TL;DR

Menorrhagia is excessive/prolonged menstrual bleeding, significantly impacting life and often signaling underlying issues.

- Causes ▾: Primarily due to gynecological issues (fibroids, polyps) or, crucially from a hematology view, bleeding disorders (e.g., von Willebrand Disease, platelet disorders, factor deficiencies) or acquired coagulopathies.

- Symptoms ▾: Heavy bleeding (soaking pads, large clots), often with signs of anemia (fatigue, dizziness, shortness of breath), and potential personal/family history of other bleeding.

- Diagnosis (Hematology Focus) ▾: Involves detailed history, physical exam for bleeding signs, initial labs (CBC, coagulation screen), and specific tests for bleeding disorders (vWD panel, platelet function tests) if indicated.

- Treatment & Management (Hematology Focus) ▾: Includes antifibrinolytics (tranexamic acid), hormonal therapies, and critically, specific management of identified bleeding disorders (e.g., DDAVP, factor concentrates), plus iron supplementation for anemia.

- Long-Term Complications ▾: Chiefly iron deficiency anemia, which can lead to severe fatigue, impaired quality of life, and in extreme cases, the need for recurrent blood transfusions.

*Click ▾ for more information

Introduction

Menorrhagia is defined as excessive or prolonged menstrual bleeding. This means menstrual periods that are unusually heavy, lasting longer than seven days, or both.

Menorrhagia is a significant health concern due to its profound impact on a person’s quality of life and potential health consequences. The most common complication is iron deficiency anemia, which can lead to symptoms like fatigue, shortness of breath, dizziness, and decreased cognitive function. It can also cause significant distress, anxiety, and limitations in daily activities due to the unpredictable and heavy bleeding. From a hematology perspective, its significance lies in the fact that it is frequently the presenting symptom of an underlying bleeding disorder, such as Von Willebrand Disease or platelet function disorders, which are crucial to diagnose and manage.

Menorrhagia is a common gynecological complaint, affecting a substantial portion of menstruating individuals. While exact figures vary, studies suggest that 10-30% of women of reproductive age experience menorrhagia. It is one of the most frequent reasons for gynecological consultations and can affect individuals across all age groups from adolescence to perimenopause.

Pathophysiology of Normal Menstruation

Normal menstruation is a highly coordinated physiological process involving the interplay of hormones, changes in the uterine lining (endometrium), and a delicate balance of coagulation and fibrinolysis to ensure controlled bleeding and subsequent repair.

Hormonal Regulation

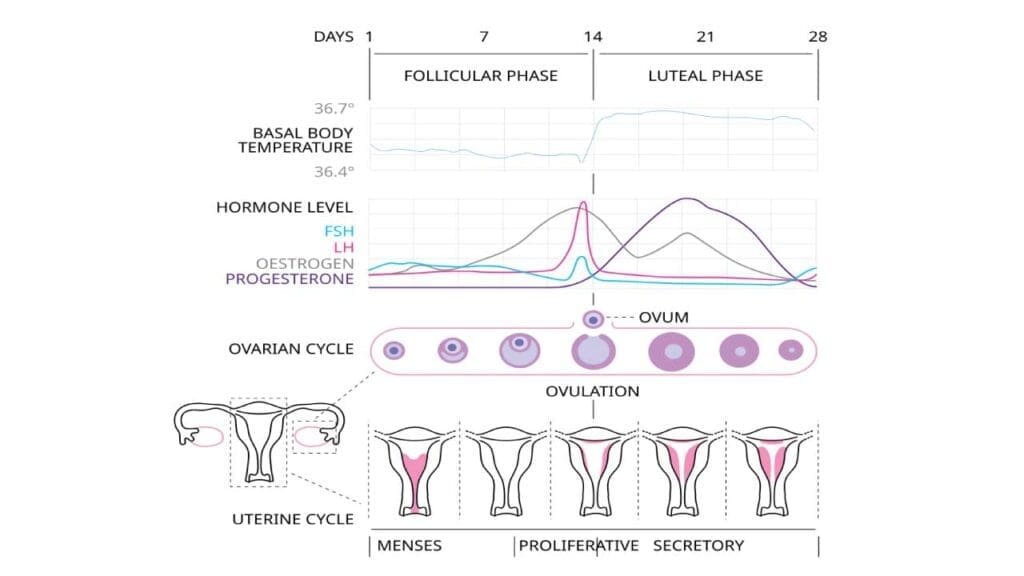

The menstrual cycle is primarily regulated by hormones produced by the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and ovaries.

