TL;DR

Hodgkin Lymphoma or formerly known as Hodgkin’s disease is a heterogeneous group of disorders caused by malignant lymphocytes that accumulate in lymph nodes presenting as lymphadenopathy. Hodgkin Lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) is differentiated from non-Hodgkin lymphoma by presence of Reed-Sternberg (RS) cells and a strong predisposition to appear within one lymph node group and spread to the next.

- Hodgkin lymphoma signs and symptoms ▾:

- Painless, asymmetrical, firm, discrete and rubbery lymphadenopathy

- Splenomegaly (~50% of cases) but seldom massive

- Fever

- Pruritus

- Alcohol-induced pain

- Hypermetabolism e.g. weight loss, cachexia, anorexia, night sweats

- Laboratory investigations ▾:

- CBC & PBF: Normochromic normocytic anemia, neutrophilia, eosinophilia and lymphopenia

- Lymph node biopsy: Presence of Reed-Sternberg cells

- ↑ ESR, CRP and serum LDH

- Immunophenotyping:

- Classical HL: CD15+, CD30+, CD45-

- Nodular lymphocyte-predominant HL: CD20+, CD15-, CD30-, EBV-

- Positive in situ hybridization (ISH) to EBV-encoded RNA (EBER) or detection of EBV-LMP1 (latent-membrane protein 1) by immunohistochemical staining.

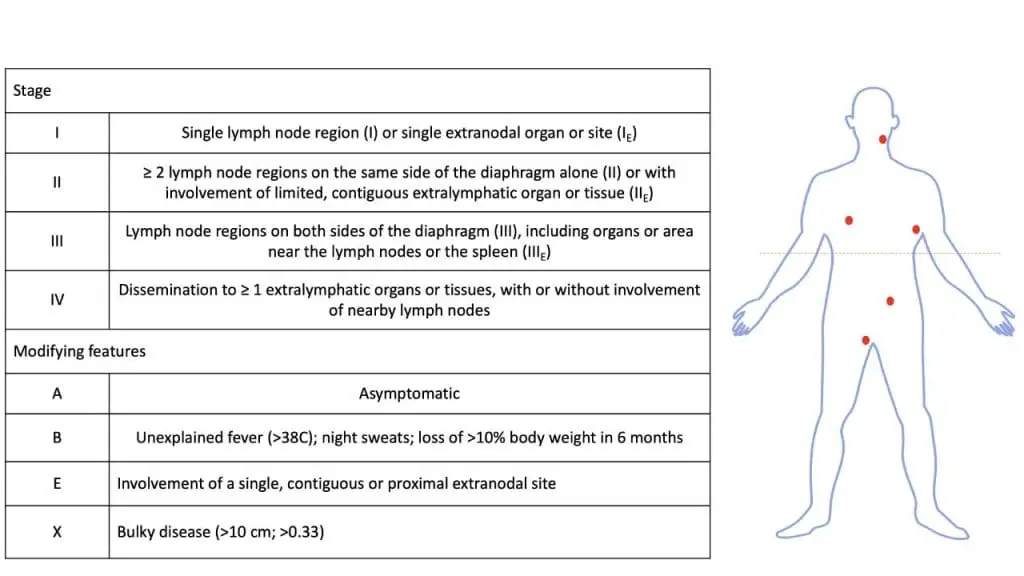

- Clinical staging of Hodgkin Lymphoma (HL) ▾: The current standard staging system is the Lugano classification, which integrates PET-CT findings, while the older Ann Arbor system (with Cotswolds modification) is still relevant.

- Treatment and management ▾: Radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy (combination of adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine and dacarbazine (ABVD)) or allogeneic stem cell transplantation

*Click ▾ for more information

Introduction

Lymphomas are a group of diseases caused by malignant lymphocytes that accumulate in lymph nodes leading to lymphadenopathy. The major subdivision of lymphomas is into Hodgkin lymphoma (presence of Reed-Sternberg cells) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) is distinguished from non-Hodgkin lymphoma by two main features.

- Presence of Reed-Sternberg cells.

- Strong tendency for Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) to arise within a single lymph node group and spread from one lymph node group to the next.

Thus, staging has a greater influence on the treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) than on non-Hodgkin lymphomas.

What are Reed-Sternberg cells?

