TL;DR

Sickle cell anemia is a hereditary chronic hemolytic anemia caused by the production of Hb S (a qualitative hemoglobin defect due to a β-globin gene codon 6 mutation [glutamic acid → valine]).

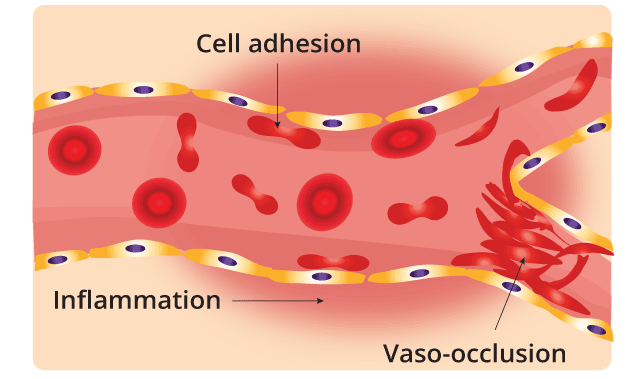

- Pathophysiology ▾: Sickle cell anemia is a genetic disorder characterized by the abnormal production of hemoglobin S. This abnormal hemoglobin distorts red blood cells into a crescent or sickle shape when they lose oxygen. These sickle cells are less flexible and more prone to clumping together, blocking small blood vessels. This blockage, known as vaso-occlusion, leads to severe pain crises, tissue damage, and a cascade of complications, including anemia, organ damage, and stroke. Additionally, the sickle cells have a shorter lifespan, leading to chronic anemia and increased risk of infection.

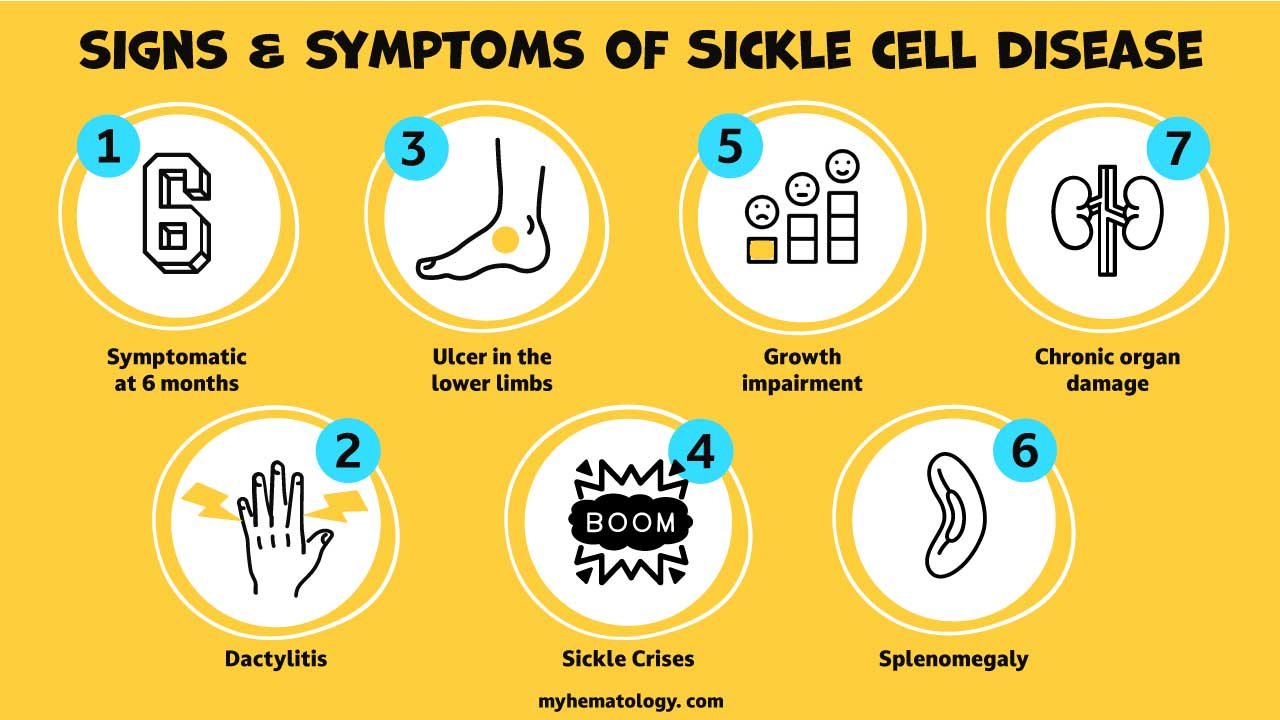

- Signs and symptoms ▾: Symptoms appear after 6 months of age when hemoglobin switching occurs. General signs of anemia is common with acute problems and growth impairment in children while chronic organ damage can be seen in adults.

