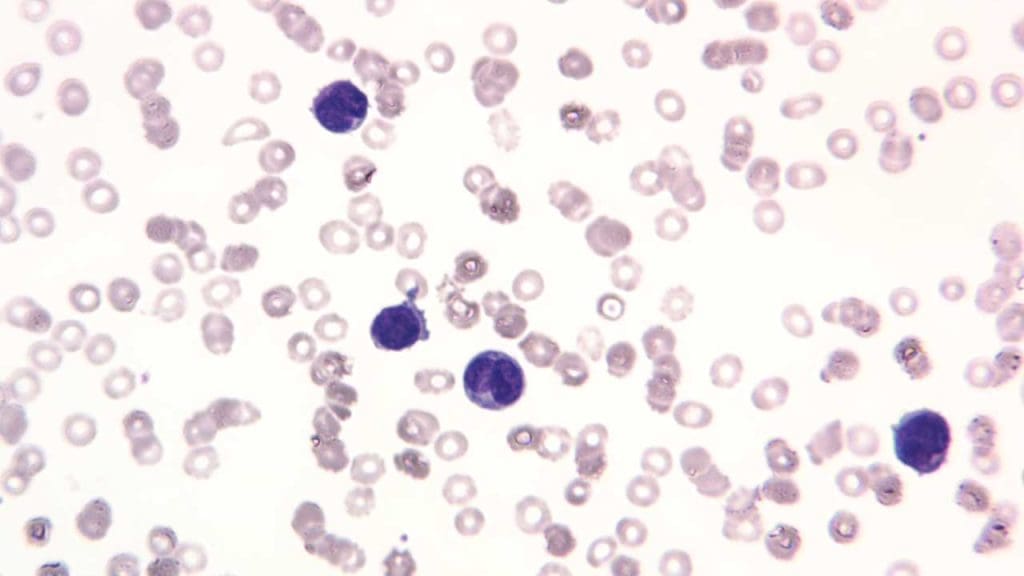

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): Usually reveals pancytopenia (low hemoglobin, low platelets, and low mature neutrophils). The White Blood Cell (WBC) count is highly variable. It can be low, normal, or extremely high (over 100,000/µL).

