TL;DR

Infectious mononucleosis is an acute viral illness (primarily EBV) with classic triad: pharyngitis, fever, lymphadenopathy.

- Epidemiology ▾: Common in adolescents/young adults, spread globally, primarily via saliva.

- Causes ▾: Primarily Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV), less common causes include CMV, Toxoplasma, HIV.

- Symptoms ▾: Sore throat, fever, swollen lymph nodes, fatigue, malaise, headache, potential rash, splenomegaly, hepatomegaly.

- Diagnosis ▾:

- Hematology: Leukocytosis, lymphocytosis, atypical lymphocytes.

- Serology: Positive heterophile antibody (Monospot), EBV-specific antibodies (IgM VCA indicates acute).

- LFTs: Mildly elevated.

- Differential Diagnosis ▾: Strep throat, other viral pharyngitis, CMV, toxoplasmosis, acute HIV, lymphoma, drug reactions.

- Treatment & Management ▾: Supportive care (rest, hydration, pain/fever control), avoid contact sports. Antivirals not routine. Corticosteroids for specific complications.

- Complications ▾: Splenic rupture (rare but serious), airway obstruction, hematologic issues, neurological/cardiac problems (rare), post-viral fatigue.

- Prevention ▾: Good hygiene, avoid sharing saliva. No vaccine available.

- Prognosis: Usually self-limiting with full recovery. Fatigue can be prolonged. Lifelong EBV latency.

*Click ▾ for more information

Introduction

Infectious mononucleosis is a common illness frequently encountered in clinical practice It is also known as mono or glandular fever. This syndrome is particularly prevalent among adolescents and young adults, representing a significant portion of infectious disease cases in this demographic. Given its widespread occurrence and the potential for both acute discomfort and, in rare instances, serious complications, a comprehensive understanding of infectious mononucleosis is essential

Brief History

The understanding of infectious mononucleosis has evolved over time. The condition was initially described in the 1920s, with the term “infectious mononucleosis” coined to characterize a syndrome involving fever, sore throat, and enlarged lymph nodes, accompanied by specific changes in the blood, such as an increase in lymphocytes and the presence of atypical mononuclear cells.

A significant milestone in understanding this disease was the recognition in 1932 of its association with a positive heterophile antibody test. However, it was not until 1968 that the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) was definitively identified as the primary causative agent of infectious mononucleosis.

Typically, the acute phase of infectious mononucleosis resolves within 2 to 4 weeks, although the symptom of fatigue can persist for a more extended period, sometimes lasting for several months. This variability in the duration of symptoms underscores the importance of patient education and appropriate management strategies.

What is Infectious Mononucleosis?

Infectious mononucleosis is an acute viral illness primarily caused by the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). It is often referred to as “mono,” “glandular fever,” or colloquially, the “kissing disease” due to its common mode of transmission through saliva.

Characteristically, infectious mononucleosis is defined by a classic triad of symptoms:

- Pharyngitis: Sore throat, often severe.

- Fever: Typically high-grade.

- Lymphadenopathy: Swollen lymph nodes, especially in the neck.

However, it’s important to note that other symptoms like profound fatigue, malaise, headache, and sometimes enlargement of the spleen and liver can also occur.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

The reported annual incidence of symptomatic infectious mononucleosis in the general population of the United States is estimated to be around 45-500 cases per 100,000 people per year. The incidence is highest among adolescents and young adults aged 15-24 years. In this age group, the annual incidence can range from 200 to 800 cases per 100,000.

The age at which primary EBV infection occurs significantly influences whether infectious mononucleosis symptoms develop.

- Early Childhood: In many parts of the world, particularly developing countries and lower socioeconomic groups, primary EBV infection often occurs in early childhood (before the age of 5). In these cases, the infection is usually asymptomatic or presents with mild, non-specific symptoms that may be indistinguishable from other common childhood illnesses.

- Adolescence and Young Adulthood: In industrialized nations and higher socioeconomic groups, primary EBV infection is often delayed until adolescence or young adulthood (15-25 years old). When primary infection occurs in this age group, it leads to symptomatic infectious mononucleosis (mono) in a significant proportion of individuals (estimates range from 30% to 70%). This is likely due to a more robust immune response at this age.

- Older Adults: Primary EBV infection in older adults is less common and may present with atypical symptoms.

