TL;DR

Catastrophic Antiphospholipid Syndrome (CAPS) is a rare but life-threatening variant of Antiphospholipid Syndrome (APS). It’s thought to arise from a combination of existing APS (aPL), a precipitating event (like infection or surgery), and an amplifying factor (e.g., complement activation).

Pathogenesis ▾: aPL bind to phospholipids, activating endothelial cells, platelets, and the complement system, leading to a pro-thrombotic state. Inflammatory cytokines play a significant role.

Key Clinical Features ▾: These include vascular thrombosis, thrombocytopenia, MAHA, and systemic symptoms like fever. Obstetric complications are also associated.

Diagnosis ▾: Requires a combination of clinical suspicion, laboratory testing (aPL, CBC, coagulation studies, etc.), and imaging studies. Antiphospholipid antibodies (LA, aCL, anti-β2GPI) are crucial for diagnosis. Multiple positive tests and IgG isotype are more concerning.

Differential Diagnosis ▾: CAPS must be differentiated from sepsis, DIC, TTP/HUS, HELLP syndrome, vasculitis, and other causes of multi-organ dysfunction.

Treatment ▾: Prompt and aggressive treatment is crucial. This includes anticoagulation (heparin then warfarin with a target INR of 3-4 often), high-dose corticosteroids, plasma exchange, IVIG, and sometimes Rituximab for refractory cases. Treating underlying precipitating factors (like infections) is also essential.

Management of Organ Dysfunction ▾: Supportive care for affected organs is critical, including respiratory support, cardiovascular support, renal support, neurological support, etc.

Prognosis: CAPS has a high mortality rate, but with prompt diagnosis and aggressive treatment, outcomes can be improved. Long-term anticoagulation is usually required.

*Click ▾ for more information

Introduction

Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS) is a rare, life-threatening variant of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), a systemic autoimmune disease characterized by the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL). While APS can cause a range of thrombotic and obstetric complications, catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome distinguishes itself by its rapid onset and multisystem involvement, affecting at least three organs or systems, often within a short period of days to weeks. This “triple hit” hypothesis suggests that catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome arises from the combination of a patient with antiphospholipid syndrome, a precipitating event (such as infection or surgery), and a second, amplifying “hit” (like complement activation) that triggers widespread microvascular thrombosis. The resulting widespread ischemia and organ damage make catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome a critical medical emergency requiring prompt recognition and aggressive treatment.

Antiphospholipid Syndrome

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is an autoimmune disorder that affects the blood’s clotting ability. It’s characterized by the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL), which are abnormal antibodies that mistakenly attack the body’s own cells. These antibodies can cause blood clots to form in both arteries and veins, leading to a variety of complications.

APS can manifest in a number of ways, including:

- Venous thrombosis: Blood clots in deep veins, often in the legs (deep vein thrombosis or DVT) or lungs (pulmonary embolism or PE).

- Arterial thrombosis: Blood clots in arteries, which can lead to stroke, heart attack, or other organ damage.

- Pregnancy complications: Recurrent miscarriages, stillbirths, premature births, and preeclampsia (high blood pressure during pregnancy).

- Other symptoms: Low platelet count (thrombocytopenia), livedo reticularis (a lacy rash), and neurological problems.

Antiphospholipid syndrome can occur on its own (primary APS) or in association with other autoimmune diseases, such as lupus (secondary APS). The severity of APS can vary widely, from mild to life-threatening.

Historical Context of Catastrophic Antiphospholipid Syndrome

Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS) was first described in 1992 by Dr. Ronald Asherson, who recognized a distinct subset of antiphospholipid syndrome patients with rapid-onset multi-organ failure due to widespread thrombosis.

Prior to Asherson’s description, these cases were likely misdiagnosed as other conditions, such as sepsis or disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). However, Asherson’s work highlighted the unique clinical picture of catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS), characterized by the involvement of multiple organs within a short period, often triggered by a precipitating event like infection or surgery.