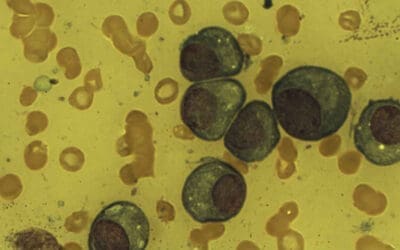

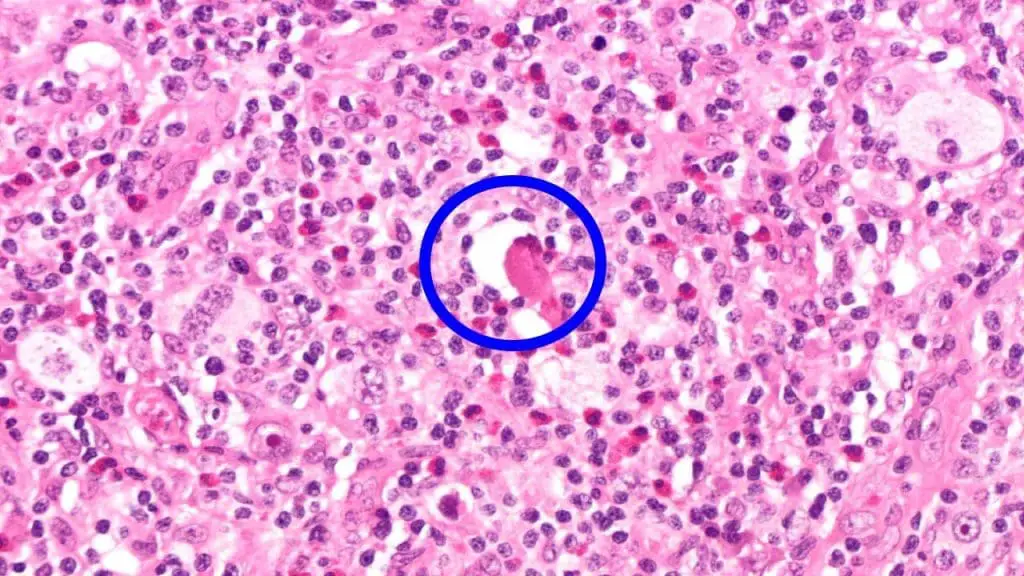

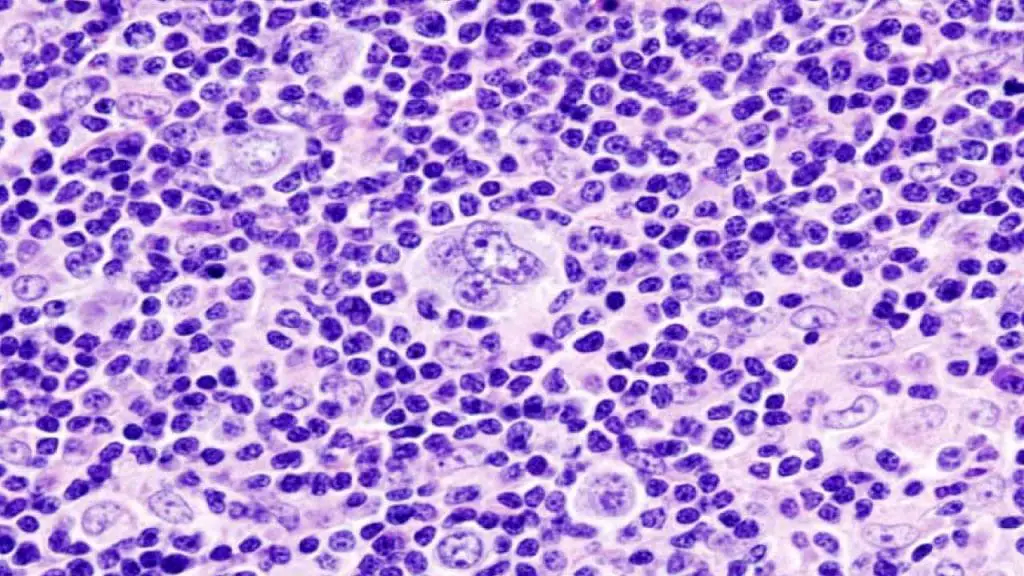

Reed-Sternberg cells are large, abnormal white blood cells that are found in the lymph nodes of people with Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease). The presence of Reed-Sternberg cells are the hallmark of this type of cancer. Reed-Sternberg cells are thought to be derived from B cells, a type of white blood cell that produces antibodies. This B cell has a ‘crippled’ immunoglobulin gene caused by the acquisition of mutations that prevent synthesis of full-length immunoglobulin. They have lost many of the characteristics of B cells and have become cancerous.

Reed-Sternberg cells are typically large and have multiple nuclei. Reed-Sternberg cells may also contain eosinophilic inclusion bodies, which are structures that stain pink with eosin, a type of dye used in histology.

Reed-Sternberg cells can produce a variety of cytokines, which are proteins that communicate with other cells. These cytokines can help to promote the growth and survival of Reed-Sternberg cells and can also suppress the immune system.