Causes and Pathogenesis of Infectious Mononucleosis (Mono)

The primary agent responsible for the majority of cases of infectious mononucleosis (mono) is the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). EBV is a member of the herpesvirus family, also known as human herpesvirus type 4. EBV is one of the most common human viruses, infecting the vast majority of the world’s population by adulthood.

The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is primarily transmitted through saliva. The main modes of transmission include:

- Kissing: This close contact allowing for direct saliva exchange is the most well-known mode, hence the nickname “kissing disease.”

- Sharing drinks and food: When individuals share cups, water bottles, eating utensils, or even food that has been in someone else’s mouth, they can transmit the virus.

- Sharing personal items: Items that can become contaminated with saliva, such as toothbrushes, lip balm, or anything else put in the mouth, can spread EBV if shared.

- Contact with toys: Young children often put toys in their mouths, and if an EBV-infected child does this, others can be exposed.

- Respiratory droplets: Although less efficient than direct saliva exchange, the virus can potentially spread through coughing or sneezing, similar to other respiratory viruses.

Less common routes of transmission include:

- Blood transfusion: EBV can be transmitted through infected blood products, although screening procedures have significantly reduced this risk.

- Organ transplantation: Similar to blood transfusions, the virus can be transmitted via an infected organ.

- Sexual contact: EBV has been found in genital secretions (semen and cervical secretions), suggesting a possible, though less common, route of transmission through sexual contact.

- Mother to child (vertical transmission): Transmission from a mother to her unborn baby is possible but not a primary route.

Following exposure to EBV, the incubation period, which is the time between infection and the onset of symptoms, is typically 4 to 6 weeks.

The pathogenesis of infectious mononucleosis (mono) primarily involves the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) entering the body through saliva and initially infecting epithelial cells in the oropharynx. EBV primarily targets B lymphocytes (B cells) and epithelial cells of the oropharynx.

EBV infects B lymphocytes by binding to the CD21 receptor, establishing a latent infection within these cells and driving their proliferation. This proliferation of infected B cells, coupled with the robust host immune response – particularly the activation and proliferation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (atypical lymphocytes) aimed at eliminating the infected B cells – is responsible for the characteristic infectious mononucleosis (mono) symptoms, including pharyngitis, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and fatigue. While the acute infection resolves, EBV persists in a latent state within B cells for life, with intermittent shedding in saliva contributing to its widespread transmission.

While EBV is highly prevalent, with most adults having been infected, the development of symptomatic mononucleosis is not a universal outcome of EBV infection. As mentioned earlier, primary EBV infection in childhood is often subclinical or mild. Symptomatic infectious mononucleosis (mono) typically arises when the primary EBV infection is delayed until adolescence or young adulthood.

Other Causes of Infectious Mononucleosis (Mono)

Although EBV is the most common cause, accounting for 80-90% of cases of infectious mononucleosis, it is important to note that other viral agents can also cause a clinically similar syndrome.

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV): Another member of the Herpesviridae family, CMV can cause a mononucleosis-like syndrome, often referred to as “CMV mononucleosis.” This tends to have a more insidious onset and may lack the prominent pharyngitis seen in typical EBV-related IM. Heterophile antibody tests are usually negative in CMV mononucleosis.

- Toxoplasma gondii: This protozoan parasite can also cause a syndrome resembling infectious mononucleosis, characterized by lymphadenopathy and fatigue, but typically without significant pharyngitis. Heterophile antibody tests are also negative.

- Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV): During the acute seroconversion phase of HIV infection, some individuals may experience symptoms that overlap with infectious mononucleosis, including fever, lymphadenopathy, and sore throat. However, other signs and symptoms of acute HIV infection are usually present, and specific HIV testing is required for diagnosis.

- Other Viruses (Rarely): In rare instances, other viruses like human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) have been implicated in mononucleosis-like illnesses.

Infectious Mononucleosis (Mono) Symptoms and Signs

The clinical presentation of infectious mononucleosis (mono) can vary among individuals, but several key symptoms are commonly observed.

Classic Triad (Most Characteristic)

- Pharyngitis (Sore Throat): Often the first or most prominent symptom. It can range from mild discomfort to severe pain, making swallowing difficult (odynophagia). The throat often appears erythematous (red) and may have a white or grayish-white exudate (pus-like coating) on the tonsils, mimicking streptococcal pharyngitis (“strep throat”). Swelling of the tonsils can be significant, sometimes leading to difficulty breathing or swallowing.

- Fever: Typically high-grade, often ranging from 101°F to 104°F (38.3°C to 40°C). The fever can be intermittent or persistent and usually lasts for several days to a week or two. It may be accompanied by chills.

