TL;DR

T-cell ALL, or T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, is an aggressive hematologic malignancy resulting from the clonal expansion of immature T-cell precursors (lymphoblasts) that have failed to differentiate in the thymus.

- Epidemiology: Accounts for approximately 15% of pediatric ALL cases and 25% of adult ALL cases. Unlike the early childhood peak of B-ALL, T-ALL peaks in adolescence and young adulthood (median age ~15 years).

- Causes ▾: Primarily caused by acquired somatic mutations during T-cell development in the thymus; it is not typically hereditary. Over 60% of cases involve activating mutations of the NOTCH1 gene. Other drivers include TAL1, LMO1/2, and TLX1/3 rearrangements.

- Clinical features ▾: Mediastinal mass, superior vena cava syndrome, hyperleukocytosis, extramedullary spread

- Diagnosis ▾: Bone marrow or peripheral blood showing ≥ 20% lymphoblasts; confirmed via flow cytometry (cCD3+, CD7+, CD5+ and CD2+). Cytogenetics evaluation for 14q11 (TCR alpha/delta) or 7q34 (TCR beta) translocations and NOTCH1 status.

- Treatment ▾: Chemotherapy, T-cell specific agents, CNS prophylaxis, stem cell transplant

*Click ▾ for more information

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL)

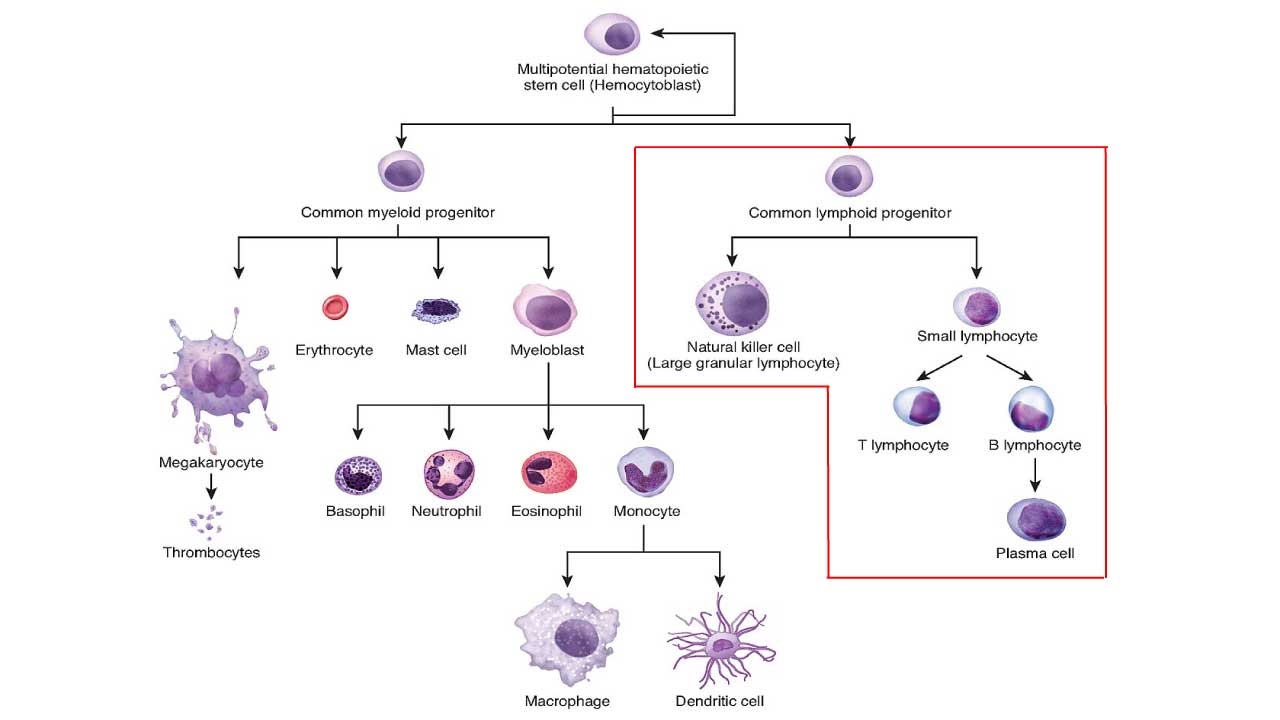

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) which can be divided into B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-cell ALL) and T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-cell ALL), is a type of blood cancer that begins in the bone marrow. The bone marrow is the soft tissue inside the bones where blood cells are made. In ALL, the bone marrow makes too many immature white blood cells called lymphoblasts. Lymphoblasts are a type of lymphocyte, which is a type of white blood cell.

ALL is defined as an aggressive neoplasm of the lymphoid lineage caused by acquired somatic defects due to either inherited factors or infections e.g. viruses in early haematopoietic blasts that impede or significantly impair differentiation leading to accumulation of undifferentiated blasts in the marrow, spilling into the peripheral blood and infiltrate other tissues. Leukemic blasts are too immature to be functional and are prone to suppress or supplant the production of normal haematopoiesis causing pancytopenia.

ALL is the most common type of cancer in children, but it can also occur in adults. It is most common in children under the age of 5 and in adults over the age of 65.

