TL;DR

Systemic comprehensive approach to anemia ensures thorough evaluation, leading to an accurate diagnosis and the most appropriate treatment plan for the specific type of anemia. It also avoids unnecessary investigations and treatments, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Detailed Clinical History ▾

- Explore presenting illness (symptoms, onset, duration, severity).

- Investigate menstrual history (regularity, bleeding amount) for women.

- Review past medical, surgical, and drug history.

- Assess social history (occupation, travel, tobacco/alcohol use, socioeconomic status).

- Gather information on dietary habits and supplement use.

- Explore family history for anemia or relevant conditions.

Physical Examination ▾

- Look for signs of pallor, jaundice, koilonychia (spoon-shaped nails).

- Assess vital signs for low blood pressure, tachycardia, or tachypnea.

- Examine skin, lymph nodes, head and neck, cardiovascular system, respiratory system, abdomen, and musculoskeletal system.

- Perform neurological examination (if vitamin B12 deficiency is suspected).

Laboratory Investigations ▾

- Complete Blood Count (CBC)

- Peripheral Blood Smear

- Iron Studies

- Vitamin B12 and Folate Levels

- Additional Tests (as needed)

Differential Diagnosis ▾

Based on clinical findings and laboratory tests, healthcare professionals create a list of possible causes of anemia based on the MCV value (microcytic, normocytic, macrocytic).

Treatment ▾

The approach emphasizes treating the underlying cause of anemia. This can involve iron supplementation, vitamin B12 injections, blood transfusions, or managing chronic diseases that contribute to anemia.

*Click ▾ for more information

Introduction

A systemic approach to anemia is a comprehensive strategy that tackles the condition from multiple angles, aiming for accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and long-term management. It involves several steps that consider various factors to pinpoint the underlying cause and implement the most effective treatment.

- Detailed History and Physical Examination: This initial step gathers information about the patient’s symptoms, medical history, dietary habits, medications, and family history. The physical examination looks for signs of pallor, jaundice, and other potential clues related to the cause of anemia.

- Laboratory Investigations: A battery of blood tests forms the backbone of diagnosing anemia. These tests include:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): Measures hemoglobin, hematocrit, RBC count, MCV, MCH, MCHC, and RDW. The values in these tests help differentiate between different types of anemia (microcytic, normocytic, macrocytic).

- Peripheral Blood Smear: Provides a visual assessment of red blood cell morphology, revealing abnormalities like microcytosis or macrocytosis that can point towards specific causes.

- Iron Studies: Serum iron, ferritin, transferrin saturation, and TIBC help diagnose iron deficiency anemia.

- Vitamin B12 and Folate Levels: Assessed to identify deficiencies contributing to anemia.

- Additional Tests (as needed): Reticulocyte count, coagulation studies, kidney function tests, stool tests for occult blood loss, and hemoglobin electrophoresis may be employed depending on the suspected cause.

- Differential Diagnosis: Based on the findings from history, physical examination, and lab tests, doctors create a differential diagnosis list. This list includes all the possible causes of anemia that fit the patient’s presentation. The MCV value from the CBC plays a crucial role here, directing the investigation towards microcytic, normocytic, or macrocytic causes.

- Targeted Investigations: Once the differential diagnosis narrows down, further specific tests may be ordered to confirm a particular cause. For example, hemoglobin electrophoresis helps diagnose hemoglobinopathies like thalassemia.

- Treatment: The systemic approach emphasizes treating the underlying cause of anemia. This could involve iron supplementation for iron deficiency, vitamin B12 injections for deficiency, or medications to manage chronic diseases contributing to anemia. In severe cases, blood transfusions might be necessary.

- Monitoring and Management: After initiating treatment, doctors monitor the patient’s progress through regular blood tests. This helps assess the effectiveness of treatment and make adjustments as needed.

A systemic approach ensures a thorough evaluation, leading to an accurate diagnosis and the most appropriate treatment plan for the specific type of anemia. This approach not only improves patient outcomes but also avoids unnecessary investigations and treatments.