- Lymphadenopathy (Swollen Lymph Nodes): Characteristically involves the posterior cervical lymph nodes (at the back of the neck), but can affect lymph nodes throughout the body, including anterior cervical, axillary (armpit), and inguinal (groin) nodes. The swollen lymph nodes are usually tender to the touch and feel firm and rubbery. The enlargement is often symmetrical, affecting both sides of the body.

Other Common Symptoms

- Fatigue: Often the most debilitating and prolonged symptom. It ranges from mild tiredness to profound exhaustion that interferes with daily activities. The fatigue may persist for weeks or even months after other symptoms have resolved.

- Malaise: A general feeling of discomfort, illness, and lack of well-being.

- Headache: Varying in intensity and location.

- Myalgia (Muscle Aches): Generalized muscle pain and stiffness.

- Anorexia (Loss of Appetite)

- Rash: A maculopapular rash (flat, red spots with small bumps) can occur in some individuals. A characteristic finding is a rash that develops in a high percentage of patients with infectious mononucleosis (mono) who are treated with ampicillin or amoxicillin (antibiotics often mistakenly prescribed for suspected strep throat). This rash is not an allergic reaction to the antibiotic in the typical sense but rather a drug-viral interaction. Petechiae (small, pinpoint red spots) may be seen on the palate (roof of the mouth).

Physical Examination Findings

- Tonsillar Enlargement and Exudates: As mentioned in pharyngitis, the tonsils are often swollen and may have a white or grayish exudate.

- Palatal Petechiae: Small, red or purple spots on the soft palate are a relatively specific finding for infectious mononucleosis (mono).

- Splenomegaly (Enlarged Spleen): Palpable in a significant proportion of patients (estimated 50-60%) during the second and third weeks of illness. The spleen is usually mildly to moderately enlarged and is typically soft. Splenomegaly is a key reason for advising patients to avoid contact sports due to the risk of splenic rupture.

- Hepatomegaly (Enlarged Liver): Less common than splenomegaly (around 10-20% of patients). The liver may be mildly enlarged and tender.

- Jaundice: Yellowing of the skin and eyes is rare in uncomplicated infectious mononucleosis (mono) but can occur if there is significant liver involvement.

How long does infectious mononucleosis (mono) symptoms last?

The typical duration and progression of symptoms in infectious mononucleosis are important for understanding the natural course of the illness.

- Acute symptoms generally last for 1 to 2 months (or 2 to 8 weeks).

- Sore throat is often most severe during the first 3 to 5 days before gradually resolving over the subsequent 7 to 10 days.

- Fatigue can be the most persistent symptom, frequently lingering for several weeks or even months after the resolution of other acute manifestations.

- Lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly may take longer to resolve compared to other acute symptoms.

It is crucial to recognize that the presentation and duration of symptoms can vary considerably among individuals with infectious mononucleosis. Not all patients will exhibit the classic triad of fever, pharyngitis, and lymphadenopathy, and the intensity and duration of each symptom can differ significantly from person to person.

Furthermore, the occurrence of a rash following the administration of ampicillin or amoxicillin in a patient with suspected infectious mononucleosis is a well-recognized phenomenon. This is not typically indicative of a true penicillin allergy and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a patient presenting with pharyngitis who develops a rash after starting these antibiotics.

Laboratory Investigations for Infectious Mononucleosis

Laboratory investigations play a crucial role in confirming the clinical suspicion of infectious mononucleosis. These tests help differentiate infectious mononucleosis from other illnesses with similar symptoms. The main categories of laboratory investigations include hematological findings and serological tests for EBV.

Hematological Findings (Complete Blood Count with Differential)

A complete blood count (CBC) with a white blood cell (WBC) differential is often the first-line investigation and can provide suggestive evidence of infectious mononucleosis (mono). Typical findings include:

- Leukocytosis: An elevated total white blood cell count, usually ranging from 10,000 to 20,000 cells/mm³ (normal range is typically 4,000 to 10,000 cells/mm³).

- Lymphocytosis: An increased percentage and absolute number of lymphocytes. Lymphocytes usually make up more than 50% of the total WBC count, and the absolute lymphocyte count is typically elevated (>4,000/mm³).