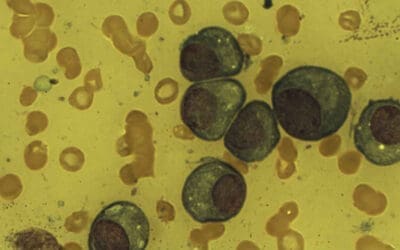

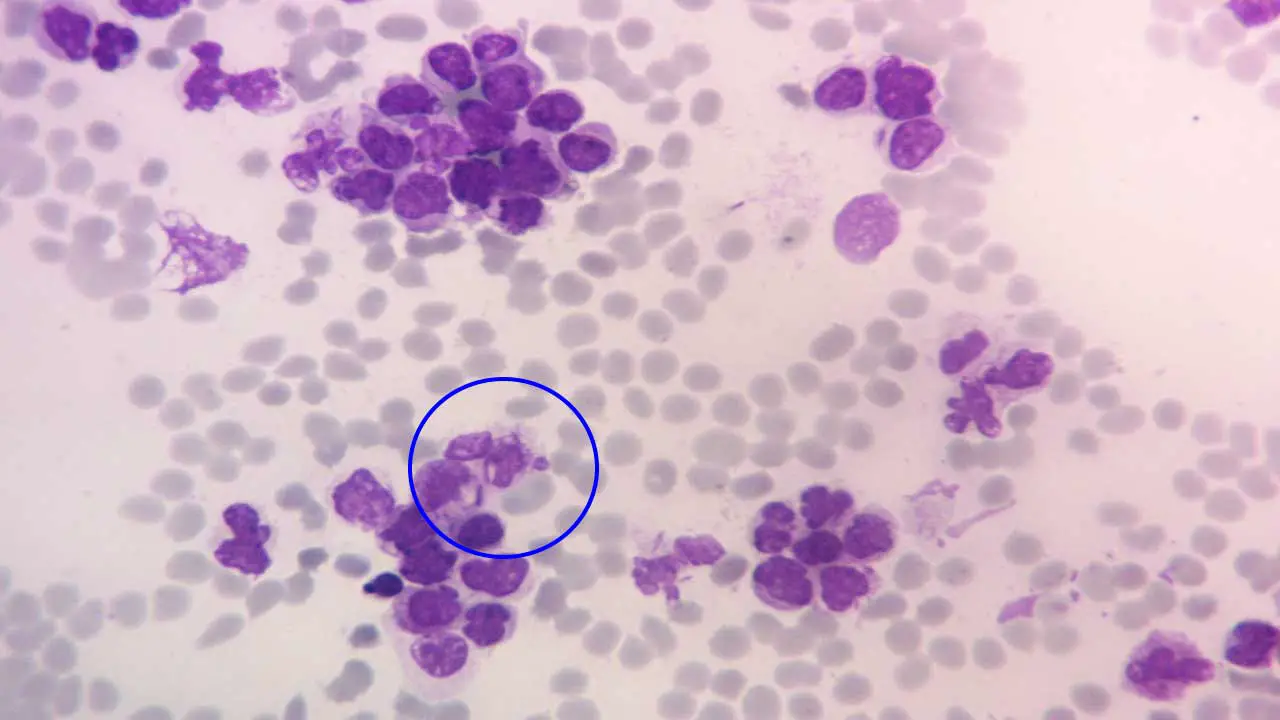

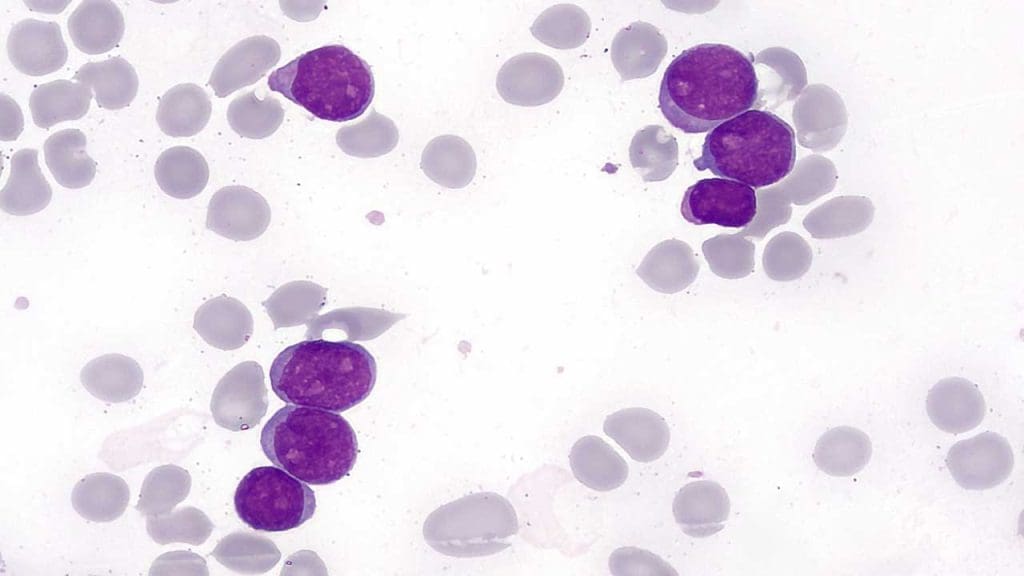

- Peripheral Blood Smear: The hallmark is the presence of circulating myeloblasts. These are large cells with a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio and prominent nucleoli.

- Expected “Gold” Finding: Auer Rods. These are needle-like pink/red inclusions in the cytoplasm of the blasts. If you see these, it is almost certainly a myeloid process.

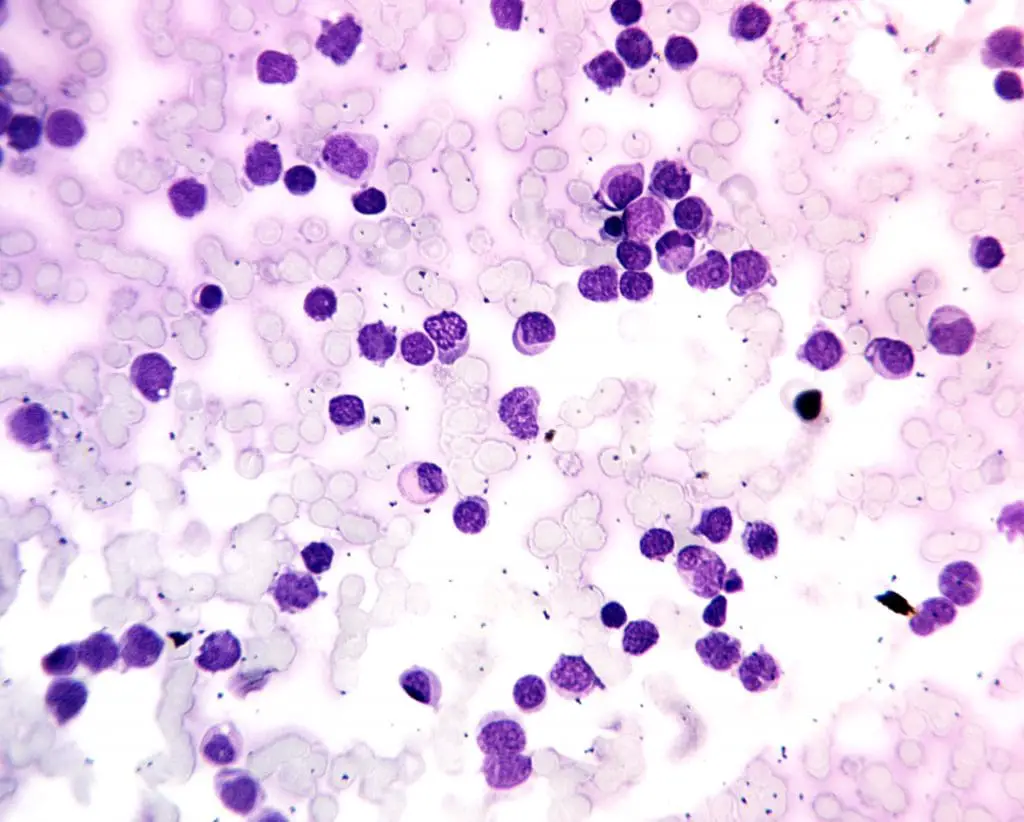

Bone Marrow Studies (The Confirmatory Test)

- Aspiration and Trephine Biopsy: This is the gold standard. The marrow is typically hypercellular (packed with cells) and must contain ≥ 20% blasts to meet the traditional WHO definition.

