TL;DR

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a slow progressing cancer due to overgrowth and accumulation of small incompetent mature-looking B-lymphocytes in the blood, bone marrow and lymphoid tissues. Small lymphocytic leukemia is a different clinical manifestation of this disorder.

Incidence:

- Peak at > 65 years old

- Common in Western societies

- Male:female ratio is 2.8:1

- Discrete, non-tender symmetrical enlargement of the cervical, axillary or inguinal lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy)

- Splenomegaly

- Anemia

- Immunosuppression due to hypogammaglobulinemia

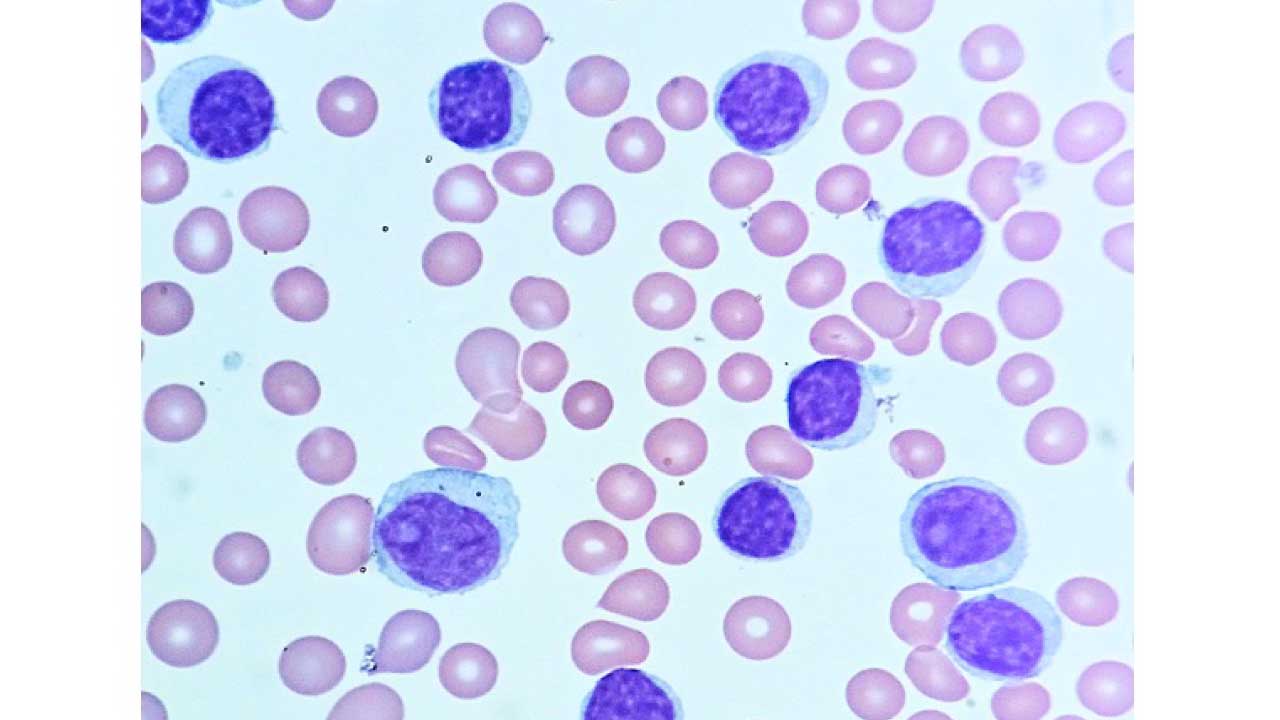

- PBF: Lymphocytosis with smudge cells. Normochromic normocytic anemia in bone marrow infiltration.

- Immunophenotyping: CD5+, CD19+, CD20+, CD23+ and surface immunoglobulin+

- FISH: Trisomy 12 (intermediate prognosis) , del17p (least favorable prognosis), del11q (least favorable prognosis), del13q (best prognosis)

- ↓ serum immunoglobulins

| Rai stage | Characteristics | |||

| Rai 0 | Lymphocytosis only >15 x 109/L | |||

| Rai I | Lymphocytosis + lymphadenopathy | |||

| Rai II | Lymphocytosis + hepato-/splenomegaly ± lymphadenopathy | |||

| Rai III | Lymphocytosis + anemia (Hb < 11g/dL) ± lymphadenopathy ± organomegaly | |||

| Rai IV | Lymphocytosis + platelets < 100 x 109/L ± lymphadenopathy ± organomegaly | |||

| Binet stage | Lymphadenopathy/Organomegaly | Hemoglobin (g/dL) | Platelets (x 109/L) | |

| Binet A | ≤ 2 areas involved | > 10 | > 100 | |

| Binet B | ≥ 3 areas involved | ≥ 10 | ≥ 100 | |

| Binet C | Not considered | < 10 | < 100 | |

*Lymphadenopathy (> 1cm) /Organomegaly areas:

- Head and neck (uni- or bilateral)

- Axillar (uni- or bilateral)

- Inguinal (uni- or bilateral)

- Splenomegaly

- Hepatomegaly

- No treatment for Rai 0 – II stage and Binet A – B stage

- Targeted therapy e.g. BTK inhibitors, BCL-2 inhibitors

- Chemoimmunotherapy e.g. purine analogs/ alkylating agents + anti-B cell monoclonal antibodies

*Click ▾ for more information

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a type of cancer that begins in the bone marrow. It is characterized clinically by the overproduction and accumulation of small mature-looking but functionally incompetent B-lymphocytes in blood, bone marrow and lymphoid tissues.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) cells are abnormal and grow out of control in the bone marrow. Over time, the accumulation of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) cells can crowd out the healthy white blood cells, making it difficult for the body to fight infection. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) can also spread to other parts of the body, such as the lymph nodes, liver, and spleen.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a slow-growing cancer, and many people with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) do not need treatment right away. However, when treatment is needed, there are a number of options available, including chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy.

Most patients present with leukemia whereas a small minority present with small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL). In earlier classifications of lymphoid malignancies, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and SLL were considered to be separate entities but they are now accepted to be different clinical manifestations of the same disease.

