Introduction to Hepatomegaly

Hepatomegaly is the medical term for the enlargement of the liver beyond its normal size. It’s important to understand that hepatomegaly itself is not a disease but rather a clinical sign indicating an underlying pathological process affecting the liver or other related systems.

The Liver: A Brief Overview

The liver is a remarkable organ with a vast array of crucial functions essential for life. It acts as the body’s central processing plant, performing hundreds of biochemical reactions simultaneously.

Function of the Liver

Metabolic Functions

Carbohydrate Metabolism

- Gluconeogenesis: Synthesizes glucose from non-carbohydrate sources like amino acids, lactate, and glycerol, helping to maintain blood glucose levels during fasting or starvation.

- Glycogenesis: Converts excess glucose into glycogen for storage in the liver.

- Glycogenolysis: Breaks down stored glycogen into glucose when blood sugar levels drop, releasing it into the bloodstream.

- Insulin Sensitivity: Plays a role in regulating insulin sensitivity and glucose uptake in other tissues.

Protein Metabolism

- Synthesis of Plasma Proteins: Produces the majority of plasma proteins, including albumin (important for maintaining osmotic pressure and transporting various substances), globulins (alpha and beta types, involved in transport and immunity), and clotting factors (essential for blood coagulation, such as fibrinogen, prothrombin, factors V, VII, IX, X).

- Amino Acid Metabolism: Involved in the deamination of amino acids (removal of the amino group), allowing them to be used for energy production or converted into carbohydrates or fats. The toxic ammonia produced during deamination is converted into urea through the urea cycle, which is then excreted by the kidneys.

- Synthesis of Non-Essential Amino Acids: Can synthesize certain amino acids needed by the body.

Lipid Metabolism

- Synthesis of Lipoproteins: Produces various lipoproteins (like VLDL, LDL, HDL) that transport cholesterol, triglycerides, and other lipids in the bloodstream.

- Synthesis of Cholesterol and Triglycerides: Synthesizes cholesterol and triglycerides, which are vital for cell structure and energy storage.

- Fatty Acid Oxidation: Breaks down fatty acids for energy production.

- Bile Acid Synthesis: Synthesizes bile acids from cholesterol, which are crucial for the emulsification and absorption of fats and fat-soluble vitamins in the small intestine.

Detoxification

The liver acts as a major detoxification center, processing and neutralizing a wide range of endogenous (produced within the body, like bilirubin and ammonia) and exogenous (from the environment, like drugs, alcohol, and toxins) substances.

It employs various enzymatic systems (like the cytochrome P450 system) to modify these substances, making them less toxic and more water-soluble for excretion by the kidneys or in bile. Examples include the detoxification of alcohol, metabolic byproducts, and various medications.

Bile Production and Excretion

Hepatocytes continuously produce bile, a complex fluid containing bile acids, bilirubin, cholesterol, phospholipids, water, and electrolytes. Bile is essential for the digestion and absorption of dietary fats and fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) in the small intestine.

Bile also serves as a route for the excretion of certain waste products, including bilirubin (a byproduct of heme breakdown) and excess cholesterol. Bile is stored in the gallbladder and released into the small intestine in response to food intake.

Storage

The liver serves as a significant storage site for various essential substances:

- Glycogen: As mentioned earlier, it stores glucose in the form of glycogen for later release when needed.

- Vitamins: Stores significant amounts of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) and vitamin B12.

- Minerals: Stores iron (bound to ferritin) and copper.

Immune Function

The liver contains specialized immune cells called Kupffer cells, which are resident macrophages within the liver sinusoids. Kupffer cells play a crucial role in the reticuloendothelial system, filtering blood that passes through the liver. They engulf and destroy bacteria, viruses, cellular debris, and other foreign particles, helping to prevent infections and maintain immune homeostasis.

The liver also produces acute phase proteins involved in the inflammatory response.

Hematological Roles

- Synthesis of Clotting Factors: As mentioned under protein metabolism, the liver is the primary site for the synthesis of most coagulation factors necessary for blood clotting.

