TL;DR

Arterial thrombosis forms when a clot blocks an artery, cutting off blood supply to vital organs.

- Risk factors ▾: Age, smoking, high cholesterol, diabetes, and others.

- Symptoms ▾: Sudden pain, weakness, numbness, and discoloration can signal a clot.

- Related disorders ▾:CAD, stroke, peripheral artery disease, aortic dissection, acute limb ischemia etc.

- Early diagnosis ▾: Blood tests and imaging is crucial for prompt action.

- Treatment ▾: Reperfusion (clot removal), pain management, and supportive care.

- Secondary prevention ▾: Lifestyle changes, medications, and managing underlying conditions to prevent future clots.

*Click ▾ for more information

Introduction

Thrombosis, in its simplest form, is the formation of a blood clot (thrombus) within the vascular system, specifically inside blood vessels. This clot acts as a physical barrier, partially or completely obstructing the flow of blood. Unlike extravascular clots that form outside the vessels, like a bruise, thrombi pose a significant threat by disrupting the vital delivery of oxygen and nutrients to organs and tissues. This blockage can lead to a variety of complications, ranging from mild discomfort to life-threatening conditions, depending on the location and severity of the clot.

Definition of Arterial Thrombosis

While thrombosis can occur anywhere in the vascular network, arterial thrombosis poses a unique and particularly dangerous threat. Imagine the aorta, the grand artery that pumps blood from the heart like a mighty river, suddenly choked by a clot. This isn’t just a traffic jam; it’s a dam, cutting off vital supplies to vital organs like the brain, heart, and limbs.

The significance of arterial thrombosis lies in its potential to cause ischemia, a state where tissues are deprived of oxygen and nutrients due to the blocked blood flow. This can have devastating consequences, ranging from acute events like heart attack or stroke to chronic conditions like peripheral artery disease, leading to amputations.

The consequences of arterial thrombosis vary depending on the location of the clot. In the heart, it can trigger a myocardial infarction, commonly known as a heart attack, where a portion of the heart muscle dies due to oxygen deprivation. In the brain, a clot can lead to a stroke, disrupting blood flow to brain cells and causing potentially debilitating neurological damage. In the legs, chronic arterial thrombosis can lead to peripheral artery disease, characterized by pain, numbness, and even gangrene if left untreated.

The potential for these devastating consequences underscores the importance of understanding the risk factors and mechanisms behind arterial thrombosis. Unlike venous thrombosis that often form in the slower-moving blood of the legs, arterial clots typically arise from a combination of three factors: endothelial injury, blood flow stasis, and hypercoagulability. Damage to the inner lining of the arteries (endothelium) can act as a trigger, while sluggish blood flow (stasis) and an increased tendency for blood to clot (hypercoagulability) provide the perfect storm for clot formation.