Epidemiology

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) holds the distinction of being the most common leukemia in adults in Western countries.

- Age: CLL is classically a disease of the elderly, with the median age at diagnosis hovering around 70 years. It is rarely seen in individuals under 40. This strong age correlation suggests that accumulated genetic damage and immune dysregulation over time contribute significantly to its pathogenesis.

- Sex: There is a notable sex predilection, with men being affected approximately twice as often as women (M:F ratio ≈2:1).

- Geography/Genetics: Incidence rates vary significantly globally. They are highest in North America and Europe, and considerably lower in East Asian populations. This suggests that both genetic factors and undefined environmental factors may play a role in susceptibility.

Cellular Origin

CLL arises from a clonal expansion of B-lymphocytes, but these cells possess a very specific and unusual immunophenotype that differentiates them from other lymphomas and leukemias.

The CLL cell is considered a mature, but functionally incompetent, B-lymphocyte. It resides in an arrested state of development, resembling either a memory B-cell or a B-cell in the mantle zone of a lymphoid follicle.

For diagnostic purposes via flow cytometry, the classic CLL immunophenotype is a pattern characterized by the co-expression of markers from two different lineages:

- B-cell Markers: CD19, CD20 (usually weakly expressed), CD23 (strongly expressed).

- The T-cell Marker (Aberrant Co-expression): CD5. The co-expression of CD5 and CD23 is a hallmark of CLL and helps distinguish it from other B-cell malignancies like Follicular Lymphoma (CD5-negative) or Mantle Cell Lymphoma (CD23-negative).

- Surface Immunoglobulin (sIg): Typically expressed at a very low level and is often restricted to a single light chain (kappa or lambda), confirming clonality.

Pathophysiology of CLL

Unlike highly proliferative cancers, chronic lymphocytic leukemia is primarily a disease of accumulation rather than uncontrolled proliferation. The malignant cells are exceptionally long-lived due to mechanisms that prevent their natural programmed cell death (apoptosis).

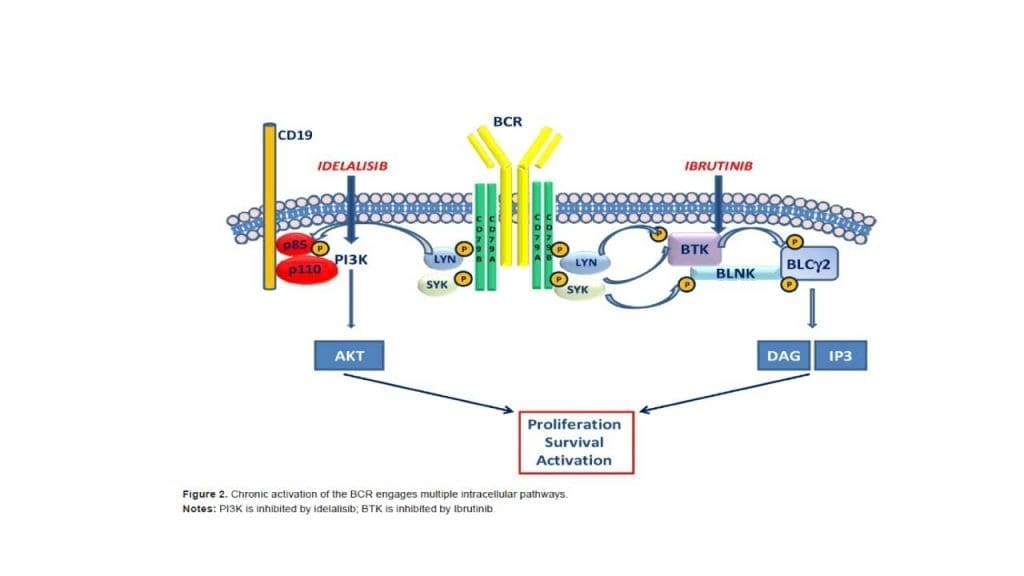

The Central Role of the B-Cell Receptor (BCR)

The B-cell receptor is the master regulator of the chronic lymphocytic leukemia cell’s life. Signaling through the BCR drives cell survival and proliferation. The primary issue in CLL is the failure of malignant B-cells to die, leading to their slow but steady accumulation in the blood, bone marrow, and lymph nodes.

CLL B-cells express a unique type of BCR that often recognizes self-antigens (autoimmunity). This continuous, low-level signaling through the BCR drives the malignant process. Activation of the BCR initiates a cascade of intracellular signals involving key enzymes, most notably Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase (BTK). When the BCR is stimulated, BTK is activated. BTK then drives multiple pathways that promote cell survival and movement. This dependency on BTK makes it the ideal therapeutic target for inhibitors like Ibrutinib.

Apoptosis Resistance and BCL−2 Overexpression

To survive indefinitely, chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells must deactivate the cellular suicide pathway (apoptosis). Malignant CLL cells are “addicted” to anti-apoptotic proteins, particularly BCL−2 (B-cell lymphoma 2). BCL−2 normally prevents the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria, which is necessary to trigger the cell’s death cascade. By overexpressing BCL−2, CLL cells essentially keep the mitochondrial gate firmly shut, preventing them from dying.

The Microenvironmental Niche and Proliferative Centers

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells are largely dependent on external cues for survival; they are often called “socially dependent” tumors. They cannot survive alone in the peripheral blood. The CLL cells migrate to specialized sanctuary sites—the proliferative centers (also called pseudo-follicles) found primarily within the lymph nodes, bone marrow, and spleen.

In these niches, the CLL B-cells receive critical survival signals from supporting cells:

- Nurse-like cells (NLCs): Macrophage-like cells that provide cytokines.

- T-cells: Helper T-cells provide necessary survival factors.

- Stromal cells: Cells that make up the tissue scaffolding.

The interaction between the chronic lymphocytic leukemia cell and these stromal/immune cells involves chemokines (like CXCL12 and CXCL13) and adhesion molecules, which again feed back to activate the BTK pathway. This allows the CLL cell to proliferate, replenish the circulating pool, and resist drug therapy.