The recognition of catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS) as a distinct entity has led to increased awareness and improved diagnostic criteria. This has allowed for earlier recognition and more aggressive treatment, ultimately improving outcomes for patients with this life-threatening condition.

Pathogenesis of Catastrophic Antiphospholipid Syndrome

The exact cause of catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS) is unknown, but it’s thought to be triggered by a combination of factors.

- Presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL)

- Triggering event: This could be an infection, surgery, or other medical condition.

- Additional factors: These may include genetic predisposition, complement activation (part of the immune system), and other environmental factors.

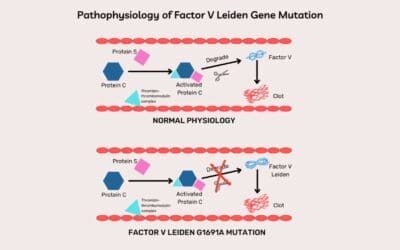

The pathogenesis of catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS) is complex and not fully understood. The proposed mechanism is that antiphospholipid antibodies (aPLs) bind to phospholipids on the surface of cells, such as endothelial cells and platelets. This binding activates the cells, leading to the release of pro-inflammatory and pro-coagulant factors. These factors promote further activation of the clotting system and the formation of blood clots. Complement activation amplifies the inflammatory and thrombotic processes leading to the formation of multiple blood clots in small blood vessels throughout the body. This can lead to decreased blood flow and damage to multiple organs, including the brain, lungs, kidneys, and heart.

Antiphospholipid Antibodies

In catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS), the primary drivers of the disease are autoantibodies, specifically antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL). These are misdirected antibodies that mistakenly target the body’s own phospholipids and phospholipid-binding proteins. While aPL are present in the broader spectrum of Antiphospholipid Syndrome (APS), they play a crucial role in the accelerated and widespread thrombosis seen in CAPS.

- Anticardiolipin antibodies (aCL): These are among the most commonly measured aPL. They target cardiolipin, a negatively charged phospholipid found in cell membranes, particularly on platelets and endothelial cells. aCL can be of IgG, IgM, or IgA isotype, with IgG being most strongly associated with thrombotic events. They can contribute to thrombosis by interfering with coagulation pathways, activating platelets, and damaging endothelial cells.

- Anti-β2 glycoprotein I antibodies (anti-β2GPI): β2GPI is a plasma protein that binds to phospholipids and plays a role in regulating coagulation. Anti-β2GPI antibodies are directed against this protein, particularly when it’s bound to phospholipids. These antibodies can disrupt the anticoagulant properties of β2GPI, promote platelet activation, and induce endothelial cell dysfunction, all contributing to a pro-thrombotic state. Like aCL, anti-β2GPI antibodies can be of different isotypes, and their presence, especially IgG, is strongly linked to thrombosis.

- Lupus anticoagulant (LA): Despite its name, LA is not an anticoagulant in vivo. Instead, it’s an in vitro phenomenon observed in certain coagulation tests. LA interferes with the phospholipid-dependent coagulation cascade, leading to a prolonged clotting time in these tests. However, in vivo, LA is associated with an increased risk of thrombosis. The mechanism by which LA contributes to thrombosis is complex and likely involves interactions with various coagulation factors and endothelial cells. It’s an important marker for APS, including CAPS, and can be present even when aCL and anti-β2GPI are negative.

It’s important to note that the presence of one or more of these aPL is a key criterion for the diagnosis of APS, including CAPS. However, the presence of aPL alone is not sufficient for the development of CAPS. As mentioned before, a “second hit” (e.g., infection) and a “third hit” (e.g., complement activation) are likely required to trigger the catastrophic cascade. Furthermore, the levels and persistence of these autoantibodies can fluctuate, and their correlation with disease activity in CAPS is not always straightforward. Research continues to explore the precise roles of different aPL isotypes and their interactions in the complex pathogenesis of CAPS.