What are the different subtypes of Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease)?

The World Health Organization (WHO) divides Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) into two main subtypes. They are the Classic Hodgkin lymphoma and Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma. Classic Hodgkin lymphoma is the more common subtype, accounting for about 90% of cases. Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma is a less common subtype, accounting for about 10% of cases.

Classic Hodgkin Lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease)

Classic Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) has four subtypes.

- Nodular sclerosis is the most common form of Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) in young adults. It is characterized by two pathologic findings.

- The presence of lacunar cells which are variant Reed-Sternberg cells. Their ample cytoplasm tends to retract during formalin fixation so that they are surrounded by empty space.

- The presence of large bands of collagen that are deposited by reactive fibroblasts. This subtype is rarely associated with Epstein-Barr virus.

- Mixed cellularity Hodgkin lymphoma. This subtype is most common in older males where the lymph nodes are composed of a mixture of inflammatory cells and numerous Reed-Sternberg cells with intermediate numbers of lymphocytes. About 70% of cases are associated with EBV.

- Lymphocyte-rich Hodgkin lymphoma. This is not a common subtype with predominantly small lymphocytes. About 40% of cases are associated with EBV.

- Lymphocyte-depleted subtype. This is a rare subtype except in HIV positive patients. There is a dominance of Reed-Sternberg cells with a sparse number of lymphocytes. It is almost always associated with EBV.

Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease)

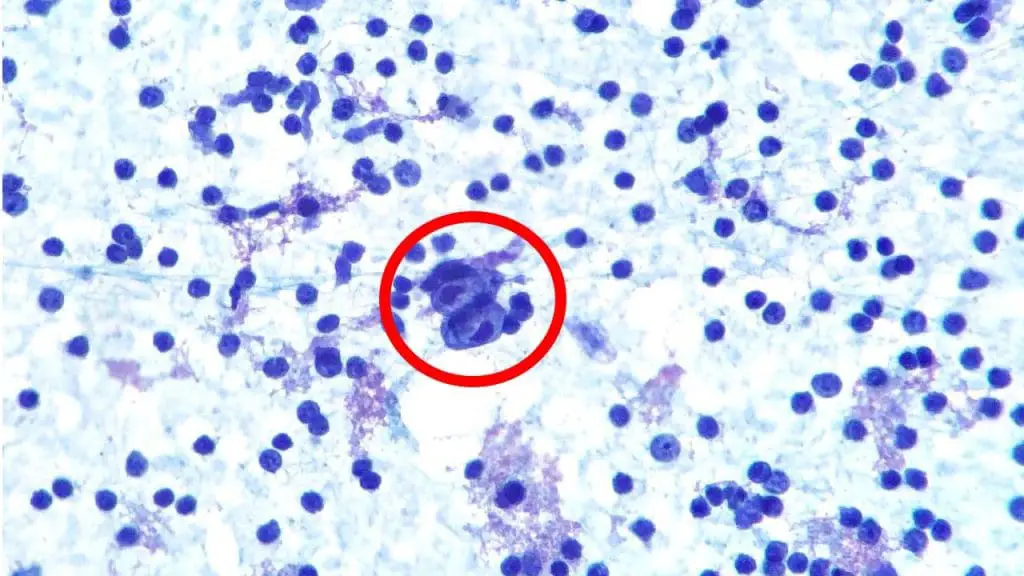

Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma is characterized by the presence of lymphocyte-predominant cells, sometimes termed “popcorn cells,” which are a variant of Reed-Sternberg cells. It is uncommon and found primarily in young to middle-aged males within axillary or cervical lymph nodes. Classic Reed-Sternberg cells are rare or absent.

It is important to know the subtype since it plays a large part in determining the type of treatment the patient will receive.

Summary of Hodgkin Lymphoma (HL) Classifications

| Classification | Characteristics | |||

| Classic Hodgkin Lymphoma | ||||

| Nodular Sclerosis | Most common in young adults Presence of lacunar cells (a variant of Reed-Sternberg cells) Presence of large collagen bands deposited by reactive fibroblasts | |||

| Mixed Cellularity | Most common in older males A combination of inflammatory and Reed-Sternberg cells with lymphocytes ~70% associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) | |||

| Lymphocyte-rich | Predominantly small lymphocytes with scanty Reed-Sternberg cells 40% associated with EBV | |||

| Lymphocyte-depleted | Rare other than in HIV patients PredominantlyReed-Sternberg cells with scanty lymphocytes Almost always associated with EBV | |||

| Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma Uncommon Primarily in young to middle-aged males The tumor cells have nuclei that are lobulated or popcorn-kernel like (a variant of Reed-Sternberg cells) Classic Reed-Sternberg cells are rare or absent | ||||

Hodgkin Lymphoma (Hodgkin’s Disease) Symptoms

Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) is a type of cancer that starts in the lymphatic system. The lymphatic system is a network of vessels and nodes throughout the body that helps to fight infection. Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) is a relatively rare type of cancer, accounting for about 1% of all cancers.

