TL;DR

B-cell ALL, or B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, is an aggressive malignancy of immature B-cell precursors or lymphoblasts in the bone marrow.

- Demographics: Most common childhood cancer; has a bimodal age distribution (peaks at <5 and >65 years).

- Symptoms of B-cell ALL ▾: Bone marrow failure (anemia, infections, bleeding) and extramedullary spread (lymphadenopathy, CNS involvement).

- Diagnosis for B-cell ALL ▾: Requires ≥ 20% blasts in the marrow; confirmed via Flow Cytometry (CD19+, CD10+, TdT+).

- Treatment of B-cell ALL ▾: Divided into Induction, Consolidation, and Maintenance, with a growing reliance on targeted immunotherapies.

*Click ▾ for more information

What is acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)?

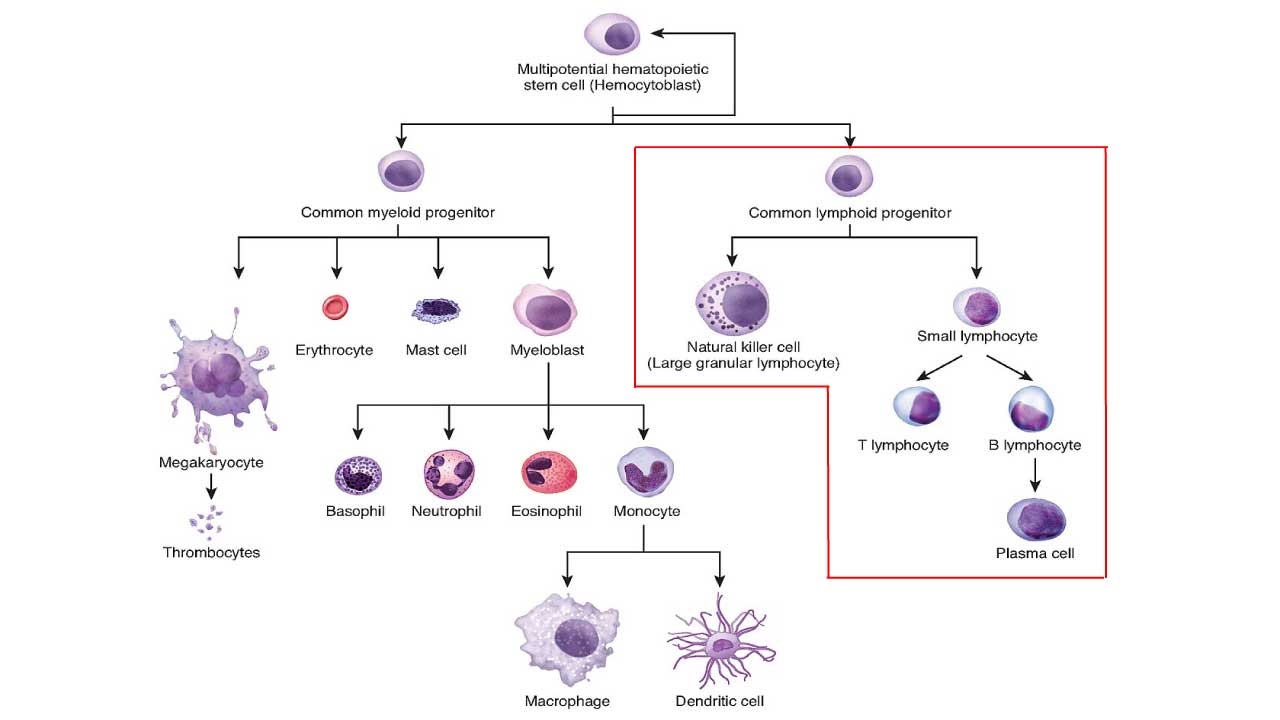

ALL can be divided into B-cell ALL and T-cell ALL . Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is a type of blood cancer that begins in the bone marrow. The bone marrow is the soft tissue inside the bones where blood cells are made. In ALL, the bone marrow makes too many immature lymphocytes called lymphoblasts.