- Storage of Hematopoietic Factors: Stores vitamin B12 and folic acid, which are essential for red blood cell maturation in the bone marrow. It also plays a role in iron metabolism by storing ferritin and synthesizing transferrin (the iron transport protein).

- Fetal Erythropoiesis: During fetal development, the liver is a major site of red blood cell production (erythropoiesis). This function typically ceases after birth but can be reactivated in adults under certain pathological conditions (extramedullary hematopoiesis).

- Bilirubin Metabolism: The liver processes bilirubin, a yellow pigment produced from the breakdown of heme in aged red blood cells. It conjugates bilirubin, making it water-soluble for excretion in bile.

- Removal of Aged Red Blood Cells: Kupffer cells in the liver also contribute to the removal and breakdown of old or damaged red blood cells.

The liver is a multifaceted organ performing a continuous array of vital functions that are critical for maintaining overall health and homeostasis. Its involvement in metabolism, detoxification, digestion, storage, immunity, and hematology underscores its indispensable role in the body.

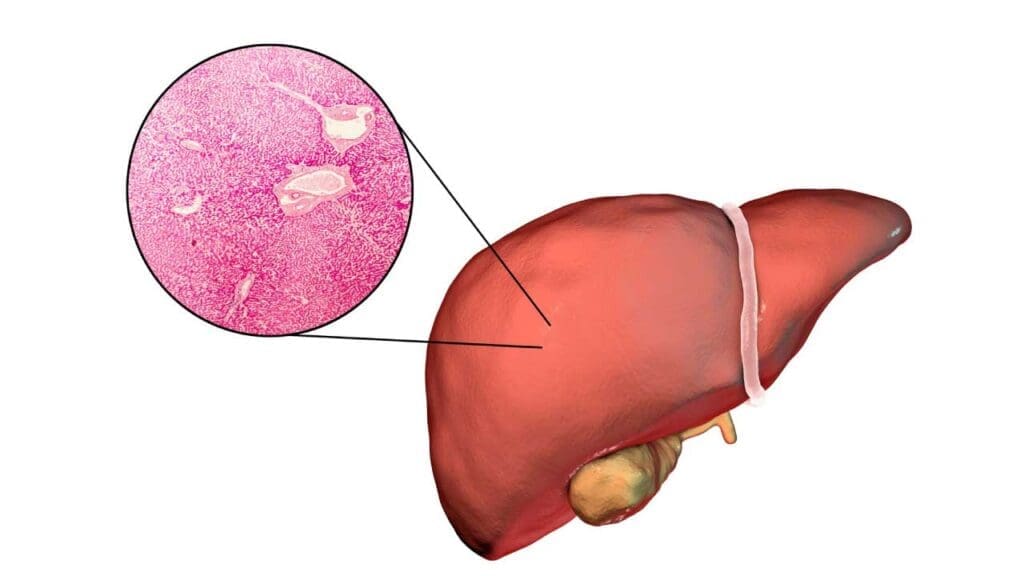

Structure of the Liver

The liver is a large, reddish-brown organ located primarily in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen, beneath the diaphragm. Structurally, it’s composed of four lobes: the large right and left lobes, and the smaller caudate and quadrate lobes. These lobes are further organized into numerous functional units called hepatic lobules.

Each hepatic lobule is roughly hexagonal and centered around a central vein. Radiating outwards from the central vein are plates of liver cells called hepatocytes. Between these hepatocyte plates are specialized capillary-like spaces called sinusoids, lined by endothelial cells and Kupffer cells (resident macrophages).

At the periphery of each lobule are portal triads, containing branches of the hepatic artery (carrying oxygenated blood), the portal vein (carrying nutrient-rich blood from the digestive system), and a bile duct (carrying bile produced by hepatocytes).

Blood from the hepatic artery and portal vein mixes in the sinusoids, allowing hepatocytes to process nutrients, toxins, and synthesize various substances. Processed blood then drains into the central vein, which eventually leads to the hepatic veins and into the inferior vena cava.

Hepatocytes secrete bile into tiny channels called bile canaliculi, which form a network that eventually drains into the bile ducts within the portal triads. These bile ducts merge to form larger ducts, ultimately leading to the common bile duct and the gallbladder for storage.