- Cytochemistry (Special Stains): While being replaced by flow cytometry, stains like Myeloperoxidase (MPO) or Sudan Black B are traditionally positive in AML, helping to distinguish it from ALL.

Flow Cytometry (Immunophenotyping)

This test uses lasers to identify specific proteins (antigens) on the surface of the blasts, essentially giving the leukemia an “identity card.” Positive for myeloid-associated markers such as CD13, CD33, CD117, and MPO. It also helps rule out lymphoid markers (like CD3 or CD19) to ensure it isn’t ALL.

Cytogenetics and FISH

These tests look at the structure of the chromosomes within the leukemia cells.

- Favorable: t(8;21), inv(16), or t(15;17) (the latter is specific to Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia).

- Adverse: Deletions of chromosomes 5 or 7 (-5, -7) or complex karyotypes.

Molecular Testing (Next-Generation Sequencing – NGS)

- Key Mutations to Watch For:

- FLT3-ITD: Associated with a high risk of relapse and aggressive disease.

- NPM1: Generally associated with a better response to chemotherapy.

- IDH1/IDH2: Important because we now have specific “targeted” drugs to treat these.

Summary of Diagnostic Criteria

| Investigation | Key Expected Result for AML |

| Morphology | ≥ 20% Blasts; Presence of Auer Rods |

| Flow Cytometry | Positive for CD13, CD33, CD117 |

| Cytogenetics | Recurrent translocations (e.g., t(8;21)) |

| Molecular | Mutations in NPM1, FLT3, DNMT3A |

Additional Tests

In some cases, additional tests may be performed to assess the extent of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and rule out other conditions. These may include:

- Lumbar puncture: To assess the presence of leukemic cells in the cerebrospinal fluid.

- Imaging studies: Chest X-ray, CT scans, or PET scans may be used to detect enlarged lymph nodes, bone lesions, or other manifestations of acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of AML

The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a standardized system for categorizing acute myeloid leukemia (AML) subtypes based on their genetic and morphological characteristics. This classification is essential for guiding treatment decisions, prognostication, and monitoring disease progression.

The 5th Edition of the WHO Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours (2022) represents a landmark shift in how we define AML. The most significant change is the transition from a morphology-based system (looking at cells) to a genetically-driven system (looking at DNA).

In this new framework, the “20% blast rule” has been de-emphasized for many subtypes, acknowledging that the underlying biology of the disease is more important than the arbitrary number of blasts in the marrow.

AML with Defining Genetic Abnormalities

In the 2022 update, if a patient has specific “defining” genetic mutations, they are diagnosed with AML regardless of the blast percentage (with a few exceptions). This recognizes that these genetic hits are the true drivers of the disease.

- Established Entities: Includes classic translocations like t(8;21), inv(16), and t(15;17) (APL).

- Newer Entities: Now includes specific categories for:

- AML with KMT2A rearrangement (formerly MLL).

- AML with MECOM rearrangement.

- AML with NUP98 rearrangement.

- AML with NPM1 mutation: Diagnosis can be made with <20% blasts.

- AML with CEBPA mutation: Specifically requiring in-frame bZIP mutations.

AML Defined by Differentiation

This category replaces the old “AML Not Otherwise Specified (NOS).” It is reserved for cases that do not have any of the defining genetic abnormalities listed above. These are still diagnosed based on the ≥ 20% blast threshold and are categorized by their appearance:

- AML with minimal differentiation.

- AML without maturation.

- AML with maturation.

- Acute basophilic leukemia.

- Acute myelomonocytic/monocytic leukemia.

- Pure erythroid leukemia (PEL).

AML, Myelodysplasia-Related (AML-MR)

This category replaces “AML with myelodysplasia-related changes (MRC).” The 2022 classification has moved away from relying solely on visual “dysplasia” (odd-looking cells) and now prioritizes a specific set of 8 mutations (e.g., ASXL1, BCOR, EZH2, SF3B1, U2AF1) and cytogenetic abnormalities (like complex karyotypes or -7).

Key Change: We no longer need a history of MDS to be in this category; if the genetic “signature” of myelodysplasia is present, it is classified as AML-MR.

The Blast Threshold Shift

| Subtype | 2022 Blast Threshold for Diagnosis |

| AML with Defining Genetics (e.g., NPM1, t(8;21)) | Any blast % (except BCR::ABL1 and CEBPA) |

| AML Defined by Differentiation | ≥ 20% |

| AML-MR (Myelodysplasia-related) | ≥ 20% |

| AML with BCR::ABL1 | ≥ 20% (to distinguish from CML blast crisis) |

French-American-British (FAB) Classification

The French-American-British (FAB) classification of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), developed in the 1970s, was the first widely accepted system for categorizing acute myeloid leukemia (AML) subtypes based on their morphological characteristics. This classification was based on the microscopic appearance of blast cells, the immature myeloid cells that are the hallmark of acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The FAB classification divided acute myeloid leukemia (AML) into eight subtypes, designated as M0 to M7, based on the degree of maturation and differentiation of the blast cells.