T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-Cell ALL)

T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) is a subtype of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), which is the most common type of cancer in children. T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) is less common than B-cell ALL, but it is still the second most common type of ALL in children. T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) makes up roughly 15% of ALLs.

T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) is caused by the uncontrolled growth of immature T cells. T cells are a type of white blood cell that helps the body fight infection. When T cells become cancerous, they can crowd out healthy blood cells in the bone marrow and bloodstream. This can lead to a number of problems, including fatigue, weakness, and an increased risk of infection.

Epidemiology

The epidemiology of T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) is distinct from its B-cell counterpart, characterized by a unique age distribution, a significant gender gap, and specific ethnic patterns.

Incidence and Proportion of ALL

T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) is less common than B-cell ALL but accounts for a higher percentage of cases in the adult population than in children.

- Pediatric Cases: T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) makes up approximately 12%–15% of all childhood ALL.

- Adult Cases: T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) accounts for about 20%–25% of all adult ALL.

- Subtype Prevalence: ETP-ALL (Early T-cell Precursor) is a critical epidemiological subset, representing roughly 15% of pediatric and up to 35% of adult T-ALL cases.

Age Distribution (The Adolescent Peak)

While B-cell ALL peaks in early childhood (ages 2–5), T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) has a different bimodal distribution.

- Primary Peak: Adolescent years, with a median age of onset around 9 to 15 years.

- Secondary Peak: Young adulthood, with a median age around 30 years.

- Late Adulthood: Unlike B-ALL, the incidence of T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) does not rise as sharply in the elderly population (over 65).

Gender Predominance (The 3:1 Ratio)

One of the most striking epidemiological features of T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) is its heavy male predominance. Males are approximately 3 times more likely to develop T-ALL than females. This gender disparity is consistent across almost all geographic regions and age groups, though the biological reasons (potentially related to X-chromosome tumor suppressor genes) are still under study.

Ethnic and Racial Disparities

Epidemiological studies indicate that T-ALL incidence varies significantly by ancestry.

- African Descent: Individuals of African descent have a notably higher frequency of T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL). In some studies (e.g., South African cohorts), T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) comprises over 30% of all ALL cases, nearly double the global average.

- Hispanic Populations: While B-cell ALL is most common in Hispanic children, T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) also shows a high incidence in this group compared to non-Hispanic whites.

- Asian Populations: Generally reported to have the lowest relative frequency of T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL), often comprising only 7%–10% of childhood ALL cases in East and Southeast Asia.

Survival Trends

Thanks to intensified protocols and the use of T-cell-specific drugs, the “survival gap” between B-ALL and T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) has closed significantly in recent years.

- Pediatric Survival: Long-term survival is now 85%–90% in high-income countries.

- Adult Survival: Remains a challenge at approximately 50%–60%, though it is often superior to the outcomes of “High-Risk” adult B-ALL.

- The ETP-ALL Factor: Historically, ETP-ALL had much lower survival, but data shows that with early stem cell transplantation and BCL-2 inhibitors (Venetoclax), outcomes are beginning to align with standard T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL).

Causes and Risk Factors

While the exact cause of T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) is rarely a single event, it is generally understood as a “multistep oncogenic process.”

Acquired Genetic Mutations (The Primary Cause)

The vast majority of T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) cases are sporadic, meaning they are caused by mutations that occur during a person’s life rather than being inherited. These mutations typically disrupt the normal maturation of T-cells in the thymus.

- NOTCH1 Pathway Activation: This is the “hallmark” of T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL), present in over 60% of cases. Mutations in the NOTCH1 gene (or its regulator FBXW7) lead to the receptor being permanently “turned on,” driving uncontrolled cell growth and survival.

- Transcription Factor Dysregulation: Chromosomal translocations often place potent oncogenes next to T-cell receptor (TCR) enhancers, leading to their overexpression. Key genes include:

- TAL1/SCL: Overexpressed in nearly half of T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) cases.

- TLX1 (HOX11) and TLX3: Often associated with specific age groups and prognostic outcomes.

- LMO1 and LMO2: These “LIM-only” proteins work in concert with TAL1 to arrest T-cell development.

- Cell Cycle Regulators: Deletions in the CDKN2A/B locus (9p21) occur in about 70% of T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) cases. This removes the “brakes” on the cell cycle (p16 and p14), allowing blasts to divide unchecked.

Environmental and External Risk Factors

While less common than genetic drivers, certain exposures are statistically linked to an increased risk of developing ALL.

- Ionizing Radiation: High-dose exposure (e.g., historical nuclear accidents or survivors of atomic bombs) is a well-documented risk factor.

- Prior Chemotherapy/Radiation: Patients treated for previous cancers with Alkylating agents or therapeutic radiation have a slightly higher risk of developing “secondary” or “therapy-related” leukemia.

- Chemical Exposure (Benzene): Chronic exposure to benzene which can be found in cigarette smoke, gasoline, and certain industrial solvents, is a known bone marrow toxin linked to various leukemias.

- Viral Triggers: While rare in the US, the HTLV-1 (Human T-cell Leukemia Virus-1) is a direct cause of a specific T-cell leukemia/lymphoma prevalent in parts of Japan and the Caribbean.

Host Factors and Genetic Syndromes

Certain underlying biological or inherited conditions can predispose an individual to T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL).