Location of the Liver

The liver is situated primarily in the right upper quadrant (RUQ) of the abdomen, directly beneath the diaphragm. It extends across the midline into the epigastric region and slightly into the left upper quadrant (LUQ).

Think of it nestled mainly under the right rib cage, providing some protection. It sits superior to organs like the stomach, the right kidney, and the intestines. Its superior surface is convex, fitting snugly against the diaphragm, while its inferior surface is more irregular and related to several other abdominal organs.

Defining Hepatomegaly

Clinical Definition

Clinically, hepatomegaly is defined by the palpation of the liver edge below the right costal margin during a physical examination.

Normally, the lower edge of the liver is just at or slightly below the right rib cage and is often not palpable in healthy adults, except possibly with deep inspiration.

In children, the liver edge may be palpable up to 2 cm below the costal margin and up to 3.5 cm in infants, which can be normal. However, any palpable liver below these age-adjusted limits warrants further investigation.

The clinical assessment also considers the liver span (vertical distance of liver dullness percussed in the midclavicular line), although this is less precise than imaging.

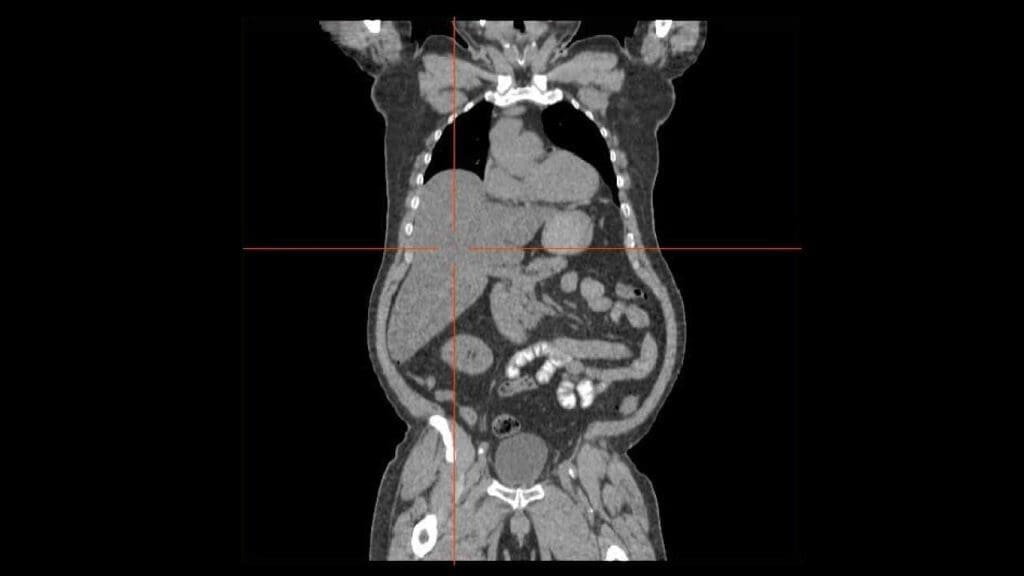

Radiological Definition

Radiologically, hepatomegaly is defined based on liver size measurements obtained through imaging techniques such as ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The specific thresholds can vary slightly depending on the study and the patient’s body habitus, but general guidelines include:

- Ultrasound: A maximum craniocaudal span (vertical measurement) of the right hepatic lobe at the midclavicular line greater than 15.5-16 cm in adults is often considered hepatomegaly. Other measurements, like the diagonal length of the right lobe, can also be used.

- CT and MRI: These modalities can provide more accurate volumetric assessments. A liver volume greater than 2000 mL in adults has been suggested as a threshold for hepatomegaly. Some studies also normalize liver volume to body surface area to provide more individualized assessments.

Degrees of Severity of Hepatomegaly

The degree of hepatomegaly is often described based on the extent to which the liver edge is palpable below the costal margin clinically or by the increase in liver span/volume radiologically. However, the terminology can be somewhat subjective and not always strictly standardized.

Mild Hepatomegaly

- Clinical: Liver edge palpable 1-3 cm below the right costal margin.