FAB Classification Subtypes

- M0: Minimal differentiation AML. M0 has blasts with CD13+, CD33+, CD11b+, CD11c+, Cd14+ and CD15+. The cells have no clear evidence of cellular maturation and cytochemical stains MPO and Sudan Black B are negative.

- M1: Myeloblastic AML without maturation. M1 is close to M0 in terms of surface markers but the blasts have Auer rods and usually give positive results with MPO and SBB stains and CD13, 33 and CD117 positive.

- M2: Myeloblastic AML with maturation. M2 has greater than 20% blasts, at least 10 % maturing cells of neutrophil lineage and fewer than 20% precursors with monocytic lineage. Auer rods and other aspects of dysplasia are present. MPO and SBB stains positive with CD13 and CD15+.

- M3: Promyelocytic AML (APL). M3 has promyelocytes with abundant and intensely azurophilic granulations. The nucleus is usually monocytic in appearance and immunophenotyping reveals CD13 and CD33+ while HLA-DR and CD34-.

- M4: Myelomonocytic AML. M4 is characterized by a significantly elevated WBC count and the presence of myeloid and monocytoid cells in the peripheral blood and bone marrow. Monocytic cells consisting of monoblasts and promonocytes constitute at least 20% of all marrow cells. The cells are positive for myeloid antigens CD13 and CD33 and the monocytic antigens CD14, CD4, CD11b, CD11c, CD64 and CD36.

- M5: Monocytic AML. Acute monoblastic and monocytic leukaemias are based on the degree of maturity of the monocytic cells present in the marrow and peripheral blood, more than 80% of the marrow cells are of monocytic origin. It has 2 subtypes, the M5a acute monoblastic leukemia and M5b the acute monocytic leukemia. These cells are CD14+, CD4+, CD11b+, CD11c+, CD36+, CD64+ and CD68+. Nonspecific esterase tests are usually positive. This is the most common acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in younger individuals.

- M6: Erythroleukemic AML. Acute erythroid leukemia involves RBC precursors with significant dysplastic features such as multinucleation, megaloblastoid asynchrony and vacuolization. The nucleated RBCs in the peripheral blood may account for more than 50% of the total number of nucleated cells. The immunophenotyping reveals CD13, CD33, CD15, glycophorin A and glycophorin C positive cells.

- M7: Megakaryocytic AML. Patients usually have cytopenias, although some may have thrombocytosis. Dysplastic features are often present in all cell lines. Diagnosis requires the presence of at least 20% blasts of which at least 50% must be of megakaryocytes origin. Megakaryoblasts are identified by immunostaining and employing antibodies specific for cytoplasmic von Willebrand factor or platelet membrane antigens CD41, CD42b or CD61.

| FAB subtypes | Morphology | Immunopheno-typing | |

| M0 | Minimally differentiated AML | Medium-sized blasts with rounded nucleus and prominent nucleolus. Basophilic agranular cytoplasm | +: 13, 33, 11b, 11c, 14, 15 |

| M1 | AML without maturation | Medium-sized blasts with rounded nucleus and prominent nucleolus. Fine azurophilic granulation or Auer rods in cytoplasm. | +: MPO, 13, 33, 117 +/-: CD34 |

| M2 | AML with maturation | Small to medium-sized blasts with rounded nucleolus. Primary azurophilic granulation or Auer rods in basophilic cytoplasm. | +: MPO, Sudan Black, 13, 15 +/-: CD34, HLA-DR, CD117 |

| M3 | Promyelocytic leukemia | Irregular or bilobed with a deep cleft monocytic-like nucleus. Abundance of deep-staining azurophilic granulation. | +: CD13, CD33 -: CD34, HLA-DR |

| M4 | Acute myelomonocytic leukemia | Large blasts with rounded, kidney-shaped or irregular nucleus and prominent nucleoli. There is variable basophilia. | +: CD13, CD15, CD33, CD11b, CD11c, CD14, CD64, CD4 |

| M5a | Acute monoblastic leukemia | Large blasts with rounded nucleus and 1-3 nucleoli. Moderately large and deep basophilic cytoplasm with occasional Auer rods. | +: CD14, CD4, CD64, CD68, CD11c, HLA-DR |

| M5b | Acute monocytic leukemia | Promonocytes with a rounded or kidney-shaped nucleus. Slightly basophilic granulated cytoplasm with some vacuoles. | |

| M6a | Acute erythroid leukemia with proliferation of mixed blasts | >50% erythroid precursors and ~30% myeloblasts with dyserythropoiesis. | +: CD13, CD33, CD15, Glycophorin A, Glycophorin C |

| M6b | Pure erythroid leukemia | ~80% erythroid precursors and <3% myeloid cells with dyserythropoiesis. | |

| M7 | Acute megakaryocytic leukemia | Variably sized megakaryoblasts with round or indented nucleus and 1 – 3 prominent nucleoli. Agranular, basophilic cytoplasm with pseudopod formation. Platelet dysplasia seen in peripheral blood. | +: CD41, CD61, CD42, CD13, CD33, CD34 |

Limitations of the FAB Classification

While the FAB classification provided a valuable framework for understanding acute myeloid leukemia (AML) subtypes, it had several limitations:

- It relied solely on morphological criteria, which can be subjective and vary among different observers.