Role of inflammatory cytokines in CAPS

Inflammatory cytokines play a significant role in the pathogenesis of catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS). These signaling molecules, released by various immune cells, contribute to the amplification of the inflammatory and thrombotic processes characteristic of catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS).

- TNF-α: This pro-inflammatory cytokine promotes endothelial cell activation, tissue factor expression (initiating the clotting cascade), and the release of other inflammatory mediators.

- IL-1β: Similar to TNF-α, IL-1β contributes to endothelial activation, promotes the production of procoagulant factors, and enhances the inflammatory response.

- IL-6: This cytokine is a major driver of the acute phase response and plays a role in B-cell activation and antibody production, including the production of aPLs.

These cytokines, along with others, create a pro-inflammatory environment that exacerbates the thrombotic diathesis in catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS). They contribute to:

- Endothelial dysfunction: Cytokines damage the inner lining of blood vessels, making them more prone to clot formation.

- Platelet activation: Cytokines activate platelets, increasing their aggregation and contribution to thrombus formation.

- Complement activation: Cytokines can activate the complement system, further amplifying the inflammatory and thrombotic cascades.

Genetic predisposition and environmental triggers

While the exact cause of catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS) remains elusive, it is likely a combination of genetic predisposition and environmental triggers that contribute to its development.

- Genetic predisposition: Certain genetic factors may increase an individual’s susceptibility to antiphospholipid syndrome and consequently, catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS). However, no specific gene has been definitively identified as a cause of catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS). Research is ongoing to explore potential genetic associations, such as variations in genes involved in immune regulation, coagulation, and complement activation.

- Environmental triggers: Various environmental factors can trigger or exacerbate CAPS in individuals with APS. These triggers can include:

- Infections: Bacterial, viral, or fungal infections can activate the immune system and trigger a “cytokine storm,” potentially leading to CAPS.

- Surgery: Surgical procedures can also activate the immune system and increase the risk of thrombosis, particularly in individuals with underlying APS.

- Medications: Certain medications, such as oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy, may increase the risk of thrombosis in some individuals with antiphospholipid syndrome, potentially predisposing them to catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS).

- Other factors: Other potential triggers include pregnancy, trauma, and autoimmune diseases.

It is important to note that catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS) is a rare condition, and most individuals with antiphospholipid syndrome will not develop it. However, understanding the role of inflammatory cytokines, genetic predisposition, and environmental triggers can aid in risk assessment and potentially lead to preventative measures.

Clinical Features of Catastrophic Antiphospholipid Syndrome (CAPS)

Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS) is a severe, rapidly progressive condition characterized by widespread thrombosis affecting multiple organs. Its clinical presentation is highly variable due to the diverse range of organ systems involved.

Vascular Manifestations (Thrombosis in any organ): This is the hallmark of CAPS. Thrombosis can occur in arteries, veins, or small vessels, leading to ischemia and infarction in various organs.

- Brain: Stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic), seizures, cognitive dysfunction, headache, visual disturbances.

- Heart: Myocardial infarction (heart attack), unstable angina, heart failure (due to myocardial ischemia or valvular involvement), pericarditis.

- Lungs: Pulmonary embolism (PE), acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), pulmonary hypertension. These can lead to severe respiratory distress.

- Kidneys: Acute kidney injury, often rapidly progressive, due to renal artery or vein thrombosis, or microvascular thrombosis within the kidneys. This can manifest as oliguria or anuria.

- Skin: Livedo reticularis (a net-like, purplish rash), skin necrosis, digital gangrene. These are often early manifestations.

- Gastrointestinal: Mesenteric ischemia (intestinal infarction), liver infarction, pancreatitis. Abdominal pain is a common symptom.

- Adrenal glands: Adrenal hemorrhage or infarction, leading to adrenal insufficiency.

- Other sites: Thrombosis can occur in virtually any organ, including the eyes (retinal vein occlusion), limbs (peripheral arterial thrombosis), and placenta (leading to obstetric complications).