- Confirmatory / Diagnostic tests ▾:

- Sickling test

- Hemoglobin electrophoresis

- High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)

- Positive DNA mutation test (PCR)

- Peripheral blood smear (screening)

- Treatment and management ▾:

- Prophylactic penicillin

- Pneumococcal and meningococcal vaccine

- Avoid dehydration, hypoxia and circulatory stasis

- Active treatment for bacterial infections

- Oral / IV fluids, analgesics, oxygen, exchange transfusion and ventilatory support during painful crises

- Transfusion when necessary

- Bone marrow transplantation

- Regular cerebral blood flow surveillance and prophylactic transfusions

- Hydroxyurea for adults

- Splenectomy in splenic sequestration crises

- Gene therapy

*Click ▾ for more information

What is the function of the red blood cell?

The main function of the red blood cell is to carry oxygen from the lungs to the tissues and then transport carbon dioxide back from the tissues to be expelled through the lungs. For the red blood cell to function, it depends on the red blood cell metabolism pathways, the membrane structure as well as the hemoglobin content. As the main function of the red blood cell is as an oxygen carrier, a mature erythrocyte is essentially a bag full of hemoglobins.

In a healthy adult, there are approximately 270 million hemoglobins in 1 red blood cell. The hemoglobin is a tetrameric structure of 2 alpha-like and 2 beta-like globin chains interconnected by specific points and each folded globin chain carries a heme peptide with an iron atom in the center. Each iron atom can carry 1 molecule of oxygen.

The alpha globin gene cluster is found on chromosome 16 while the beta globin gene cluster is found on chromosome 11. The genes in the cluster are arranged according to the order of development and at different stages of development, different hemoglobin subtypes are formed to have different oxygen affinities. For example, fetal hemoglobin or Hb F have a higher oxygen affinity compared to Hb A to allow for oxygen exchange between the mother and the developing fetus. However, Hb F switches to Hb A (at around 6 months after birth) which is more efficient in oxygen delivery once the baby is born.

What are hemoglobin disorders?

Disorders of the hemoglobin or hemoglobinopathies are mutations affecting the globin genes and are usually inherited. They can be loosely classified into structural hemoglobinopathies which is a qualitative disorder of the hemoglobin for example Hb S. In structural hemoglobinopathies, the hemoglobins formed are not able to carry oxygen as efficiently as the normal hemoglobins. The other group of hemoglobinopathy is thalassemia which is a quantitative reduction or absence of one or more of the globin chain production.

What is sickle cell anemia?

Sickle cell anemia is a hereditary chronic hemolytic anemia caused by the production of Hb S as a result of a mutation in codon 6 of the beta globin gene. This mutation causes the hemoglobin to sickle when the red cell is deoxygenated.

Epidemiology

Most frequent in Africa, Middle East and India. The sickle red cells confer some protective mechanism against malaria and has allowed this faulty gene to persist historically. Even just one copy of the sickle gene (sickle cell trait) is enough to offer some resistance towards malaria.