Detailed Clinical History

History of Presenting Illness (HOPI)

- Onset and Duration: When did the patient first notice symptoms like fatigue, weakness, or shortness of breath? How long have these symptoms persisted?

- Severity and Progression: Have the symptoms worsened over time? Are there any specific activities that exacerbate the symptoms?

- Associated Symptoms: Does the patient experience dizziness, headache, pale skin, palpitations, chest pain, difficulty sleeping, or changes in appetite?

- Blood Loss: Has the patient experienced any recent or ongoing blood loss (heavy menstrual periods, gastrointestinal bleeding, trauma)?

Menstrual History

- Regularity and Duration of Cycle: Are periods regular or irregular? How many days do they typically last?

- Menstrual Flow: Is the flow heavy, moderate, or light? Has there been any recent increase in blood flow during periods?

- Past Use of Hormonal Contraception: This information can be relevant for potential iron deficiency.

Past Medical, Surgical and Drug History

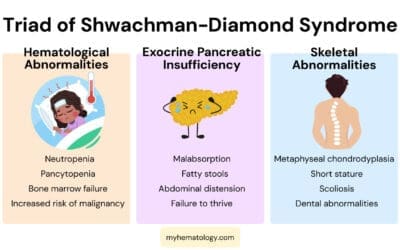

- Past Diagnoses: Does the patient have any chronic medical conditions like kidney disease, autoimmune disorders, or inflammatory bowel disease?

- Previous Surgeries: Have they undergone any surgeries that could have caused blood loss or affected nutrient absorption?

- Medications: Current and past medications, including over-the-counter drugs and supplements. Certain medications can suppress bone marrow function or interfere with iron absorption, potentially leading to anemia.

Social History

- Occupation and Work Environment: Exposure to toxins like lead can contribute to anemia.

- Travel History: Recent travel to areas with malaria or other infections can be a risk factor.

- Alcohol and Tobacco Use: Excessive alcohol intake can contribute to anemia, while smoking can mask symptoms.

- Socioeconomic Status: Access to nutritious food and healthcare can influence anemia risk.

Dietary Habits

- Dietary Pattern: A detailed dietary evaluation is essential. Does the patient consume a balanced diet rich in iron, vitamin B12, and folate? Are there any dietary restrictions or limitations?

- History of Pica: Craving and eating non-food items can be a sign of iron deficiency.

Medication and Family History

- Over-the-counter Medications: Explore regular use of aspirin or other medications that might contribute to blood loss.

- Family History: Is there a family history of anemia, thalassemia, or other blood disorders?

By gathering this detailed clinical history, healthcare professionals can gain valuable insights into potential causes of anemia. This information, combined with physical examination and laboratory investigations, helps build a comprehensive picture and guides the diagnostic process towards the most likely cause.

Epidemiology of Anemia

Understanding the epidemiology of anemia helps identify individuals at higher risk and guide appropriate screening strategies.

Age and Sex Predilection

- Iron Deficiency Anemia (IDA): Most common globally, affecting:

- Children: Particularly prevalent in preschoolers due to rapid growth, inadequate iron intake, and potential blood loss from parasitic infections.

- Pregnant Women: Increased iron demands during pregnancy put them at risk, especially with inadequate dietary intake or multiple pregnancies.

- Adolescent Girls and Women of Reproductive Age: Heavy menstrual bleeding is a significant risk factor.

- Vitamin B12 and Folate Deficiency Anemia: More common in older adults due to:

- Reduced dietary intake and absorption issues.

- Use of medications that interfere with B12 absorption (metformin, proton pump inhibitors).

- Anemia of Chronic Disease (ACD)Anemia of Chronic Disease (ACD): Affects individuals with underlying chronic conditions like:

- Kidney disease (all age groups).

- Autoimmune diseases (more common in women).

- Cancer (all age groups).

Geographical Variations

- Iron Deficiency Anemia: More prevalent in developing countries due to:

- Poverty and limited access to iron-rich foods.