Hematologic Manifestations

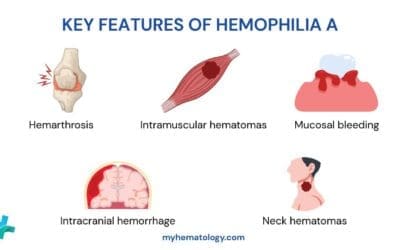

- Thrombocytopenia: Low platelet count, often severe, due to platelet consumption in the widespread thrombotic process.

- Microangiopathic Hemolytic Anemia (MAHA): Anemia caused by the destruction of red blood cells as they pass through small, thrombosed vessels. This is characterized by schistocytes (fragmented red blood cells) on the peripheral blood smear.

Systemic Manifestations

- Fever: Often present, and can be difficult to distinguish from infection, a common trigger for CAPS.

- Constitutional symptoms: Fatigue, malaise, weight loss.

Obstetric Complications

- Recurrent fetal loss: Especially in the second or third trimester.

- Preeclampsia/eclampsia: High blood pressure and protein in the urine during pregnancy.

- Placental insufficiency: Leading to fetal growth restriction or stillbirth.

Precipitating Factors

CAPS is often triggered by a “first hit” (the presence of aPL), a “second hit” (a precipitating event), and a “third hit” (further amplification of the process). Common precipitating factors include:

- Infections: Bacterial, viral, or fungal.