- Male Gender: T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) is uniquely notable for its 3:1 male-to-female ratio. The reason for this is not fully understood but may relate to protective effects of certain X-chromosome genes or hormonal influences.

- Inherited Syndromes: Conditions that impair DNA repair or immune function significantly increase leukemia risk:

- Down Syndrome (Trisomy 21)

- Ataxia-telangiectasia (highly associated with T-cell malignancies)

- Li-Fraumeni Syndrome (mutations in TP53)

- Fanconi Anemia and Bloom Syndrome

- The “Delayed Infection” Theory: Similar to B-cell ALL, some researchers suggest that a lack of exposure to common infections in early infancy may lead to a “mis-primed” immune system that overreacts to later triggers, promoting leukemic transformation.

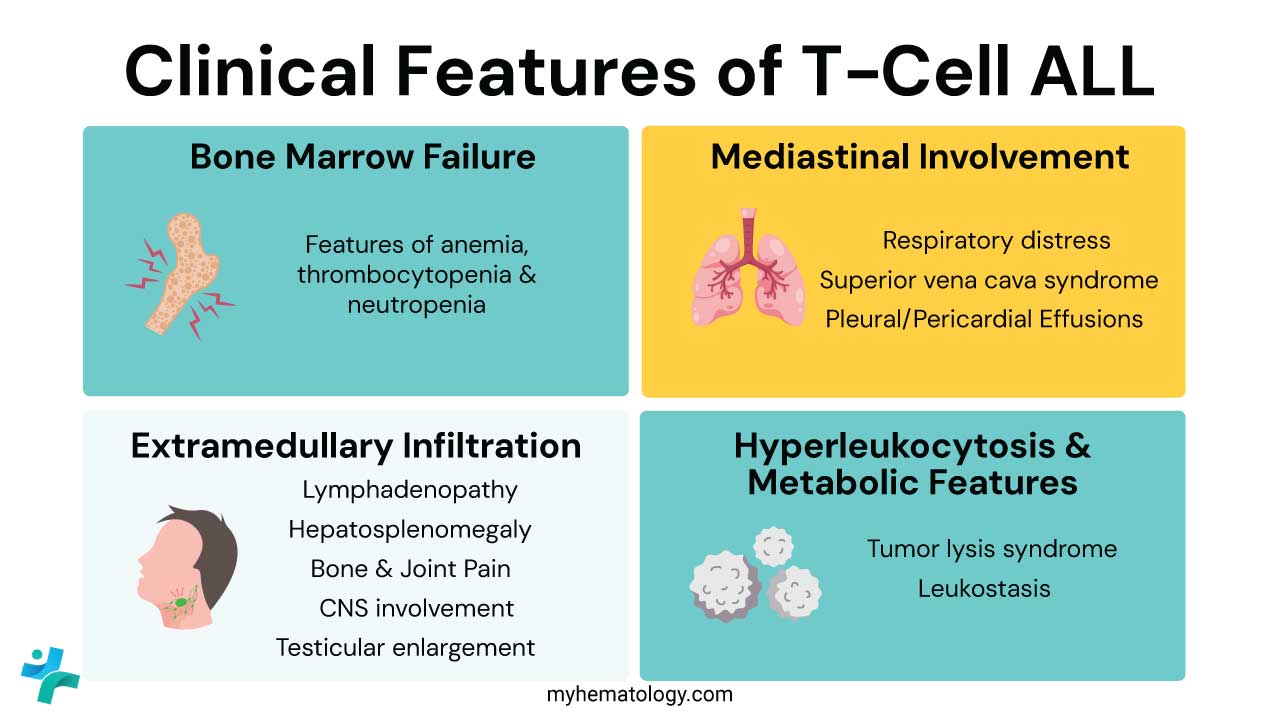

Clinical Features of T-ALL

The clinical features of T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) can be categorized into three pillars: Bone Marrow Failure, Mediastinal Involvement (the hallmark of T-cell ALL), and Extramedullary Infiltration.

Bone Marrow Failure (The “Classic” Triad)

Like other acute leukemias, T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) presents with a rapid replacement of normal hematopoietic cells by lymphoblasts. This manifests as:

- Anemia: Leading to significant fatigue, exertional dyspnea, and pallor.

- Neutropenia: Resulting in recurrent or persistent fevers and severe infections (bacterial, viral, or fungal).

- Thrombocytopenia: Causing mucosal bleeding (gums, nose), petechiae (pinpoint red spots), and easy ecchymosis (bruising).

Mediastinal Involvement (The T-ALL Hallmark)

Up to 75% of T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) patients present with a large, rapidly growing mediastinal (thymic) mass. This is much more common in T-cell ALL than B-ALL and can lead to specific cardiorespiratory emergencies.

- Respiratory Distress: Compression of the trachea or bronchi causes a persistent cough, wheezing (often misdiagnosed as asthma), and dyspnea.

- Superior Vena Cava (SVC) Syndrome: A medical emergency where the mass compresses the SVC, obstructing blood flow from the upper body.

- Signs: Facial swelling (puffiness), neck vein distention, and redness or cyanosis of the upper extremities.

- Warning: Symptoms often worsen when the patient lies flat (orthopnea).

- Pleural/Pericardial Effusions: Leukemic infiltration or venous obstruction can lead to fluid accumulation around the lungs or heart, further compromising breathing and cardiac output.