- Hypothalamus: Secretes Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) in a pulsatile manner.

- Pituitary Gland: In response to GnRH, the anterior pituitary releases Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) and Luteinizing Hormone (LH). FSH stimulates the growth and development of ovarian follicles, which in turn produce estrogen. Luteinizing Hormone (LH) triggers ovulation (release of an egg) and promotes the formation of the corpus luteum from the ruptured follicle.

- Ovaries: Produce estrogen which is predominant in the first half of the cycle (follicular phase) and it stimulates the proliferation and thickening of the endometrial lining. The corpus luteum of the ovaries produce progesterone which is predominant in the second half of the cycle (luteal phase). It stabilizes the estrogen-primed endometrium, making it receptive for potential embryo implantation and promoting glandular secretion.

The cyclical rise and fall of these hormones orchestrate the entire menstrual process. If pregnancy does not occur, the corpus luteum degenerates, leading to a sharp drop in progesterone and estrogen levels. This hormonal withdrawal is the primary trigger for menstruation.

Endometrial Changes

The endometrium, the inner lining of the uterus, undergoes predictable changes throughout the menstrual cycle in response to ovarian hormones.

- Menstrual Phase (Days 1-5, approximately): With the decline in estrogen and progesterone, the functional layer of the endometrium (stratum functionalis) undergoes ischemic necrosis, vasoconstriction, and ultimately sheds, resulting in menstrual bleeding. This phase involves a controlled “inflammatory” response with local immune cell infiltration and enzymatic degradation of tissue.

- Proliferative Phase (Days 5-14, approximately): Under the influence of rising estrogen levels, the endometrium rapidly regenerates from the basal layer (stratum basalis) and thickens. Endometrial glands and stromal cells proliferate, and new blood vessels form (angiogenesis).

- Secretory Phase (Days 14-28, approximately): Following ovulation, progesterone from the corpus luteum dominates. This hormone causes the endometrium to become highly vascularized and secretory, preparing it for embryo implantation. Glands become tortuous and produce glycogen-rich secretions.

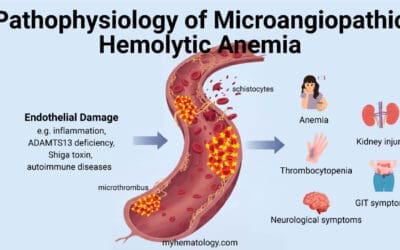

Coagulation and Fibrinolysis in Menstrual Blood Loss

The cessation of menstrual bleeding is a finely tuned process involving both systemic and local hemostatic mechanisms,

- Initial Hemostasis: As the endometrium sheds, blood vessels are exposed. Platelet aggregation and the activation of the coagulation cascade lead to the formation of fibrin clots, which are essential for controlling the initial blood loss. Local factors like tissue factor and thrombin play crucial roles.

- Localized Fibrinolysis: Uniquely, the uterine cavity possesses a highly active fibrinolytic system. High concentrations of plasminogen activators (like tissue plasminogen activator, tPA) are present in the endometrium and menstrual fluid. These activators convert plasminogen to plasmin, which then degrades fibrin clots. This localized fibrinolysis is critical to prevent excessive clotting within the uterine cavity, allowing shed tissue and blood to be expelled without causing uterine adhesions or obstruction.