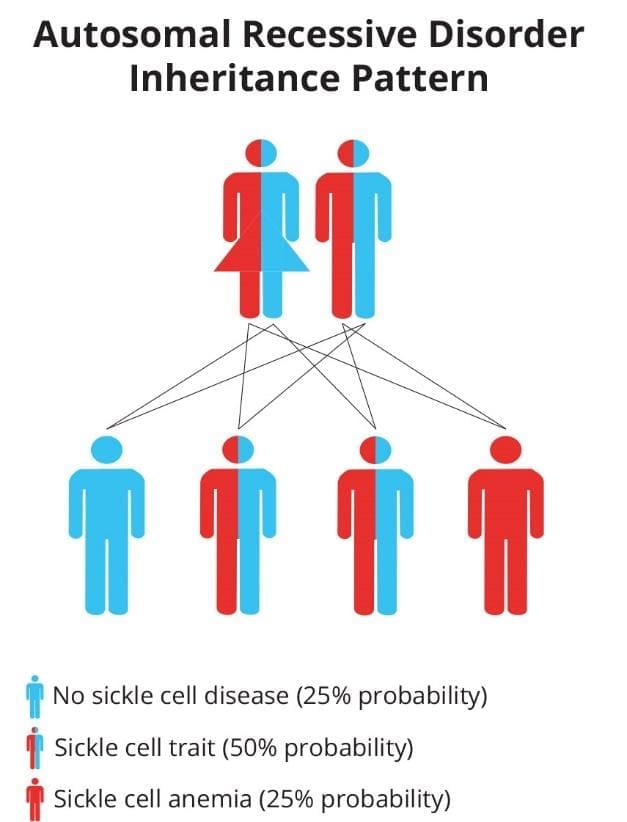

Inheritance pattern

Genetically speaking, hemoglobinopathies are mainly autosomal recessive disorders where we need two mutant alleles to be clinically symptomatic. Sickle cell trait or carriers are generally asymptomatic.

Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology of Sickle Cell Anemia

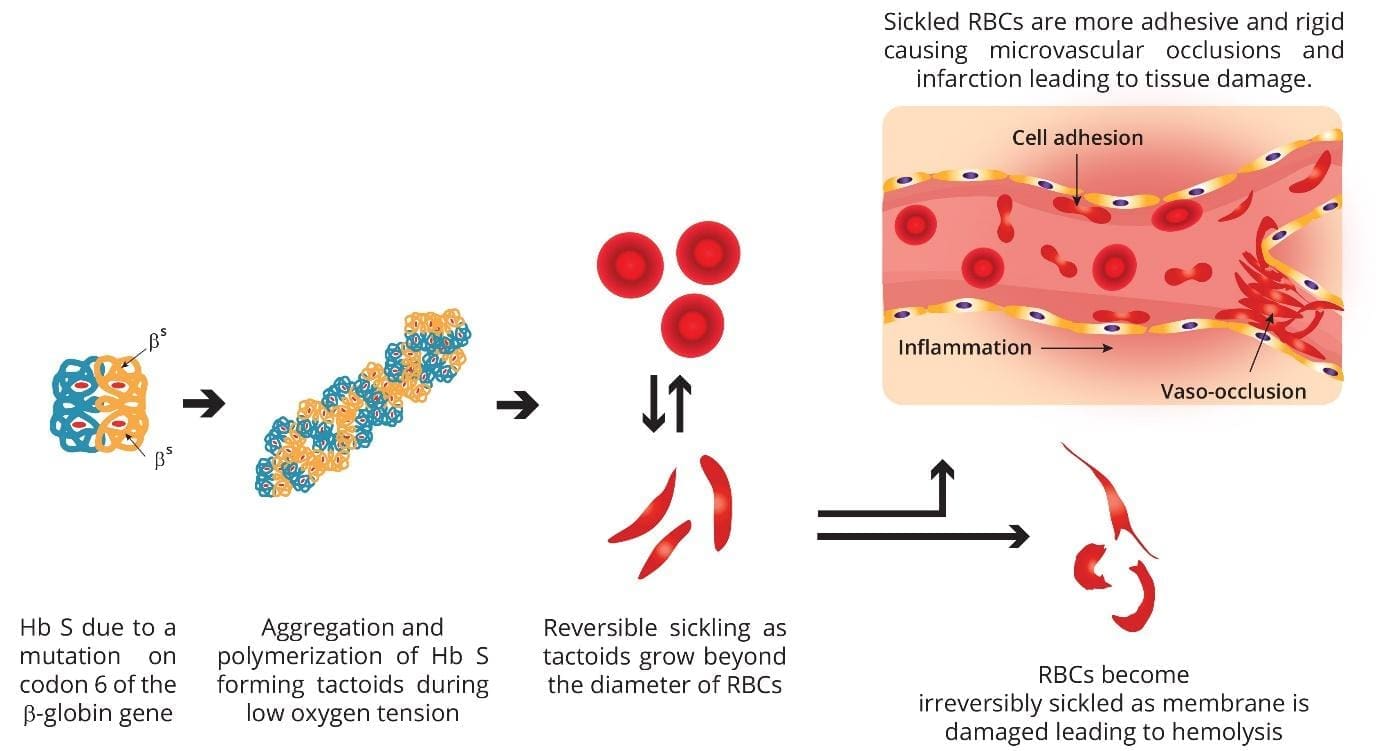

Sickle cell anemia is caused by a mutation in codon 6 of the beta globin gene, where the wild type glutamic acid (GAG) has been changed to valine (GTG) forming hemoglobin S. Hemoglobin S (Hb S) is insoluble and forms crystals when exposed to low oxygen tension. Deoxygenated sickle hemoglobins tend to clump and polymerize into long fibers called tactoids.

Initially, when the sickle hemoglobins clump together to form tactoids during the deoxygenation phase, the red blood cells are still reversibly sickled. But as more and more Hb S forms the long fibers, the red cells become irreversibly sickled and are unable to revert back to its biconcave shape. These red cell membranes are sticky and cause microvascular occlusions. They also cause vascular inflammation when they adhere to the vascular walls and in the spleen, there is a lot of hemolysis, congestion and infarction as these cells accumulate in the reticuloendothelial system to be destroyed. The disease is primarily characterized by two intertwined processes: Vaso-Occlusion and Chronic Hemolysis.

Vaso-Occlusion

Vaso-occlusion is the primary clinical manifestation and the cause of acute pain crises in SCA.

| Mechanism | Description |

| Microvascular Obstruction | The stiff, sickle-shaped RBCs lose their flexibility and cannot squeeze through narrow capillaries and post-capillary venules. They clump together, obstructing blood flow. |

| Adhesion and Inflammation | Sickle RBCs are abnormally “sticky” due to damage to their cell membrane, which exposes adhesion molecules (like α4β1). These molecules bind excessively to receptors (like VCAM-1, P-selectin) on the activated endothelium (the inner lining of blood vessels). This adhesion slows blood flow, promoting more deoxygenation and more sickling in a vicious cycle. |

| Ischemia and Pain | The blocked blood flow prevents oxygen from reaching tissues downstream (ischemia), leading to tissue damage (infarction) and the excruciating pain of a Vaso-Occlusive Episode (VOE), or pain crisis. |

Chronic Hemolysis

Chronic hemolysis refers to the premature and continuous destruction of red blood cells.

| Mechanism | Description |

| RBC Fragility | The repeated cycles of sickling (in the low oxygen tissues) and unsickling (in the high oxygen lungs) mechanically damage the RBC membrane. These fragile cells are then rapidly cleared by the spleen and liver. |

| Reduced Lifespan | Normal RBCs live for ~120 days. Sickled cells have a lifespan of only 10 to 20 days, resulting in a state of chronic anemia. The bone marrow struggles to compensate, leading to a high reticulocyte count. |

| Intravascular Hemolysis | Many sickled cells break down directly in the bloodstream. This releases cell-free hemoglobin and free heme, which are major drivers of chronic complications. |

Systemic Consequences (End-Organ Damage)