Extramedullary Infiltration (Beyond the Marrow)

T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) is notoriously “extramedullary,” meaning the blasts frequently colonize organs outside the bone marrow:

- Organomegaly: Massive splenomegaly and hepatomegaly are common, often presenting as abdominal distension or a feeling of early satiety.

- Generalized Lymphadenopathy: Painless, firm swelling of lymph nodes in the neck (cervical), armpits (axillary), and groin (inguinal).

- Central Nervous System (CNS) Involvement: T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) has a higher affinity for the CNS than B-ALL. Patients may present with:

- Persistent headaches and morning vomiting (signs of increased intracranial pressure).

- Cranial nerve palsies (e.g., facial drooping or double vision).

- Testicular Involvement: While rare at initial diagnosis (approx. 2%), clinicians must check for painless, unilateral testicular enlargement, as it is a known “sanctuary site” for leukemic cells.

- Bone and Joint Pain: Caused by the high pressure of leukemic expansion within the medullary cavity, often leading to a refusal to walk in younger children.

Hyperleukocytosis & Metabolic Features

T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) patients often have much higher White Blood Cell (WBC) counts at diagnosis than B-ALL patients (often >100,000/µL):

Tumor Lysis Syndrome (TLS): Due to high cell turnover, patients may present with acute kidney injury and electrolyte imbalances (high potassium, high phosphate, low calcium) even before starting chemotherapy.

Leukostasis: Extremely high blast counts can make the blood “sludge,” leading to hypoxia, visual changes, or neurological confusion.

Clinical Red Flags: When to Suspect T-ALL

In a clinical setting, T-ALL is often a “great masquerader.” Medical students should look for these specific “Red Flags” that point toward T-cell lineage rather than B-cell:

- 🚩 The “Asthma” That Isn’t: A teenager presenting with a new-onset, persistent cough or wheezing that doesn’t respond to bronchodilators. This is often a mediastinal mass compressing the airway.

- 🚩 Facial Fullness: Swelling of the face or neck (often mistaken for an allergic reaction or mumps) which may actually be Superior Vena Cava (SVC) Syndrome.

- 🚩 The “Hyper-Leukocytic” Smear: A White Blood Cell (WBC) count frequently exceeding 100,000/µL, which is significantly higher than the typical B-ALL presentation.

- 🚩 Orthopnea: A patient who becomes severely short of breath specifically when lying flat; this suggests a large chest mass shifting and compressing the heart or lungs.

- 🚩 Rapid Organomegaly: Noticeable, fast-growing enlargement of the liver and spleen, often accompanied by “bulky” lymphadenopathy.

Laboratory Investigations and Diagnosis

Diagnosis of T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) requires a multi-modal approach.

Initial Blood Work (The Screening Phase)

Complete Blood Count (CBC): Usually reveals marked leukocytosis (often >100,000/µL), accompanied by normocytic anemia and significant thrombocytopenia.