- It did not account for genetic abnormalities, which play a crucial role in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) classification and treatment planning.

- It did not adequately distinguish between acute myeloid leukemia (AML) subtypes with different clinical outcomes.

Replacement of the FAB Classification

The FAB classification was largely replaced by the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in 2001. The WHO classification incorporated genetic and molecular information alongside morphological criteria, providing a more comprehensive and clinically relevant system for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) classification. However, the FAB classification remains a historical landmark in the development of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) classification and continues to be used in some settings.

WHO 2022 vs FAB Classifications Summary

| Feature | FAB Classification (Historical) | WHO Classification (2022 – 5th Ed) |

| Primary Basis | Morphology & Cytochemistry: Based on how cells look under a microscope and how they stain (e.g., MPO, NSE). | Genetics & Molecular Profiling: Based on DNA mutations and chromosomal translocations. |

| Blast Threshold | Requires ≥ 30% blasts in the bone marrow or blood. | Usually ≥ 20%, but no threshold is required for defining genetic abnormalities (e.g., NPM1 or t(8;21)). |

| Subtyping | Categorized into M0 through M7 based on the lineage and degree of maturation. | Categorized into “Defining Genetic Abnormalities” or “Defined by Differentiation.” |

| Genetic Focus | Mostly ignored; genetics were not well understood when FAB was created (1970s). | Central: Genetics determine the diagnosis, even if the cells look like a different FAB subtype. |

| Clinical Use | Used today mainly as a shorthand for cell appearance (e.g., “It looks like an M5”). | Used for Risk Stratification and choosing Targeted Therapies. |

| Special Categories | None; all cases were forced into M0-M7. | Includes specific categories for Myelodysplasia-Related (AML-MR) and Prior Cytotoxic Therapy. |

Mapping FAB Morphology to WHO 2022 Entities

| FAB Category | Morphological Description | Modern WHO 2022 Context |

| M0 | Undifferentiated | AML defined by differentiation (minimal) |

| M1 | Minimal maturation | AML defined by differentiation (without maturation) |

| M2 | With maturation | Often correlates with t(8;21) (AML with RUNX1::RUNX1T1) |

| M3 | APL (Promyelocytic) | APL with PML::RARA (A medical emergency) |

| M4 / M5 | Monocytic / Myelomonocytic | Often associated with KMT2A or NPM1 mutations |

| M6 | Erythroleukemia | Now classified as Pure Erythroid Leukemia (PEL) |

| M7 | Megakaryoblastic | Associated with GATA1 (Down Syndrome) or t(1;22) |

Treatment and Management of AML

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a rapidly progressing and aggressive form of blood cancer, requires prompt and intensive treatment to eradicate leukemic cells and restore normal blood cell production. The management of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is no longer a “one-size-fits-all” approach but a highly personalized strategy dictated by genomic profiling and patient fitness.

Risk Stratification and the “Genomic First” Approach

Before therapy begins, rapid genomic testing (NGS) is essential. Treatment is now guided by the European LeukemiaNet (ELN) 2022/2026 recommendations, which categorize patients into Favorable, Intermediate, or Adverse risk groups based on mutations like NPM1, FLT3-ITD, IDH1/2, TP53, and KMT2A.

Phase I: Induction Therapy

The goal of induction is to achieve Complete Remission (CR), defined as <5% blasts in the bone marrow and recovery of peripheral blood counts.

A. Intensive Induction (“7+3” Backbone)

For fit, younger patients, the traditional “7+3” regimen (7 days of Cytarabine + 3 days of an Anthracycline like Daunorubicin) remains the standard, but it is now frequently “augmented”:

- FLT3+ AML: Addition of Midostaurin or Quizartinib.

- CD33+ AML: Addition of Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin (an antibody-drug conjugate).

- Secondary AML (t-AML): Use of CPX-351, a liposomal formulation of Daunorubicin/Cytarabine that improves survival in high-risk secondary AML.

B. Non-Intensive Induction (VenAza)

For patients over 75 or those with significant comorbidities, the combination of Venetoclax (a BCL-2 inhibitor) and a Hypomethylating Agent (Azacitidine or Decitabine) has become the global standard. This “chemo-light” approach often produces response rates comparable to intensive chemotherapy with significantly less toxicity.

C. Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia (APL)

APL is treated as a distinct entity. The gold standard is a chemotherapy-free regimen of All-trans Retinoic Acid (ATRA) and Arsenic Trioxide (ATO), which achieves cure rates >95% in low-to-intermediate risk patients.

Targeted Therapies and Emerging Frontiers

Specific inhibitors are used both in the frontline and relapsed/refractory (R/R) settings:

- IDH1/IDH2 Inhibitors: Ivosidenib (IDH1) and Enasidenib (IDH2) bypass the differentiation block in leukemic cells.

- Menin Inhibitors: Revumenib (approved Oct 2025) is a major breakthrough for patients with NPM1 mutations or KMT2A rearrangements, offering a targeted oral option for previously difficult-to-treat subgroups.