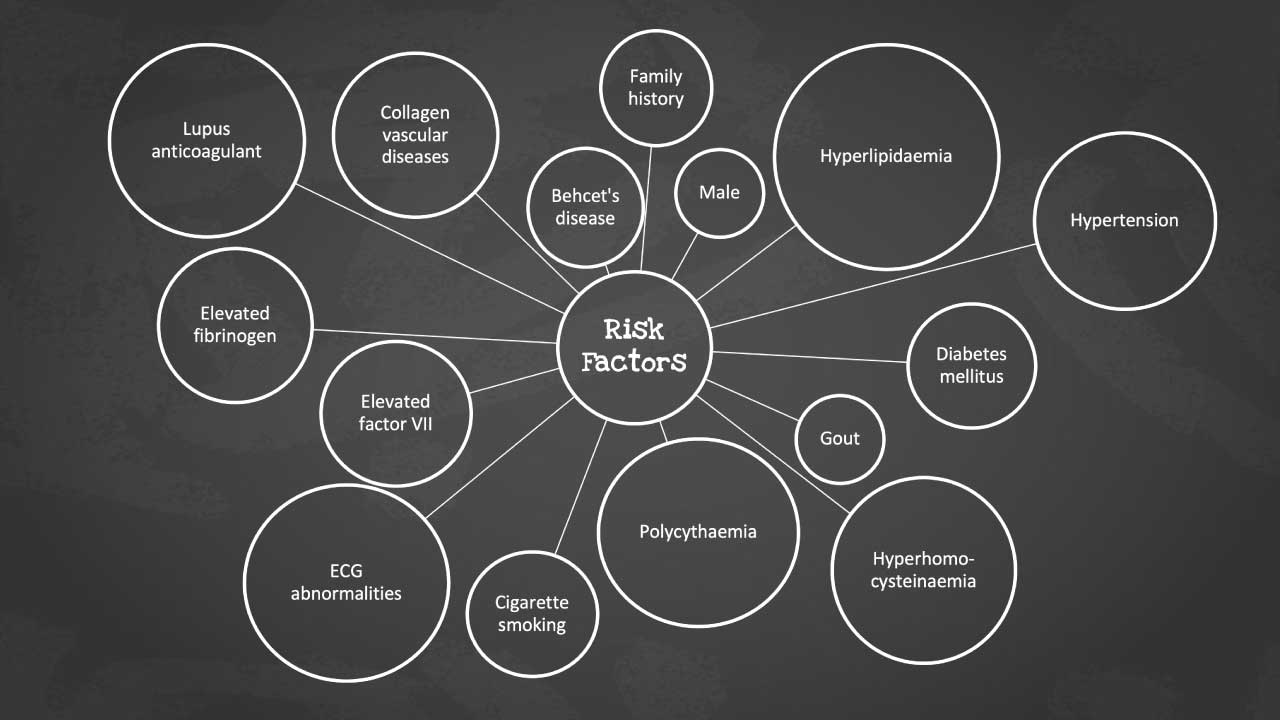

Risk Factors of Arterial Thrombosis

Imagine your blood vessels as a highway network, bustling with traffic but flowing smoothly. Arterial thrombosis disrupts this flow, like a sudden roadblock that can have serious consequences. But while its consequences can be dramatic, understanding the risk factors that pave the way for this clot formation is key to prevention and early intervention.

The risk factors for arterial thrombosis are related to the development of artherosclerosis. The identification of patients at risk is largely based on clinical assessment. These profiles have allowed pre-symptomatic assessment of young and apparently fit subjects and are valuable in counselling a change in lifestyle of for recommending medical therapy in individuals at risk. The Northwick Park Heart Study showed that elevated plasma levels of factor VII and fibrinogen are the strongest independent predictors of coronary events. Hyperhomocysteinemia has been recognized as a risk for peripheral and coronary arterial disease and stroke. Apart from these, there are many other types of risk factors for arterial thrombosis too.

Modifiable Risk Factors

- Age: As we age, our blood vessels naturally become less flexible and more prone to damage, increasing our susceptibility to thrombosis.

- Smoking: This notorious villain harms the endothelium, the inner lining of arteries, making it sticky and prone to clot formation.

- Diet: A diet high in saturated fat and cholesterol can contribute to the buildup of plaque in arteries, narrowing the passageway and slowing blood flow, while a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and fiber promotes healthy blood vessel function.

- Hypertension: Uncontrolled high blood pressure puts constant strain on the artery walls, increasing the risk of damage and thrombosis.

- Dyslipidemia: High levels of LDL cholesterol (“bad” cholesterol) and low levels of HDL cholesterol (“good” cholesterol) can contribute to plaque formation and clot development.

- Diabetes: This chronic condition damages blood vessels and disrupts the body’s ability to regulate blood sugar, making thrombosis more likely.

- Obesity: Excess weight puts additional strain on the cardiovascular system and increases inflammation, both of which contribute to thrombosis risk.

- Physical Inactivity: Regular exercise helps maintain healthy blood flow and reduces inflammation, both of which protect against thrombosis.