- Radiological: Liver span or volume slightly above the upper limit of normal. This may be associated with early stages of various liver diseases like mild fatty liver or resolving hepatitis.

Moderate Hepatomegaly

- Clinical: Liver edge palpable 3-5 cm below the right costal margin.

- Radiological: More significant increase in liver span or volume. This degree can be seen in a wider range of conditions, including chronic liver diseases, more pronounced fatty liver, or certain infiltrative disorders.

Massive (or Gross) Hepatomegaly

- Clinical: Liver edge palpable more than 5 cm below the right costal margin and may extend well into the abdomen. In some definitions, a cephalocaudal length by palpation of ≥ 20 cm is considered massive.

- Radiological: Significantly increased liver span or volume. This is often associated with severe liver disease, advanced metastatic disease, hematological malignancies, or significant congestion due to heart failure.

Causes of Hepatomegaly

Liver Diseases (Hepatobiliary Disorders)

Inflammation (Hepatitis)

- Viral Hepatitis: Acute or chronic infections with hepatitis viruses (A, B, C, D, E), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), Cytomegalovirus (CMV).

- Alcoholic Hepatitis: Liver inflammation due to excessive alcohol consumption.

- Non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH): Inflammation of the liver associated with fatty liver, not related to alcohol.

- Autoimmune Hepatitis: The body’s immune system attacks liver cells.

- Drug-Induced Liver Injury (DILI): Liver damage and inflammation caused by medications or toxins.

Fatty Liver (Steatosis)

- Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD): Accumulation of excess fat in the liver, often associated with obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome.

- Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Fat accumulation due to excessive alcohol intake.

Chronic Liver Diseases and Cirrhosis

Long-term damage to the liver leading to scarring (fibrosis) and eventually cirrhosis from various causes (alcohol, viral hepatitis, NAFLD, autoimmune diseases, etc.). Early cirrhosis might present with hepatomegaly before the liver becomes shrunken in later stages.

Biliary Obstruction

Blockage of the bile ducts, preventing bile flow and leading to liver enlargement. Causes include:

- Gallstones in the common bile duct.

- Tumors of the bile ducts (cholangiocarcinoma) or pancreas compressing the bile ducts.

- Primary Biliary Cholangitis (PBC) and Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis (PSC).

- Biliary atresia (in infants).

Liver Tumors and Cysts

- Benign Tumors: Hemangiomas, adenomas, focal nodular hyperplasia.

- Malignant Tumors:

- Primary Liver Cancer: Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), cholangiocarcinoma, hepatoblastoma (in children).

- Metastatic Liver Disease: Cancer that has spread to the liver from other parts of the body (e.g., colon, lung, breast).

- Liver Cysts: Simple cysts, polycystic liver disease, hydatid cysts (from parasitic infection).

Genetic and Metabolic Disorders

- Hemochromatosis: Iron overload in the liver and other organs.

- Wilson’s Disease: Copper overload in the liver and brain.

- Glycogen Storage Diseases: Genetic disorders affecting the storage and release of glycogen.

- Lysosomal Storage Diseases: Such as Gaucher disease and Niemann-Pick disease, leading to accumulation of specific substances in the liver.

- Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency: Genetic disorder leading to accumulation of abnormal protein in the liver.

- Porphyria: A group of genetic disorders that affect the production of heme.

- Hereditary Fructose Intolerance and Galactosemia: Metabolic disorders affecting sugar metabolism (in children).

Vascular Disorders of the Liver

- Budd-Chiari Syndrome: Blockage of the hepatic veins that drain blood from the liver.

- Sinusoidal Obstruction Syndrome (Veno-occlusive disease): Blockage of small veins in the liver.

- Portal Vein Thrombosis: Blood clot in the portal vein.

- Peliosis Hepatis: Blood-filled cavities within the liver, sometimes drug-induced.

Congestive Causes

- Right-Sided Heart Failure: Back pressure of blood in the systemic circulation leads to congestion and enlargement of the liver. The liver may be pulsatile.

- Constrictive Pericarditis: Inflammation and thickening of the sac surrounding the heart, impairing its ability to fill properly, leading to hepatic congestion.