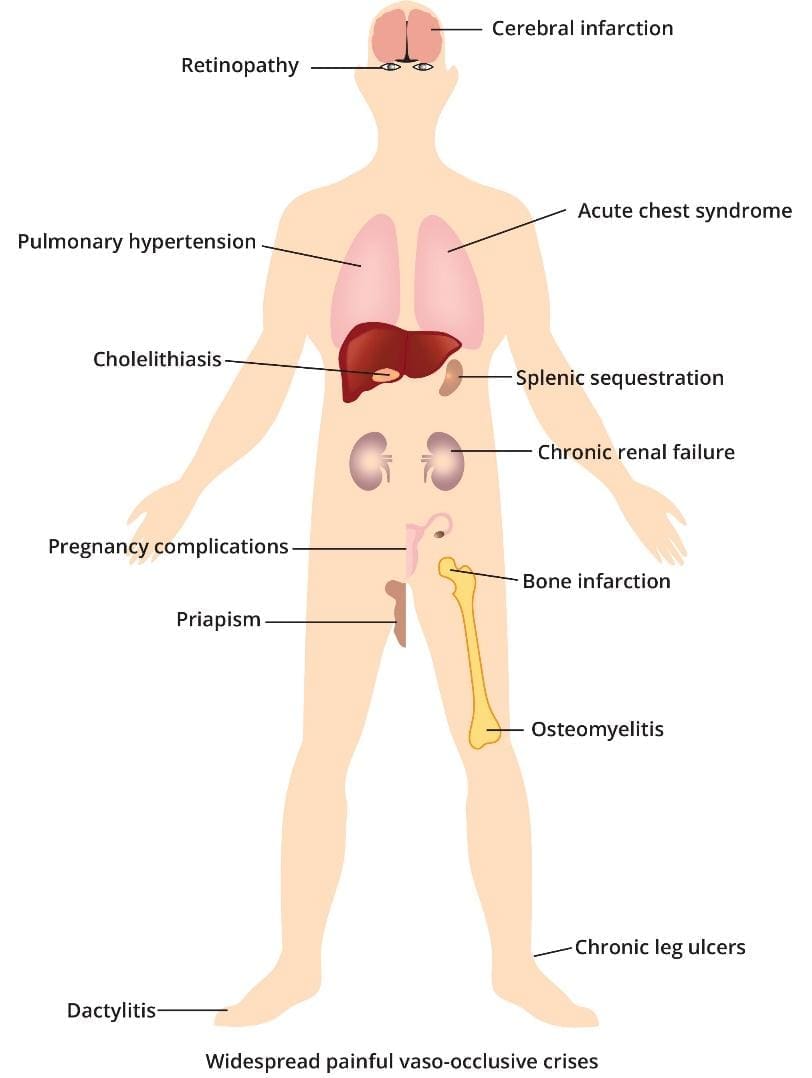

The two primary processes which are vaso-occlusion and chronic hemolysis, lead to widespread organ damage and systemic dysfunction.

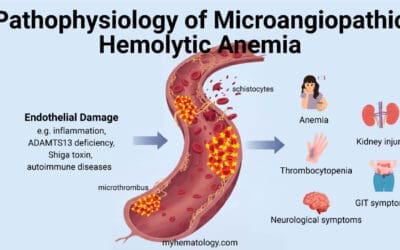

Endothelial Dysfunction and Vasculopathy

This is a central chronic problem exacerbated by cell-free hemoglobin. Free hemoglobin released during hemolysis binds to and scavenges Nitric Oxide (NO), a critical molecule that causes blood vessels to relax (vasodilation). Loss of NO leads to chronic vasoconstriction (narrowing of blood vessels) and high blood pressure, particularly in the lungs (Pulmonary Hypertension), which is a major cause of mortality.

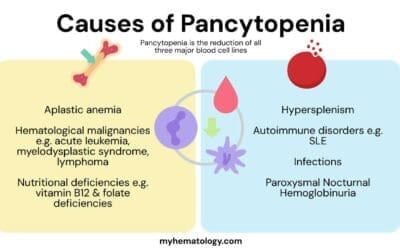

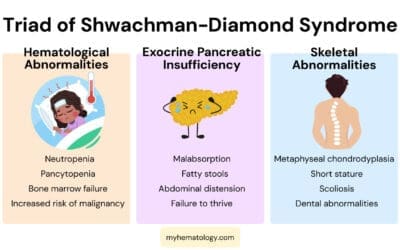

Functional Asplenia

The spleen’s job is to filter old or damaged blood cells. Due to the high volume of sickled cells, the spleen becomes repeatedly blocked and scarred (infarcted). By early childhood, the spleen is typically shrunken and non-functional, a state called autosplenectomy or functional asplenia. This loss of function results in a severe inability to fight encapsulated bacteria (like Streptococcus pneumoniae), leading to a high risk of life-threatening sepsis and infection.

Chronic Organ Damage

Repeated episodes of ischemia/reperfusion injury and chronic inflammation cause irreversible damage across the body.