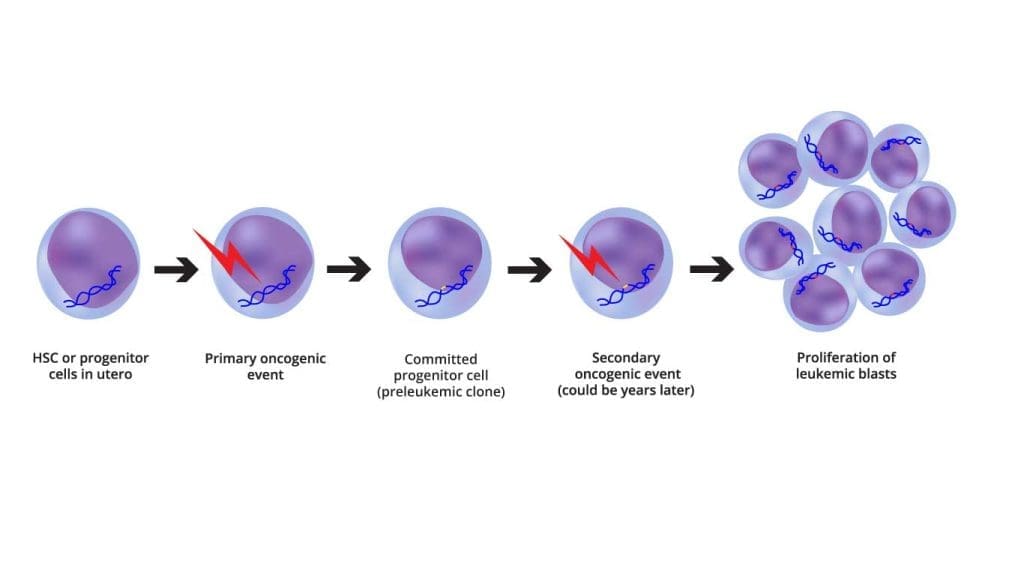

ALL is defined as an aggressive neoplasm of the lymphoid lineage caused by acquired somatic defects due to either inherited factors or infections e.g. viruses in early hematopoietic blasts that impede or significantly impair differentiation leading to accumulation of undifferentiated blasts in the marrow, spilling into the peripheral blood and infiltrate other tissues. Leukemic blasts are too immature to be functional and are prone to suppress or supplant the production of normal hematopoiesis causing pancytopenia.

ALL is the most common type of cancer in children, but it can also occur in adults. It is most common in children under the age of 5 and in adults over the age of 65.

B-cell ALL

B-cell ALL (B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia) is the most common type of ALL in children and adults, accounting for about 75-85% of all cases.

B-cell ALL (B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia) is caused by the uncontrolled growth of immature B cells. B cells are a type of white blood cell that helps the body fight infection. When B cells become cancerous, they can crowd out healthy blood cells in the bone marrow and bloodstream. This can lead to a number of problems, including fatigue, weakness, and an increased risk of infection.

Risk factors for B-cell ALL (B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia)

The exact cause of B-cell ALL (B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia) is unknown, but there are a number of risk factors that may increase the risk of developing the disease. These risk factors include:

- Age: B-cell ALL (B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia) is most common in children under the age of 5 and in adults over the age of 65.

- Gender: Males are slightly more likely to develop B-cell ALL (B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia) than females.

- Family history: People with a family history of B-cell ALL (B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia) are at an increased risk of developing the disease.

- Certain genetic conditions: People with certain genetic conditions, such as Down syndrome, Klinefelter syndrome, and Noonan syndrome, are at an increased risk of developing B-cell ALL (B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia).

- Exposure to radiation: Exposure to high levels of radiation, such as from X-rays or nuclear fallout, can increase the risk of developing B-cell ALL (B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia).

- Exposure to certain chemicals: Exposure to certain chemicals, such as benzene, has been linked to an increased risk of developing B-cell ALL (B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia).

Pathogenesis

Clinical Features of B-Cell ALL (B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia)