Causes and Risk Factors of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

The exact cause of chronic lymphocytic leukemia remains unknown, but the disease arises from a complex interplay of genetic susceptibility, advanced age, and potentially environmental exposures.

Genetic Predisposition and Familial Risk

Genetic factors play a strong role in chronic lymphocytic leukemia, which often clusters in families.

- Familial CLL: Having a first-degree relative (parent, sibling, or child) with CLL increases an individual’s risk by approximately two to seven times. Familial clusters are also noted among other B-cell malignancies, suggesting a shared inherited susceptibility to B-cell dysfunction.

- Precursor State: Monoclonal B-cell Lymphocytosis (MBL): MBL is a condition where a small clone of B-cells with the CLL immunophenotype (CD5+,CD23+) is present in the blood, but the cell count is below the diagnostic threshold for CLL (i.e., less than 5×109/L). MBL is highly common in the general elderly population (found in up to 10-15% of healthy adults). The vast majority of MBL cases remain stable. However, MBL is considered the obligate precursor to CLL. Individuals with MBL progress to frank CLL at a slow, stable rate of about 1–2% per year.

Demographic Factors: Age, Sex, and Race

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia is characterized by a distinct demographic profile that serves as a primary risk indicator.

- Age: The risk for CLL rises dramatically with age. The median age at diagnosis is approximately 70 years, and it is extremely rare in people under 40.

- Sex: There is a consistent male predominance, with men being affected nearly twice as often as women (M:F ratio ≈2:1).

- Race/Ethnicity: The incidence is highest among individuals of European descent (Caucasians) and significantly lower in Asian populations, suggesting differences in genetic backgrounds or environmental exposures influence global risk.

Environmental and Occupational Factors

While less conclusive than genetic or age-related factors, certain environmental exposures have been investigated.

- Chemical Exposure (Pesticides/Herbicides): The most consistent environmental association identified is chronic, high-level occupational exposure to certain pesticides and herbicides. However, the specific chemical compounds and the mechanism of action remain subjects of ongoing research and debate.

- Ionizing Radiation: Unlike acute leukemias, there is no strong, confirmed link between exposure to ionizing radiation (e.g., from atomic bombs or occupational hazards) and an increased risk of developing CLL.

- Infectious Agents: There is currently no definitive evidence establishing a causal role for any common viral or bacterial infection in the development of CLL (in contrast to some other lymphomas, like endemic Burkitt’s lymphoma and Epstein-Barr virus).

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) Symptoms

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia is often called the “indolent” leukemia because of its slow progression and frequently silent presentation. Understanding the symptoms is key to determining when treatment is necessary.

Asymptomatic and Incidental Diagnosis (The Majority)

The most common presentation of CLL is no presentation at all.

Approximately two-thirds of patients are diagnosed incidentally. This usually occurs during a routine check-up when a Complete Blood Count (CBC) is ordered for an unrelated reason (e.g., pre-operative screening, annual physical).

The CBC reveals an unexpected, persistent, and significant absolute lymphocytosis (elevated lymphocyte count), which triggers further investigation via flow cytometry.

Constitutional (“B”) Symptoms (Indications for Treatment)

The presence of constitutional symptoms usually signifies active, advanced disease and is often a criterion for initiating therapy (“B” refers to the system used in lymphoma and leukemia staging).

These symptoms are non-specific but suggest high disease burden and hypermetabolic state:

| Symptom | Description |

|---|---|

| Unexplained Fever | Fevers (often low-grade) that are not attributable to a documented infection. |

| Drenching Night Sweats | Soaking sweats requiring a change of clothes or bedding, most commonly occurring at night. |

| Weight Loss | Unintentional loss of more than 10% of body weight within the previous 6 months. |

Physical Signs of Lymphoid Accumulation

As the malignant B-cells accumulate in lymphoid organs, physical examination may reveal the following:

- Generalized, Non-Tender Lymphadenopathy: This is the most frequent physical finding. The lymph nodes are typically discrete, firm, and non-tender. While they can occur anywhere, the cervical, supraclavicular, axillary, and inguinal nodes are most commonly affected. The presence of bulky lymphadenopathy (nodes ≥10 cm) is sometimes associated with a higher-risk cytogenetic profile, such as del(11q).

- Splenomegaly: Enlargement of the spleen is common, resulting from the infiltration of CLL cells. It can range from mild enlargement to massive splenomegaly.

- Hepatomegaly: Enlargement of the liver is less common than splenomegaly but may also be present due to infiltration.

Complications of Cytopenia (Bone Marrow Failure)

In advanced disease, the bone marrow becomes so heavily infiltrated with malignant B-cells that it begins to fail, suppressing the production of normal blood components (hematopoiesis).

- Anemia (Low Red Blood Cells): Leads to symptoms of fatigue, pallor, shortness of breath, and reduced exercise tolerance.

- Thrombocytopenia (Low Platelets): Leads to easy bruising, petechiae (pinpoint spots under the skin), and mucosal bleeding (e.g., nosebleeds).

- Neutropenia (Low Neutrophils): Although less common than the others, it predisposes the patient to serious and recurrent infections.

Laboratory Investigations & Diagnosis for CLL

Laboratory investigations are used to diagnose chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), monitor the progression of the disease, and assess the response to treatment. Some of the most common laboratory investigations used for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) include:

- Complete blood count (CBC) with differential: A CBC measures the number of different types of blood cells in the blood, including red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets. A CBC can show anemia, thrombocytopenia, and lymphocytosis (an increased number of lymphocytes) in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Normocytic normochromic anemia is present in later stages as a result of marrow infiltration or hypersplenism.