Normal menstruation is a delicate balance between procoagulant factors that promote clotting to stop bleeding and profibrinolytic factors that ensure the menstrual blood remains fluid and can be shed. An imbalance in this system, either towards excessive bleeding (e.g., due to impaired clotting or enhanced fibrinolysis) or excessive clotting, can lead to menstrual disorders.

Causes of Menorrhagia

Uterine/Gynecological Causes

- Fibroids: Non-cancerous growths in the uterus.

- Adenomyosis: Endometrial tissue grows into the uterine muscle.

- Polyps: Growths in the uterine lining.

- Endometrial hyperplasia/carcinoma: Thickening or cancer of the uterine lining.

- IUD-related: Especially non-hormonal IUDs.

Systemic Causes with a Strong Hematological Link

Bleeding Disorders

- Von Willebrand Disease (vWD): The most common inherited bleeding disorder. It involves a deficiency or dysfunction of von Willebrand factor, a protein essential for platelet adhesion and factor VIII transport. This leads to impaired primary hemostasis and can cause significant menorrhagia, often the presenting symptom.

- Platelet Function Disorders: These disorders involve defects in platelet adhesion, aggregation, or secretion, even if the platelet count is normal. Examples include Glanzmann thrombasthenia, Bernard-Soulier syndrome, and acquired platelet dysfunction (e.g., due to medications like aspirin or NSAIDs).

- Coagulation Factor Deficiencies: Deficiencies in factors like Factor VII, XI, or XIII can, though less commonly than vWD, contribute to menorrhagia. Factor VIII deficiency (hemophilia A) and Factor IX deficiency (hemophilia B) are less likely to present primarily as menorrhagia but can exacerbate it.

- Inherited Fibrinolytic Disorders: Rare conditions where there is excessive breakdown of clots.

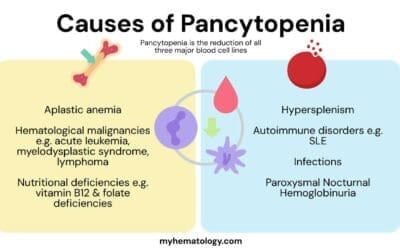

Acquired Coagulation Disorders

- Anticoagulant medication use (e.g., warfarin, direct oral anticoagulants): These medications intentionally interfere with the clotting cascade.

- Liver disease: The liver synthesizes many clotting factors.

- Renal failure: Can affect platelet function.

- Thrombocytopenia: Low platelet count due to conditions like immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura (TTP), or bone marrow disorders.

- Dysfibrinogenemia: Abnormal fibrinogen, a crucial clotting protein.

Thyroid Dysfunction (Hypothyroidism)

Can affect the menstrual cycle and sometimes lead to heavier bleeding.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) and other autoimmune conditions

These can lead to acquired coagulopathies or affect platelet function.

Approach to Diagnosing Menorrhagia

Diagnosing menorrhagia involves a systematic approach to confirm the diagnosis, quantify blood loss (if possible), assess the impact on the patient’s health (e.g., anemia), and, most importantly from a hematology perspective, identify the underlying cause, especially bleeding disorders.

History Taking

A detailed patient history is paramount for evaluating menorrhagia and can often provide critical clues towards an underlying cause, particularly a bleeding disorder.

Duration and Volume of Bleeding

- Length of periods: Are they consistently longer than 7 days?

- Frequency of pad/tampon changes: Requiring changes every hour or two for several consecutive hours is a strong indicator of menorrhagia.

- Presence of large blood clots: Passing clots larger than a quarter (or a 10 sen coin) is significant.

- “Flooding” or “gushing”: Episodes of sudden, heavy blood loss that soil clothes or bedding.

- Doubling up on sanitary protection: Using both pads and tampons simultaneously.

- Bleeding through clothes or bedding: An undeniable sign of excessive volume.

- Need to wake up at night to change protection.

Impact on Daily Activities

- Interference with work, school, or social activities: Do periods force the individual to miss these activities or significantly alter their routine?

- Avoidance of physical activities: Reluctance to exercise or participate in sports due to fear of leakage.