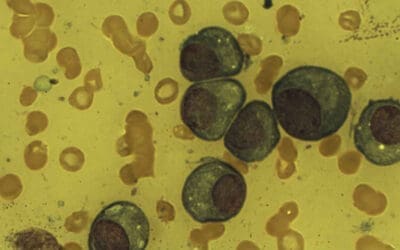

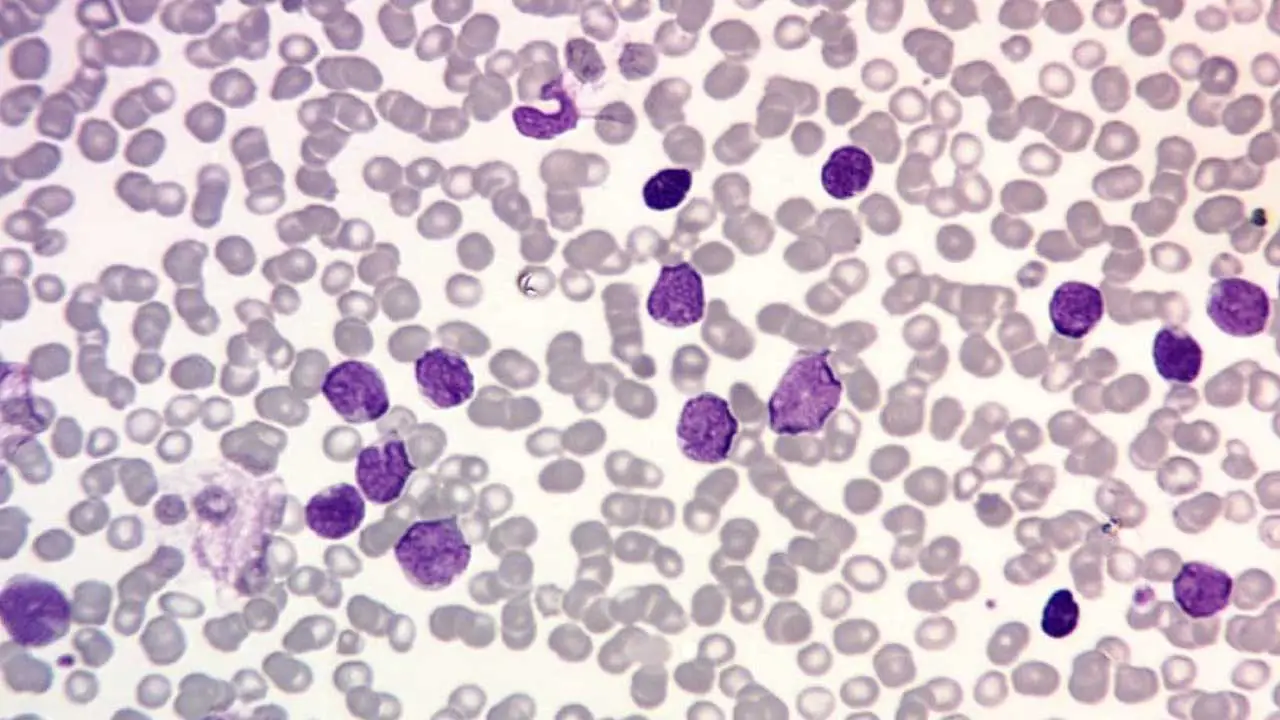

Peripheral Blood Smear: Vital for visualizing lymphoblasts. T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) blasts often have a “convoluted” or indented nuclear shape, dense chromatin, and scant, non-granular cytoplasm. Unlike AML, Auer rods are never present.

Metabolic Panel: Checks for Tumor Lysis Syndrome (TLS)

- Hyperuricemia (high uric acid)

- Hyperphosphatemia (high phosphate)

- Hyperkalemia (high potassium)

- Elevated Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH).

Bone Marrow Aspiration and Biopsy

The gold standard. A diagnosis of T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) is confirmed if there are ≥ 20% lymphoblasts in the marrow. Traditionally, lymphoblasts are Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) positive (chunky pattern) and Myeloperoxidase (MPO) negative.

Flow Cytometry

This is the most critical tool for distinguishing T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) from B-cell ALL or AML.

- Essential T-Lineage Marker: Cytoplasmic CD3 (cCD3) is the most specific.

- Pan-T Markers: CD7 (usually the first to appear), CD5, and CD2.

- Maturity Markers: CD1a, CD4, and CD8 are used to sub-classify T-ALL (Pro-T, Pre-T, Cortical, or Mature).

- The ETP-ALL Signature: A high-risk subtype identified by:

- Positive: CD7

- Weak/Negative: CD5 (<75% of blasts)

- Negative: CD1a and CD8

- Myeloid/Stem Cell Markers: Presence of CD34, CD13, CD33, or CD117.

Essential T-ALL Antigen Markers

| Marker | Significance |

| cCD3 | Most specific marker for T-lineage. |

| CD7 | Usually the first T-cell marker to appear; very sensitive. |

| CD1a | Marker of the Cortical (intermediate) stage; usually favorable. |

| CD34 | Marker of “stemness” or immaturity; found in ETP-ALL. |

Cytogenetics and Molecular Profiling

- Karyotyping & FISH: Used to find translocations involving the T-cell Receptor (TCR) loci:

- 14q11 (TCR alpha/delta locus)

- 7q34 (TCR beta locus)

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS):

- NOTCH1/FBXW7 mutations: Present in >60% of cases (often favorable for initial response).

- Transcription Factor Dysregulation: TAL1, TLX1, or TLX3 rearrangements.

- JAK/STAT Pathway: Mutations often found in the ETP-ALL subtype.

Assessing Extramedullary Involvement

- Lumbar Puncture (LP): Mandatory to evaluate the Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) for leukemic cells, even if neurological symptoms are absent.

- Imaging:

- Chest X-ray/CT: Essential to assess for a mediastinal mass and potential airway compression.

- Abdominal Ultrasound/CT: To document the degree of hepatosplenomegaly.

Key Subtypes of T-Cell ALL

| Subtype Category | Key Feature | Prognostic Impact |

| ETP-ALL (Early T-cell Precursor) | Stem cell/myeloid markers | High Risk (Chemo-resistant) |