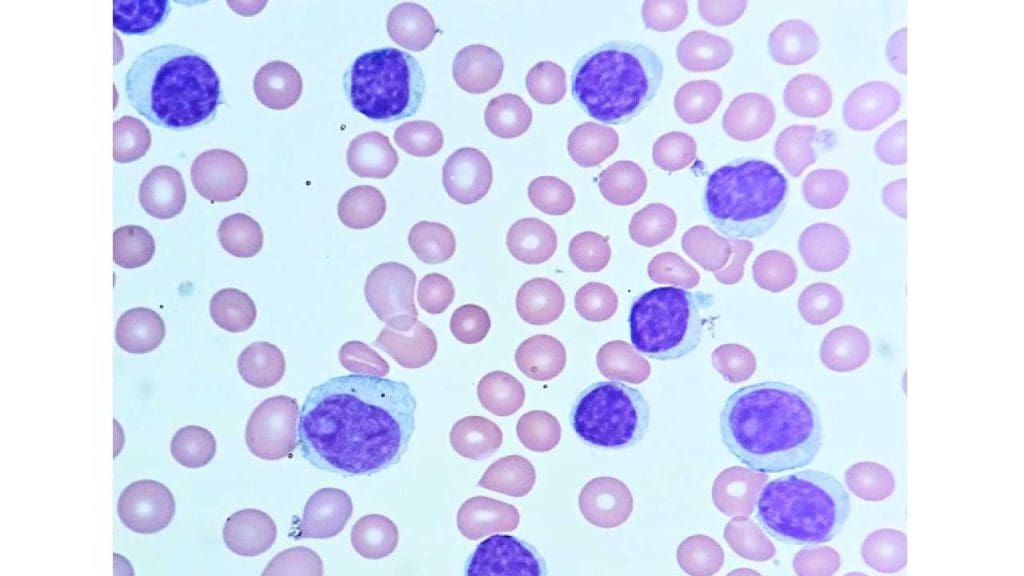

- Peripheral blood smear: A peripheral blood smear is a test that examines the different types of blood cells in a sample of blood under a microscope. A peripheral blood smear show lymphocytosis with smudge or smear cells.

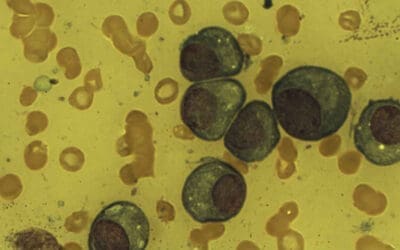

- Bone marrow biopsy: A bone marrow biopsy is a procedure in which a small sample of bone marrow is removed and examined under a microscope. A bone marrow biopsy can show the presence of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) cells and other abnormalities.

- Flow cytometry: Flow cytometry is a test that uses lasers to examine the characteristics of individual cells. Flow cytometry can be used to identify chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) cells and to distinguish them from other types of white blood cells. In chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), cells co‐express the surface antigen CD5 with the B‐cell antigens CD19, CD20, and CD23. The levels of surface immunoglobulin, CD20, and CD79b are characteristically low compared to those found on normal B cells. Each clone of leukemia cells is restricted to expression of either kappa or lambda immunoglobulin light chains. It should be noted that the expression of CD5 can also be observed in other lymphoid malignancies, such as mantle cell lymphoma. A recent, large harmonization effort has confirmed that a panel of CD19, CD5, CD20, CD23, kappa and lambda is usually sufficient to establish the diagnosis. In borderline cases, markers such as CD43, CD79b, CD81, CD200, CD10, or ROR1 may help to refine the diagnosis.

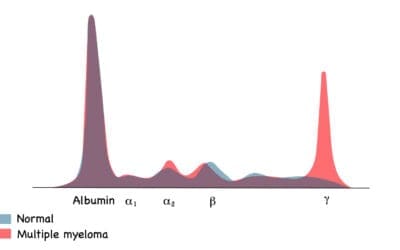

- Immunoglobulin studies: Immunoglobulin studies measure the levels of different types of immunoglobulins (antibodies) in the blood. There are reduced concentrations of serum immunoglobulins.

- Genetic testing: Genetic testing can be used to identify genetic mutations that are associated with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Genetic testing can be helpful for diagnosing chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and for predicting the prognosis of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

In addition to the laboratory investigations listed above, other laboratory tests may be used to monitor the progression of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and to assess the response to treatment. These tests may include:

- Serum beta-2 microglobulin (B2M): B2M is a protein that is released into the blood by chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) cells and other types of cells. Elevated levels of B2M are associated with a more aggressive form of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

- Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH): LDH is an enzyme that is released into the blood when cells are damaged. Elevated levels of LDH are associated with a more aggressive form of CLL.

- Imaging tests: Imaging tests, such as X-rays, computed tomography (CT) scans, and positron emission tomography (PET) scans, may be used to look for enlarged lymph nodes and other signs of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) Staging

Two widely accepted clinical staging systems co‐exist, named after the first authors of the original publications, Rai and Binet. Both systems describe three major prognostic groups with discrete clinical outcomes.

The Binet Staging System

The Binet staging system is based on two factors: the number of involved lymph node areas as defined by the presence of enlarged lymph nodes of greater than 1 cm in diameter or organomegaly and the presence of anemia or thrombocytopenia.

The Binet staging system has three stages:

- Stage A: Fewer than 3 lymph node areas are involved and there is no anemia or thrombocytopenia.

- Stage B: 3 or more lymph node areas are involved and there is no anemia or thrombocytopenia.

- Stage C: There is anemia or thrombocytopenia, regardless of the number of involved lymph node areas

The areas of involvement considered or lymph node regions are

- Head and neck, including the Waldeyer ring (this counts as one area, even if more than one group of nodes is enlarged)

- Axillae (involvement of both axillae counts as one area)

- Groins, including superficial femoral (involvement of both groins counts as one area)

- Palpable spleen

- Palpable liver (clinically enlarged)

The Binet staging system is important for determining the prognosis of patients with CLL and for guiding treatment decisions. Patients with early-stage CLL (Binet stage A) have a better prognosis than patients with advanced-stage CLL (Binet stage C).

The Modified Rai Staging System

The Rai staging system is based on three factors: the number of lymphocytes in the blood, the presence of enlarged lymph nodes, and the presence of anemia or thrombocytopenia.

The modified Rai staging system defines:

- Low‐risk disease: Patients who have lymphocytosis with leukemia cells in the blood and/or marrow (lymphoid cells >30%) (former Rai stage 0).