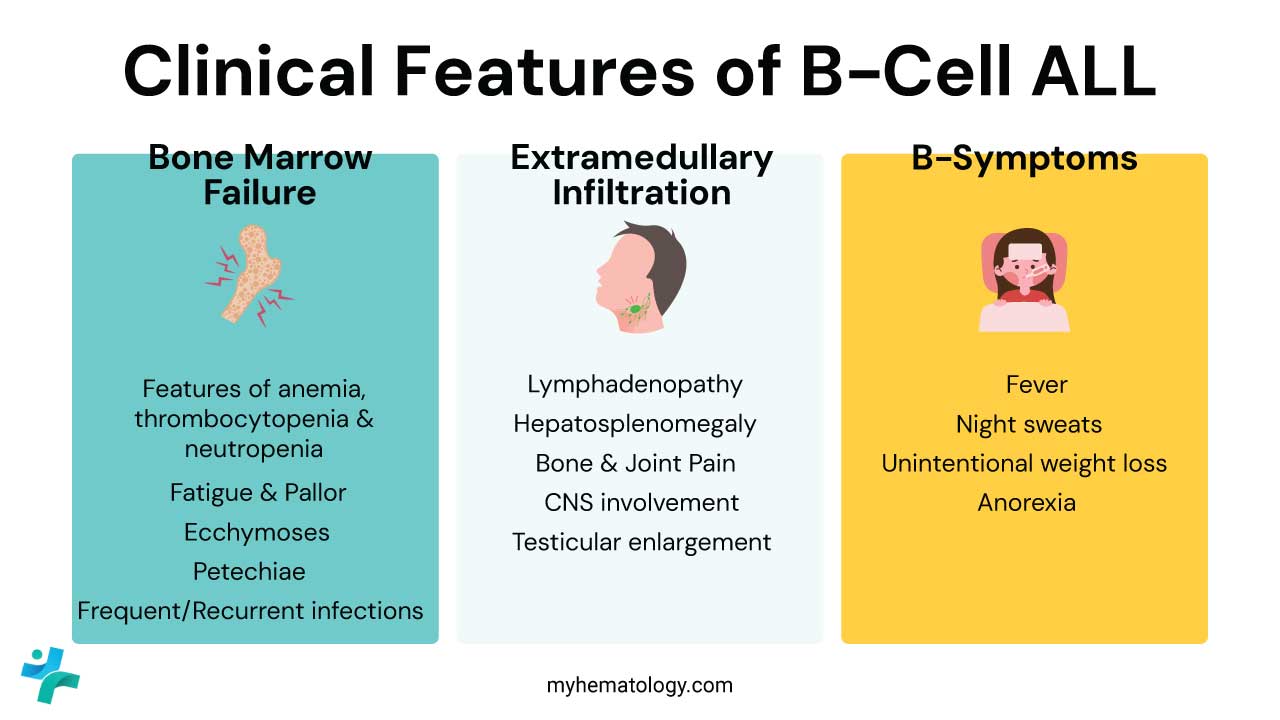

The clinical presentation of B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (B-cell ALL) is primarily driven by two factors: bone marrow failure (due to the “crowding out” of healthy cells) and extramedullary infiltration (the spread of blasts to other organs).

Bone Marrow Failure (The “Cytopenias”)

This is the most common reason patients seek medical attention. The rapid proliferation of lymphoblasts replaces normal hematopoietic tissue.

- Anemia (Low Red Blood Cells): Fatigue, generalized weakness, exertional dyspnea (shortness of breath), and noticeable pallor (paleness of the skin and conjunctiva).

- Thrombocytopenia (Low Platelets): Unexplained bruising (ecchymoses), small pinpoint red spots (petechiae), bleeding gums, and frequent epistaxis (nosebleeds).

- Neutropenia (Low Functional White Blood Cells): Frequent, persistent, or opportunistic infections. Patients often present with a high-grade fever, even if no specific site of infection is found.

Extramedullary Infiltration (Organ Involvement)

Unlike some other leukemias, B-cell ALL (B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia) has a high tendency to settle in specific “sanctuary sites” and lymphatic organs.

- Lymphadenopathy: Painless swelling of lymph nodes, most commonly in the neck (cervical), armpits (axillary), or groin (inguinal).

- Hepatosplenomegaly: Enlargement of the liver and spleen can cause abdominal distension, “fullness” after eating small meals, or a dull ache in the upper quadrants.

- Bone and Joint Pain: Caused by the expansion of the marrow cavity and periosteal involvement. This is particularly common in children, who may present with a limp or refusal to walk.

- CNS Involvement (Leukemic Meningitis): Severe headaches, nausea/vomiting, blurred vision, or cranial nerve palsies (e.g., facial drooping).

- Testicular Enlargement: Usually presents as a painless, firm, unilateral swelling. While rare at initial diagnosis (~2%), it is a classic “sanctuary site” for B-ALL.

Constitutional “B-Symptoms”

These systemic symptoms are caused by the high metabolic demand of the rapidly dividing cancer cells and the release of cytokines.

- Fever: Often occurs without a clear source of infection.

- Night Sweats: Drenching sweats that require changing clothes or bedding.

- Unintentional Weight Loss: Loss of >10% of body weight over a short period.

- Anorexia: Significant loss of appetite.

Pediatric vs. Adult Presentation

| Feature | Pediatric B-ALL | Adult B-ALL |

| Onset | Often acute (days to weeks) | Can be more insidious |

| Bone Pain | Very common (often misdiagnosed as growing pains) | Less prominent |

| WBC Count | Often extremely high at presentation | Variable; often presents with pancytopenia |

| Mediastinal Mass | Rare in B-ALL (more common in T-ALL) | Rare |

“Red Flag” Clinical Scenarios

- The “Limping Child”: Any child with persistent bone pain and a low-grade fever should have a CBC to rule out ALL.

- Superior Vena Cava (SVC) Syndrome: While more common in T-ALL due to a mediastinal mass, a very high blast count in B-ALL can occasionally cause respiratory distress and facial swelling (an emergency).

- Tumor Lysis Syndrome (TLS): At presentation, high-risk patients may already show signs of TLS, such as decreased urine output or muscle cramps, due to high cell turnover.

Prognosis of B-Cell ALL (B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia)

The prognosis of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-cell ALL) has improved significantly in recent years, due to advances in chemotherapy and other treatments. Today, more than 90% of children with B-cell ALL (B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia) are cured, and the overall 5-year survival rate for adults with B-cell ALL (B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia) is about 70%.

However, the prognosis for B-cell ALL (B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia) can vary depending on a number of factors, including:

- Age: Children with B-cell ALL have a better prognosis than adults.

- White blood cell count at diagnosis: Patients with a lower white blood cell count at diagnosis have a better prognosis.