Associated Symptoms (Signs of Anemia)

- Fatigue and Tiredness: Often profound and disproportionate to activity.

- Shortness of breath (Dyspnea): Especially on exertion.

- Dizziness or Lightheadedness: Can be a sign of significant blood loss or severe anemia.

- Palpitations: Sensation of a racing or pounding heart.

- Weakness: General feeling of lack of strength.

- Pallor: Noticeable paleness of the skin and mucous membranes.

Personal History of Bleeding

- Nosebleeds (epistaxis): Frequent, prolonged, or difficult-to-stop nosebleeds, especially since childhood.

- Easy bruising: Bruises that are large, multiple, or appear with minimal trauma.

- Prolonged bleeding after minor cuts or dental procedures: Bleeding lasting for hours or days after tooth extractions or minor surgeries.

- Excessive bleeding after major surgeries (e.g., tonsillectomy, appendectomy):

- Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) in previous pregnancies.

- Bleeding into joints (hemarthroses) or muscles (hematomas): While less common with menorrhagia alone, these indicate more severe inherited coagulopathies.

- History of blood transfusions: Especially if for bleeding.

Family History of Bleeding Disorders

Any family members (parents, siblings, aunts/uncles, cousins) with a history of menorrhagia, easy bruising, nosebleeds, prolonged bleeding after surgery/dental work, or diagnosed bleeding disorders (e.g., von Willebrand Disease, hemophilia, platelet disorders). A positive family history significantly increases the suspicion for an inherited coagulopathy.

Medication History

- Anticoagulants: Warfarin, direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs like rivaroxaban, apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban).

- Antiplatelet agents: Aspirin, clopidogrel.

- NSAIDs (Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs): Can inhibit platelet function.

- Herbal supplements or over-the-counter medications: Some can affect coagulation.

Physical Examination

- General Assessment: Pallor (skin, conjunctivae, nail beds), vital signs (tachycardia in severe anemia).

- Signs of a Bleeding Disorder: Look for petechiae, purpura, ecchymoses, mucosal bleeding (gums, nose), or signs of previous significant bleeding (e.g., joint deformities from hemarthroses, though rare with menorrhagia alone).

- Gynecological Examination: A pelvic exam is essential to identify obvious uterine or cervical pathologies (fibroids, polyps, cervicitis, etc.).

Identifying the Underlying Cause

Once menorrhagia is suspected, the focus shifts to uncovering its etiology. In a hematology context, the priority is to rule out or diagnose a bleeding disorder.

Initial Screening Tests

Complete Blood Count (CBC) with Differential

- Hemoglobin (Hb) and Hematocrit (Hct): Essential to assess for anemia, which is a common consequence of chronic blood loss. The severity of anemia often correlates with the duration and heaviness of menorrhagia.

- Red Cell Indices (MCV, MCH, MCHC): Help characterize the type of anemia. A low MCV (microcytic) is typical of iron deficiency anemia due to chronic blood loss.

- Platelet Count: Crucial to identify thrombocytopenia (low platelet count), which can directly cause menorrhagia. A normal count does not rule out platelet dysfunction.

Coagulation Screen

These tests assess the extrinsic, intrinsic, and common pathways of coagulation.

- Prothrombin Time (PT) / International Normalized Ratio (INR): Primarily assesses the extrinsic and common pathways (Factors I, II, V, VII, X). Prolongation can indicate liver disease, vitamin K deficiency, or certain factor deficiencies (e.g., Factor VII).

- Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (aPTT): Assesses the intrinsic and common pathways (Factors I, II, V, VIII, IX, X, XI, XII). Prolongation can suggest deficiencies in these factors (e.g., hemophilia, severe von Willebrand disease), or presence of an anticoagulant.

- Thrombin Time (TT): Measures the time for fibrinogen to convert to fibrin, evaluating the final step of the common pathway. Prolongation can indicate dysfibrinogenemia or the presence of thrombin inhibitors (e.g., heparin).