- Intermediate Risk: Patients with lymphocytosis, enlarged nodes in any site, and splenomegaly and/or hepatomegaly (lymph nodes being palpable or not) (formerly considered Rai stage I or stage II).

- High‐risk disease: Patients with disease‐related anemia (as defined by a hemoglobin [Hb] level less than 11 g/dL) (formerly stage III) or thrombocytopenia (as defined by a platelet count of less than 100 × 109/L) (formerly stage IV).

The Rai staging system is important for determining the prognosis of patients with CLL and for guiding treatment decisions. Patients with early-stage CLL (Rai stage 0 or I) have a better prognosis than patients with advanced-stage CLL (Rai stage III or IV).

Essential Prognostic and Predictive Markers (Molecular Risk Stratification)

These markers define the inherent aggressiveness of the cancer and are REQUIRED before starting first-line therapy, as they dictate the choice between targeted agents and chemotherapy.

Immunoglobulin Heavy Chain Variable Gene (IgHV) Mutation Status

This is determined by sequencing the IgHV gene and comparing it to the germline sequence.

| Status | Mutation Level | Prognosis | Treatment Preference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unmutated (IgHV-UM) | Identity ≥98% to germline | Worse (aggressive disease, higher proliferation) | Targeted Therapy (BTK/BCL-2 inhibitors) |

| Mutated (IgHV-M) | Identity <98% to germline | Better (indolent disease) | Can consider Chemoimmunotherapy (FCR) or Targeted Therapy |

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) and TP53 Status

FISH testing is used to detect common chromosomal deletions/abnormalities, which are organized into four major risk categories.

| Abnormality | Prognostic Risk | Clinical Feature | Therapeutic Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| del(17p) and/or TP53 Mutation | Highest Risk | Rapid progression, Chemoresistance | Requires Targeted Therapy; cannot use Chemoimmunotherapy. |

| del(11q) | High Risk | Associated with bulky lymphadenopathy. | Responds better to targeted therapy than Chemoimmunotherapy. |

| trisomy12 | Intermediate Risk | Atypical CLL morphology. | Intermediate prognosis. |

| del(13q) | Favorable Risk | Most common abnormality (approx. 50%). | Associated with the best prognosis. |

Clinical Takeaway: Modern practice always performs IgHV and FISH/TP53 testing. A patient with symptomatic disease and a high-risk marker (del(17p) or IgHV-UM) will be started directly on modern targeted agents (like BTK or BCL−2 inhibitors), bypassing older chemotherapy regimens.

Differential Diagnosis of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL)

When a patient presents with persistent absolute lymphocytosis, the differential diagnosis is extensive. It is the specific combination of morphology, immunophenotype, and clinical course that establishes the CLL diagnosis.

Other Chronic B-Cell Lymphoproliferative Disorders

These conditions often involve the accumulation of mature-appearing B-cells and are the most critical entities to distinguish from CLL, requiring flow cytometry and sometimes biopsy.

| Condition | CLL Distinguishing Features | Immunophenotype Key Differences |

|---|---|---|

| Monoclonal B-cell Lymphocytosis (MBL) | Precursor State: Clinically identical to CLL but with a lymphocyte count <5×109/L (i.e., below the diagnostic threshold). Asymptomatic and usually requires no follow-up. | CD5+/CD23+, identical to CLL. |

| Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL) | Aggressive: Often presents with bulky disease and rapidly progressive course. Requires urgent treatment. | CD5+, but CD23− (negative). |

| Follicular Lymphoma (Leukemic Phase) | Usually presents with nodal disease; leukemic involvement is less common. | CD5− (negative). |

| Splenic Marginal Zone Lymphoma (SMZL) | Presents classically with massive splenomegaly but minimal or absent lymphadenopathy. Cells often have villous projections. | CD5−/CD23−. |

| Hairy Cell Leukemia (HCL) | Pancytopenia and massive splenomegaly are common. Cells have characteristic “hairy” cytoplasmic projections. | CD5−, but shows strong expression of CD103, CD25, and CD123. |

Reactive (Non-Malignant) Lymphocytosis

This category includes benign conditions that cause a temporary or persistent increase in lymphocytes, typically in response to an infection or inflammation.

- Viral Infections (Acute):

- Infectious Mononucleosis (EBV): Characterized by lymphocytosis driven by atypical, activated T-cells (not B-cells) and heterophile antibodies (Monospot test). It is acute, not chronic.

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV), HIV: Can cause transient or persistent lymphocytosis.

- Pertussis (Whooping Cough): The causative bacterium releases factors that prevent lymphocytes from returning to the lymphoid organs, causing a marked, but non-malignant, lymphocytosis.

- Chronic Inflammation: Certain autoimmune conditions or chronic infections can cause a persistent polyclonal lymphocytosis.

In reactive conditions, the lymphocytosis is polyclonal (B-cells express both kappa and lambda light chains, or the T-cells are activated). In CLL, the lymphocytosis is strictly monoclonal, meaning all malignant B-cells are genetically identical and express only one type of light chain (kappa or lambda).

Atypical CLL Presentation

Sometimes, CLL presents differently, making the initial diagnosis confusing:

- Prolymphocytic Transformation: CLL can progress to CLL/Prolymphocytic Leukemia (PLL), where the circulating cells are larger and more aggressive. This usually signifies a poor prognosis.

- Richter’s Transformation: As mentioned previously, the transformation of CLL into a high-grade lymphoma (most commonly DLBCL). This is suggested by the rapid, painful enlargement of a lymph node or the sudden onset of severe B symptoms. This requires a diagnostic biopsy of the rapidly growing node.

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) Treatment

The management of chronic lymphocytic leukemia has undergone a revolution, shifting from non-specific chemotherapy to highly effective, oral targeted agents. The fundamental principle is that CLL is not always treated immediately.

Watchful Waiting (Active Surveillance)

The initial, and often only, management for many patients with CLL is Watchful Waiting. Studies have shown that treating asymptomatic, early-stage CLL with initial therapy does not improve overall survival but only exposes the patient to unnecessary drug toxicity. Watchful Waiting is employed for patients who are:

- Asymptomatic (lack B symptoms).