The most common clinical sign of Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) is a painless, asymmetrical enlargement of the lymph nodes in the neck, underarms, or groin (lymphadenopathy). The most common lymph node involvement is the cervical nodes followed by the axillary nodes and then the inguinal nodes. The lymph nodes may be firm, discrete and rubbery to the touch. Clinical splenomegaly occurs during the course of the disease in 50% of patients and is seldom massive.

Other common symptoms include:

- Fever

- Pruritus / itching

- Alcohol-induced pain in the areas where disease is present

- Hypermetabolism Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) symptoms

- Weight loss

- Night sweating

- Anorexia

- Cachexia

Less common Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) symptoms and signs may include:

- Bone pain

- Headache

- Skin rash

- Jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes)

- Peripheral neuropathy (numbness and tingling in the hands and feet)

How is Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) diagnosed?

Lymph Node Biopsy: The Gold Standard

Excisional Biopsy is the preferred method for diagnosing Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease). It involves the surgical removal of an entire enlarged lymph node, providing the pathologist with the best architectural context to identify characteristic features. Excised lymph node tissues are then sent to the laboratory for examination using different methods.

- Histopathology: Microscopic examination of the biopsied tissue is essential for identifying Reed-Sternberg cells, large, abnormal lymphocytes often described as having an “owl-eye” appearance with multiple nuclei. The presence of Reed-Sternberg cells, within the appropriate inflammatory background, is the hallmark of classical Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease). The histopathology of the lymph node biopsy uses Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) stain as the primary method to look for the presence of Reed-Sternberg (RS) cells.

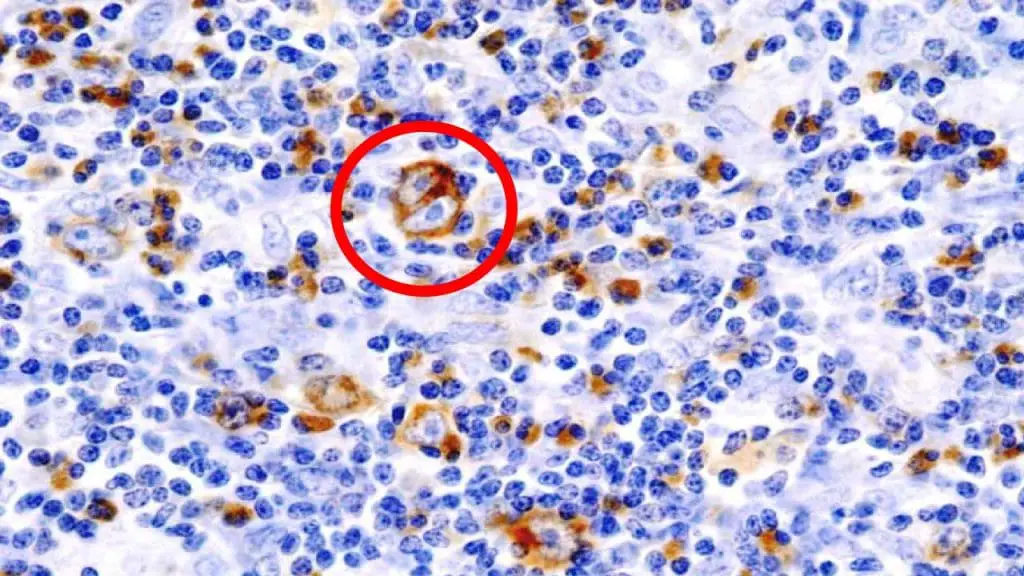

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC): This technique uses antibodies to detect specific proteins (antigens) on the surface of the lymphoma cells. In classical Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease), Reed-Sternberg cells typically show a characteristic immunophenotype:

- Positive for CD30 and CD15.

- Usually negative for CD20 (a B-cell marker) and CD45 (a marker common to most hematopoietic cells).

- Positive for PAX5 (a B-cell transcription factor, though often weaker than in B-NHL).

- EBV-LMP1 (Epstein-Barr virus Latent Membrane Protein 1): May be positive in a subset of cases, particularly in mixed cellularity and lymphocyte-depleted subtypes.

- Flow Cytometry: While biopsy with IHC is the primary diagnostic tool, flow cytometry on lymph node aspirates or tissue can be used as an adjunct in some cases to analyze cell surface markers.