- Tricuspid Regurgitation: Backflow of blood from the right ventricle to the right atrium and then to the liver, causing congestion.

Infiltrative Diseases

- Amyloidosis: Deposition of abnormal proteins (amyloid) in the liver.

- Sarcoidosis: Formation of granulomas (clumps of inflammatory cells) in the liver and other organs.

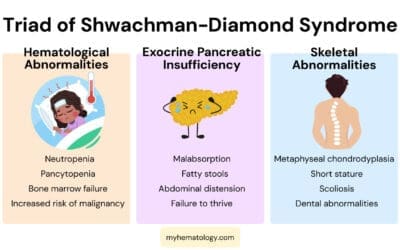

- Myeloproliferative Disorders: Such as myelofibrosis, leading to extramedullary hematopoiesis (blood cell production outside the bone marrow) in the liver.

- Lymphoma and Leukemia: Infiltration of the liver by malignant lymphoid or leukemic cells.

- Systemic Mastocytosis: Accumulation of mast cells in various organs, including the liver.

Infections (Non-Hepatitis)

- Bacterial Infections: Liver abscesses (pyogenic or amebic).

- Parasitic Infections: Malaria, schistosomiasis, hydatid disease.

- Granulomatous Diseases: Tuberculosis.

- Sepsis: Systemic infection can lead to liver enlargement.

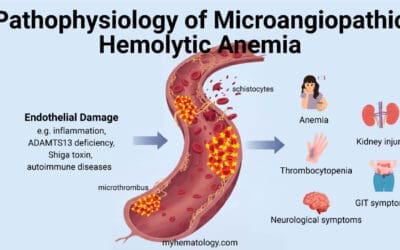

Hematological Disorders

- Hemolytic Anemias: Conditions causing increased destruction of red blood cells, leading to increased bilirubin production and potential liver involvement.

- Sickle Cell Disease and Thalassemia: Chronic anemias that can lead to extramedullary hematopoiesis and liver enlargement.

Other Causes

- Pregnancy: Mild hepatomegaly can occur in some cases of severe preeclampsia or eclampsia.

- Total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN): Prolonged TPN can sometimes lead to fatty liver and hepatomegaly.

- Reye’s Syndrome: A rare but serious condition in children often associated with aspirin use during viral illness.

- Exposure to Toxins: Certain industrial chemicals or environmental toxins can damage the liver.

Clinical Approach to the Patient with Hepatomegaly

A systematic and thorough clinical approach is crucial when evaluating a patient presenting with hepatomegaly. The goal is to identify the underlying cause, assess the severity of liver involvement, and guide appropriate management.

History Taking

A detailed medical history is paramount in narrowing the differential diagnosis. Key areas to explore include:

- Presenting Symptoms

- Right Upper Quadrant (RUQ) pain or discomfort: Characterize the onset, duration, intensity, radiation, and any aggravating or relieving factors.

- Abdominal fullness or distension: May suggest ascites or significant organomegaly.

- Jaundice: Onset, severity, and associated symptoms (dark urine, pale stools, itching).

- Fatigue and malaise: Common in many liver diseases.

- Nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, weight loss: May indicate liver dysfunction or malignancy.

- Fever and chills: Suggestive of infection (e.g., hepatitis, abscess).

- Pruritus (itching): Common in cholestatic conditions.

- Easy bruising or bleeding: May indicate impaired synthesis of clotting factors.

- Changes in mental status: Could suggest hepatic encephalopathy in advanced liver disease.

- Past Medical History

- Known liver diseases: Hepatitis (type and chronicity), cirrhosis, autoimmune liver diseases, genetic liver disorders.

- Cardiac history: Heart failure, pericarditis, valve disease (to assess for congestive hepatomegaly).

- Malignancy: Primary or secondary cancers.

- Autoimmune diseases: Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis, etc.

- Metabolic disorders: Diabetes, hyperlipidemia, obesity.

- Blood transfusions: History of transfusions before routine screening for hepatitis viruses.

- Medication History

- Prescription medications: Pay close attention to drugs known to cause liver injury (DILI).

- Over-the-counter medications: Including NSAIDs, acetaminophen.