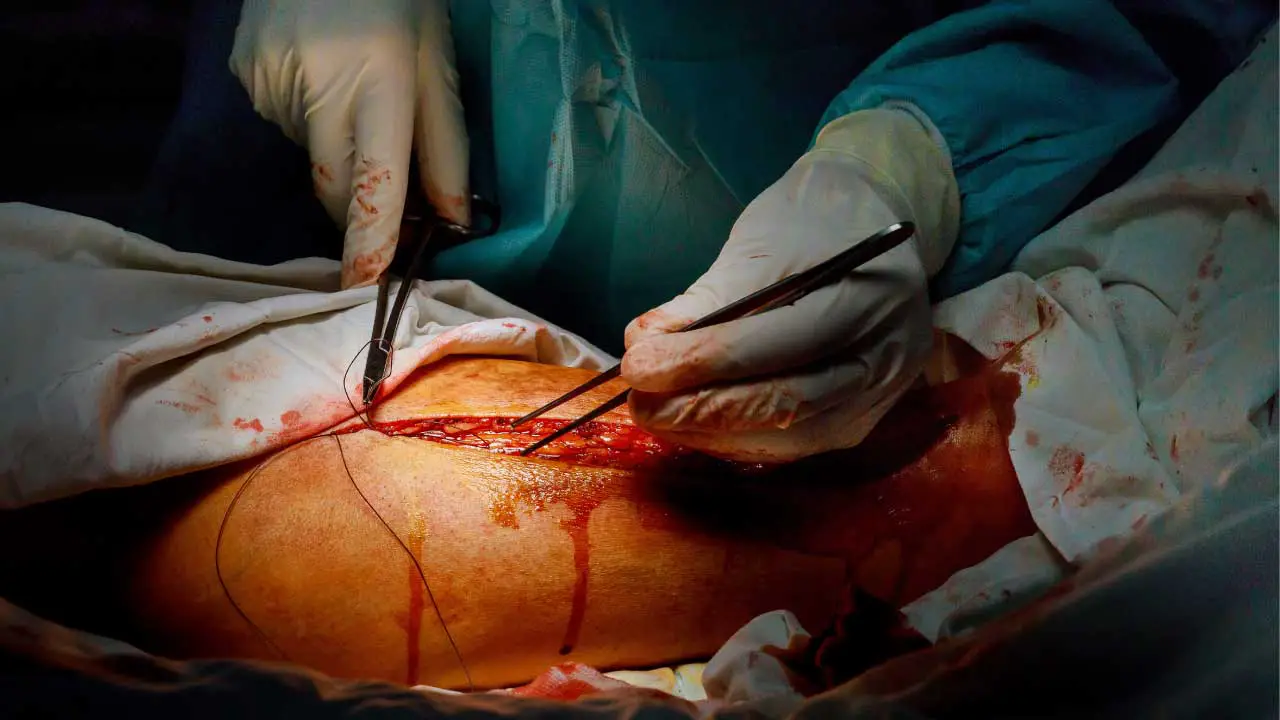

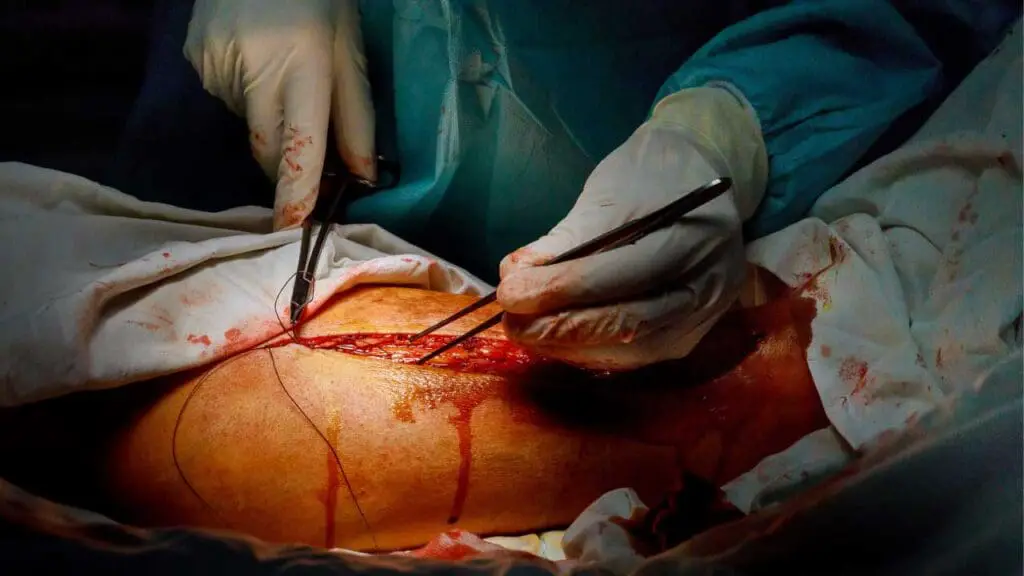

- Surgery: Any surgical procedure can trigger CAPS in susceptible individuals.

- Medications: Certain drugs, such as oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy.

- Other factors: Pregnancy, trauma, and other autoimmune diseases.

Important Considerations

- Rapid progression: The hallmark of CAPS is the rapid development of multi-organ failure.

- Variability: The clinical presentation can vary significantly depending on the organs involved.

- High mortality: CAPS is a life-threatening condition with a high mortality rate if not promptly recognized and treated.

Because of its rapid progression and multi-system involvement, CAPS requires a high degree of clinical suspicion and prompt intervention. Early recognition and aggressive treatment are crucial for improving patient outcomes.

Laboratory Investigations for CAPS

Diagnosing catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS) requires a combination of clinical suspicion and laboratory investigations. Because CAPS mimics other conditions, lab tests are essential to confirm the diagnosis and differentiate it from other causes of multi-organ dysfunction.

Antiphospholipid Antibody (aPL) Testing

This is crucial for diagnosing APS, including catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS).

- Lupus Anticoagulant (LA): This is a functional assay that detects antibodies that interfere with phospholipid-dependent coagulation tests. It’s important to note that despite its name, LA is associated with an increased risk of thrombosis in vivo. It’s highly specific for APS, although not always present.

- Anticardiolipin Antibodies (aCL): These antibodies target cardiolipin, a phospholipid found in cell membranes. They are measured by ELISA and can be of IgG, IgM, or IgA isotype. IgG aCL is most strongly associated with thrombotic risk.