- High prevalence of parasitic infections that contribute to blood loss.

- Vitamin and Mineral Deficiencies: More common in areas with limited access to fortified foods and diverse diets.

- Infectious Diseases: Malaria, hookworm, and other chronic infections can contribute to anemia in certain regions.

- Genetic Hemoglobinopathies: Sickle cell disease and thalassemia have specific geographical distributions. Sickle cell disease has a higher prevalence in individuals of African descent. Alpha thalassemia is common in Southeast Asia and the Mediterranean. Beta thalassemia is more prevalent in the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and the Mediterranean.

Risk Factors

- Dietary Habits: Diets low in iron, vitamin B12, and folate increase the risk of deficiency anemia. Vegetarian or vegan diets without proper planning can be a risk factor.

- Medications: Certain medications can suppress bone marrow function or interfere with nutrient absorption, leading to anemia.

- Chronic Medical Conditions: Kidney disease, autoimmune disorders, and inflammatory bowel disease can contribute to anemia.

- Heavy Menstrual Bleeding: Can lead to iron deficiency anemia in women.

- Pregnancy: Increased iron demands during pregnancy put women at risk.

- Gastrointestinal Issues: Conditions like ulcers or celiac disease can impair nutrient absorption.

- Alcohol Abuse: Damages bone marrow and interferes with vitamin B12 absorption.

- Recent Surgery: Blood loss during major surgeries can contribute to anemia.

- Certain Cancers: Can suppress bone marrow function and lead to anemia.

By understanding these epidemiological factors, healthcare professionals can identify populations at higher risk for specific types of anemia.

Physical Examination

General Examination

- Appearance: Observe for signs of pallor (pale skin, mucous membranes), jaundice (yellowing of skin and whites of the eyes), koilonychia (spoon-shaped nails), which can be suggestive of certain types of anemia.

- Alertness and Orientation: Assess the patient’s mental state to rule out potential causes like vitamin B12 deficiency that can affect cognitive function.

- Demeanor: Look for signs of fatigue or weakness, common symptoms of anemia.

Vital Signs

- Weight and Height: Significant weight loss could indicate an underlying chronic illness contributing to anemia.

- Blood Pressure (BP): Low blood pressure can be a consequence of reduced oxygen delivery due to anemia.

- Pulse: Tachycardia (rapid heart rate) is a compensatory mechanism to increase blood flow to tissues in response to anemia.

- Respiratory Rate: Tachypnea (rapid breathing) may occur in severe anemia as the body tries to increase oxygen intake.

- Temperature: Fever can be a sign of infection, which can contribute to anemia of chronic disease.

Physical Examination

- Skin: Assess for pallor, icterus (jaundice), petechiae (small red spots caused by bleeding), and dryness (suggestive of malnutrition).

- Lymph Nodes: Check for enlargement, which can indicate underlying infections or malignancies.

- Head and Neck: Examine the sclerae (whites of the eyes) for signs of jaundice.

- Cardiovascular: Listen for heart murmurs, which can be a sign of heart strain due to anemia. Assess for jugular venous distention (JVD), which can be present in severe anemia due to impaired blood flow.

- Respiratory: Listen for abnormal breath sounds that could indicate lung problems contributing to anemia.

- Abdomen: Palpate the spleen (located in the left upper quadrant) to see if it’s enlarged, which can be a sign of certain types of anemia or infections.

- Musculoskeletal: Assess for muscle weakness, a common symptom of anemia.

Examination of Other Systems

- Neurological: Evaluate for signs of nerve damage, which can occur with vitamin B12 deficiency.

- Genitourinary: In women, a pelvic exam may be performed to rule out heavy menstrual bleeding as a cause of anemia.

By carefully examining different systems, healthcare professionals can identify potential causes of anemia and guide further investigations. For example, the presence of jaundice might suggest hemolytic anemia, while an enlarged spleen could be indicative of thalassemia or other conditions.