- Herbal supplements and traditional medicines: Many can have hepatotoxic effects.

- Social History

- Alcohol consumption: Quantity, frequency, and duration of alcohol intake.

- Intravenous drug use: Risk factor for viral hepatitis.

- Sexual history: Risk factors for viral hepatitis transmission.

- Travel history: Exposure to endemic infections (e.g., viral hepatitis, parasitic diseases).

- Occupation: Exposure to hepatotoxins.

- Dietary history: High-fat diet (NAFLD).

- Family History

- Liver diseases: Cirrhosis, liver cancer, hemochromatosis, Wilson’s disease, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.

- Metabolic disorders: Diabetes, hyperlipidemia.

Physical Examination

A careful and systematic physical examination is crucial to confirm hepatomegaly and look for associated signs of liver disease or systemic illness.

- General Appearance: Assess for jaundice, pallor, cachexia (muscle wasting), edema.

- Vital Signs: Note any fever, tachycardia, or hypotension.

- Abdominal Examination

- Inspection: Look for abdominal distension (ascites), prominent veins (caput medusae suggesting portal hypertension), spider nevi, bruising.

- Auscultation: Listen for bowel sounds and any hepatic bruits (rare, may suggest increased blood flow in tumors or alcoholic hepatitis).

- Percussion

- Liver Span: Percuss the upper and lower borders of liver dullness in the midclavicular line and sometimes the midsternal line. Correlate this with palpated liver edge. Normal adult liver span in the midclavicular line is typically 6-12 cm.

- Ascites: Assess for shifting dullness and fluid wave.

- Splenomegaly: Percuss and palpate for an enlarged spleen, which can be associated with portal hypertension, hematological disorders, and infections.

- Palpation of the Liver

- Technique: Start palpation in the right iliac fossa and move upwards towards the right costal margin during inspiration.

- Liver Size: Estimate the distance the liver edge extends below the costal margin.

- Liver Edge Characteristics: Note whether the edge is smooth or nodular, sharp or blunt, firm or soft, and tender or non-tender.

- A smooth, tender liver suggests acute inflammation or congestion.

- A firm, smooth liver may be seen in chronic hepatitis or early cirrhosis.

- A hard, nodular liver is characteristic of cirrhosis or metastatic disease.

- A pulsatile liver may suggest tricuspid regurgitation or right heart failure.

- Tenderness: Localized tenderness over the liver may indicate acute inflammation, infection, or stretching of the liver capsule.

- Examination for Stigmata of Chronic Liver Disease: Spider nevi, palmar erythema, gynecomastia (in males), testicular atrophy, loss of body hair.

- Cardiovascular Examination: Assess for signs of heart failure (jugular venous distension, peripheral edema, heart murmurs).

- Skin Examination: Look for jaundice, spider nevi, bruising, excoriations (due to itching).

- Neurological Examination: Assess for signs of hepatic encephalopathy (asterixis, confusion).

- Lymph Node Examination: Enlarged lymph nodes may suggest malignancy or infection.

Initial Assessment and Differential Diagnosis

Based on the history and physical examination, formulate a preliminary differential diagnosis.

- Hepatomegaly with Jaundice: Suggests hepatocellular dysfunction or biliary obstruction.

- Hepatomegaly with RUQ Pain and Fever: Raises suspicion for acute hepatitis, cholangitis, or liver abscess.

- Hepatomegaly with Signs of Chronic Liver Disease: Points towards cirrhosis or other chronic liver conditions.

- Hepatomegaly with Signs of Heart Failure: Suggests congestive hepatomegaly.

- Hepatomegaly with Splenomegaly: May indicate portal hypertension, hematological disorders, or infiltrative diseases.

- Massive Hepatomegaly without Prominent Jaundice: Could suggest infiltrative disorders, hematological malignancies, or metastatic disease.

Ordering Initial Investigations

Based on the initial assessment, order appropriate laboratory and imaging studies.

- Liver Function Tests (LFTs):

- Aminotransferases (ALT, AST): Assess hepatocellular injury.

- Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) and Gamma-Glutamyl Transferase (GGT): Assess cholestasis.

- Bilirubin (total and direct): Evaluate for jaundice.