- Central nervous system (CNS) involvement: Patients with CNS involvement have a worse prognosis.

- Minimal residual disease (MRD): Patients with MRD after treatment have a worse prognosis.

- Genetic factors: Some genetic abnormalities, such as the BCR-ABL gene fusion, are associated with a worse prognosis.

Factors that can improve the prognosis for B-cell ALL

There are a number of factors that can improve the prognosis for B-cell ALL (B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia), including:

- Early diagnosis and treatment: Early diagnosis and treatment are essential for a good prognosis.

- Aggressive chemotherapy: Aggressive chemotherapy is the most effective treatment for B-cell ALL (B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia).

- Stem cell transplant: A stem cell transplant can be a curative treatment for B-cell ALL (B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia)in some patients.

- Targeted therapy: Targeted therapies are drugs that target specific molecules that are involved in the growth and development of cancer cells. Targeted therapies can be used to treat B-cell ALL (B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia) in patients who are resistant to chemotherapy or who have relapsed after chemotherapy.

Laboratory Investigations and Diagnosis for B- Cell ALL

Initial Screening

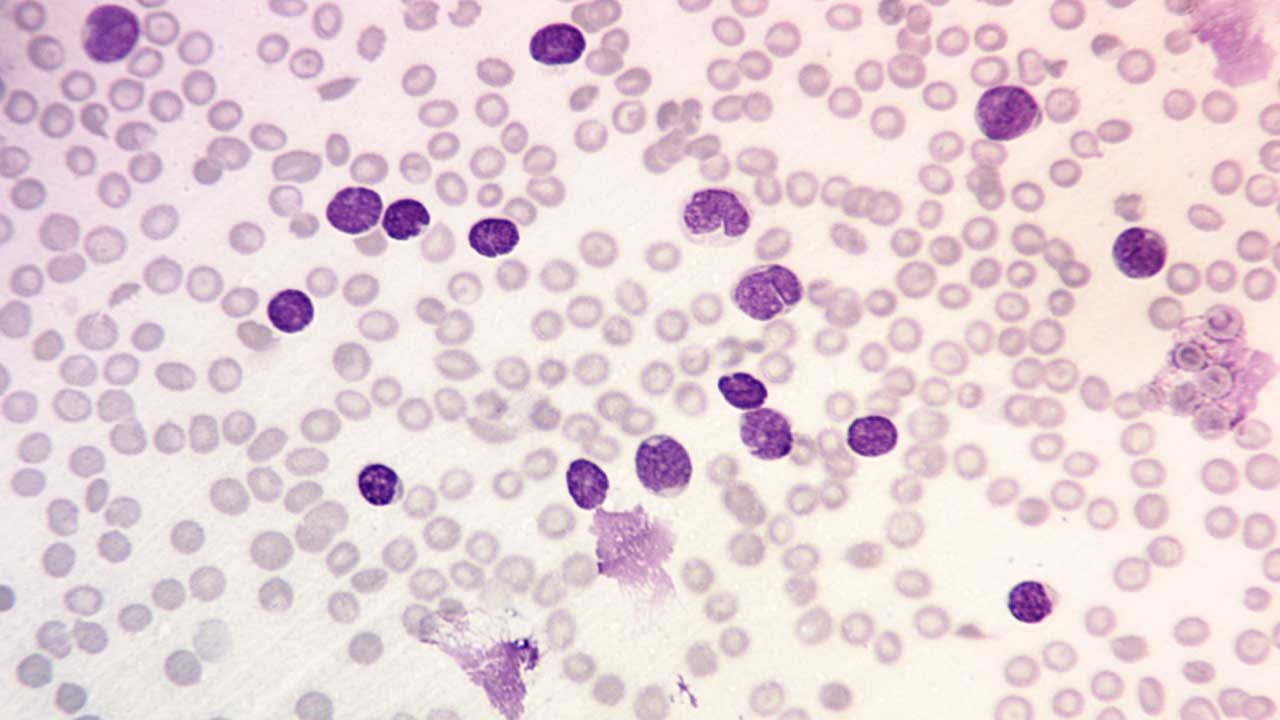

The diagnostic journey usually begins with a Complete Blood Count (CBC) and a peripheral smear.

- CBC Findings: Typically shows pancytopenia (anemia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia). The White Blood Cell (WBC) count is highly variable; it can be low, normal, or extremely high (leukocytosis).

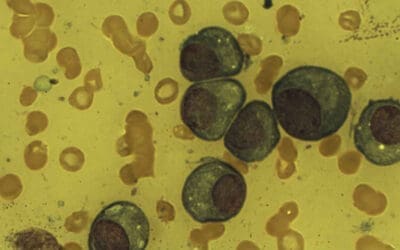

- Peripheral Blood Smear: Characterized by the presence of lymphoblasts. These are usually small to medium-sized cells with:

- High nuclear-to-cytoplasmic (N:C) ratio.