- Stress: Chronic stress can contribute to high blood pressure, inflammation, and unhealthy lifestyle choices, all of which increase thrombosis risk.

Non-modifiable Risk Factors

- Genetics: Some genetic variants can increase our susceptibility to thrombosis by affecting blood clotting factors or the structure of blood vessels.

- Family history: Having a family member with a history of arterial thrombosis increases your risk, suggesting a potential genetic component.

- Ethnicity: Certain ethnic groups are more prone to specific risk factors like high blood pressure or diabetes, which in turn can increase thrombosis risk.

- Gender: Men generally have a higher risk of arterial thrombosis than women, although the risk increases for women after menopause.

Acquired Risk Factors

- Medical conditions: Certain medical conditions like cancer, inflammatory diseases, and infections can increase inflammation and disrupt blood clotting, making thrombosis more likely.

- Medications: Some medications like oral contraceptives and hormone therapy can increase thrombosis risk, usually by affecting blood clotting factors.

- Trauma: Injuries to blood vessels can damage the endothelium and trigger clot formation.

- Surgery: Any surgical procedure, especially major surgeries, can increase the risk of thrombosis due to temporary changes in blood flow and inflammation.

Signs and Symptoms Related to Arterial Thrombosis

While arterial thrombosis often lurks silently within our vascular system, its presence can manifest in a variety of ways, from subtle whispers to thunderous alarms. Recognizing these signs and symptoms, both acute and chronic, is crucial for early intervention and preventing disastrous consequences.

Acute Signs of Arterial Thrombosis

The blood flow in an artery blocked by a clot can trigger an acute event, a sudden disruption with alarming symptoms.

- Pain: A sharp, intense pain is often the first sign, This can be severe and localized, depending on the affected artery. Chest pain in a heart attack, leg pain in peripheral artery disease, or excruciating headache in a stroke are all potential clues.

- Ischemia: The tissues downstream of the clot experience oxygen deprivation, leading to weakness, numbness, and even paralysis in the affected area.

- Discoloration: Pallor (paleness) or cyanosis (bluish discoloration) can occur in the affected area due to the reduced blood flow.

- Paresthesia: Pins and needles, numbness, or tingling sensations signal nerve damage from the lack of blood supply.

- Weakness: Muscles deprived of oxygen lose their strength, leading to difficulty moving or even complete paralysis.

- Loss of Function: Depending on the affected artery, the consequences can be dramatic, from slurred speech in a stroke to paralysis in a limb.

These acute signs are like flashing red lights, demanding immediate medical attention. Ignoring them can mean the difference between recovery and irreversible damage.

Chronic Symptoms of Arterial Thrombosis

Not all arterial thrombi announce themselves with such fanfare. Sometimes, the clot acts like a slow leak, gradually eroding health with chronic symptoms.

- Gradual Onset: The symptoms creep in insidiously, often mistaken for aging or overexertion until they become undeniable.

- Recurrent Pain: This could be a nagging ache or a sharp twinge, occurring in the affected area, especially with exertion.

- Claudication: This refers to leg pain that occurs on exertion and disappears with rest.

- Coldness: The affected area may feel cold to the touch due to reduced blood flow.

- Ulceration: In severe cases, chronic ischemia can lead to skin breakdown and ulcer formation.

Virchow’s Triad

Imagine a three-legged stool, each leg representing a crucial element of a stable structure. In the world of blood flow, that stool is Virchow’s Triad, a concept that explains the formation of blood clots (thrombi) within arteries. Each leg of this triad represents a factor that, when present in excess or imbalance, can tilt the balance towards thrombosis.

Endothelial Injury

The endothelium, the smooth inner lining of arteries, ensures smooth flow and preventing unwanted blood clot formation. When this lining gets damaged, it becomes rough and sticky, like Velcro attracting platelets and other clotting factors. This damage can be caused by:

- High blood pressure: This constant pressure wears down the endothelium, making it more susceptible to damage.