- Anti-β2 Glycoprotein I Antibodies (anti-β2GPI): These antibodies target β2GPI, a protein that binds to phospholipids and regulates coagulation. Like aCL, they are measured by ELISA and can be of different isotypes. IgG anti-β2GPI is also strongly linked to thrombosis.

Important notes

- Multiple positive tests: The presence of multiple aPL (LA, aCL, anti-β2GPI) increases the likelihood of APS and the risk of CAPS.

- Isotypes: IgG aCL and anti-β2GPI are generally considered more clinically significant than IgM or IgA.

- Persistence: aPL should be persistently positive on at least two occasions, at least 12 weeks apart, to meet diagnostic criteria for antiphospholipid syndrome. However, in the acute setting of CAPS, this might not be possible.

Hematological Investigations

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): To assess for thrombocytopenia (low platelet count) and anemia, which are common in CAPS. A peripheral blood smear should be examined for schistocytes (fragmented red blood cells), indicative of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA).

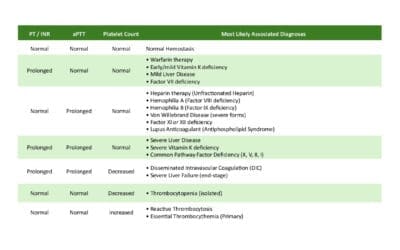

- Coagulation Studies:

- Prothrombin Time (PT) and Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (aPTT): These may be prolonged due to the presence of LA.

- D-dimer: This marker of fibrinolysis (breakdown of blood clots) is usually markedly elevated in CAPS due to widespread thrombosis.

Biochemical Investigations

- Renal Function Tests: To assess for acute kidney injury, which is common in CAPS due to renal thrombosis. Look for elevated creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN).

- Liver Function Tests: To evaluate for liver involvement, which can occur due to hepatic artery or vein thrombosis. Look for elevated liver enzymes (AST, ALT, ALP) and bilirubin.

- Cardiac Enzymes: If there is suspicion of myocardial infarction, check cardiac enzymes (troponin I or T).

Other Investigations

- Complement Levels: Complement activation plays a role in the pathogenesis of CAPS, and complement levels (C3, C4) may be decreased in some patients.

- Imaging Studies: Depending on the clinical presentation, imaging studies may be necessary to assess for thrombosis in specific organs:

- CT angiography: To visualize blood clots in arteries, such as pulmonary embolism or mesenteric ischemia.

- MRI: To assess for stroke or other neurological involvement.

- Echocardiography: To evaluate for cardiac involvement, such as valvular disease or myocardial dysfunction.

Investigations to rule out other conditions

- Blood cultures: To rule out sepsis, which can mimic CAPS.

- Autoimmune workup: To assess for other autoimmune diseases that may be associated with APS.

Differential Diagnosis of Catastrophic Antiphospholipid Syndrome (CAPS)

| Condition | Similarities | Differences | Key Lab Findings |

| CAPS | Multi-organ dysfunction, Thrombocytopenia, ↑ D-dimer | History of APS/aPL positivity,Widespread thrombosis,Often triggered by event | Positive aPL (LA, aCL, anti-β2GPI), ↑ D-dimer, possible MAHA |

| Sepsis | Multi-organ dysfunction, Thrombocytopenia, ↑ D-dimer, Fever | Identifiable infection trigger, Negative aPL | ↑ WBCs, Positive blood cultures (often), ↑ D-dimer |

| DIC | Multi-organ dysfunction, Thrombocytopenia, ↑ D-dimer, Bleeding | Underlying cause (e.g. sepsis, trauma, malignancy), ↓ Fibrinogen, ↑ PT/aPTT | ↑ PT/aPTT, ↓ Fibrinogen, ↑ D-dimer |

| TTP/HUS | MAHA, Thrombocytopenia, Neurological/Renal involvement | TTP: ADAMTS13 deficiency; HUS: Often associated with Shiga toxin or complement dysregulation | ↓ ADAMTS13 (TTP), MAHA, Negative aPL (typically) |