Phase II: Consolidation and Maintenance

Once complete remission is achieved, consolidation therapy is required to eliminate Measurable Residual Disease (MRD).

- Chemotherapy: High-dose Cytarabine (HiDAC) for favorable-risk patients.

- Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplant (allo-HCT): The definitive curative option for intermediate and adverse-risk patients.

- Maintenance Therapy: Oral Azacitidine is now standard for patients in CR who cannot proceed to transplant, extending overall survival.

Supportive Care: Managing Oncologic Emergencies

Managing the “side effects” of rapid cell kill is as important as the chemotherapy itself.

Tumor Lysis Syndrome (TLS)

TLS occurs when leukemic cells die rapidly, releasing potassium, phosphate, and uric acid into the blood.

- Prophylaxis: Aggressive IV hydration (3L/m²) and Allopurinol.

- Treatment: Rasburicase for high-risk patients or those with elevated uric acid to prevent acute kidney injury.

Differentiation Syndrome (DS)

A unique complication of ATRA, ATO, and IDH/Menin inhibitors.

- Symptoms: Fever, weight gain, dyspnea, and pulmonary infiltrates.

- Management: Prompt initiation of high-dose corticosteroids (Dexamethasone 10mg BID) at the first sign of respiratory distress, even before confirming the diagnosis.

Monitoring: The Role of MRD

Management is now MRD-driven. Using flow cytometry or PCR to detect 1 leukemic cell in 10,000, clinicians decide whether to escalate to transplant or continue with maintenance. Persistent MRD-positivity is considered a “molecular relapse” and often triggers a change in therapy before clinical symptoms appear.

The “Iceberg” Analogy

Traditional remission (Complete Remission or CR) is defined by looking through a microscope and seeing <5% blasts. However, the microscope is relatively “blind.”

- Morphologic Remission: You only see the tip of the iceberg above the water (<5 cells in 100).

- MRD: Detects the massive part of the iceberg hidden underwater, the leukemic cells that are present at a frequency of 1 in 1,000, 1 in 10,000, or even 1 in 1,000,000.

Clinical Significance: The “Remission Depth”

MRD is the single best predictor of relapse.

- MRD-Negative: Associated with significantly longer Overall Survival (OS) and a much lower chance of the leukemia returning.

- MRD-Positive: Even if the patient looks “fine” under the microscope, MRD positivity after induction is a “warning light.” It often suggests that the current chemotherapy isn’t enough and the patient likely needs a Stem Cell Transplant.

has specific strengths and sensitivities.

| Method | Sensitivity | Best Use Case | Pros/Cons |

| Flow Cytometry (MFC) | 10-3 to 10-4 | Patients without a specific DNA error. | Pros: Fast (24h), widely available. Cons: Requires expert “pattern recognition.” |

| qPCR / dPCR | 10-4 to 10-6 | Gold Standard for NPM1 and Core-Binding Factor (t(8;21), inv(16)). | Pros: Extremely sensitive. Cons: Only works if you have a specific “target” gene. |

| NGS (Next-Gen Seq) | 10-5 to 10-6 | Broad screening for multiple mutations (e.g., FLT3-ITD, IDH). | Pros: Highly specific. Cons: Slower; must distinguish cancer from CHIP (age-related mutations). |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the life expectancy of someone with acute myeloid leukemia?

According to the National Cancer Institute, the 5-year relative survival rate for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is 29.3%.

Is acute myeloid leukemia curable?

Around two-thirds (60-70%) of adults with AML can achieve complete remission (CR) after initial treatment (induction therapy). Among those who achieve CR, over one-quarter (more than 25%) have a good chance of surviving for at least 3 years, potentially achieving a cure. However, a relapse is a possibility.

What causes acute myeloid leukemia?

The exact cause of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is not fully understood, but it is known to involve genetic mutations in bone marrow cells. These mutations cause the cells to grow and divide uncontrollably, eventually crowding out healthy blood cells. There are some risk factors that can increase the chances of developing AML that have been discussed in the article above.

What are warning signs of leukemia?

While there is no single definitive warning sign, some common symptoms that might indicate leukemia include:

- Fatigue: This is the most common symptom and can be persistent, not improving with rest.

- Frequent infections: Due to abnormal white blood cells, individuals with leukemia are more prone to infections that are frequent, severe, or last longer than usual.

- Easy bruising and bleeding: This occurs because abnormal blood cells may not function properly in forming clots, leading to easy bruising and bleeding.

- Fever or chills: Unexplained fever or chills can be a sign of infection or underlying conditions like leukemia.

- Unexplained weight loss: Weight loss without trying can be a warning sign of various conditions, including leukemia.

- Shortness of breath: This can occur due to anemia, a common complication of leukemia where the blood lacks enough red blood cells to carry oxygen effectively.

- Pale skin: This can be a sign of anemia, as the body doesn’t have enough red blood cells to deliver oxygen throughout the body.

- Swollen lymph nodes: Lymph nodes are part of the immune system and may swell in response to infection or due to leukemia itself.

- Enlarged spleen or liver: These organs may become enlarged in response to leukemia.

- Bone or joint pain: This can be caused by infiltration of leukemia cells in the bones or by low blood cell counts.