- Fine, “dust-like” chromatin.

- Inconspicuous nucleoli.

- “Hand-mirror” variant: A morphologic subtype where the blast has a cytoplasmic tail (uropod), often seen in B-cell ALL.

- Smudge cells: Fragile leukemic cells that rupture during the smear preparation.

Bone Marrow Examination

A bone marrow aspiration and trephine biopsy are mandatory for a definitive diagnosis.

- Morphology: The marrow is typically hypercellular, packed with a monotonous population of lymphoblasts.

- The 20% Rule: Traditionally, ≥ 20% blasts are required for a diagnosis of leukemia. However, currently, if specific genetic drivers (like KMT2A rearrangements) are present, the diagnosis is often managed as ALL even if the blast count is slightly lower in certain clinical contexts.

- Cytochemistry: B-lymphoblasts are Myeloperoxidase (MPO) negative and Sudan Black B negative, but usually Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) positive (showing a characteristic “chunky” or block-like pattern).

Immunophenotyping (Flow Cytometry)

Flow cytometry is the “gold standard” for determining lineage. B-cell ALL (B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia) cells express markers reflecting their stage of B-cell development.

- Essential B-lineage markers: CD19, CD22, CD79a, and cytoplasmic CD79a.

- Immature markers: TdT (Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase), CD34, and HLA-DR.

- Common ALL Antigen (CALLA): Also known as CD10. Its presence is a key diagnostic and prognostic feature.

- Absence of Lineage Markers: The absence of myeloid (MPO, CD13, CD33) and T-cell markers (CD3, CD7) confirms the B-cell lineage.

Cytogenetics & Molecular Diagnostics

Every new B-ALL case must undergo Karyotyping, FISH, and often Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) for risk stratification.

| Genetic Subtype | Significance |

| t(12;21) [ETV6-RUNX1] | Most common in children; Favorable prognosis. |

| High Hyperdiploidy | >50 chromosomes; Favorable prognosis. |

| t(9;22) [BCR-ABL1] | The Philadelphia chromosome; High risk (requires TKIs like Ponatinib). |

| KMT2A (MLL) rearranged | Common in infants; Very Poor prognosis. |

| Ph-like (BCR-ABL1-like) | Lacks the translocation but has the same “signature”; requires NGS to find JAK or CRLF2 mutations. |

Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) Assessment

Once treatment begins, “remission” is no longer defined just by looking under a microscope. MRD testing is the most powerful predictor of relapse.

- Flow Cytometry-MRD: Detects 1 leukemia cell in 10,000 normal cells.

- NGS-MRD (e.g., ClonoSEQ): Detects 1 leukemia cell in 1,000,000 normal cells. This higher sensitivity is now the preferred standard for deciding if a patient needs a stem cell transplant.

Central Nervous System (CNS) Evaluation

Since the CNS is a “sanctuary site,” a lumbar puncture is required at diagnosis to examine the Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF).

- CSF Cytology: The fluid is centrifuged (Cytospin) and examined for lymphoblasts.

- CNS Involvement: Defined by the presence of blasts and the total WBC count in the fluid (CNS-1, CNS-2, or CNS-3 status).