- Smoking: Cigarette smoke contains toxins that directly harm the endothelium, increasing inflammation and clot formation.

- Atherosclerosis: The buildup of plaque in arteries can irritate and damage the endothelium.

- Dyslipidemia: High levels of LDL cholesterol (“bad” cholesterol) can damage the endothelium and promote plaque buildup.

- Diabetes: This chronic condition disrupts blood flow and weakens the endothelium, making it more prone to injury.

- Infections: Certain infections can damage the endothelium, especially in smaller arteries.

- Autoimmune diseases: Conditions like lupus can attack the endothelium, increasing its vulnerability.

- Physical trauma: Injuries to blood vessels can directly damage the endothelium, triggering clot formation.

Blood Flow Stasis

Imagine a slow-moving river; debris is more likely to accumulate in stagnant areas. This sluggishness, known as stasis, allows blood cells to linger longer in one place, increasing the chance of them clumping together and forming a clot. Factors contributing to stasis include:

- Atherosclerosis: Plaque buildup in arteries narrows the passageway, slowing blood flow.

- Varicose veins: These enlarged, twisted veins have sluggish blood flow, increasing the risk of thrombosis.

- Prolonged bed rest or immobilization: Lack of movement can lead to blood pooling and stasis in the legs.

- Heart failure: This condition weakens the heart’s pumping ability, leading to reduced blood flow and stasis.

- Certain medications: Some medications, like diuretics, can thicken the blood and slow its flow.

Hypercoagulability

Think of blood as a delicate balance between clotting and flowing. Hypercoagulability, or an increased tendency for blood to clot, tips this balance towards the formation of unwanted thrombi. Factors promoting hypercoagulability include:

- Genetic factors: Certain genetic mutations can increase the risk of excessive clotting.

- Medical conditions: Cancer, inflammatory diseases, and hormonal imbalances can all disrupt the normal balance of clotting factors.

- Pregnancy and childbirth: These physiological changes increase the risk of blood clots.

- Smoking: As mentioned earlier, smoking promotes inflammation and clot formation.

- Certain medications: Hormone therapy and some birth control pills can increase the risk of clotting.

Remember, Virchow’s Triad isn’t a simple checklist; it’s a complex interplay of these three factors. Often, a combination of two or even all three elements contributes to the formation of arterial thrombi.

Alternative and evolving theories of thrombosis

While Virchow’s Triad has stood as the cornerstone of understanding thrombosis for centuries, emerging research and clinical observations have led to alternative and evolving theories that paint a more nuanced picture of clot formation. Here’s a peek into these theories:

The Response to Injury Hypothesis

This theory expands on Virchow’s Triad by emphasizing the dynamic interplay between endothelial injury and the body’s inflammatory response. It suggests that endothelial damage triggers an inflammatory cascade, attracting immune cells like neutrophils and platelets. These immune cells, along with the damaged endothelium, release inflammatory mediators that further promote clot formation. This broader perspective highlights the role of inflammation in thrombosis, potentially opening doors for new therapeutic strategies targeting inflammatory pathways.