Blood Tests

While blood tests alone cannot diagnose Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease), they provide valuable information about the patient’s overall health, the extent of the disease, and prognosis.

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) with differential: May reveal abnormalities like anemia (low red blood cells), lymphopenia (low lymphocytes), neutrophilia (high neutrophils), or eosinophilia (high eosinophils), which can correlate with disease extent and prognosis.

- Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR): A non-specific marker of inflammation, often elevated in Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) and associated with a worse prognosis in some studies.

- Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH): Elevated levels can indicate increased cell turnover and may correlate with the bulk of the disease and a poorer prognosis.

- Liver and Kidney Function Tests: Assess organ involvement or dysfunction, which can be part of advanced-stage disease or affect treatment options.

- Serum Albumin: Low levels are associated with a poorer prognosis.

- Beta-2 Microglobulin: Elevated levels can indicate a higher tumor burden and poorer prognosis.

- Viral Serology (HIV, Hepatitis B and C): Important to assess as these infections can influence treatment strategies and outcomes. EBV serology is not diagnostic but can provide supportive information.

Investigations for Staging of Hodgkin Lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease)

For staging Hodgkin Lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease), laboratory investigations complement imaging and clinical findings to determine the extent of the disease.

- Positron Emission Tomography-Computed Tomography (PET-CT) has become the preferred and most crucial imaging modality for staging HL. It combines functional imaging (PET, detecting metabolically active cells like lymphoma) with anatomical imaging (CT, providing detailed structural information). It provides accurate identification of nodal and extranodal involvement, including spleen, liver, bone marrow, and other organs. It is essential for the Lugano classification, the current standard staging system for Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease).

Bone Marrow Biopsy: While a tissue sample, it’s crucial for staging as it detects Stage IV disease (bone marrow involvement). It is often considered in patients with advanced-stage disease, “B” symptoms, unexplained cytopenias, or high-risk histology, as PET-CT sensitivity for bone marrow involvement is still being defined.

While PET-CT is preferred, contrast-enhanced CT scans of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis are still important, especially when PET-CT is unavailable or for specific purposes.

Chest X-ray: Historically used to assess for mediastinal involvement, chest X-ray is now largely replaced by CT due to its lower sensitivity and specificity. May still be used as an initial screening tool in some settings but is not sufficient for accurate staging.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): It has a limited role in initial staging of Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) but may be used in evaluating suspected spinal cord compression or brain involvement. It can be used for staging in pregnant patients to minimize radiation exposure.

Once a diagnosis of Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) is confirmed, the doctor will need to determine the stage of the disease. The stage of Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) is determined by the location of the cancer and the presence of certain clinical signs. The stage of Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) is important for determining the prognosis for patients with Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) and for guiding treatment decisions.

Staging of Hodgkin Lymphoma (Hodgkin’s Disease)

The staging of Hodgkin Lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) is crucial for guiding treatment and predicting prognosis. It involves a comprehensive assessment of the extent of the disease, relying heavily on imaging studies, complemented by clinical findings and laboratory investigations. The current standard staging system is the Lugano classification, which integrates PET-CT findings, while the older Ann Arbor system (with Cotswolds modification) is still relevant.

Lugano Classification

| Stage | Description | PET-CT Considerations |

| I | Involvement of a single lymph node region or lymphoid structure (e.g., spleen, thymus, Waldeyer’s ring). | Single focus of FDG-avid disease in one region. |

| IE | Single extralymphatic site in the absence of nodal involvement (rare in HL). | Single focus of FDG-avid disease in an extralymphatic site without nodal involvement. |

| II | Involvement of two or more lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm. | Two or more foci of FDG-avid disease on the same side of the diaphragm. |

| IIE | Contiguous extralymphatic extension from a nodal site with or without involvement of other 1 nodal regions on the same side of the diaphragm. | FDG-avid nodal disease with direct extension into an adjacent extralymphatic site, potentially with other FDG-avid nodes on the same side of the diaphragm. |

| III | Involvement of lymph node regions on both sides of the diaphragm; may include the spleen (IIIS). | FDG-avid disease in nodal regions above and below the diaphragm. Splenic involvement is defined by FDG uptake higher than the liver and/or splenomegaly. |

| IIIE | Involvement of lymph node regions on both sides of the diaphragm with localized extralymphatic involvement. | FDG-avid nodal disease above and below the diaphragm with localized FDG-avid disease in an extralymphatic site. |

| IIIS | Involvement of lymph node regions above the diaphragm with splenic involvement. | FDG-avid disease in nodal regions above the diaphragm with splenic involvement (FDG uptake > liver and/or splenomegaly). |

| IIIE+S | Involvement of lymph node regions on both sides of the diaphragm with splenic and localized extralymphatic involvement. | FDG-avid nodal disease above and below the diaphragm, splenic involvement (FDG uptake > liver and/or splenomegaly), and localized FDG-avid disease in an extralymphatic site. |

| IV | Disseminated involvement of one or more extralymphatic organs (e.g., bone marrow, lung, liver) with or without associated lymph node involvement. | Multiple foci of FDG-avid disease in one or more extralymphatic organs (beyond direct extension from nodes), with or without FDG-avid nodal involvement. Bone marrow involvement is defined by diffuse or multifocal FDG uptake. |