It’s important to understand that these symptoms can also be caused by other medical conditions.

What are the 5 stages of acute myeloid leukemia?

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) doesn’t have a traditional staging system like some other cancers. This is because AML doesn’t typically form tumors, and staging is often based on tumor size and spread.

Instead of stages, doctors use various terms to describe AML and its progression, including:

- Untreated: This refers to newly diagnosed AML before any treatment begins.

- Active disease: This indicates the presence of active leukemia cells, typically defined as having more than 5% blasts (immature blood cells) in the bone marrow.

- Remission: This signifies the absence of detectable leukemia cells after treatment. There are different levels of remission, such as complete remission (CR) where no blasts are found in the blood or bone marrow, and partial remission where some blasts may be present but significantly reduced.

- Measurable residual disease (MRD): This refers to the presence of minimal amounts of leukemia cells even in remission, detectable through very sensitive tests.

- Relapsed: This occurs when leukemia returns after a period of remission.

Can lifestyle cause leukemia?

Lifestyle choices do not directly cause acute myeloid leukemia (AML). However, certain lifestyle factors can increase the risk of developing AML.

- Smoking: Smokers have a higher risk of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) compared to non-smokers. The specific chemicals in cigarettes are thought to damage the DNA in bone marrow cells, potentially leading to the mutations that cause AML.

- Exposure to certain chemicals: Long-term exposure to benzene (found in gasoline, some dyes, and certain plastics) and other specific chemicals like herbicides and benzene derivatives has been linked to an increased risk of AML. It’s crucial to follow safety guidelines and use appropriate protection when handling such chemicals.

- Radiation exposure: High doses of radiation exposure, such as from atomic bombs or certain medical treatments, can increase the risk of AML.

Even with these risk factors, most people will not develop AML. Additionally, many individuals with AML have no established risk factors, highlighting the complex and not fully understood nature of the disease.

Can leukemia come on suddenly?

Yes, acute leukemia, including acute myeloid leukemia (AML), can come on suddenly within days or weeks. This is because the abnormal white blood cells in acute leukemia multiply rapidly, causing symptoms to develop quickly. These symptoms can often mimic those of the flu, such as:

- Fatigue

- Fever

- Frequent infections

- Easy bruising and bleeding

Chronic leukemia, on the other hand, typically progresses gradually and may not cause any noticeable symptoms in the early stages. Symptoms like fatigue and weight loss might only become evident as the disease progresses.

Can AML run in families?

AML, or acute myeloid leukemia, can run in families in some rare cases, but it is not generally considered a hereditary disease.

Most cases of AML are not hereditary

- The majority of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cases (around 90%) are not caused by inherited gene mutations. These cases are thought to arise from spontaneous mutations that occur during a person’s lifetime, potentially due to factors like environmental exposures or random errors during cell division.

However, there are some exceptions

- In rare instances, acute myeloid leukemia (AML) can be linked to inherited genetic mutations or specific genetic syndromes. These mutations or syndromes can increase an individual’s risk of developing AML.

- Examples of such syndromes include Down syndrome, Fanconi anemia, and Li-Fraumeni syndrome.

- Certain inherited gene mutations, such as those in the GATA2, ETV6, CEBPA, and RUNX1 genes, have also been associated with a higher risk of AML.

Family history can be a factor, but not always

- Having a close relative (parent, sibling) with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) can slightly increase your risk of developing the disease. However, this risk is still relatively low, and most people with a family history of AML will not develop it themselves.

- It’s important to remember that family history can also be due to shared environmental factors within the family, not necessarily through inherited genes.

Is AML painful?

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) itself does not directly cause pain, but some symptoms and complications associated with AML can be painful.

No direct pain from AML

- AML affects the blood and bone marrow, not directly causing pain in tissues or organs.

Painful symptoms and complications

- Bone or joint pain: This can be a common acute myeloid leukemia (AML) symptom in some patients, caused by the abnormal growth of leukemia cells in the bone marrow, putting pressure on nerves or causing inflammation. The pain can be dull or sharp and may worsen at certain times.

- Mouth sores and inflammation: These can cause discomfort and pain, especially during eating or speaking.

- Swollen lymph nodes: While not always painful, enlarged lymph nodes due to acute myeloid leukemia (AML) can sometimes cause discomfort or pressure in the affected area.

- Infections: Individuals with AML are more prone to infections due to compromised immune function. These infections themselves can cause pain in various locations depending on the type and location of the infection.

Does AML spread quickly?

Yes, acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is generally considered to be an aggressive cancer that can spread quickly within the body.

How does acute myeloid leukemia cause death?

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) can be fatal, and the cause of death depends on various factors like the severity of the disease, response to treatment, and complications that arise. Here are some of the ways AML can lead to death:

- Infections: AML disrupts the production of healthy white blood cells, which are crucial for fighting infections. This weakened immune system makes individuals with acute myeloid leukemia (AML)more susceptible to serious infections. These infections can be bacterial, fungal, or viral and can overwhelm the body, potentially leading to organ failure and death.

- Bleeding complications: AML can affect the production of platelets, which are necessary for blood clotting. This can lead to easy bruising, bleeding, and uncontrolled internal bleeding. Severe bleeding, especially in critical areas like the brain, can be life-threatening.