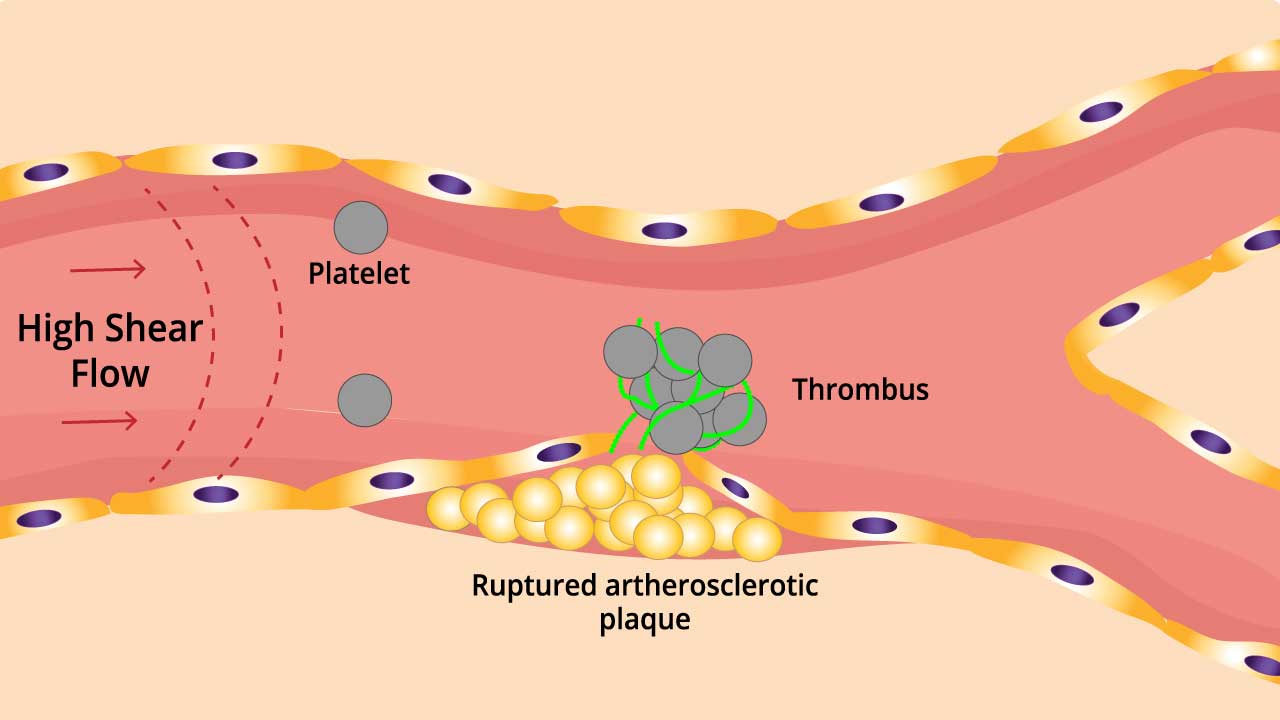

The Shear Stress Hypothesis

This theory focuses on the impact of blood flow dynamics on clot formation. It suggests that areas of low shear stress (slow or turbulent flow) within the vasculature promote platelet aggregation and activation, leading to thrombus formation. This can occur in areas of plaque buildup or vessel bifurcations where blood flow patterns are disrupted. Understanding how shear stress influences clot formation could lead to the development of devices or medications that modify blood flow patterns and prevent thrombosis.

The Virchow Plus Hypothesis

This theory acknowledges the limitations of Virchow’s Triad by adding additional factors that contribute to thrombosis. These include genetic predisposition, specific protein and enzyme abnormalities, and environmental factors like air pollution and stress. By considering these additional elements, this hypothesis provides a more comprehensive framework for understanding the complex web of factors that contribute to clot formation.

The Role of Microcirculation

Recent research suggests that thrombus formation might not be limited to large arteries but could also occur in the intricate network of microscopic vessels. This “microthrombosis” is increasingly recognized as a potential contributor to various diseases, including organ failure and chronic inflammatory conditions. Understanding the mechanisms of microthrombosis could lead to the development of novel diagnostic and therapeutic tools for these complex diseases.

These are just a few examples of the evolving theories around thrombosis. As research continues, our understanding of this complex process will undoubtedly be further refined. The key takeaway is that while Virchow’s Triad remains a valuable framework, acknowledging the contributions of alternative and evolving theories is crucial for developing more effective strategies for preventing and treating thrombosis.

Pathophysiology of Arterial Thrombosis

Imagine a peaceful river of blood flowing through the intricate network of your arteries. Suddenly, a disturbance ripples through the current – endothelial injury, sluggish flow, or a hyperactive clotting system. This disturbance triggers a cascade of events, culminating in the formation of a fibrin clot, a potentially life-threatening dam in the arterial highway. Let’s delve into the pathophysiology of this cascade, exploring the roles of key players and the unique features of arterial thrombosis.