| HELLP Syndrome | Thrombocytopenia, ↑ Liver enzymes, Multi-organ dysfunction | Pregnancy-associated (usually 3rd trimester) | ↑ Liver enzymes, ↓ Platelets, Possible aPL |

| Vasculitis | Multi-organ involvement, Inflammation, Skin rash, Renal/Neuro involvement | Inflammation of blood vessel walls, Biopsy may show vasculitis, Specific autoantibodies | May have specific vasculitis-associated antibodies |

| ARDS | Pulmonary manifestations, Respiratory distress | Various causes (infection, trauma, etc.), Negative aPL | CXR/CT findings consistent with ARDS |

Treatment and Management of CAPS

Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS) is a rare and life-threatening condition that requires prompt and aggressive treatment. The primary goals of treatment are to prevent further blood clots, support vital organ function, and suppress the immune system’s attack on the body’s own cells. The specific treatment plan for CAPS will be tailored to each individual patient based on their specific symptoms and medical history. Treatment is typically given in the hospital, often in the intensive care unit.

- Anticoagulants: These medications help prevent blood clots from forming. Heparin is usually given first, followed by warfarin or another oral anticoagulant. Warfarin is commonly used for long-term anticoagulation in catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS) patients who have stabilized. The target INR range of 3.0 – 4.0 is recommended for patients with CAPS, especially those with a history of arterial thrombosis or recurrent thrombotic events despite adequate anticoagulation. This higher range reflects the need for more intense anticoagulation to prevent recurrent or new clot formation in this high-risk population.

- Immunosuppressants: These medications suppress the immune system and reduce the production of antiphospholipid antibodies. Corticosteroids are commonly used, and other immunosuppressants may be added if needed.

- Plasma exchange: This procedure removes harmful antibodies from the blood and replaces them with healthy blood components.

- Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG): This treatment provides healthy antibodies that can help suppress the immune system and reduce inflammation.

- Other therapies: Depending on the specific symptoms and complications of catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS), other therapies may be needed, such as medications to lower blood pressure, treat heart failure, or support breathing.

In addition to medical treatment, supportive care is also important for people with catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS).

If a patient with catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS) does not respond adequately to these therapies, or if they experience repeated flares of the disease despite treatment, their case is considered refractory. Rituximab, a monoclonal antibody that targets B cells (a type of immune cell), is increasingly being considered as a therapeutic option in these refractory CAPS cases.

While the acute management focuses on stabilizing the patient and combating the hypercoagulable state, identifying and treating the trigger is essential for preventing further disease exacerbation and promoting recovery.

Treating the Underlying Cause

- Infections: If an infection is identified, appropriate antibiotics should be started promptly. The choice of antibiotics will depend on the suspected pathogen.

- Surgery: If surgery is identified as a trigger, it may be necessary to postpone elective surgeries until the patient is stabilized. In urgent cases, careful perioperative management is crucial.

- Medications: If a medication is suspected to be a trigger, it should be discontinued.

- Other conditions: If another underlying condition is identified, it should be treated accordingly.

The prognosis for catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS) varies depending on the severity of the condition and how quickly treatment is started. With prompt and aggressive treatment, many people with CAPS can recover. However, some people may experience long-term complications, such as organ damage or disability.

Management of Organ Dysfunction

Managing organ dysfunction is a critical component of treating catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS). Because CAPS involves widespread thrombosis and ischemia, multiple organs can be affected, requiring specific interventions to support their function and prevent further damage.

General Principles of Organ Support in CAPS

- Early recognition: Prompt recognition of organ dysfunction is crucial for timely intervention.

- Multidisciplinary approach: Management of organ dysfunction often requires a multidisciplinary approach involving specialists from various fields (e.g., pulmonologists, cardiologists, nephrologists, neurologists, hematologists, intensivists).