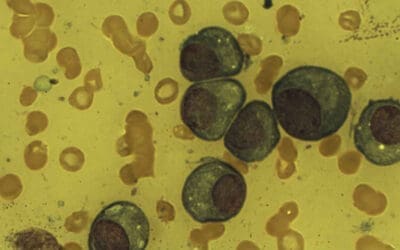

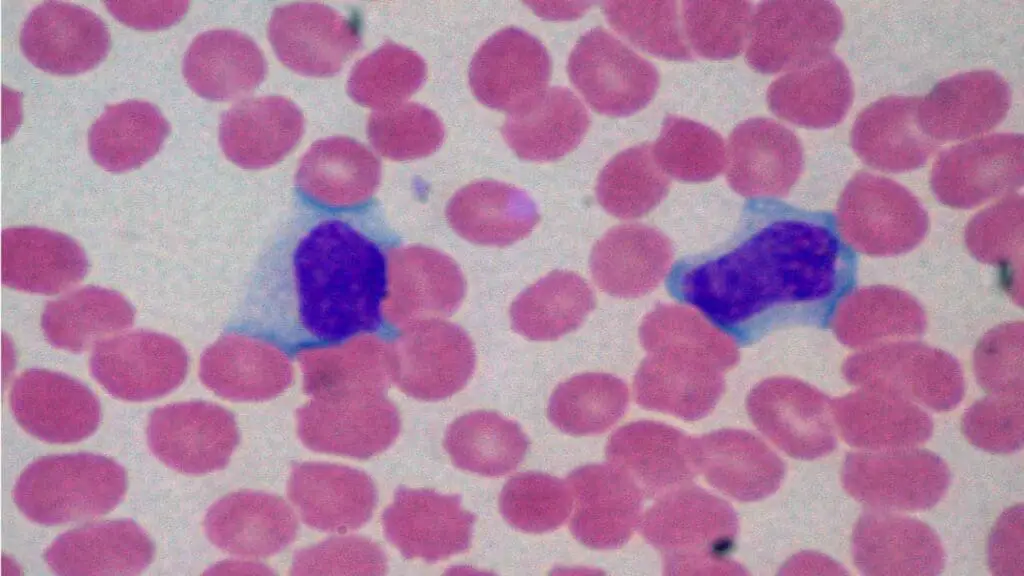

- Atypical Lymphocytes (Downey Cells): The presence of characteristic atypical lymphocytes on the peripheral blood smear is a hallmark of infectious mononucleosis (mono). These are morphologically distinct lymphocytes:

- They are larger than normal lymphocytes.

- They have a pleomorphic (varied) appearance with abundant cytoplasm, which may be vacuolated or basophilic (dark blue staining).

- The nucleus can be large, irregular, and sometimes folded or lobulated, with a less condensed chromatin pattern compared to normal lymphocytes.

- While highly suggestive of infectious mononucleosis (mono), atypical lymphocytes can also be seen in other viral infections (e.g., CMV, HHV-6, acute HIV) and sometimes in drug reactions. The percentage of atypical lymphocytes usually peaks during the second or third week of illness.

- Thrombocytopenia: A mild decrease in platelet count (thrombocytopenia) may be observed in some patients, but severe thrombocytopenia is uncommon in uncomplicated infectious mononucleosis (mono).

- Anemia: Anemia is usually not a feature of uncomplicated infectious mononucleosis (mono), but autoimmune hemolytic anemia can occur as a rare complication.

Serological Tests for Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV)

These tests detect antibodies produced by the body in response to EBV infection and are crucial for confirming the diagnosis, especially when clinical and hematological findings are suggestive.

Heterophile Antibody Tests (Monospot Test)

These rapid and relatively inexpensive slide agglutination tests detect heterophile antibodies, which are IgM antibodies produced during EBV infection that can agglutinate (clump) animal red blood cells (typically horse, sheep, or beef erythrocytes).

The heterophile antibody test is most reliable during the second to fourth week of illness. It may be negative early in the course of the infection (false negative) and can remain positive for several weeks or even months after the acute illness.

Due to its limitations, including the potential for false negative and false positive results, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) does not recommend the Monospot test for general use in diagnosing infectious mononucleosis.

- Interpretation:

- Positive result in a patient with suggestive symptoms: Strongly supports the diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis (mono).

- Negative result early in the illness: Does not rule out infectious mononucleosis (mono), and repeat testing may be necessary in 1-2 weeks if clinical suspicion remains high.

- Negative result in children under 5 years: Infectious mononucleosis (mono) should not be excluded based on a negative Monospot alone, and EBV-specific antibody testing may be more helpful.