Clot Formation

- Initiation: Clot formation begins with endothelial injury, often due to atherosclerosis, inflammation, or trauma. This injury exposes underlying collagen, a potent platelet activator.

- Platelet Adhesion and Activation: Sticky platelets, the first responders, adhere to the exposed collagen. Activated platelets release a plethora of signals, attracting more platelets and initiating the coagulation cascade.

- Coagulation Cascade: A cascade of protein activations ensues, culminating in the formation of thrombin, the enzyme responsible for converting fibrinogen into fibrin, the mesh-like structure of a clot.

- Fibrin Clot Formation: Thrombin cleaves fibrinogen into fibrin monomers, which then polymerize into a stable fibrin network, trapping platelets and red blood cells, forming a clot that blocks the artery.

The Key Players

- Platelets: These sticky cells act as the initial bridge, forming the first layer of the clot. Their activation and aggregation are crucial for the process.

- Coagulation Factors: These proteins, like actors in a play, work in a specific order to convert fibrinogen into fibrin, the main building block of the clot.

- Complement System: This immune system component adds another layer of reinforcement, stabilizing the fibrin clot and preventing its breakdown.

Arterial vs. Venous Thrombosis

While the basic principles of clot formation are similar in arteries and veins, key differences exist:

- Flow dynamics: Arterial flow is faster and more turbulent, favoring rapid platelet aggregation and clot formation. Venous flow is slower, allowing for a slower, more pro-coagulant environment.

- Clot composition: Arterial clots are typically platelet-rich and fibrin-rich, making them more stable and resistant to breakdown. Venous clots are often looser, containing more red blood cells and fibrin, making them more prone to dislodging and traveling as emboli.

- Triggering factors: Arterial thrombosis often arises from endothelial injury or hypercoagulability, while venous thrombosis is more commonly associated with stasis and hyperviscosity of blood.

Understanding the clot formation in arteries, the unique roles of platelets, coagulation factors, and the complement system, and the key differences between arterial and venous thrombosis is crucial for developing effective strategies for prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of these potentially devastating events.

Disorders Related to Arterial Thrombosis

Arterial thrombosis isn’t just a singular event; it can lead to a cascade of disorders depending on the affected artery and the extent of the blockage. Here’s a quick look of some of the most common culprits:

1. Coronary Artery Disease (CAD): CAD narrows the heart’s own supply arteries, often via atherosclerosis. When a clot forms here, it can trigger a myocardial infarction (heart attack), robbing the heart of vital oxygen, leading to tissue damage and potentially fatal consequences.

2. Cerebrovascular Accident (Stroke): When a clot blocks arteries supplying the brain, the result is a stroke. Sudden loss of blood flow can deprive brain cells of oxygen and nutrients, leading to paralysis, speech difficulties, or cognitive impairment, depending on the affected area.

3. Peripheral Artery Disease (PAD): PAD targets arteries in the legs, causing them to narrow and weaken. Clots here can lead to claudication (pain on walking), leg ulcers, and even gangrene, requiring amputation in severe cases.

4. Aortic Dissection: This dramatic event sees the inner layer of the aorta, our body’s largest artery, tear, allowing blood to dissect its way between layers. Clots can form within this dissection, further disrupting blood flow and potentially leading to life-threatening complications.

5. Acute Limb Ischemia: This rapid loss of blood flow to an arm or leg often stems from a sudden arterial clot. Severe pain, coldness, and limb discoloration are warning signs, demanding immediate medical attention to prevent irreversible tissue damage and amputation.

6. Others.

Renal Artery Stenosis: Narrowed arteries supplying the kidneys can lead to high blood pressure and kidney damage.