- Supportive care: Supportive care is essential to maintain vital organ function and prevent further damage.

- Monitoring: Close monitoring of organ function is crucial to assess the effectiveness of treatment and make adjustments as needed.

Respiratory Support

- Oxygen therapy: Supplemental oxygen is crucial, especially if there’s pulmonary involvement (PE, ARDS). The delivery method will depend on the severity of respiratory distress.

- Mechanical ventilation: If respiratory failure develops, mechanical ventilation may be necessary to support breathing. This requires careful monitoring and management in an intensive care unit (ICU) setting.

- Treatment of PE: If pulmonary embolism is diagnosed, anticoagulation (heparin) is essential. In massive PE, thrombolytic therapy (clot-dissolving drugs) or surgical embolectomy (clot removal) may be considered.

Cardiovascular Support

- Hemodynamic monitoring: Close monitoring of blood pressure, heart rate, and cardiac output is essential to assess cardiovascular status.

- Vasopressors: If hypotension (low blood pressure) develops, vasopressors may be needed to maintain adequate perfusion to vital organs.

- Inotropic agents: If there’s evidence of myocardial dysfunction (heart failure), inotropic agents may be used to improve cardiac contractility.

- Management of arrhythmias: Cardiac arrhythmias can occur in catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS), requiring appropriate management.

Renal Support

- Fluid management: Careful fluid management is essential to maintain adequate hydration and electrolyte balance. Both overhydration and dehydration can worsen renal function.

- Renal replacement therapy (RRT): If acute kidney injury develops and is severe (e.g., anuria, electrolyte imbalances, uremia), RRT (hemodialysis or continuous venovenous hemofiltration) may be required to support kidney function.

Neurological Support

- Management of stroke: If ischemic stroke occurs, treatment may include thrombolytic therapy (if eligible) or antiplatelet agents. Supportive care for stroke patients is crucial.

- Seizure control: If seizures occur, anticonvulsant medications should be administered.

- Management of cognitive dysfunction: Cognitive impairment can occur in catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS). Supportive measures and rehabilitation may be necessary.

Hematological Support

- Transfusion support: If there’s severe thrombocytopenia or anemia, blood transfusions (platelets or red blood cells) may be necessary. However, transfusions should be used judiciously due to the risk of exacerbating thrombosis in some cases.

- Management of MAHA: Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA) is common in catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS). Treatment focuses on addressing the underlying cause and supporting red blood cell production.

Gastrointestinal Support

- Nutritional support: Enteral nutrition (feeding through a tube into the stomach or small intestine) is preferred if possible. Parenteral nutrition (intravenous feeding) may be necessary if enteral nutrition is not tolerated.

- Management of mesenteric ischemia: If mesenteric ischemia (intestinal infarction) occurs, prompt surgical intervention may be required to remove necrotic bowel.

Other Organ Support

- Adrenal insufficiency: If adrenal hemorrhage or infarction occurs, corticosteroids may be needed to treat adrenal insufficiency.

- Other organ involvement: Management of other organ dysfunction will depend on the specific organ affected.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Carmi O, Berla M, Shoenfeld Y, Levy Y. Diagnosis and management of catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome. Expert Rev Hematol. 2017 Apr;10(4):365-374. doi: 10.1080/17474086.2017.1300522. Epub 2017 Mar 13. PMID: 28277850.

- Fuentes Carrasco M, Mayoral Triana A, Cristóbal García IC, Pérez Pérez N, Izquierdo Méndez N, Soler Ruiz P, González González V. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome during pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021 Sep;264:21-24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2021.07.002. Epub 2021 Jul 7. PMID: 34273751; PMCID: PMC8260489.

- Ambati A, Knight JS, Zuo Y. Antiphospholipid syndrome management: a 2023 update and practical algorithm-based approach. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2023 May 1;35(3):149-160. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000932. Epub 2023 Mar 2. PMID: 36866678; PMCID: PMC10364614.