EBV-Specific Antibody Tests

EBV-specific antibody tests offer a more specific and sensitive approach to diagnosing infectious mononucleosis, especially in cases where the heterophile antibody test is negative or in young children, who are less likely to produce heterophile antibodies.

Common EBV-specific antibodies measured include:

- Viral Capsid Antigen (VCA) IgM: Appears early in the acute phase of infection (often before or at the same time as heterophile antibodies), peaks within a few weeks, and usually disappears within 4-6 months. A positive VCA IgM indicates a recent or current primary EBV infection.

- Viral Capsid Antigen (VCA) IgG: Appears shortly after VCA IgM, peaks within a few weeks, and persists for life, indicating past exposure to EBV. A rising titer in paired acute and convalescent sera can also confirm recent infection.

- Early Antigen (EA) IgG and IgD: Antibodies to early antigens (EA-D and EA-R) appear during the acute phase and usually disappear within 3-6 months. They can be positive in reactivated EBV infection or in certain EBV-associated malignancies but are not always present in primary IM.

- EBV Nuclear Antigen (EBNA) IgG: Antibodies to EBNA appear later in the course of infection, typically 4-6 weeks after the onset of symptoms. Once positive, EBNA IgG persists for life, indicating past EBV infection and the transition to the latent phase.

Different patterns of EBV-specific antibodies can help determine the stage of infection.

| Antibody | Acute Infection (Typical) | Past Infection (Typical) | Susceptible | Reactivation (Possible) |

| Anti-VCA IgM | Positive | Negative/Weak Positive | Negative | Negative/Weak Positive |

| Anti-VCA IgG | Positive | Positive | Negative | Positive |

| Anti-EA (Early Antigen) | Positive (often) | Negative (usually) | Negative | Positive (sometimes) |

| Anti-EBNA (EBV Nuclear Antigen) | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive |

Liver Function Tests (LFTs)

Liver function tests are frequently abnormal in patients with infectious mononucleosis.

- Elevated Transaminases: Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels are often mildly to moderately elevated.

- Elevated Bilirubin: Less commonly, bilirubin levels may be slightly elevated, sometimes leading to mild jaundice.

- Alkaline Phosphatase: May be mildly elevated.

These abnormalities usually resolve spontaneously as the infection subsides.

Differential Diagnosis of Infectious Mononucleosis (Mono)

When a patient presents with symptoms suggestive of infectious mononucleosis (IM), it’s crucial to consider other conditions that can mimic its clinical picture. This process is known as differential diagnosis.

| Feature | Infectious Mononucleosis (IM) | Streptococcal Pharyngitis (“Strep Throat”) | Adenovirus Pharyngitis | Other Viral Pharyngitis (Flu, Cold) | Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Mononucleosis | Toxoplasmosis | Acute HIV Infection |

| Sore Throat | Often severe, exudative | Often severe, exudative | Variable, may have exudates | Usually mild to moderate | Mild or absent | Mild or absent | Common |

| Fever | High-grade | High-grade | Variable | Variable | Often present | Often present | Often present |

| Lymphadenopathy | Posterior cervical prominent, generalized | Anterior cervical prominent, localized | Variable, may be less generalized | Mild, usually anterior cervical | Generalized | Posterior cervical prominent | Generalized |

| Fatigue /Malaise | Profound and prolonged | Less prominent | Variable | Variable | Often significant | Often present | Often significant |

| Splenomegaly | Common (50-60%) | Rare | Rare | Rare | Can occur | Less common | Can occur |

| Palatal Petechiae | Common | Rare | Rare | Rare | Rare | Rare | Rare |

| Rash | Maculopapular (esp. w/ ampicillin) | Rare | May occur | Rare | Rare | Rare | Common |

| Conjunctivitis | Rare | Rare | Common | Rare | Rare | Rare | Rare |

| Respiratory Symptoms | Minimal | Minimal | Common (cough, coryza) | Common (cough, congestion) | Minimal | Minimal | May have cough |

| Rapid Strep/Culture | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

| Atypical Lymphocytes | Often present (hallmark) | Absent | May be present in small numbers | Absent or few | May be present | May be present | May be present |

| Heterophile Antibody Test | ✅ (Monospot) | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

| CMV Serology | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ |

| Toxo Serology | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ |

| HIV Testing | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ |

| CBC Neutrophilia | Absent | Often present | May be present | May be present | Absent | Absent | May be present |

| Other Features | Risk of rheumatic fever | May have lymph node tenderness | Night sweats, weight loss possible |

Treatment and Management of Infectious Mononucleosis

The treatment and management of infectious mononucleosis (mono) primarily focus on supportive care to relieve symptoms and allow the body’s immune system to clear the viral infection.