Intestinal Ischemia: Clots in mesenteric arteries can deprive the intestines of blood, causing severe abdominal pain and tissue death.

Vision Loss: Clots in retinal arteries can block blood flow to the eye, leading to vision loss or blindness.

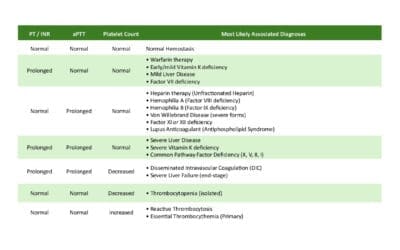

General Laboratory Tests Related to Arterial Thrombosis

While these general laboratory tests may indicate arterial thrombosis. Exact diagnoses and cause of the arterial thrombosis have to be elucidated with specific laboratory tests and imaging techniques depends on various factors like suspected location of the clot, clinical symptoms, and individual risk factors.

Blood Tests

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): This provides a snapshot of red and white blood cells, platelets, and hemoglobin levels. Decreased red blood cells (anemia) might suggest chronic blood loss due to arterial insufficiency, while elevated white blood cells could point towards inflammation associated with thrombosis.

- Coagulation Profile: This assesses the efficiency and balance of your clotting system. Tests like prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) measure how quickly your blood clots, while fibrinogen levels indicate the amount of material available for clot formation. Prolonged clotting times or elevated levels of certain clotting factors can suggest hypercoagulability, a risk factor for thrombosis.

- D-dimer: This marker is a byproduct of fibrin degradation, elevated levels indicating recent clot formation or breakdown. Elevated D-dimer levels can indicate recent clot formation, although other conditions can also cause them.

- Inflammatory Markers: Markers like C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) can be elevated in response to inflammation, which can contribute to thrombosis.

- Lipid Panel: This assesses cholesterol levels, as high levels can contribute to atherosclerosis, a major risk factor for thrombosis.

Imaging Techniques

- Angiography: This gold-standard technique uses contrast dye injected into arteries to visualize their structure and identify blockages caused by clots. Different types like X-ray angiography, CT angiography, and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) offer varying degrees of detail and spatial resolution.

- Doppler Ultrasound: This non-invasive technique uses sound waves to assess blood flow within arteries. It can detect blockages, measure blood flow velocity, and identify areas of stenosis (narrowing) that might increase thrombosis risk.

- CT Scan: This advanced imaging technique provides detailed cross-sectional images of blood vessels, allowing visualization of clots, aneurysms, and other vascular abnormalities.

- MRI: This versatile tool offers high-resolution images of both arteries and surrounding tissues, making it useful in diagnosing not only clots but also underlying conditions like atherosclerosis that contribute to thrombosis.

General Treatment and Management of Arterial Thrombosis

When arterial thrombosis strikes, swift action is critical. The focus of acute management is reperfusion: restoring blood flow to the affected area and minimizing tissue damage.

Reperfusion

- Thrombolysis: These clot-busting medications dissolve the clot, restoring blood flow. They are effective for early-stage clots but carry bleeding risks.

- Thrombectomy: This minimally invasive procedure uses catheter-based devices to physically remove the clot. It is preferred for larger clots or when thrombolysis is contraindicated.

Pain Management

Arterial thrombosis can cause agonizing pain. Painkillers, nerve blocks, and even spinal cord stimulation may be used to provide relief and improve patient comfort.

Supportive Care

Maintaining optimal blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen levels is crucial to support tissue recovery and prevent further complications.

Secondary Prevention

Once the immediate threat is addressed, preventing future clots becomes the priority. This involves:

1. Antiplatelets: These medications prevent platelets from sticking together and forming clots. Aspirin, clopidogrel, and prasugrel are commonly used.

2. Anticoagulants: These medications inhibit the clotting cascade, preventing further clot formation. Heparin and warfarin are common examples.

3. Lifestyle Modifications: Diet, exercise, smoking cessation, and weight management significantly reduce the risk of recurrent thrombosis.