- Fibrinogen Level: Measures the amount of fibrinogen, a critical protein for clot formation.

Specific Tests for Bleeding Disorders

If the initial history strongly suggests a bleeding disorder (e.g., positive personal or family history of bleeding symptoms beyond menorrhagia) or if initial screening tests are abnormal, more specialized hematological tests are warranted.

Von Willebrand Disease (vWD) Panel

This is often the first specific test considered if a bleeding disorder is suspected, especially given vWD’s prevalence in menorrhagia.

- Von Willebrand Factor Antigen (vWF:Ag): Measures the quantity of vWF protein.

- Von Willebrand Factor Ristocetin Cofactor Activity (vWF:RCo) or Collagen Binding Assay (vWF:CB): Measures the function of vWF in platelet adhesion. A discrepancy between vWF:Ag and vWF:RCo can indicate qualitative defects (Type 2 vWD).

- Factor VIII Activity: Since vWF protects Factor VIII from degradation, vWD often presents with reduced Factor VIII activity.

Platelet Function Tests

- Platelet Function Analyzer (PFA-100/200): A common screening test for primary hemostasis (platelet function and vWF activity). It measures the time for a platelet plug to form in a capillary. A prolonged closure time can indicate vWD or a platelet function disorder.

- Platelet Aggregation Studies: More specialized tests that assess how platelets clump together in response to various agonists (e.g., ADP, collagen, epinephrine, ristocetin). Abnormal aggregation patterns can diagnose specific inherited platelet disorders (e.g., Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia, Bernard-Soulier syndrome).

- Flow Cytometry for Platelet Surface Glycoproteins: Used to diagnose specific platelet disorders by identifying absence or deficiency of certain surface receptors (e.g., GPIIb/IIIa in Glanzmann’s, GPIb/IX/V in Bernard-Soulier).

Specific Coagulation Factor Assays

If PT or aPTT is prolonged, assays for specific factors (e.g., Factor XI, Factor XIII, Factor VII, Factor V, Factor X, Factor II) may be performed to pinpoint the exact deficiency.

Fibrinolysis Assays

If primary and secondary hemostasis tests are normal but suspicion for bleeding remains, tests like D-dimer, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), or alpha-2 antiplasmin levels may be considered, though inherited fibrinolytic disorders are rare causes of menorrhagia.

Other Relevant Investigations

- Thyroid Function Tests (TSH, Free T4): Hypothyroidism can cause menorrhagia and should be ruled out.

- Ferritin: Measures the body’s iron stores. Crucial for diagnosing iron deficiency anemia, which is a common consequence of chronic menorrhagia, even before Hb drops significantly.

- Liver and Renal Function Tests: To rule out systemic diseases affecting coagulation.

Imaging Studies (Primarily Gynecological Assessment)

While not direct hematological investigations, imaging is crucial for identifying structural uterine causes.

- Transvaginal Ultrasound (TVS): The primary imaging modality to detect fibroids, adenomyosis, polyps, or endometrial abnormalities.

- Saline Infusion Sonohysterography (SIS) / Hysteroscopy: May be used if ultrasound findings are inconclusive or to better visualize endometrial lesions.

Treatment and Management in Relation to Hematology

The treatment and management of menorrhagia in relation to hematology focuses on three key areas: managing the acute bleeding, correcting underlying hematological defects, and addressing associated complications like iron deficiency anemia.

General Management of Menorrhagia

While often initiated by gynecologists, certain medications directly impact hematological processes:

- Tranexamic acid (antifibrinolytic): This medication inhibits the breakdown of fibrin clots by plasmin, thereby promoting clot stability at the endometrial surface and reducing blood loss. Its mechanism directly relates to the fibrinolytic system, a crucial part of hemostasis.

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): These can reduce prostaglandin synthesis, which lessens bleeding and pain. However, caution is advised as prolonged or high-dose NSAID use can inhibit platelet function, potentially worsening bleeding in individuals with underlying hemostatic defects.