- In the low-risk stages (Rai Stage 0, Binet Stage A).

- Have stable, low disease burden.

Patients on Watchful Waiting are monitored closely (e.g., every 3-6 months) with a physical exam and CBC.

Indications for Treatment (“When to Treat”)

Treatment is only initiated when the patient meets specific criteria that indicate active, progressive, or symptomatic disease. These criteria include:

- Constitutional Symptoms: Presence of “B” symptoms (unexplained fever, drenching night sweats, weight loss ≥10% in 6 months).

- Progressive Cytopenias: Anemia (Hb<11 g/dL) or severe thrombocytopenia (Platelets <100×109/L) that is progressive and clearly due to bone marrow failure. Autoimmune cytopenias (AIHA, ITP) are treated separately, often with steroids.

- Bulky/Progressive Lymphadenopathy: Rapidly enlarging or massive lymph nodes (≥10 cm) or splenomegaly.

- Rapidly Increasing Lymphocytosis: A doubling of the lymphocyte count in less than 6 months.

First-Line Treatment: The Targeted Therapy Era

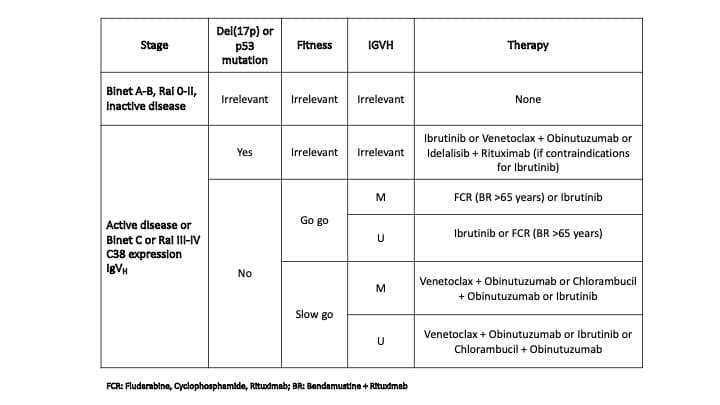

The choice of first-line therapy is driven almost entirely by the patient’s fitness and their molecular risk profile (IgHV status and TP53/FISH).

- BTK Inhibitors (e.g., Ibrutinib, Acalabrutinib): These are oral, small-molecule drugs that irreversibly (or reversibly) block the Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase (BTK) enzyme. By blocking BTK, they prevent the survival signals that drive the CLL cells from the lymph node sanctuary. They are highly effective in high-risk patients, particularly those with del(17p) or TP53 mutations, where chemotherapy is ineffective.

- BCL-2 Inhibitors (e.g., Venetoclax): Venetoclax is an oral drug that directly targets and inhibits the anti-apoptotic protein BCL−2. This allows the cell to resume its programmed cell death (apoptosis). It is often given in combination with an anti-CD20 antibody (e.g., Obinutuzumab) as fixed-duration therapy (e.g., 1-2 years), allowing patients to stop treatment and have periods off drug. Venetoclax requires a slow, weekly ramp-up (“Ramp-Up Phase”) to prevent rapid tumor cell death, which can lead to Tumor Lysis Syndrome (TLS). High-risk patients require TLS prophylaxis and close monitoring.

- Chemoimmunotherapy (CIT) (e.g., FCR: Fludarabine, Cyclophosphamide, Rituximab): CIT has largely been replaced by targeted agents due to superior efficacy and lower toxicity of the latter. It is now primarily reserved for younger, fit patients who have IgHV-Mutated (IgHV-M) disease, as these patients may achieve long-lasting, remission-free periods.

Management of Common Complications

CLL cells are functionally incompetent, leading to immunosuppression and an increased risk of complications.

- Transformation (Richter’s Transformation): In a small percentage of patients, CLL can transform into a more aggressive, high-grade lymphoma, most commonly Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL). This is an urgent diagnosis requiring aggressive, intensive chemotherapy.

- Infections: This is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality. Immunodeficiency stems from hypogammaglobulinemia, T-cell dysfunction, and often, the immunosuppressive effects of treatment. Patients should receive appropriate vaccinations (e.g., influenza, pneumococcal, COVID−19).

- Autoimmune Phenomena: CLL cells can occasionally produce autoantibodies, leading to:

- Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia (AIHA): Destruction of red blood cells by the patient’s own antibodies.

- Immune Thrombocytopenia (ITP): Destruction of platelets.

- Typically treated with corticosteroids, which are often effective.

Clinical Trials

Clinical trials are research studies that test new treatments for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Clinical trials can be a good option for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who have not responded to other treatments or who have relapsed after initial treatment.

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) Treatment Based on Stage

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) treatment depends on the stage of the disease, the patient’s age and health, and the presence of certain genetic mutations.

- Patients with early-stage CLL (Rai stage 0 or I): Patients with early-stage CLL may not need treatment right away. However, some patients with early-stage CLL may benefit from early treatment, such as targeted therapy.

- Patients with intermediate-stage CLL (Rai stage II or III): Patients with intermediate-stage CLL will eventually need treatment. Treatment options for intermediate-stage CLL include targeted therapy, immunotherapy, and chemotherapy.

- Patients with advanced-stage CLL (Rai stage IV): Patients with advanced-stage CLL will need treatment right away. Treatment options for advanced-stage CLL include targeted therapy, immunotherapy, and chemotherapy.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the first signs of chronic leukemia?

Chronic leukemia often progresses slowly, and in some cases, there might not be any noticeable symptoms in the early stages. However, some potential first signs of chronic leukemia to be aware of include:

- Feeling tired or fatigued: This can be a general feeling of exhaustion or lack of energy that persists even after rest.

- Unexplained weight loss: This can occur even if your appetite remains normal.

- Frequent infections: Chronic leukemia can weaken your immune system, making you more susceptible to infections.

- Easy bruising or bleeding: This can happen due to a decrease in platelets, which are important for blood clotting.