4. Management of Underlying Risk Factors: Addressing conditions like hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia is crucial for long-term prevention.

Surgical Intervention: When Medicine Isn’t Enough

In some cases, reperfusion through medications or catheter-based procedures may not be feasible. This is where surgery comes in:

- Bypass surgery: A healthy blood vessel is rerouted around the blocked artery, creating a new pathway for blood flow.

- Stenting: A small expandable tube is inserted into the blocked artery to open it up and maintain blood flow.

- Endarterectomy: The surgeon removes the plaque and clot buildup from inside the artery to restore blood flow.

Early Diagnosis Saves Lives

Prompt diagnosis and intervention are the cornerstones of preventing irreversible damage. By understanding the symptoms and seeking immediate medical attention, we can turn the tide on this potentially life-altering threat.

Looking Ahead: Innovation in the Pipeline

Research is actively exploring new avenues for prevention and treatment, including:

- Targeted therapies to address specific genetic or protein abnormalities.

- Development of new antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications with fewer side effects.

- Gene therapy approaches to modify clotting factors and reduce risk.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How can you tell the difference between DVT and arterial thrombosis?

DVT (Deep Vein Thrombosis) and arterial thrombosis differ in location and symptoms. DVT occurs in veins, often the legs, causing swelling, pain, and redness. Arterial thrombosis happens in arteries, often leading to sudden, severe pain, numbness, or coldness in the affected limb. It’s crucial to seek immediate medical attention for both conditions.

What are the common sites of arterial thrombosis?

Common sites of arterial thrombosis include:

- Heart: Coronary arteries leading to a heart attack

- Brain: Carotid arteries leading to a stroke

- Legs: Arteries in the legs and feet

- Other organs: Less common sites include kidneys, intestines, and eyes.

What are the 5 P’s of arterial thrombosis?

The 5 P’s of arterial thrombosis are:

- Pain: Severe pain in the affected limb.

- Pallor: Unusually pale skin in the affected limb.

- Pulselessness: Absence or weak pulse in the affected limb.

- Paresthesia: Numbness or tingling in the affected limb.

- Paralysis: Loss of movement in the affected limb.

Why is aspirin used in arterial thrombosis?

Aspirin is used in arterial thrombosis prevention because it helps prevent blood platelets from sticking together and forming clots. By inhibiting platelet aggregation, aspirin reduces the risk of blood clots blocking arteries, which can lead to heart attacks and strokes. It’s important to note that aspirin should be used under medical guidance as it can increase the risk of bleeding.

How long do you use anticoagulant for arterial thrombosis?

The duration of anticoagulant use for arterial thrombosis varies depending on the specific case. Generally, it’s recommended for at least 3 to 6 months, but can be longer based on the patient’s risk factors, severity of the thrombosis, and the underlying cause. Regular monitoring and adjustments to the treatment plan are often necessary.

Is arterial thrombosis curable?

Arterial thrombosis itself isn’t curable, but its effects can be managed and prevented. While medications can dissolve existing clots and procedures like angioplasty or surgery can restore blood flow, the underlying conditions that led to the clot, such as atherosclerosis, often require ongoing management. The focus is on preventing future clots and minimizing damage to affected organs.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Saba HI, Roberts HR. Hemostasis and Thrombosis: Practical Guidelines in Clinical Management (Wiley Blackwell). 2014.

- DeLoughery TG. Hemostasis and Thrombosis 4th Edition (Springer). 2019.

- Keohane EM, Otto CN, Walenga JM. Rodak’s Hematology 6th Edition (Saunders). 2019.

- Kaushansky K, Levi M. Williams Hematology Hemostasis and Thrombosis (McGraw-Hill). 2017.

- Ten Cate H, Meade T. The Northwick Park Heart Study: evidence from the laboratory. J Thromb Haemost. 2014 May;12(5):587-92. doi: 10.1111/jth.12545. PMID: 24593861.