- Hormonal therapies (e.g., combined oral contraceptives, progestins): These stabilize the endometrial lining, reducing shedding and blood loss. While not directly hematological, they are a common initial treatment.

Specific Hematological Management

This is paramount when an underlying bleeding disorder is identified.

Management of Bleeding Disorders

- Von Willebrand Disease (vWD)

- Desmopressin (DDAVP): This synthetic analogue of vasopressin stimulates the release of endogenous von Willebrand factor (vWF) and Factor VIII from endothelial cells, effectively improving primary hemostasis. It’s often the first-line treatment for Type 1 vWD and some Type 2 variants.

- vWF/Factor VIII Concentrates: For severe vWD, or types unresponsive to DDAVP, replacement therapy with plasma-derived or recombinant vWF/Factor VIII concentrates is necessary to provide the missing clotting factors.

- Platelet Function Disorders

- Desmopressin (DDAVP): Can also be effective in some platelet function disorders by promoting platelet adhesion.

- Platelet Transfusions: Reserved for severe acute bleeding or in preparation for surgery when other measures fail.

- Antifibrinolytics (Tranexamic Acid): Often used to stabilize clots and reduce bleeding.

- Factor Deficiencies: Specific factor replacement therapy (e.g., Factor XI concentrate) if a rare coagulation factor deficiency is identified.

- Thrombocytopenia: Treatment is aimed at the underlying cause of low platelet count (e.g., corticosteroids for ITP, specific therapies for bone marrow disorders).

- Anticoagulant Reversal/Adjustment: If menorrhagia is caused or exacerbated by anticoagulant medications, adjustment of dosage or temporary discontinuation/reversal strategies (e.g., Vitamin K for warfarin, specific antidotes for DOACs) are managed by the hematologist.

Management of Anemia

- Iron Supplementation: The cornerstone of managing iron deficiency anemia resulting from chronic blood loss. Oral iron is typically first-line, but intravenous iron may be necessary for severe anemia, poor oral tolerance, or malabsorption.

- Blood Transfusions: Reserved for acute, severe anemia causing hemodynamic instability or severe symptoms, or when immediate correction is required.

- Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agents (ESAs): Less commonly used for menorrhagia-induced anemia but can be considered in specific refractory cases.

Long-Term Complications of Undiagnosed/Untreated Menorrhagia

Iron Deficiency Anemia (IDA)

- Symptoms and Impact on Quality of Life: Chronic excessive blood loss depletes the body’s iron stores, leading to iron deficiency. This can manifest as severe and persistent fatigue, weakness, pallor, shortness of breath on exertion, dizziness, headaches, cold intolerance, restless legs syndrome, and even cognitive impairment. This significantly diminishes the patient’s overall quality of life, productivity, and ability to perform daily activities.

- Progression to Severe Anemia: If menorrhagia remains undiagnosed or untreated, the ongoing blood loss can lead to progressively worsening anemia, sometimes reaching critically low hemoglobin levels requiring urgent intervention.

- Impact on Bone Marrow: In cases of chronic and severe iron deficiency anemia, the bone marrow, while attempting to compensate by increasing red blood cell production (erythropoiesis), may become exhausted or less efficient if iron substrate is continually lacking. This can lead to ineffective erythropoiesis, making the anemia more difficult to resolve.

- Potential for Transfusion Dependency: In severe, chronic, or refractory cases of menorrhagia-induced anemia, patients may become recurrently symptomatic with very low hemoglobin levels, necessitating repeated blood transfusions. This can expose patients to transfusion-related risks (e.g., allergic reactions, febrile non-hemolytic transfusion reactions, alloimmunization, iron overload in very long-term scenarios), and represents a significant burden on the patient and healthcare system.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Can menorrhagia be life threatening?

While menorrhagia is often a chronic condition that significantly impacts quality of life, it can indeed be life-threatening in certain acute or severe circumstances, primarily due to excessive blood loss leading to severe anemia or hypovolemic shock.