There is no specific antiviral medication that is routinely recommended or has been proven to significantly shorten the duration or severity of uncomplicated infectious mononucleosis (mono) in immunocompetent individuals.

Supportive Care: The Cornerstone of Management

- Rest: Adequate rest is crucial, especially during the acute symptomatic phase. Fatigue can be significant, and allowing the body to conserve energy aids in recovery. Patients should be encouraged to listen to their bodies and avoid overexertion. The duration of rest needed varies but often lasts for several weeks.

- Hydration: Maintaining good hydration by drinking plenty of fluids (water, juice, broth) is essential to prevent dehydration, especially if there is fever or difficulty swallowing.

- Pain and Fever Management

- Paracetamol (Acetaminophen): Effective for reducing fever and mild to moderate pain, such as sore throat, headache, and muscle aches. It is generally considered safe when used at recommended doses.

- Ibuprofen and other Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): Can also help reduce fever and pain. They may have a slightly longer duration of action than paracetamol.

- Aspirin: Should be avoided in children and adolescents due to the risk of Reye’s syndrome, a rare but serious condition that can affect the liver and brain.

- Sore Throat Relief

- Saltwater Gargles: Warm salt water gargles (1/4 to 1/2 teaspoon of salt in a glass of warm water) can help soothe a sore throat.

- Lozenges and Throat Sprays: Over-the-counter throat lozenges and sprays may provide temporary relief from pain.

- Soft Foods: Eating soft, bland foods can be easier to swallow when the throat is sore. Avoid acidic, spicy, or rough foods.

- Avoidance of Strenuous Activity and Contact Sports: This is particularly important due to the risk of splenic rupture, a rare but serious complication. The spleen can be enlarged and more fragile during IM. Patients are typically advised to avoid contact sports, heavy lifting, and vigorous exercise for at least 3-4 weeks after the onset of symptoms, or until the spleen has returned to its normal size as confirmed by a healthcare professional (often through clinical examination, though imaging may be used in some cases).

Antiviral Medications

- Acyclovir, Valacyclovir, and Famciclovir: These antiviral medications are primarily used for herpes simplex virus (HSV) and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infections. They have limited efficacy against EBV and are generally not routinely recommended for uncomplicated infectious mononucleosis in immunocompetent individuals.

- Ganciclovir and Valganciclovir: These antivirals have some activity against CMV and EBV but are typically reserved for severe EBV infections or EBV-related complications, particularly in immunocompromised patients (e.g., transplant recipients, individuals with HIV). Their use in typical IM is not indicated.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone) are not routinely indicated for uncomplicated infectious mononucleosis (mono) due to potential side effects and the fact that they do not shorten the duration of the illness. The decision to use corticosteroids must be made by a healthcare professional after careful consideration of the risks and benefits for the individual patient.

However, they may be considered in specific situations where severe complications arise, such as:

- Airway Obstruction: Due to severe tonsillar hypertrophy causing difficulty breathing. A short course of corticosteroids can help reduce swelling.

- Severe Thrombocytopenia or Hemolytic Anemia: Autoimmune complications where corticosteroids can help suppress the immune response.

- Neurological Complications: Such as meningitis, encephalitis, or Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Management of Complications

If complications develop, specific treatment will be required.

- Splenic Rupture: A medical emergency that usually requires surgical intervention (splenectomy).

- Airway Obstruction: May require hospitalization, close monitoring, and potentially treatment with corticosteroids or, in rare cases, intubation or tonsillectomy.

- Severe Hematologic Complications: May necessitate hospitalization, blood transfusions, or treatment with corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive agents.

- Neurological Complications: Managed based on the specific neurological syndrome, often involving hospitalization and potentially corticosteroids, antiviral medications (if EBV is directly implicated), or supportive care.

- Myocarditis or Pericarditis: Requires cardiac monitoring and management, which may include anti-inflammatory medications or other cardiac-specific treatments.

Follow-up and Monitoring

Most individuals with uncomplicated infectious mononucleosis (mono) recover fully with supportive care. Follow-up appointments with a healthcare provider are usually recommended to monitor symptoms, ensure resolution of splenomegaly, and address any persistent fatigue or other concerns.