| Cortical T-ALL | CD1a positive | Favorable |

| TAL1+ | Most common driver | Standard/Favorable |

| HOXA+ / KMT2Ar | Myeloid-like genetics | Poor/High Risk |

Diagnostic Summary Table

| Investigation | Key Finding in T-Cell ALL |

| Morphology | ≥ 20% Blasts (convoluted nuclei, no Auer rods) |

| Flow Cytometry | cCD3(+), CD7(+), CD5(+), CD2(+) |

| Genetics | NOTCH1 mutations, TCR rearrangements |

| Imaging | Mediastinal mass (anterior compartment) |

| CNS Status | Evaluated via CSF cytology (Lumbar Puncture) |

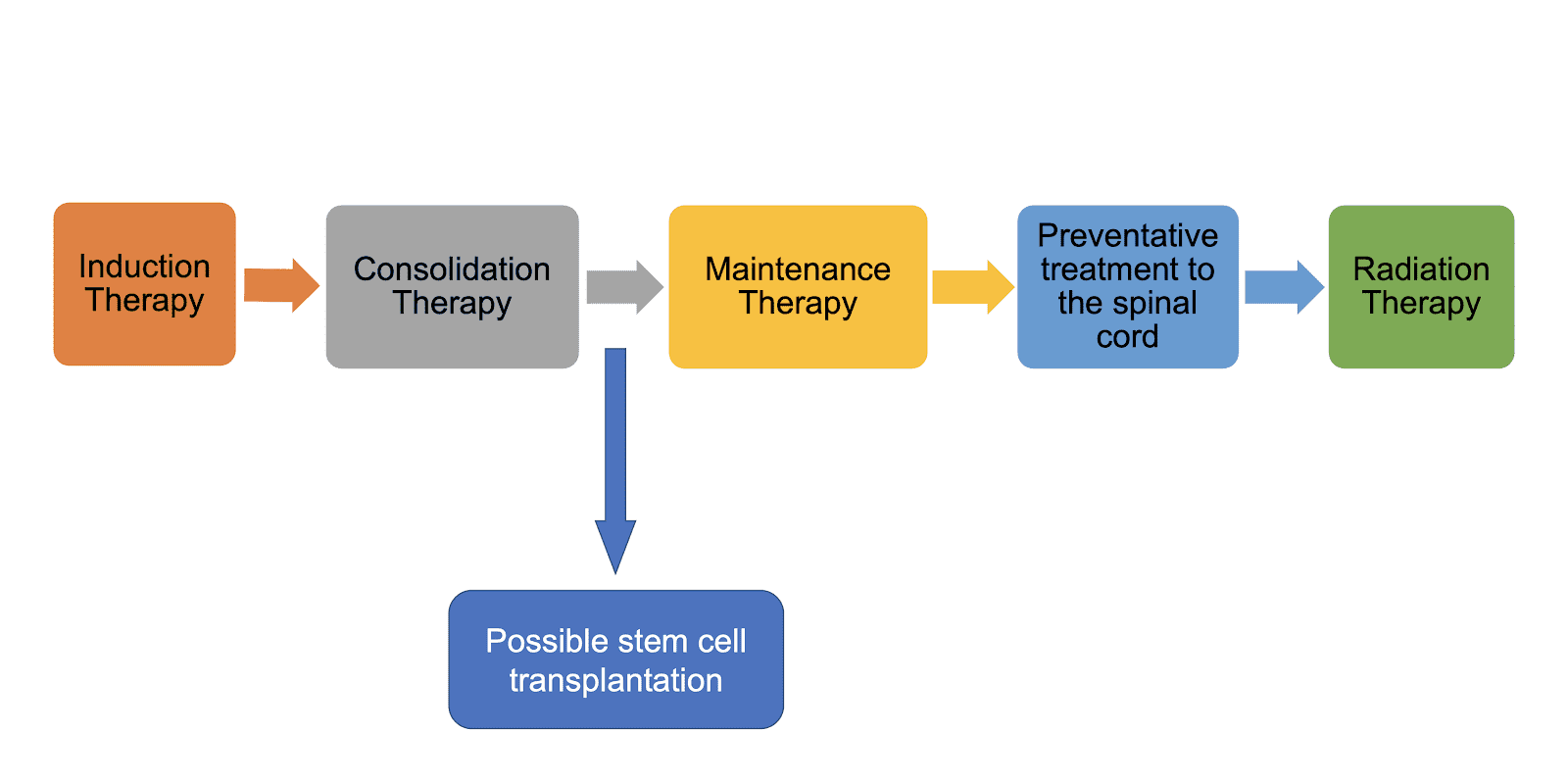

Treatment and Management of T-Cell ALL

The management of T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) has evolved into a highly specialized protocol that balances intensive chemotherapy with newer, T-cell-specific targeted agents.

The treatment is typically divided into four major phases, with additional urgent management for common T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) complications.

Management of Oncologic Emergencies

Because T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) often presents with a high tumor burden, the first 24–48 hours are critical.

- Tumor Lysis Syndrome (TLS) Prophylaxis: Aggressive IV hydration and Rasburicase (recombinant uric oxidase) are standard to prevent acute kidney injury.

- Mediastinal Mass & SVC Syndrome: If the patient has airway compromise or facial swelling:

- Urgent Corticosteroids: High-dose dexamethasone is initiated immediately to shrink the thymic mass.

- Avoidance of Supine Position: Patients are kept upright to prevent airway collapse.

- General anesthesia is extremely risky in these patients due to potential total airway obstruction.

Induction Phase (Achieving Remission)

The goal is a Complete Remission (CR), defined as <5% blasts in the bone marrow.

- Chemotherapy Backbone: Intensive 4- or 5-drug regimens (e.g., Hyper-CVAD or pediatric-inspired BFM protocols).

- Standard drugs: Vincristine, Corticosteroids (Dexamethasone), Anthracycline (Doxorubicin/Daunorubicin), and Pegaspargase. Nelarabine is now increasingly integrated into frontline therapy for patients with high-risk features or those who are slow to respond to initial chemo.

Consolidation & CNS Prophylaxis

Once in remission, intensive treatment continues to eliminate “hidden” leukemia cells.

- Intensification: High-dose Methotrexate and Cytarabine (Ara-C) are used to penetrate “sanctuary sites.”

- CNS Protection: T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-cell ALL) has a high risk of spreading to the brain. All patients receive Intrathecal Chemotherapy (methotrexate/cytarabine injected into the spinal fluid). Cranial radiation is now reserved only for those with proven CNS disease at diagnosis.

- MRD Monitoring: Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) is measured via NGS or Flow Cytometry. If a patient remains “MRD positive” after induction, they are fast-tracked to a stem cell transplant.