Important Note: This is not an exhaustive list, and specific aspects of the physical examination may be tailored based on the patient’s presentation and suspected cause of anemia.

Laboratory Investigations

In the systemic approach to anemia, laboratory investigations play a central role in confirming the diagnosis, identifying the underlying cause, and guiding treatment decisions.

Complete Blood Count (CBC)

This is the cornerstone of anemia evaluation. It provides valuable information on

- Hemoglobin (Hb): Measures the amount of oxygen-carrying protein in red blood cells. Low Hb levels are a hallmark of anemia.

- Hematocrit (Hct): Represents the percentage of red blood cells in whole blood. A low Hct indicates anemia.

- Red Blood Cell Count (RBC): Measures the total number of red blood cells per unit volume of blood. A low RBC count is indicative of anemia.

- Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV): Reflects the average size of red blood cells. Different MCV values can point towards specific types of anemia:

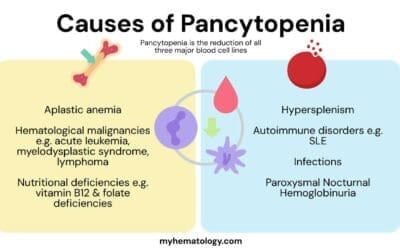

- Microcytic (MCV < 80 fL): Suggests iron deficiency anemia, thalassemia, or chronic disease anemia.

- Normocytic (MCV 80-100 fL): Can be seen in blood loss anemia, inflammatory anemia, or vitamin B6 deficiency.

- Macrocytic (MCV > 100 fL): Suggests vitamin B12 deficiency, folate deficiency, alcoholism, or liver disease.

- Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin (MCH): Represents the average amount of hemoglobin present in a single red blood cell.

- Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration (MCHC): Indicates the concentration of hemoglobin within a red blood cell.

- Red Blood Cell Distribution Width (RDW): Measures the variation in the size of red blood cells. An elevated RDW suggests a mixed type of anemia or conditions affecting red blood cell production.

Reticulocyte Count

Measures immature red blood cells released from the bone marrow. A low reticulocyte count suggests suppressed bone marrow production, while a high count indicates increased bone marrow activity in response to blood loss or hemolysis.

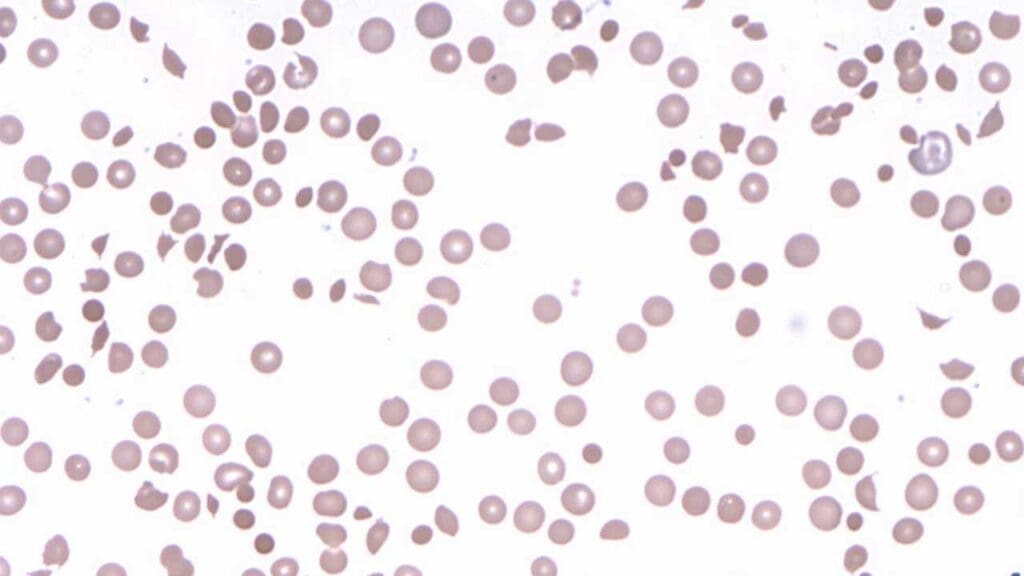

Peripheral Blood Smear

Provides a visual assessment of red blood cell morphology as an essential complement of the complete blood count.