- Albumin and Prothrombin Time (PT)/INR: Assess synthetic liver function.

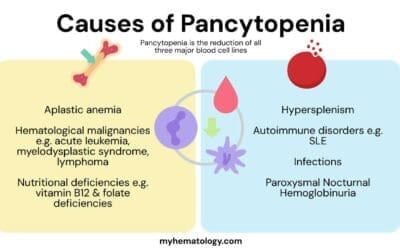

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): To evaluate for anemia, thrombocytopenia, leukocytosis, or atypical cells.

- Renal Function Tests (Creatinine, BUN): To assess overall organ function.

- Coagulation Studies (PT/INR, aPTT): If bleeding is suspected or liver synthetic function is impaired.

- Urinalysis: To assess for bilirubinuria.

- Abdominal Ultrasound: Often the initial imaging modality to assess liver size, echotexture (fatty changes, cirrhosis), identify focal lesions (cysts, tumors), evaluate the biliary tree, and assess for ascites and splenomegaly. Doppler ultrasound can assess hepatic and portal vein blood flow.

Interpreting Initial Results and Further Investigations

The results of the initial investigations will help refine the differential diagnosis and guide further testing.

- Markedly Elevated Aminotransferases: Suggest acute hepatocellular injury (e.g., viral hepatitis, drug-induced liver injury, ischemic hepatitis). Further testing for specific viral serologies, drug history, and possibly autoimmune markers may be indicated.

- Elevated ALP and GGT with Relatively Mild Aminotransferase Elevation: Suggests cholestasis or biliary obstruction. Further imaging with CT or MRI/MRCP may be necessary to visualize the biliary tree.

- Abnormal Synthetic Function (Low Albumin, Prolonged PT/INR): Indicates significant liver dysfunction, often seen in chronic liver disease.

- Abnormal CBC: May suggest infection, anemia of chronic disease, or hematological malignancy.

- Ultrasound Findings: May reveal fatty liver, cirrhosis, masses, cysts, or biliary obstruction.

Considering Advanced Investigations

Depending on the clinical picture and initial results, more specialized investigations may be required.

- Viral Serologies: Hepatitis A, B, C, D, E viruses, EBV, CMV.

- Autoimmune Markers: Antinuclear antibody (ANA), anti-smooth muscle antibody (ASMA), anti-mitochondrial antibody (AMA), liver-kidney microsomal antibody (LKM-1).

- Metabolic Studies: Iron studies (ferritin, transferrin saturation), ceruloplasmin, alpha-1 antitrypsin level.

- Tumor Markers: Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) for HCC, CA 19-9 for cholangiocarcinoma or pancreatic cancer.

- CT Scan or MRI of the Abdomen: Provides more detailed anatomical information and is useful for characterizing liver lesions and assessing for spread of malignancy.

- Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography (MRCP): Non-invasive imaging of the biliary tree.

- Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP): Invasive procedure to visualize and treat biliary obstruction.

- Liver Biopsy: Often the definitive diagnostic tool for many liver diseases, providing histological information on the nature and severity of liver damage, as well as identifying specific causes like autoimmune hepatitis, infiltrative diseases, and staging fibrosis.

Synthesis of Findings and Diagnosis

Integrate all the information gathered from the history, physical examination, laboratory tests, and imaging studies to arrive at a diagnosis. Consider the most likely etiologies based on the clinical context.

Management and Follow-up

Once the underlying cause of hepatomegaly is identified, initiate appropriate treatment. Management will vary greatly depending on the specific diagnosis. Regular monitoring of liver function and liver size may be necessary to assess treatment response and disease progression.

Complications Associated with Underlying Causes of Hepatomegaly

The complications associated with hepatomegaly are not due to the enlarged liver itself, but rather stem from the underlying conditions that cause the liver to enlarge. These complications can be diverse and depend heavily on the specific etiology of the hepatomegaly.

Complications of Liver Diseases (Hepatobiliary Disorders)

Progression to Cirrhosis

Many chronic liver diseases (e.g., chronic viral hepatitis, alcoholic liver disease, NAFLD) can progress to cirrhosis, characterized by irreversible scarring and impaired liver function.