- Pain or fullness in the upper left abdomen: This can be caused by an enlarged spleen, a common finding in some types of chronic leukemia.

- Swollen lymph nodes: These are painless lumps that may appear in your neck, armpits, or groin.

It’s important to note that these symptoms can also be caused by other conditions.

What is the survival rate for lymphocytic leukemia?

The survival rate for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) depends on various factors, but here’s a general breakdown:

- Overall: Around 87% of people with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) live for 5 or more years following diagnosis. This statistic is based on data for people diagnosed in recent years, indicating potential improvements in treatment and outcomes.

- Age: Younger patients tend to have a better prognosis than older patients.

- Stage: Earlier stages of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) generally have a better outlook compared to advanced stages.

- Other health factors: Overall health and presence of other medical conditions can influence survival rates.

Is chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) aggresive?

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) can be aggressive in some cases, but it’s more commonly classified as a slow-growing cancer.

- Indolent CLL: This is the most common form of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), characterized by slow growth. Many patients with indolent chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) may not experience any symptoms for years and might not even require immediate treatment. Regular monitoring is crucial for these patients.

- Aggressive CLL: This less frequent form of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) grows more rapidly and requires prompt treatment. Signs of aggressive chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) might include:

- Increased number of abnormal lymphocytes in the blood

- Enlarged spleen or lymph nodes

- Low red blood cell count (anemia)

- Low platelet count (thrombocytopenia)

- Frequent infections

Factors Influencing Aggressiveness

- Genetic mutations: The specific genetic mutations present in the cancerous cells can impact their growth rate. Studies have revealed that chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients with specific genetic abnormalities, including chromosomal translocations, complex karyotypes, and high genomic complexity detected by SNP arrays, tend to have a more aggressive form of the disease. This aggressive chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) progresses rapidly and offers shorter remission periods after treatment.

- Lymphocyte doubling time: This refers to the time it takes for the number of cancerous lymphocytes to double. A shorter doubling time suggests a more aggressive form of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

- Presence of certain proteins: The presence or absence of specific proteins on the surface of the cancerous lymphocytes can indicate a more aggressive course. For example, patients with unmutated IGHV CLL cells typically have more aggressive disease than patients with CLL cells that express a mutated IGHV.

Can a patient live a normal life with CLL?

Yes, many patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) can live normal or near-normal lives, especially those diagnosed with the indolent form.

Type of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)

- Indolent CLL: This is the most common form, characterized by slow growth. Many patients with this type might not experience symptoms for years and may not require immediate treatment. Regular monitoring allows them to maintain a normal life with minimal disruption.

- Aggressive CLL: This less frequent form requires prompt treatment, which can sometimes involve side effects that might impact daily activities. However, with advancements in treatment, many patients with aggressive chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) can still achieve a good quality of life.

What happens if chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is not treated?

If chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is left untreated, the potential consequences can vary depending on the initial aggressiveness of the cancer and the individual’s overall health.

- Progression of the Disease: Untreated, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) will likely progress over time. The abnormal lymphocytes in the bone marrow continue to multiply, crowding out healthy blood cells.

- Impact on Blood Counts: This can lead to a decrease in red blood cells (anemia), causing fatigue, weakness, and shortness of breath. There might also be a decrease in white blood cells (leukopenia), making the body more susceptible to infections. Additionally, a reduction in platelets (thrombocytopenia) can increase the risk of bleeding.

- Enlarged Spleen and Lymph Nodes: As the number of abnormal lymphocytes increases, the spleen and lymph nodes, which are part of the immune system, can become enlarged due to an overactive attempt to filter the cancerous cells.

- Increased Risk of Infections: The decrease in healthy white blood cells can significantly weaken the immune system, making the body less able to fight off infections. These infections can become severe and even life-threatening.

- Bone Pain and Discomfort: In some cases, the cancerous cells can infiltrate the bones, leading to bone pain and discomfort.

- Transformation to a More Aggressive Form: Although rare, untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) can transform into a more aggressive type of leukemia over time. This aggressive form requires more intensive treatment and might have a poorer prognosis.

Importance of Early Intervention

Early diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) are crucial to manage the disease effectively and prevent potential complications. Treatment can help control the growth of cancerous cells, minimize symptoms, and improve overall well-being.

Is there a cure for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)?

Currently, there isn’t a definitive cure for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) in the traditional sense of eliminating all cancerous cells from the body. However, significant advancements in treatment approaches offer hope for long-term management and potentially achieving a state similar to a cure for many patients.

How painful is chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)?

The experience of pain in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) can vary greatly from person to person. Some individuals might experience minimal or no pain throughout the course of the disease, while others might have more frequent or severe pain episodes.

However, as the disease progresses, some potential sources of pain can arise:

- Enlarged Spleen or Lymph Nodes: When the spleen and lymph nodes become enlarged due to an increased number of abnormal lymphocytes, they can press on surrounding organs or nerves, causing discomfort or dull aches in the upper left abdomen or other areas depending on the location of the enlarged lymph nodes.

- Bone Marrow Infiltration: In some cases, cancerous cells can infiltrate the bone marrow, leading to bone pain. This pain can be dull or achy and might worsen with activity.

- Secondary Conditions: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) can increase the risk of infections, and some infections themselves can be painful. Additionally, anemia, a common complication of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), can cause fatigue and a general feeling of weakness.

Can chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) turn into brain cancer?

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) itself isn’t known to directly turn into brain cancer. However, there are rare instances where chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) can affect the central nervous system (CNS), which includes the brain and spinal cord.

CLL Involvement in the CNS

- In rare cases (between 0.8% and 7% depending on autopsy studies), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) cells can migrate to the CNS and cause neurological symptoms. This isn’t necessarily due to cancerous transformation, but rather the presence of abnormal lymphocytes within the brain or spinal cord.

- Symptoms can vary depending on the location of the chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) cells within the CNS and might include headaches, seizures, weakness, numbness, or problems with balance.

- This CNS involvement is often treatable with medications or radiation therapy directed at the brain or spinal cord.