- Organ failure: The infiltration of abnormal leukemia cells can damage various organs, including the liver, lungs, and kidneys. This damage can eventually lead to organ failure, which can be fatal.

- Progression of the disease: In some cases, despite treatment, AML can progress and become resistant to therapy. This uncontrolled growth of leukemia cells can ultimately lead to death.

These are some of the possible causes of death in acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and the specific course of the disease can vary from person to person. Early diagnosis and aggressive treatment are crucial to improve the chances of successful treatment and minimize the risk of complications that can be fatal.

What is the significance of the NPM1 mutation in AML?

The NPM1 mutation is one of the most common genetic alterations in acute myeloid leukemia (AML). When present without an FLT3-ITD mutation, it is generally associated with a “favorable” prognosis and a higher likelihood of responding well to standard chemotherapy.

How does AML differ from MDS (Myelodysplastic Syndrome)?

MDS is a “pre-leukemic” condition characterized by ineffective blood cell production and dysplasia, but with fewer than 20% blasts. Once the blast count reaches 20% (or specific mutations are found), it is classified as acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

Can AML be diagnosed without a bone marrow biopsy?

While a peripheral blood smear showing >20% blasts can strongly suggest acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a bone marrow biopsy remains the “gold standard” to perform the necessary cytogenetic and molecular testing required for accurate classification and treatment planning.

What is “7+3” Induction Chemotherapy?

This is the traditional standard treatment for fit patients, consisting of a 7-day continuous infusion of Cytarabine and a 3-day injection of an Anthracycline (like Daunorubicin).

What is the role of a Stem Cell Transplant in AML?

An allogeneic stem cell transplant is typically used during “Consolidation” for patients with intermediate or high-risk acute myeloid leukemia (AML) to replace the diseased marrow with healthy donor cells and provide a “graft-versus-leukemia” effect.

Glossary of Related Medical Terms

- Auer Rods: Needle-like clumps of azurophilic granular material found in the cytoplasm of myeloblasts; pathognomonic for AML.

- Blast Crisis: A phase where more than 20% of the blood or bone marrow is composed of immature blast cells.

- Clonal Hematopoiesis (CHIP): The presence of a growing population of blood cells derived from a single mutated stem cell, often a precursor to AML.

- Cytogenetics: The study of chromosomal structure and abnormalities (e.g., translocations, deletions).

- Differentiation Arrest: A hallmark of AML where blood cells stop maturing and remain in an immature, non-functional “blast” state.

- Epigenetic Modifiers: Drugs or mutations that change how genes are turned on or off without changing the DNA sequence itself.

- Hyperleukocytosis: An extremely high white blood cell count (usually >100,000/µL) that can lead to leukostasis.

- Leukostasis: A medical emergency where “sticky” blasts plug small blood vessels, causing respiratory or neurological distress.

- Pancytopenia: A simultaneous decrease in red cells, white cells, and platelets.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Hwang SM. Classification of acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Res. 2020 Jul 31;55(S1):S1-S4. doi: 10.5045/br.2020.S001. PMID: 32719169; PMCID: PMC7386892.

- Döhner H, Wei AH, Appelbaum FR, Craddock C, DiNardo CD, Dombret H, Ebert BL, Fenaux P, Godley LA, Hasserjian RP, Larson RA, Levine RL, Miyazaki Y, Niederwieser D, Ossenkoppele G, Röllig C, Sierra J, Stein EM, Tallman MS, Tien HF, Wang J, Wierzbowska A, Löwenberg B. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2022 recommendations from an international expert panel on behalf of the ELN. Blood. 2022 Sep 22;140(12):1345-1377. doi: 10.1182/blood.2022016867. PMID: 35797463.

- Ishii H, Yano S. New Therapeutic Strategies for Adult Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancers (Basel). 2022 Jun 5;14(11):2806. doi: 10.3390/cancers14112806. PMID: 35681786; PMCID: PMC9179253.

- Kantarjian, H., Kadia, T., DiNardo, C. et al. Acute myeloid leukemia: current progress and future directions. Blood Cancer J. 11, 41 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-021-00425-3.

- Sekeres MA. When Blood Breaks Down: Life Lessons from Leukemia (Mit Press). 2021

- Bhushan B. AML (Acute Myeloid Leukemia): A survival guide for patients. 2021.

- Greiner J. Immunotherapies for Acute Myeloid Leukemia (MDPI AG). 2020.

- Röllig C, Ossenkoppele GJ.Acute Myeloid Leukemia (Hematologic Malignancies) (Springer). 2021.

- National Cancer Institute. Acute Myeloid Leukemia Treatment (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version

- Khoury, J.D., Solary, E., Abla, O. et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Myeloid and Histiocytic/Dendritic Neoplasms. Leukemia 36, 1703–1719 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-022-01613-1.

- Park H. S. (2024). What is new in acute myeloid leukemia classification?. Blood research, 59(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44313-024-00016-8.

- Platzbecker, U., Larson, R. A., & Gurbuxani, S. (2025). Diagnosis and treatment of AML in the context of WHO and ICC 2022 classifications: Divergent nomenclature converges on common therapies. HemaSphere, 9(2), e70083. https://doi.org/10.1002/hem3.70083