Ann Arbor Staging System

The Ann Arbor staging system is based on the location of the cancer and the presence of certain clinical signs.

The Ann Arbor staging system for Hodgkin lymphoma is as follows:

- Stage I: The cancer is limited to a single lymph node region or to a single organ outside of the lymphatic system.

- Stage II: The cancer is limited to two or more lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm, or to a single organ outside of the lymphatic system and to adjacent lymph node regions.

- Stage III: The cancer is located in lymph node regions on both sides of the diaphragm, or it is located in the spleen or bone marrow.

- Stage IV: The cancer is disseminated to multiple organs outside of the lymphatic system for example it refers to diffuse or disseminated disease in the bone marrow, liver and other extranodal sites.

In addition to the stage number, the letters A, B, E, or X may be used to further classify the stage of Hodgkin lymphoma.

- Category A: The patient does not have B symptoms (unexplained fever above 38 °C, night sweats, or weight loss).

- Category B: The patient has B symptoms.

- Category E: The patient has Hodgkin lymphoma cells in organs or tissues outside of the lymphatic system.

- Category X: Indication of bulky disease, a lymphoma that is greater than 10 cm (4 inches) wide

For example, a patient with Hodgkin lymphoma that is localized to a single lymph node region in the neck and who does not have B symptoms would be classified as stage I, category A (I, A). A patient with Hodgkin lymphoma that is located in lymph node regions on both sides of the diaphragm and who has B symptoms would be classified as stage III, category B (III, B).

Hodgkin Lymphoma (Hodgkin’s Disease) Treatment

The treatment of Hodgkin Lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) is highly effective and individualized based on the stage, risk factors, and response to therapy. A multidisciplinary team utilizes chemotherapy, radiation therapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy, with stem cell transplantation reserved for relapsed or refractory disease. PET-CT plays a crucial role in staging and response assessment, and long-term surveillance is essential to monitor for relapse and treatment-related complications.

Main Treatment Modalities

- Chemotherapy: The backbone of Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) treatment. Various combination regimens are used, with the most common being ABVD (Doxorubicin, Bleomycin, Vinblastine, Dacarbazine). Other regimens like BEACOPP (Bleomycin, Etoposide, Doxorubicin, Cyclophosphamide, Vincristine, Procarbazine, Prednisone), AVD (Doxorubicin, Vinblastine, Dacarbazine), and Stanford V are used in specific situations. The number of cycles depends on the stage and risk factors.

- Radiation Therapy: Often used in combination with chemotherapy, especially for early-stage disease or bulky disease. Involved-site radiation therapy (ISRT) is the standard approach, targeting only the initially involved areas to minimize long-term side effects.

- Immunotherapy: Plays an increasing role, particularly in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease). Checkpoint inhibitors like Nivolumab and Pembrolizumab, and antibody-drug conjugates like Brentuximab Vedotin, have shown significant efficacy.

- Targeted Therapy: Brentuximab Vedotin, an antibody-drug conjugate targeting CD30 (a marker on Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) cells), is used in both frontline (for specific advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease)) and relapsed/refractory settings.

- High-Dose Chemotherapy and Stem Cell Transplant: Primarily used for relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) in eligible patients. Autologous stem cell transplant (using the patient’s own stem cells) is the standard approach. Allogeneic transplant (using donor stem cells) may be considered in select cases.

- Surgery: Primarily limited to obtaining biopsies for diagnosis and staging. Splenectomy is rarely performed as a primary treatment but might be considered in specific, unusual circumstances like symptomatic splenomegaly unresponsive to other treatments or in certain research contexts.

Stage-Based Treatment Strategies (General Principles)

Treatment is largely guided by the Lugano stage.

- Early-Stage (I and II) Favorable Risk: Typically treated with a shorter course of chemotherapy (e.g., 2-4 cycles of ABVD) followed by involved-site radiation therapy (ISRT). Some highly selected patients with very favorable characteristics might receive chemotherapy alone or even less intensive therapy.

- Early-Stage (I and II) Unfavorable Risk: Usually requires more intensive chemotherapy (e.g., 4-6 cycles of ABVD or other regimens) followed by ISRT.