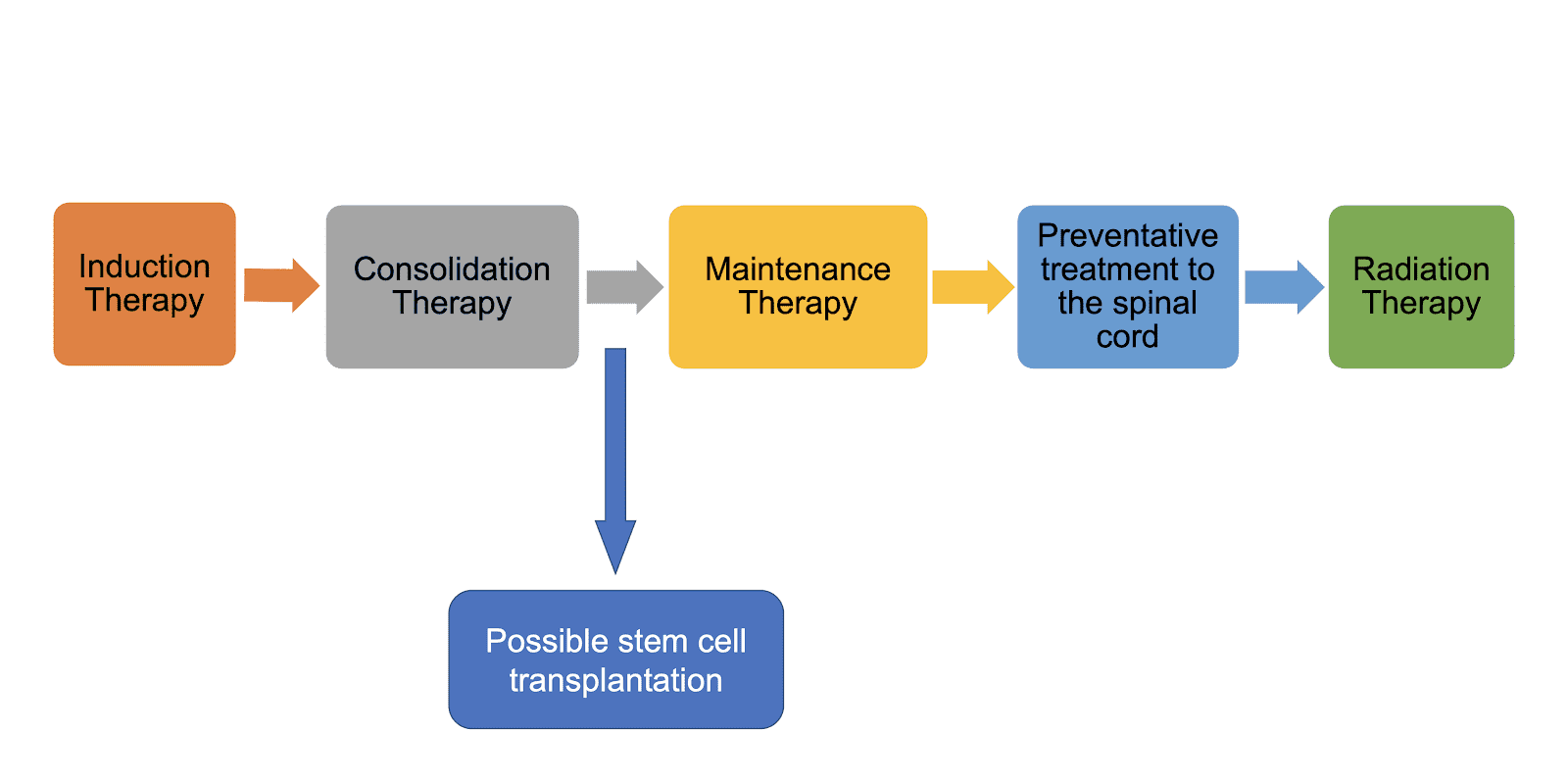

Treatment and Management of B-Cell ALL

The treatment and management of B-cell ALL (B-ALL) is complex and depends on a number of factors, including the patient’s age, overall health, and the stage of the disease. The goal of treatment is to achieve complete remission, which is the absence of detectable leukemia cells in the body.

The treatment can be broken down into three main phases for Philadelphia-negative cases and a separate “Targeted” track for Philadelphia-positive cases.

The Traditional Three-Phase Protocol (Ph-Negative)

For patients without the Philadelphia chromosome, treatment is long (approx. 2–3 years) and follows a structured path.

Phase I: Induction (Remission Induction)

- Goal: To eliminate 99% of visible leukemia cells and achieve “Complete Remission.”

- Standard Regimen: A “Backbone” of Vincristine, Corticosteroids (Dexamethasone/Prednisone), and an Anthracycline (Daunorubicin). Many centers now add Blinatumomab or Rituximab (if CD20+) earlier in the process to improve the depth of remission.

Phase II: Consolidation (Intensification)

- Goal: To destroy “hidden” leukemia cells (Minimal Residual Disease).

- Method: High-dose chemotherapy (Methotrexate, Cytarabine) often cycled with immunotherapy.

- MRD-Guided Decision: If a patient is NGS-MRD positive after consolidation, they are fast-tracked to Stem Cell Transplant or CAR-T therapy.

Phase III: Maintenance

Standard: Low-dose oral chemotherapy (6-Mercaptopurine and Methotrexate) for 2 years.

Goal: To prevent late relapse.

The “Chemo-Free” Revolution (Ph-Positive B-cell ALL)

The treatment for Philadelphia-positive (Ph+) B-cell ALL has been revolutionized by the GIMEMA ALL2820 and PhALLCON trials.

- Frontline Standard: Instead of intensive chemo, patients are increasingly treated with Ponatinib (a 3rd-generation TKI) combined with Blinatumomab (a BiTE). This “Chemo-Free” approach has shown higher molecular response rates and lower toxicity than traditional imatinib-based chemotherapy, allowing many patients (especially older adults) to achieve a cure without a bone marrow transplant.

Immunotherapy & CAR-T (Relapsed/Refractory)

- Blinatumomab (BiTE): A “bridge” molecule that pulls the body’s own T-cells directly onto the CD19-positive leukemia cells.

- Inotuzumab Ozogamicin: An antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) that delivers a toxic “payload” directly into B-cells via the CD22 marker.

- CAR-T Cell Therapy: * Obecabtagene autoleucel (Obe-cel): Approved for adults in late 2024/2025. It is known for its “fast-off” kinetics, which reduces life-threatening side effects like Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS).

- Brexucabtagene autoleucel: Often used for younger adults and high-risk cases.

Supportive Care & Management of Sanctuary Sites

Effective B-cell ALL management involves more than just killing cancer; it requires protecting the rest of the body.