Therefore, while not always an immediate emergency, the potential for acute, profound blood loss and the presence of serious underlying causes mean that menorrhagia should always be thoroughly evaluated and managed to prevent potentially fatal outcomes.

How many pads per day is normal?

There isn’t a single “normal” number of pads per day, as it can vary widely depending on the individual, the day of their period, and the type/absorbency of the pad used. However, general guidelines suggest that most individuals typically use 3 to 6 regular-sized pads or tampons per day during their period, with the heaviest flow usually occurring on the first one or two days.

If you find yourself needing to change a pad or tampon every one to two hours for several consecutive hours, needing to double up on sanitary products to prevent leaks, or changing pads overnight, these are strong indicators of a heavier-than-normal flow (menorrhagia) and should prompt a discussion with a healthcare provider.

Is menorrhagia caused by stress?

Yes, stress can contribute to or exacerbate menorrhagia, though it’s typically not the sole or primary cause, especially if there’s an underlying gynecological or hematological condition.

The connection lies in how chronic or significant stress impacts the body’s hormonal balance, particularly the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which interacts with the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis that regulates the menstrual cycle.

Elevated levels of stress hormones like cortisol can disrupt the delicate balance of reproductive hormones (estrogen and progesterone), potentially leading to anovulation (lack of ovulation) or irregular thickening and shedding of the endometrial lining, which can result in heavier or more irregular bleeding. While research findings on the exact link between stress and menorrhagia can sometimes be mixed, many studies and clinical observations suggest that high levels of psychological stress can indeed influence menstrual flow, potentially making periods heavier for some individuals. Therefore, while other causes should always be investigated, stress management is a relevant consideration in the holistic management of menorrhagia.

Can I get pregnant with menorrhagia?

Yes, it is possible to get pregnant with menorrhagia, but the presence of heavy or prolonged bleeding can certainly impact fertility and increase the risk of complications during pregnancy.

Menorrhagia itself is a symptom, and whether it affects your ability to conceive largely depends on its underlying cause. If the menorrhagia is due to hormonal imbalances that disrupt ovulation (e.g., anovulatory cycles), or conditions like Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), then fertility can be directly impacted.

Similarly, structural abnormalities such as uterine fibroids (especially those distorting the uterine cavity), endometrial polyps, or endometriosis can interfere with implantation or increase the risk of miscarriage, thus making it harder to sustain a pregnancy.

While some causes of menorrhagia, like certain bleeding disorders, might not directly prevent conception, they can increase the risk of bleeding complications during pregnancy and childbirth, such as postpartum hemorrhage. Therefore, if you are experiencing menorrhagia and trying to conceive, it is highly recommended to seek medical evaluation to identify and address the underlying cause, as treating it can significantly improve your chances of a successful pregnancy and reduce potential risks.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Goldberg S, Hoffman J. Clinical Hematology Made Ridiculously Simple, 1st Edition: An Incredibly Easy Way to Learn for Medical, Nursing, PA Students, and General Practitioners (MedMaster Medical Books). 2021.

- Garrison C. The Iron Disorders Institute Guide to Anemia: Understanding the Causes, Symptoms, and Healing of Iron Deficiency and Other Anemias (Cumberland House). 2009.

- Mansour, D., Hofmann, A., & Gemzell-Danielsson, K. (2021). A Review of Clinical Guidelines on the Management of Iron Deficiency and Iron-Deficiency Anemia in Women with Heavy Menstrual Bleeding. Advances in therapy, 38(1), 201–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-020-01564-y

- Borzutzky C, Jaffray J. Diagnosis and Management of Heavy Menstrual Bleeding and Bleeding Disorders in Adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 Feb 1;174(2):186-194. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.5040. PMID: 31886837.

- Lebduska E, Beshear D, Spataro BM. Abnormal Uterine Bleeding. Med Clin North Am. 2023 Mar;107(2):235-246. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2022.10.014. Epub 2022 Dec 26. PMID: 36759094.