Patients should be advised to return for medical attention if they develop signs of complications, such as severe abdominal pain (suggesting splenic rupture), difficulty breathing, severe headache, stiff neck, or jaundice.

Return to Activity

The timeline for returning to normal activities, including sports, should be individualized and guided by a healthcare professional.

Resolution of splenomegaly is a key factor in determining when it is safe to resume contact sports. This is usually assessed by physical examination, but imaging may be used in some cases.

Persistent fatigue is common, and a gradual return to activity is recommended, increasing the intensity as tolerated.

Complications of Infectious Mononucleosis (Mono)

Infectious mononucleosis is typically a self-limiting illness with a good prognosis.

However, various complications, although generally uncommon, can occur. These can range from relatively mild to life-threatening.

Hematologic Complications

- Thrombocytopenia: A mild decrease in platelet count is relatively common during the acute phase of infectious mononucleosis (mono). Severe thrombocytopenia (very low platelet count leading to increased risk of bleeding) is rare but can occur due to autoimmune destruction of platelets.

- Hemolytic Anemia: This is another rare autoimmune complication where the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks and destroys red blood cells, leading to anemia (low red blood cell count).

- Aplastic Anemia: An extremely rare but serious complication where the bone marrow fails to produce enough blood cells (red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets).

- Neutropenia: A decrease in the number of neutrophils (a type of white blood cell important for fighting bacterial infections) can occur but is usually transient and mild.

Splenic Complications

- Splenomegaly: Enlargement of the spleen is a common finding in infectious mononucleosis (mono). The enlarged spleen is more fragile and susceptible to rupture.

- Splenic Rupture: This is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication. It typically occurs spontaneously or as a result of even minor trauma to the abdomen, often during the second or third week of illness when splenomegaly is maximal. Symptoms include sudden, severe left upper abdominal pain, which may radiate to the left shoulder (Kehr’s sign), dizziness, lightheadedness, and signs of shock (rapid heart rate, low blood pressure). Splenic rupture requires immediate medical attention and often surgical intervention (splenectomy).

Hepatic Complications

- Hepatitis: Mild inflammation of the liver with elevated liver enzymes (transaminases) is common in IM.

- Jaundice: Yellowing of the skin and eyes due to elevated bilirubin levels is less common but can occur if liver involvement is more significant.

- Severe Hepatitis or Liver Failure: These are very rare complications in immunocompetent individuals.

Neurological Complications (Rare)

EBV can sometimes affect the nervous system, leading to various neurological complications.

- Meningitis: Inflammation of the membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord. Symptoms include headache, stiff neck, fever, and photophobia (sensitivity to light).

- Encephalitis: Inflammation of the brain tissue. Symptoms can include altered mental status, seizures, weakness, and neurological deficits.

- Guillain-Barré Syndrome: A rare autoimmune disorder where the immune system attacks the peripheral nerves, leading to progressive muscle weakness and paralysis.

- Bell’s Palsy: Weakness or paralysis of the muscles on one side of the face.

- Optic Neuritis: Inflammation of the optic nerve, which can cause vision problems.

- Cerebellar Ataxia: Problems with coordination and balance.

- Psychiatric Manifestations: Rarely, psychosis or other psychiatric symptoms have been reported.

Cardiac Complications (Very Rare)

Inflammation of the heart tissue or the sac surrounding the heart can occur, but these are extremely rare.

- Myocarditis: Inflammation of the heart muscle, which can lead to chest pain, shortness of breath, and arrhythmias.

- Pericarditis: Inflammation of the pericardium (the sac surrounding the heart), causing chest pain.

Airway Obstruction

Severe swelling of the tonsils and surrounding tissues in the throat can occasionally lead to airway obstruction, causing difficulty breathing. This may require treatment with corticosteroids to reduce swelling or, in rare cases, intubation or even tonsillectomy.

Secondary Infections

While EBV itself is a virus, the immunosuppression that can occur during infectious mononucleosis (mono) may slightly increase the risk of secondary bacterial infections, particularly strep throat (if not already present) or, less commonly, bacterial sinusitis or pneumonia.

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (Post-viral Fatigue)

Some individuals who have had infectious mononucleosis (mono) report prolonged fatigue that persists for months after the acute illness has resolved. The exact link between EBV infection and chronic fatigue syndrome is not fully understood and is an area of ongoing research.