- CNS Prophylaxis: Because chemotherapy doesn’t cross the blood-brain barrier well, Intrathecal (IT) Chemotherapy (Methotrexate/Cytarabine/Steroids) is injected directly into the spinal fluid via lumbar puncture to prevent brain/spinal cord involvement.

- Tumor Lysis Syndrome (TLS): Rapid killing of leukemia cells can release toxic levels of potassium and uric acid into the blood.

- Management: Aggressive hydration and Rasburicase (a recombinant enzyme) are the standard for high-risk patients.

- Growth Factors: G-CSF (Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor) is used to shorten the duration of neutropenia and prevent infections.

B-ALL Management

| Scenario | Primary Management Strategy |

| Newly Diagnosed Adult (Ph-) | Pediatric-inspired Chemo + Blinatumomab |

| Newly Diagnosed Adult (Ph+) | Ponatinib + Blinatumomab (Chemo-free induction) |

| MRD Positive after Consolidation | CAR-T Therapy or Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplant |

| CNS Involvement | Intrathecal Chemotherapy + Cranial Irradiation |

B-ALL vs T-ALL

| Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia | ||

| B-ALL | T-ALL | |

| Incidence | Most common Peak at 3 y.o. Whites, Hispanics, Down syndrome | Peak at 15 y.o. Male:female 3:1 |

| Signs and Symptoms | Fatigue Easy bruising Fever Spread through meninges to CNS | Mediastinal lymphoma (thymus) Cough Shortness of breath Superior vena cava syndrome e.g. swelling of the face |

| Subtypes | t(12;21)(p13;q22)ETV6/RUNX1 Hyperdiploidy Hypodiploidy t(9;22)(q34;q11)BCR/ABL1 t(v;11q23) | |

| Laboratory investigations | FBC: Normochromic, normocytic anemia with thrombocytopenia PBF: Presence of lymphoblasts BMAT: ≥ 20% lymphoblasts Immunophenotyping: + CD19, CD10 – CD45, CD20, CD13, surface light chains | Biopsy: Replacement of thymus or bone marrow tissues with lymphoblasts Immunophenotyping: + CD3, CD5, CD7, HLA-DR – CD34, CD8, CD4, CD19 |

| Prognosis | Excellent: Children Less favorable: Adults | Similar to B-ALL |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Is B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-cell ALL) curable?

Yes, B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) is curable, especially in children. With advancements in treatment, survival rates have significantly improved.

- Children: Have a very high cure rate, often reaching 90% or more.

- Adults: While the outlook is less favorable, survival rates have also increased in recent years.

It’s important to note that treatment involves multiple phases and close monitoring, even after achieving remission. Factors like age, overall health, and specific genetic features of the leukemia can influence treatment outcomes.

Is B-cell ALL (B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia) hereditary?

While there’s a small percentage of cases linked to inherited genetic syndromes, the majority of cases are caused by acquired genetic changes that occur during a person’s lifetime. These changes aren’t passed on to children.

So, while a family history of leukemia might slightly increase your risk, it doesn’t mean you will definitely develop the disease.

What causes B-cell ALL (B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia)?

The exact cause of B-cell ALL (B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia) remains largely unknown. However, researchers believe it’s the result of a combination of factors.

- Genetic Mutations: Changes in the DNA of B cells can disrupt their normal growth and development, leading to uncontrolled proliferation.

- Environmental Factors: While specific factors haven’t been definitively linked, exposure to certain chemicals or radiation might increase the risk.

- Immune System Dysfunction: An overactive or underactive immune system could potentially contribute to the development of B-cell ALL (B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia).

Most cases of B-cell ALL (B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia) occur sporadically and are not inherited. While family history can be a risk factor in some cases, it’s not the primary cause for most individuals.

What is the difference between B-cell ALL and B-cell Lymphoma?

They represent different ends of the same disease spectrum. B-cell ALL primarily involves the bone marrow and peripheral blood, whereas B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma primarily presents as solid masses in the lymph nodes or mediastinum with <25% marrow involvement.

Why is B-cell ALL more curable in children than in adults?

Pediatric B-cell ALL (B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia) more frequently involves favorable genetic mutations (like ETV6-RUNX1 or high hyperdiploidy) and children generally tolerate the intensive multi-year chemotherapy regimens better than older adults, who often have more high-risk mutations like the Philadelphia chromosome.

Can B-cell ALL be detected in a routine blood test (CBC)

A CBC can suggest leukemia if it shows abnormal white cell counts or low hemoglobin/platelets, but a definitive diagnosis requires a bone marrow biopsy and flow cytometry to identify the specific B-cell markers.

What is the significance of the “Sanctuary Sites” in B-cell ALL?

The Central Nervous System (CNS) and the testes are called sanctuary sites because standard systemic chemotherapy does not reach them effectively. Specialized treatments, like intrathecal chemotherapy, are required to prevent relapse in these areas.