Maintenance & Novel Therapies

- Maintenance Phase: A lower-intensity, “backbone” therapy (daily 6-Mercaptopurine and weekly Methotrexate) that lasts 2 to 3 years to prevent late relapse.

- Venetoclax (BCL-2 Inhibitor): Often combined with Navitoclax for Early T-cell Precursor (ETP-ALL), which is historically resistant to standard chemo.

- Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplant (SCT): The definitive “cure” for high-risk T-ALL. It is indicated for:

- ETP-ALL subtype.

- Persistent MRD positivity.

- Any relapsed disease that achieves a second remission.

Summary of Key T-Cell ALL Drugs

| Drug Class | Example | Role in T-Cell ALL |

| Purine Analog | Nelarabine | Specific T-cell cytotoxin; used in high-risk/relapse. |

| BCL-2 Inhibitor | Venetoclax | Targets survival pathways in ETP-ALL. |

| Enzyme | Pegaspargase | Depletes asparagine; T-blasts are uniquely sensitive. |

| Supportive | Rasburicase | Rapidly lowers uric acid in Tumor Lysis Syndrome. |

Summary of B-cell ALL vs T-cell ALL

| Feature | B-cell ALL | T-cell ALL |

| Peak Age | Early childhood (2–5 years) | Adolescents & Young Adults (median 15) |

| Gender | Slight male predilection | Strong male predominance (~3:1) |

| WBC Count | Often normal or low | Characteristically high ($>100k$) |

| Mediastinal Mass | Rare (<10%) | Common (~75%) |

| CNS Involvement | Less common at diagnosis | More common (~10%) |

| Key Markers | CD19, CD20, CD22, CD10 | cCD3, CD7, CD5, CD2 |

| Common Genetics | $t(12;21)$, $t(9;22)$, Hyperdiploidy | NOTCH1 mutations, TCR rearrangements |

| Aggressiveness | Standard to High | Generally Very Aggressive |

| Unique Drugs | Blinatumomab, Inotuzumab | Nelarabine, Venetoclax (for ETP-ALL) |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Is T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) leukemia curable?

Yes, T-cell ALL (T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia) is curable, especially in children.

While it’s a serious condition, advancements in treatment have significantly improved survival rates. Factors like age, overall health, and specific treatment plan influence the outcome.

- Children: Have a higher chance of cure, with survival rates often exceeding 85%.

- Adults: The outlook is less optimistic, with survival rates generally below 50%. However, ongoing research and improved treatments are improving outcomes for adults as well.

Treatment involves a combination of chemotherapy, sometimes radiation therapy, and potentially bone marrow transplantation. Early detection and aggressive treatment are key factors in achieving a positive outcome.

Why is chemotherapy used for T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia?

Chemotherapy is the primary treatment for T-cell ALL because:

- Rapid cell division: Leukemia cells, including T-cell ALL cells, divide rapidly to produce new cancer cells. Chemotherapy drugs are designed to target and kill rapidly dividing cells.

- Systemic disease: T-cell ALL is a systemic disease, meaning it can spread throughout the body. Chemotherapy drugs can reach cancer cells in various locations.

- Induction of remission: The goal of initial chemotherapy (induction phase) is to achieve remission, which means no detectable leukemia cells in the bone marrow.

Key points to remember

- Combination therapy: Multiple chemotherapy drugs are often used together to increase effectiveness and reduce the risk of cancer cells developing resistance.

- Intrathecal chemotherapy: Since T-cell ALL cells can spread to the central nervous system, chemotherapy is often administered directly into the spinal fluid as a preventive measure.

- Side effects: While chemotherapy is effective, it also affects healthy cells, leading to side effects like hair loss, nausea, and fatigue.

Additional treatments

- Stem cell transplantation: This might be considered for patients who don’t respond to chemotherapy or relapse.

- Targeted therapy: Newer treatments focus on specific molecular targets within leukemia cells.

Is T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia aggressive?

Yes, T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-cell ALL) is generally considered more aggressive than B-cell ALL.

This means that T-cell ALL tends to progress faster and may be more difficult to treat. However, advancements in treatment have significantly improved outcomes for both children and adults with T-cell ALL.

Why does T-cell ALL often present with breathing difficulties?

Unlike B-cell ALL, T-cell ALL frequently involves the thymus (located in the chest). As the immature T-cells proliferate, they form a mediastinal mass that can compress the trachea (windpipe) or the Superior Vena Cava, causing cough, shortness of breath, and facial swelling.

What makes ETP-ALL different from standard T-cell ALL?

Early T-cell Precursor (ETP) ALL is a high-risk subtype. It originates from cells that still have some “myeloid” (bone marrow-like) features. It is generally more resistant to traditional chemotherapy and often requires early consideration for stem cell transplantation.

Can T-cell ALL spread to the brain (CNS)?

Yes. T-cell ALL has a higher propensity for Central Nervous System (CNS) involvement than B-cell ALL. For this reason, all T-cell ALL treatment protocols include intensive CNS-directed therapy, such as intrathecal chemotherapy.

Is the Philadelphia chromosome found in T-cell ALL?

Very rarely. While the Philadelphia chromosome (t(9;22)) is common in B-cell ALL, it is almost never seen in T-cell ALL. Genetic drivers in T-cell ALL are more likely to involve NOTCH1, TAL1, or TLX1/3 mutations.