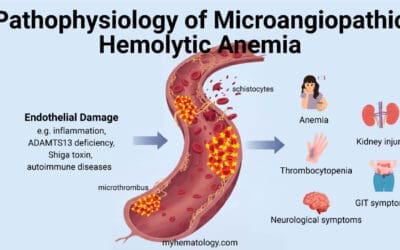

- Can reveal RBC abnormalities like:

- Microcytosis: Small red blood cells (suggestive of iron deficiency or thalassemia).

- Macrocytosis: Large red blood cells (suggestive of vitamin B12 or folate deficiency).

- Poikilocytosis: Abnormally shaped red blood cells (seen in various anemias).

- May also show the presence of abnormal white blood cells or platelets, potentially indicating underlying conditions.

Iron Studies

These tests are crucial for diagnosing iron deficiency anemia, the most common type. They include:

- Serum Iron: Measures the circulating iron levels in the blood and is low in iron deficiency.

- Ferritin: Reflects iron stores in the body. Low ferritin is a strong indicator of iron deficiency. High serum ferritin can indicate hereditary hemochromatosis.

- Transferrin Saturation: Represents the percentage of transferrin (iron-binding protein) that is saturated with iron. Elevated transferrin saturation is an indicator of hereditary hemochromatosis or sideroblastic anemia.

- Total Iron Binding Capacity (TIBC): Measures the total amount of iron that transferrin can bind. Increased TIBC can be seen in iron deficiency anemia.

Vitamin B12 and Folate Levels

- Vitamin B12: Essential for red blood cell production. Low levels suggest deficiency.

- Folate: Another crucial vitamin for red blood cell production. Deficiency can lead to anemia.

Interpretation: Low levels of either vitamin B12 or folate can cause anemia with macrocytic red blood cells on the peripheral blood smear.

Additional Investigations (as indicated by the suspected cause)

- Coagulation Studies: A valuable tool in the systemic approach to anemia when blood loss is suspected or there are underlying conditions that might affect clotting.

- Kidney Function Tests: Evaluated to rule out chronic kidney disease, which can contribute to anemia of chronic disease.

- Stool Tests for Occult Blood Loss: Can help identify hidden sources of blood loss in the digestive tract.

- Hemoglobin Electrophoresis: Separates different types of hemoglobin to diagnose hemoglobinopathies like thalassemia or sickle cell disease