Is MRD-negative status the same as being cured?

Being MRD-negative means that current technology cannot detect leukemia cells in the marrow. While this is the best prognostic indicator and suggests a very high chance of long-term remission, patients still require maintenance therapy to ensure the disease does not return.

Glossary of Related Medical Terms

- Alymphocytic Leukemia: A form of leukemia where the total white blood cell count is normal or low, but abnormal blasts are present in the marrow.

- Blast Crisis: A phase in other blood disorders (like CML) that transforms into an acute leukemia like B-ALL.

- Cytogenetics: The study of chromosomal abnormalities (translocations, deletions) within the leukemia cells.

- Extramedullary: Disease located outside the bone marrow, such as in the CNS, skin, or testicles.

- Hypodiploidy: A high-risk genetic state where the leukemia cells have fewer than 44 chromosomes.

- Intrathecal: Administration of chemotherapy directly into the spinal fluid to treat or prevent CNS involvement.

- Lymphoblasts: Immature, non-functional white blood cells that proliferate uncontrollably in ALL.

- Minimal Residual Disease (MRD): The small number of leukemia cells remaining after treatment that are invisible under a microscope but detectable by sensitive lab tests.

- Pancytopenia: A simultaneous decrease in red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets.

- Philadelphia Chromosome: The t(9;22) translocation that creates the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene, a major target for TKIs.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Alaggio R, Amador C, Anagnostopoulos I, Attygalle AD, Araujo IBO, Berti E, Bhagat G, Borges AM, Boyer D, Calaminici M, Chadburn A, Chan JKC, Cheuk W, Chng WJ, Choi JK, Chuang SS, Coupland SE, Czader M, Dave SS, de Jong D, Du MQ, Elenitoba-Johnson KS, Ferry J, Geyer J, Gratzinger D, Guitart J, Gujral S, Harris M, Harrison CJ, Hartmann S, Hochhaus A, Jansen PM, Karube K, Kempf W, Khoury J, Kimura H, Klapper W, Kovach AE, Kumar S, Lazar AJ, Lazzi S, Leoncini L, Leung N, Leventaki V, Li XQ, Lim MS, Liu WP, Louissaint A Jr, Marcogliese A, Medeiros LJ, Michal M, Miranda RN, Mitteldorf C, Montes-Moreno S, Morice W, Nardi V, Naresh KN, Natkunam Y, Ng SB, Oschlies I, Ott G, Parrens M, Pulitzer M, Rajkumar SV, Rawstron AC, Rech K, Rosenwald A, Said J, Sarkozy C, Sayed S, Saygin C, Schuh A, Sewell W, Siebert R, Sohani AR, Tooze R, Traverse-Glehen A, Vega F, Vergier B, Wechalekar AD, Wood B, Xerri L, Xiao W. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Lymphoid Neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022 Jul;36(7):1720-1748. doi: 10.1038/s41375-022-01620-2. Epub 2022 Jun 22. Erratum in: Leukemia. 2023 Sep;37(9):1944-1951. PMID: 35732829; PMCID: PMC9214472.

- Sekeres MA. When Blood Breaks Down: Life Lessons from Leukemia (Mit Press). 2021

- Daniel J. DeAngelo, Elias Jabbour, and Anjali Advani. Recent Advances in Managing Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book 2020 :40, 330-342.

- Yilmaz M, Kantarjian H, Ravandi-Kashani F, Short NJ, Jabbour E. Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adults: current treatments and future perspectives. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2018 Mar;16(3):216-223. PMID: 29742077.

- Saleh K, Fernandez A, Pasquier F. Treatment of Philadelphia Chromosome-Positive Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Adults. Cancers (Basel). 2022 Apr 1;14(7):1805. doi: 10.3390/cancers14071805. PMID: 35406576; PMCID: PMC8997772.

- Huang, F. L., Liao, E. C., Li, C. L., Yen, C. Y., & Yu, S. J. (2020). Pathogenesis of pediatric B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Molecular pathways and disease treatments. Oncology letters, 20(1), 448–454. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2020.11583

- Ashaye, A., Shi, L., Aldoss, I., Montesinos, P., Vachhani, P., Rocha, V., Papayannidis, C., Leonard, J. T., Baer, M. R., Ribera, J. M., McCloskey, J., Wang, J., Gao, S., Rane, D., & Guo, S. (2025). Patient-reported outcomes in Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients treated with ponatinib or imatinib: results from the PhALLCON trial. Leukemia, 39(6), 1342–1350. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-025-02608-4

- Ashaye, A., Ramachandran, N., Quaife, M., Wu, Y., Gutiérrez-Vargas, Á. A., Jiongco, A., Kota, V., Savani, B., & Thomas, C. (2025). Oncologists’ preferences for frontline TKI treatment of Ph+ acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a discrete choice experiment. Future oncology (London, England), 21(25), 3329–3342. https://doi.org/10.1080/14796694.2025.2565497