- Portal Hypertension: Increased pressure in the portal vein system, leading to:

- Esophageal and Gastric Varices: Swollen blood vessels in the esophagus and stomach that can rupture and cause life-threatening bleeding.

- Ascites: Accumulation of fluid in the peritoneal cavity.

- Splenomegaly: Enlargement of the spleen due to congestion.

- Hepatic Encephalopathy: Brain dysfunction due to the buildup of toxins that the damaged liver cannot filter.

- Hepatorenal Syndrome: Kidney failure in the setting of advanced liver disease.

- Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis (SBP): Infection of the ascitic fluid.

- Liver Failure (Hepatic Insufficiency): The liver loses its ability to perform its vital functions, leading to jaundice, coagulopathy, hypoalbuminemia, and encephalopathy.

- Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC): Increased risk of developing liver cancer in the setting of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis.

Biliary Obstruction Complications

- Cholangitis: Infection of the bile ducts, a serious and potentially life-threatening condition.

- Jaundice: Persistent buildup of bilirubin, leading to itching and other symptoms.

- Secondary Biliary Cirrhosis: Chronic obstruction can lead to liver damage and cirrhosis.

Liver Tumors (Benign and Malignant)

- Space-Occupying Effects: Large tumors can compress surrounding structures, causing pain or discomfort.

- Rupture and Bleeding: Some tumors, particularly large or vascular ones, can rupture and cause internal bleeding.

- Metastasis (Malignant Tumors): Spread of cancer cells to other parts of the body.

- Paraneoplastic Syndromes: Systemic symptoms caused by substances produced by the tumor cells.

Genetic and Metabolic Disorders

Complications are specific to each disorder (e.g., iron overload in hemochromatosis leading to organ damage, neurological issues in Wilson’s disease).

Complications of Congestive Causes

- Worsening Heart Failure: The underlying heart condition progresses, leading to more severe symptoms and complications.

- Cardiac Cirrhosis: Chronic liver congestion due to heart failure can eventually lead to liver fibrosis and cirrhosis.

Complications of Infiltrative Diseases

- Organ Dysfunction: Infiltration of the liver by abnormal substances (e.g., amyloid, granulomas, malignant cells) can impair its function.

- Systemic Manifestations: Infiltrative diseases often affect other organs as well, leading to a wide range of complications depending on the specific condition (e.g., cardiac involvement in amyloidosis, pulmonary involvement in sarcoidosis).

- Malignancy-Related Complications: Infiltration by lymphoma or leukemia can lead to bone marrow suppression, infections, and other complications of hematological malignancies.

Complications of Infections (Non-Hepatitis)

- Sepsis: Systemic spread of infection from a liver abscess or other infectious focus.

- Rupture of Abscess: A liver abscess can rupture into the peritoneal cavity, leading to peritonitis.

- Chronic Infection and Inflammation: Persistent infections can cause chronic liver damage and fibrosis.

Complications of Hematological Disorders

- Severe Anemia: Due to the underlying blood disorder.

- Increased Risk of Infections: Especially in hematological malignancies.

- Organ Damage from Extramedullary Hematopoiesis: Infiltration of organs like the liver and spleen with blood-forming cells can impair their function.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Goldberg S, Hoffman J. Clinical Hematology Made Ridiculously Simple, 1st Edition: An Incredibly Easy Way to Learn for Medical, Nursing, PA Students, and General Practitioners (MedMaster Medical Books). 2021.

- Askin DF, Diehl-Jones WL. The neonatal liver: Part III: Pathophysiology of liver dysfunction. Neonatal Netw. 2003 May-Jun;22(3):5-15. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.22.3.5. PMID: 12795504.

- Walker WA, Mathis RK. Hepatomegaly. An approach to differential diagnosis. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1975 Nov;22(4):929-42. PMID: 1105367.

- Jensen KK, Oh KY, Patel N, Narasimhan ER, Ku AS, Sohaey R. Fetal Hepatomegaly: Causes and Associations. Radiographics. 2020 Mar-Apr;40(2):589-604. doi: 10.1148/rg.2020190114. PMID: 32125959.