- Advanced-Stage (III and IV): Primarily treated with combination chemotherapy (e.g., 6-8 cycles of ABVD or escalated BEACOPP, sometimes with the addition of immunotherapy like Nivolumab or Brentuximab Vedotin). Radiation therapy may be considered for residual bulky disease after chemotherapy.

Response Assessment and Follow-up

- Interim PET-CT: Often performed after 2-4 cycles of chemotherapy to assess early treatment response (using the Deauville criteria). This helps determine if further treatment intensification or de-escalation is needed.

- End-of-Treatment PET-CT: Crucial for confirming complete remission.

- Surveillance: Regular follow-up appointments are essential to monitor for relapse and long-term complications of treatment, such as secondary malignancies, cardiovascular issues, and endocrine dysfunction (e.g., hypothyroidism, especially after neck/chest radiation). Routine scans are generally not recommended in patients with negative end-of-treatment PET-CT unless clinically indicated by new symptoms or findings.

Management of Relapsed or Refractory Hodgkin Lymphoma (Hodgkin’s Disease)

Treatment for relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) is more complex and depends on factors like the initial treatment, time to relapse, and patient factors.

- Salvage Chemotherapy: Different chemotherapy regimens are used (e.g., ICE, DHAP, ESHAP).

- High-Dose Chemotherapy and Autologous Stem Cell Transplant: The standard of care for eligible patients with chemosensitive relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease).

- Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplant: May be considered in selected patients who fail autologous transplant.

- Immunotherapy: Checkpoint inhibitors (Nivolumab, Pembrolizumab) and antibody-drug conjugates (Brentuximab Vedotin) have shown significant activity in this setting.

- Novel Agents and Clinical Trials: Participation in clinical trials evaluating new therapies is often encouraged.

Special Considerations

- Pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) Treatment approaches differ and are tailored to minimize long-term toxicities in growing children.

- Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) in Pregnancy: Management requires a careful balance between treating the mother and minimizing risks to the fetus. Treatment strategies are often adapted based on the trimester.

- Elderly Patients: Treatment may need to be modified due to comorbidities and potential intolerance to intensive chemotherapy.

- Nodular Lymphocyte-Predominant Hodgkin Lymphoma (NLPHL): Management differs from classical Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) and often involves less intensive approaches, with Rituximab (an anti-CD20 antibody) sometimes used. Splenectomy might have a role in some NLPHL cases.

Hodgkin Lymphoma Prognosis

The Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) prognosis is generally good. With treatment, most patients with Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) can achieve remission. However, the prognosis for patients with Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) depends on a number of factors, including the stage of the disease, the patient’s age and health, and the type of treatment received.

Patients with early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma (stage I or II) have a very good prognosis and can be cured with radiation therapy or chemotherapy. Patients with advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma (stage III or IV) have a worse prognosis, but many patients can still be cured with more aggressive treatment regimens.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the survival rate for Hodgkin lymphoma?

The survival rate for Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) varies depending on several factors, but overall, it is a highly treatable cancer with encouraging statistics.

General survival rates

- 5-year relative survival rate: This compares people with Hodgkin lymphoma to the general population. In the United States, it’s around 89%, meaning 89% of people with the disease are expected to survive at least 5 years after diagnosis.

- 10-year relative survival rate: This figure rises to around 80%.

Survival rates by stage

- Early-stage (localized): 5-year survival rate is 93-95%.

- Advanced-stage: 5-year survival rate is around 83%.

Factors affecting survival

- Stage of cancer: Earlier stages have better prognoses.

- Age and overall health: Younger, healthier individuals tend to fare better.

- Subtype of Hodgkin’s lymphoma: Certain subtypes have slightly different survival rates.

- Treatment response: How well the cancer responds to therapy plays a crucial role.

Who is most likely to get Hodgkin lymphoma or Hodgkin’s disease?

While anyone can develop Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease), certain factors put some individuals at higher risk:

AgeYoung adults (20-40 years old): This is the most common age group for diagnosis, with a second peak occurring in older adults (over 75).

Gender: Men are slightly more likely than women to develop Hodgkin lymphoma. However, the specific subtype called nodular sclerosis Hodgkin lymphoma is more common in women.

Weakened immune system: Individuals with HIV/AIDS, autoimmune diseases, or who have received organ transplants have a higher risk due to compromised immune function. Taking medications that suppress the immune system, such as after an organ transplant, can increase risk.

Previous infections: Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), responsible for mononucleosis, is linked to some Hodgkin lymphoma cases, although the exact connection isn’t fully understood.

Family history: Siblings or identical twins of someone with Hodgkin lymphoma have a slightly higher risk, though still uncommon.