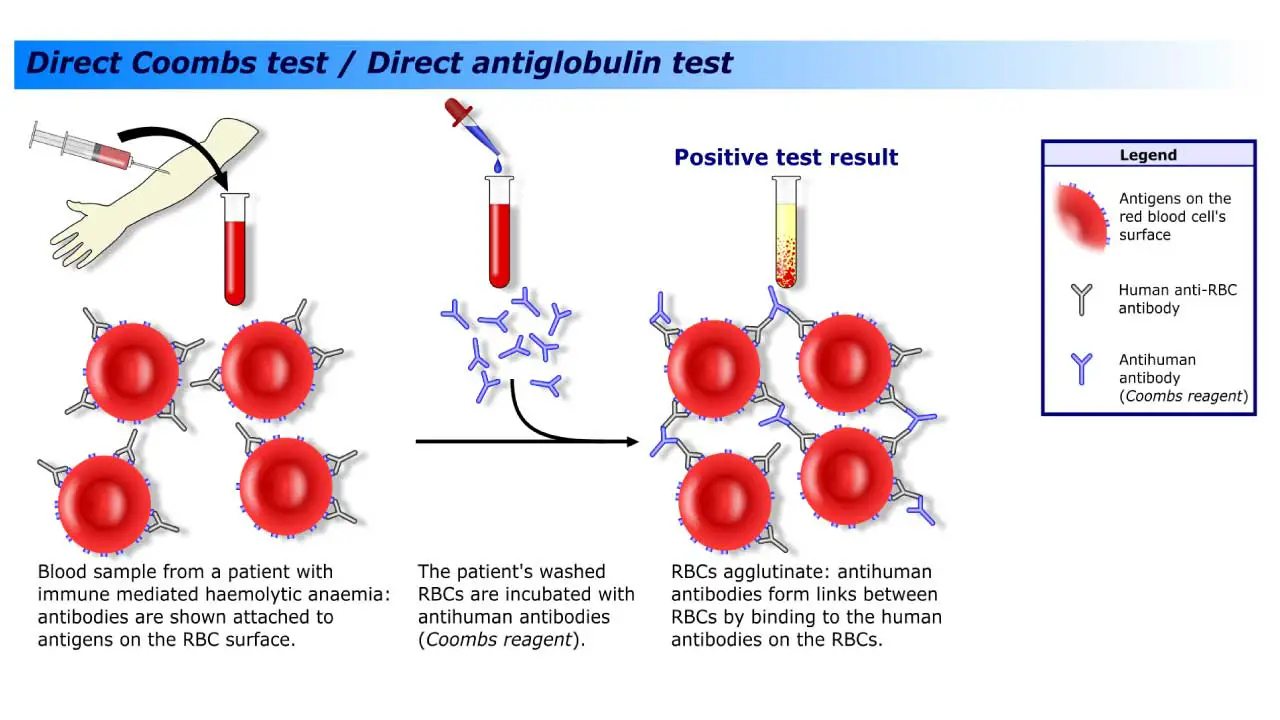

- Direct Antiglobulin Test (DAT): A valuable tool in the systemic approach to anemia, particularly hemolytic anemia. By detecting antibodies or complement on red blood cells, it helps identify immune-mediated mechanisms and guides further investigation for specific causes.

Management

Effectively managing anemia hinges on treating the underlying cause responsible for the reduction in healthy red blood cells.

Examples of Treatment for Different Causes of Anemia

- Iron Deficiency Anemia: Treatment primarily involves iron supplementation, either orally or intravenously depending on severity. Addressing the cause of iron loss, if present (e.g., heavy menstrual bleeding), is also crucial.

- Vitamin B12 and Folate Deficiency Anemia: Vitamin B12 injections or high-dose oral supplements are used for B12 deficiency. Folate deficiency is treated with folic acid supplements. Dietary modifications to increase intake of B12 and folate-rich foods may also be recommended.

- Sickle Cell Disease: There is no cure for sickle cell disease, but treatment focuses on managing symptoms and preventing complications. This can involve pain management medications, hydroxyurea (a medication that increases production of normal red blood cells), and folic acid supplementation.

- Thalassemia: Management strategies depend on the severity. In mild cases, blood transfusions and iron chelation therapy (removing excess iron from the body) may not be necessary. However, for severe thalassemia, regular blood transfusions and iron chelation therapy are crucial. Bone marrow transplants may be an option for some patients.

- Anemia of Chronic Disease: Treatment focuses on managing the underlying chronic condition (e.g., kidney disease, autoimmune disorders) that is contributing to anemia. Additionally, erythropoietin-stimulating agents (medications that stimulate red blood cell production) may be used in some cases.

- Blood Loss Anemia: The approach involves treating the source of blood loss (e.g., surgery, ulcers) and potentially replacing lost blood with blood transfusions if necessary.

By treating the underlying cause, healthcare professionals can effectively manage anemia, improve quality of life for patients, and prevent long-term complications.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Anemia: Diagnosis and Treatment (Willis, 2016).

- Management of Anemia: A Comprehensive Guide for Clinicians (Provenzano et al., 2018)

- Goldberg S, Hoffman J. Clinical Hematology Made Ridiculously Simple, 1st Edition: An Incredibly Easy Way to Learn for Medical, Nursing, PA Students, and General Practitioners (MedMaster Medical Books). 2021.