Richter’s Syndrome

- In even rarer instances (2-10% of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) can transform into an aggressive lymphoma called Richter’s syndrome. This is a distinct type of cancer, and while it can affect the lymph nodes and other organs, it can also develop within the brain.

- Richter’s syndrome typically progresses rapidly and requires specific treatment approaches for aggressive lymphomas.

Is chronic lymphocytic leukemia fatal?

While chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) itself might not be fatal, if left untreated, it can lead to complications that can be life-threatening. These include:

- Severe infections due to a weakened immune system

- Uncontrolled bleeding due to low platelet count

- Anemia causing shortness of breath and fatigue

- Bone pain and damage from infiltration by cancerous cells

Is chronic lymphocytic leukemia genetically inherited?

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia has a genetic basis, but it’s not typically inherited in a straightforward manner. Multiple factors, including genetic predisposition and environmental influences, work together to increase the risk of developing chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Research continues to explore the complex interplay of genetics and other factors in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) development.

What are the signs that the chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is getting worse?

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) progresses slowly, and some people with indolent chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) might not experience any worsening symptoms for years. However, there are signs that can indicate the chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) might be getting worse. Here are some to watch for:

- Increased Fatigue: Extreme fatigue and persistent weakness can be a sign that the cancerous cells are multiplying and crowding out healthy blood cells in the bone marrow. This can significantly impact daily activities and energy levels.

- Frequent Infections: A healthy immune system relies on white blood cells to fight infections. As chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) progresses, white blood cell count can decrease, making the patient more susceptible to infections. These infections might be more frequent, severe, and take longer to heal.

- Uncontrolled Bleeding: A decrease in platelets (thrombocytopenia) is a potential complication of worsening chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Platelets are essential for blood clotting, and a low count can lead to easy bruising or bleeding, even from minor injuries.

- Weight Loss: Loss of appetite and difficulty absorbing nutrients can occur due to an enlarged spleen or other complications associated with advancing chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). This can lead to unintended weight loss.

- New or Worsening Bone Pain: Bone pain can be a sign of cancerous cells infiltrating the bone marrow. This pain might be persistent, worsen with activity, and be more pronounced in specific areas like the hips, ribs, or back.

- Enlarged Spleen or Lymph Nodes: While enlargement can occur in early stages of CLL, a noticeable increase in the size of the spleen or lymph nodes might indicate worsening of the disease. These enlarged organs can cause discomfort or pain and potentially affect nearby organs.

- Shortness of Breath or Dizziness: Anemia, a common complication of worsening chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), can lead to shortness of breath, dizziness, and pale skin due to a lack of healthy red blood cells to carry oxygen throughout the body.

Glossary of Medical Terms

- BTK (Bruton Tyrosine Kinase): A non-receptor tyrosine kinase essential for B-cell signaling and survival; a key target for modern Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) therapy.

- BCL-2 (B-cell lymphoma 2): An anti-apoptotic protein overexpressed in CLL cells, inhibiting programmed cell death (apoptosis). It is the target of the drug Venetoclax.

- IGHV Mutational Status: The state of somatic hypermutation in the immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region. Unmutated (U-CLL) is associated with aggressive disease and is a poor prognostic factor.

- del(17p) / TP53 Mutation: A deletion on the short arm of chromosome 17, which contains the crucial tumor suppressor gene TP53. This is the highest-risk genetic feature, conferring resistance to chemotherapy.

- Lymphocyte Doubling Time (LDT): The time required for the absolute lymphocyte count to double. An LDT of less than 6–12 months is often an indication to consider treatment initiation.

- Chemoimmunotherapy (CIT): The historical treatment standard combining chemotherapy (e.g., Fludarabine) with a monoclonal antibody (e.g., Rituximab). Now largely replaced by targeted therapy.

- Richter Transformation (RT): The rare but critical transformation of CLL into an aggressive lymphoma, most commonly Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL).

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, Caligaris-Cappio F, Dighiero G, Döhner H, Hillmen P, Keating MJ, Montserrat E, Rai KR, Kipps TJ; International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia updating the National Cancer Institute-Working Group 1996 guidelines. Blood. 2008 Jun 15;111(12):5446-56. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-093906. Epub 2008 Jan 23. Erratum in: Blood. 2008 Dec 15;112(13):5259. PMID: 18216293; PMCID: PMC2972576.

- Eichhorst B, Robak T, Montserrat E, Ghia P, Niemann CU, Kater AP, Gregor M, Cymbalista F, Buske C, Hillmen P, Hallek M, Mey U; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Electronic address: [email protected]. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2021 Jan;32(1):23-33. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.09.019. Epub 2020 Oct 19. PMID: 33091559.

- Mukkamalla SKR, Taneja A, Malipeddi D, et al. Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. [Updated 2023 Mar 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-.

- Shadman M. Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: A Review. JAMA. 2023 Mar 21;329(11):918-932. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.1946. PMID: 36943212.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®). NCCN Guidelines for Patients® Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. 2022.

- Hallek M, Eichhorst B, Catovsky D. Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (Hematologic Malignancies) 1st ed. 2019 Edition (Springer).

- Carr JH. Clinical Hematology Atlas 6th Edition (Elsevier).

- Ouillette P, Fossum S, Parkin B, Ding L, Bockenstedt P, Al-Zoubi A, Shedden K, Malek SN. Aggressive chronic lymphocytic leukemia with elevated genomic complexity is associated with multiple gene defects in the response to DNA double-strand breaks. Clin Cancer Res. 2010 Feb 1;16(3):835-47. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2534. Epub 2010 Jan 19. PMID: 20086003; PMCID: PMC2818663.

- Michael Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, Caligaris-Cappio F, Dighiero G, Döhner H, Hillmen P, Keating M, Montserrat E, Chiorazzi N, Stilgenbauer S, Rai KR, Byrd JC, Eichhorst B, O’Brien S, Robak T, Seymour JF, Kipps TJ. iwCLL guidelines for diagnosis, indications for treatment, response assessment, and supportive management of CLL. 2018; 131 (25): 2745–2760.