Is lymphoma a type of leukemia?

Both lymphoma and leukemia are cancers affecting white blood cells and are considered blood cancers. However, lymphoma is not a type of leukemia. They are distinct categories of hematologic malignancies that differ in their origin and primary sites of involvement.

| Feature | Leukemia | Lymphoma |

| Origin | Bone marrow | Lymphatic system |

| Primary Site | Blood and bone marrow | Lymph nodes and other lymphatic tissues |

| Cancerous Cell | Immature or abnormal blood cells (blasts) | Lymphocytes (specific subtypes) |

| Typical Presentation | Anemia, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, high WBC count, bone pain | Swollen lymph nodes, B symptoms (fever, night sweats, weight loss), fatigue |

| Spread Pattern | Primarily in the bloodstream | Primarily through the lymphatic system |

| Mass Formation | Less common as localized solid tumors | Common, forming tumors in lymph nodes and organs |

| Bone Marrow Involvement | Primary site of disease | Can be involved, especially in later stages, but not the primary origin |

| Key Categories | Acute (AML, ALL), Chronic (CML, CLL) | Hodgkin Lymphoma, Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL) |

Is lymphoma benign or malignant?

The term “lymphoma” itself doesn’t specify whether it’s benign or malignant. It refers to a group of cancerous and non-cancerous tumors that develop in the lymphatic system, which plays a crucial role in your immune system.

| Feature | Benign Lymphoma | Malignant Lymphoma |

|---|---|---|

| Growth Pattern | Non-cancerous; lymphocytes don’t spread uncontrollably | Cancerous; lymphocytes grow abnormally and spread through lymph nodes and potentially other organs |

| Examples | Castleman’s disease, Lymphoid hyperplasia, Lipoma-like lymphoma | Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (various subtypes) |

| Symptoms | May include swollen lymph nodes, fever, night sweats, fatigue, weight loss (depending on type and severity) | Similar symptoms as benign lymphoma, but typically more persistent and severe |

| Spread | Localized, mostly affecting specific lymph node groups | Can spread to other lymph node groups, organs, and the bloodstream |

| Prognosis | Good; no risk of spreading or becoming cancerous | Varies depending on stage and type; some types highly treatable, others require ongoing management |

| Treatment | May involve monitoring, medication (steroids), or surgery; often no treatment needed | Typically involves chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or stem cell transplantation |

| Risk Factors | Unknown or linked to autoimmune disorders, infections, or abnormal blood vessel development | Risk factors not fully understood; may include age, weakened immune system, genetic predisposition |

| Overall Impact | Usually manageable with minimal impact on lifespan | Can significantly impact quality of life and lifespan, though advancements in treatment offer improved outcomes |

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. WHO Classification of Tumours, Revised 4th Edition, Volume 2. 2017.

- Che Y, Ding X, Xu L, Zhao J, Zhang X, Li N, Sun X. Advances in the treatment of Hodgkin’s lymphoma (Review). Int J Oncol. 2023 May;62(5):61. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2023.5509. Epub 2023 Apr 7. PMID: 37026506; PMCID: PMC10147096.

- Eichenauer DA, Aleman BMP, André M, Federico M, Hutchings M, Illidge T, Engert A, Ladetto M; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Hodgkin lymphoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018 Oct 1;29(Suppl 4):iv19-iv29. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy080. PMID: 29796651.

- Hoppe RT, Advani RH, Ai WZ, Ambinder RF, Armand P, Bello CM, Benitez CM, Chen W, Dabaja B, Daly ME, Gordon LI, Hansen N, Herrera AF, Hochberg EP, Johnston PB, Kaminski MS, Kelsey CR, Kenkre VP, Khan N, Lynch RC, Maddocks K, McConathy J, Metzger M, Morgan D, Mulroney C, Pullarkat ST, Rabinovitch R, Rosenspire KC, Seropian S, Tao R, Torka P, Winter JN, Yahalom J, Yang JC, Burns JL, Campbell M, Sundar H. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Hodgkin Lymphoma, Version 2.2022. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022 Apr;20(4):322-334. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2022.0021. PMID: 35390768.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®) NCCN Guidelines for Patients® Hodgkin Lymphoma. 2022.

- Adler EM. Living with Lymphoma: A Patient’s Guide (Johns Hopkins Press Health Books (Paperback)). 2016.

- Engert A, Younes A. Hodgkin Lymphoma: A Comprehensive Overview (Hematologic Malignancies) 3rd Edition (Springer). 2020.

- Hoppe, RT, Mauch PM, Armitage JO, Volker D, Weiss LM. Hodgkin Lymphoma 2nd Edition (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins). 2007.