EBV-Associated Malignancies (Rare and Typically in Immunocompromised Individuals)

In rare cases, particularly in individuals with weakened immune systems (e.g., transplant recipients, individuals with HIV, or certain genetic immunodeficiencies), EBV infection can be associated with the development of certain malignancies, such as:

- Burkitt Lymphoma

- Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma

- Hodgkin Lymphoma

- Post-transplant Lymphoproliferative Disorder (PTLD)

Prevention of Infectious Mononucleosis

Preventing infectious mononucleosis primarily revolves around minimizing the transmission of the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), as it is the main causative agent. However, complete prevention can be challenging due to the widespread nature of EBV and the fact that individuals can shed the virus even when asymptomatic.

Good Hand Hygiene: Frequent and thorough handwashing with soap and water for at least 20 seconds is crucial, especially after coughing, sneezing, or being in close contact with others. If soap and water are not available, use an alcohol-based hand sanitizer.

Avoid Sharing Personal Items: Refrain from sharing items that can come into contact with saliva, such as:

- Drinks and food

- Eating utensils (forks, spoons, knives)

- Toothbrushes

- Lip balm, lipstick

- Cigarettes or vaping devices

Covering Coughs and Sneezes: Use a tissue to cover the mouth and nose when coughing or sneezing, and then dispose of the tissue properly. If a tissue isn’t available, cough or sneeze into the elbow rather than the hands.

Avoid Close Contact with Symptomatic Individuals: Limit close contact (kissing, sharing personal items) with individuals who have symptoms of infectious mononucleosis (mono) or other respiratory illnesses.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Is mono considered a STD?

While infectious mononucleosis (mono) is not strictly classified as a sexually transmitted disease (STD) in the same way as chlamydia or gonorrhea, it can be transmitted through sexual contact involving the exchange of bodily fluids.

What are the four stages of mono?

- Incubation Period: This is the time after a person is infected with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) but before he/she experiences any symptoms. During this stage, the virus is multiplying in the body. The incubation period for infectious mononucleosis (mono) is relatively long, typically lasting 4 to 6 weeks. A person is contagious during this time, even though he/she doesn’t feel sick. Some sources might not explicitly list this as a “stage” of the illness itself but rather the period leading up to it.

- Prodromal Stage: This is the initial phase when a person starts to feel the first, often mild, symptoms. These symptoms can be similar to those of other viral illnesses like the common cold or flu. The prodromal stage usually lasts for a few days, typically 3 to 5 days, but can sometimes extend up to a week or two.

- Acute Stage: This is when the classic and more severe infectious mononucleosis (mono) symptoms develop and are most prominent. This stage typically lasts for 2 to 4 weeks, but can sometimes extend for up to 6 weeks.

- Convalescent Stage: This is the recovery phase, during which infectious mononucleosis (mono) symptoms gradually start to improve and eventually resolve. The duration of this stage can vary significantly from person to person, lasting from several weeks to months. The most persistent symptom during convalescence is often fatigue, which can linger even after other symptoms have disappeared. The infected person is still contagious during this phase, although the viral load typically decreases over time.

Please note that the timeline and severity of symptoms can vary among individuals. Some people, especially young children, may have very mild or even asymptomatic infections.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Zhou J, Zhang J, Zhu D, Ma W, Zhong Q, Shen Q, Su J. The diagnostic value of peripheral blood lymphocyte testing in children with infectious mononucleosis. BMC Pediatr. 2024 Nov 16;24(1):746. doi: 10.1186/s12887-024-05228-6. PMID: 39548405; PMCID: PMC11568541.

- Durtschi MS, Pham NS, Hwang CE. Liver Function Test Results Correlate With Spleen Size in Patients With Infectious Mononucleosis. Cureus. 2024 Sep 23;16(9):e70041. doi: 10.7759/cureus.70041. PMID: 39449903; PMCID: PMC11499307.

- Meloni DF, Faré PB, Milani GP, Lava SAG, Bianchetti MG, Renzi S, Bertacchi M, Kottanattu L, Bronz G, Camozzi P. Hemolytic Anemia Linked to Epstein-Barr Virus Infectious Mononucleosis: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J Clin Med. 2025 Feb 15;14(4):1283. doi: 10.3390/jcm14041283. PMID: 40004813; PMCID: PMC11856085.

- Caimi E, Guerini F. Amoxicillin-Induced Parvovirus B19 Infectious Mononucleosis, Mimicking Epstein-Barr Infection. Am J Med. 2025 Mar 12:S0002-9343(25)00165-2. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2025.03.009. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40086771.