How do survival rates for T-cell ALL compare to B-cell ALL?

Historically, T-cell ALL was considered to have a much worse prognosis. However, with modern intensive chemotherapy backbones and the use of drugs like Nelarabine, survival rates for children with T-cell ALL now approach those of B-cell ALL (over 85-90%).

Glossary of Related Medical Terms

- Cytoplasmic CD3 (cCD3): The most specific lineage marker for T-cells. Unlike surface CD3, cCD3 appears very early in T-cell development, making it the “gold standard” for identifying T-lineage leukemia via flow cytometry.

- Mediastinal Mass: A tumor in the central chest cavity, typically involving the thymus in T-ALL. It is a hallmark feature present in ~75% of cases and can lead to cardiorespiratory emergencies.

- Superior Vena Cava (SVC) Syndrome: A medical emergency caused by the compression of the SVC (usually by a mediastinal mass), leading to facial edema, neck vein distention, and potential airway obstruction.

- Early T-cell Precursor (ETP-ALL): A high-risk immunophenotypic subtype of T-ALL (CD1a-, CD8-, CD5weak) that retains myeloid-associated markers and is often resistant to standard induction chemotherapy.

- NOTCH1 Mutation: An activating genetic mutation found in >60% of T-ALL cases. It drives the constitutive activation of growth pathways and is a major area of research for targeted “gamma-secretase inhibitor” therapies.

- Fratricide: A phenomenon in CAR T-cell therapy where engineered T-cells attack and kill each other because they all express the same target antigen (e.g., CD7). This is a major hurdle in treating T-cell malignancies with immunotherapy.

- Leukostasis: A condition where an extremely high white blood cell count (Hyperleukocytosis) causes increased blood viscosity, leading to “sludging” in small vessels, hypoxia, and organ dysfunction.

- Nelarabine: A purine nucleoside analog prodrug that is uniquely cytotoxic to T-lymphoblasts. It is the only FDA-approved chemotherapy agent specifically indicated for relapsed or refractory T-cell ALL.

- Intrathecal Chemotherapy: The administration of chemotherapy (e.g., methotrexate or cytarabine) directly into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) via lumbar puncture to prevent or treat Central Nervous System (CNS) leukemia.

- Minimal Residual Disease (MRD): The presence of sub-clinical levels of leukemia cells (detectable at 10-4 to 10-6 sensitivity) following treatment. In T-ALL, MRD status is the single most important predictor of relapse and the need for a stem cell transplant.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Alaggio R, Amador C, Anagnostopoulos I, Attygalle AD, Araujo IBO, Berti E, Bhagat G, Borges AM, Boyer D, Calaminici M, Chadburn A, Chan JKC, Cheuk W, Chng WJ, Choi JK, Chuang SS, Coupland SE, Czader M, Dave SS, de Jong D, Du MQ, Elenitoba-Johnson KS, Ferry J, Geyer J, Gratzinger D, Guitart J, Gujral S, Harris M, Harrison CJ, Hartmann S, Hochhaus A, Jansen PM, Karube K, Kempf W, Khoury J, Kimura H, Klapper W, Kovach AE, Kumar S, Lazar AJ, Lazzi S, Leoncini L, Leung N, Leventaki V, Li XQ, Lim MS, Liu WP, Louissaint A Jr, Marcogliese A, Medeiros LJ, Michal M, Miranda RN, Mitteldorf C, Montes-Moreno S, Morice W, Nardi V, Naresh KN, Natkunam Y, Ng SB, Oschlies I, Ott G, Parrens M, Pulitzer M, Rajkumar SV, Rawstron AC, Rech K, Rosenwald A, Said J, Sarkozy C, Sayed S, Saygin C, Schuh A, Sewell W, Siebert R, Sohani AR, Tooze R, Traverse-Glehen A, Vega F, Vergier B, Wechalekar AD, Wood B, Xerri L, Xiao W. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Lymphoid Neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022 Jul;36(7):1720-1748. doi: 10.1038/s41375-022-01620-2. Epub 2022 Jun 22. Erratum in: Leukemia. 2023 Sep;37(9):1944-1951. PMID: 35732829; PMCID: PMC9214472.

- Sekeres MA. When Blood Breaks Down: Life Lessons from Leukemia (Mit Press). 2021

- Daniel J. DeAngelo, Elias Jabbour, and Anjali Advani. Recent Advances in Managing Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book 2020 :40, 330-342.

- Hefazi M, Litzow MR. Recent Advances in the Biology and Treatment of T Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2018 Aug;13(4):265-274. doi: 10.1007/s11899-018-0455-9. PMID: 29948644.

- Caracciolo, D., Mancuso, A., Polerà, N. et al. The emerging scenario of immunotherapy for T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: advances, challenges and future perspectives. Exp Hematol Oncol 12, 5 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40164-022-00368-w

- Fattizzo B, Rosa J, Giannotta JA, Baldini L, Fracchiolla NS. The Physiopathology of T- Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Focus on Molecular Aspects. Front Oncol. 2020 Feb 28;10:273. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00273. PMID: 32185137; PMCID: PMC7059203.

- Raetz EA, Teachey DT. T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2016 Dec 2;2016(1):580-588. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2016.1.580. PMID: 27913532; PMCID: PMC6142501.