- Stroke: Vaso-occlusion and chronic inflammation damage blood vessels in the brain.

- Acute Chest Syndrome (ACS): Blockage of vessels in the lungs, often triggered by infection or fat emboli from bone marrow, leading to chest pain, fever, and hypoxemia.

- Renal Disease: Damage to the small vessels in the kidneys (nephropathy).

- Avascular Necrosis (AVN): Bone tissue death, usually in the hip or shoulder joints, due to interrupted blood supply.

- Cholelithiasis (Gallstones): Chronic hemolysis leads to high levels of bilirubin (a breakdown product of heme), which precipitates to form gallstones

What are the signs and symptoms of sickle cell anemia?

The signs and symptoms of Sickle Cell Anemia (SCA) are highly variable among individuals and change over a lifetime. They are primarily driven by two pathological processes: chronic anemia due to red blood cell (RBC) destruction, and vaso-occlusion (blockage of small blood vessels) leading to tissue damage.

Symptoms typically begin to manifest around 5 or 6 months of age, as the protective Fetal Hemoglobin (HbF) is replaced by the abnormal Hemoglobin S (HbS).

Acute Symptoms and Complications (Sickle Cell Crises)

Acute episodes, often called Sickle Cell Crises or Vaso-Occlusive Episodes (VOE), are the most common reason for emergency care.

Vaso-Occlusive Crisis (VOC) or Pain Crisis

Vaso-occlusive crisis is the hallmark of SCA, caused by sickled cells blocking blood flow to tissues (ischemia).

- Pain: Sudden, severe pain that can be dull, throbbing, or stabbing. It is most common in the bones (especially the back, chest, arms, and legs) and joints. It can last hours to weeks.

- Dactylitis (Hand-Foot Syndrome): Painful swelling of the hands and feet, often the first symptom of SCA in infants and toddlers.

Acute Chest Syndrome (ACS)

A life-threatening complication that resembles pneumonia, often triggered by infection or fat emboli from the bone marrow.

- Signs: Chest pain, fever, cough, and shortness of breath (dyspnea). Multiple episodes can lead to permanent lung damage.

Splenic Sequestration Crisis

Occurs most commonly in young children (under age 5) before the spleen is fully scarred (autosplenectomy).

- Mechanism: Sickled cells become trapped in the spleen, causing it to swell dramatically.

- Signs: Sudden, painful enlargement of the spleen, marked abdominal pain, rapid drop in hemoglobin, pallor, and signs of shock (rapid heart rate, fast breathing). This is a medical emergency.

Aplastic Crisis

A transient halt in RBC production by the bone marrow, usually triggered by infection (most commonly Parvovirus B19).

- Signs: Profoundly worsened anemia, paleness, and extreme fatigue due as the body cannot replace the rapidly destroyed sickled cells.

Stroke

Sickled cells blocking blood flow to the brain can cause an ischemic stroke, most common in children between 2 and 9 years old.

- Signs: Sudden weakness or paralysis (hemiplegia), slurred speech, facial drooping, confusion, or severe headache.

Chronic Symptoms and Signs

These signs are often present at baseline due to chronic hemolytic anemia (destruction of RBCs) and long-term organ damage.

Chronic Anemia and Jaundice

- Fatigue and Weakness: Due to the chronic shortage of healthy, oxygen-carrying RBCs (RBCs only live 10-20 days instead of 120).

- Pallor: Unusually pale skin and mucosal membranes.

- Jaundice: Yellowing of the skin and the whites of the eyes (sclerae), caused by high levels of bilirubin, a yellow pigment released when RBCs are broken down.

Infections and Immune Compromise

- Functional Asplenia: Repeated sickling leads to scarring and shrinking of the spleen, called autosplenectomy, by early childhood.

- Increased Risk: The non-functional spleen cannot filter encapsulated bacteria (like Streptococcus pneumoniae), making patients highly vulnerable to severe, life-threatening bacterial infections (sepsis, meningitis).

Chronic Organ Damage

Organ damage accumulates over years from repeated vaso-occlusion and chronic inflammation.

- Avascular Necrosis (AVN): Bone tissue death, most commonly affecting the hip and shoulder joints, causing chronic, debilitating joint pain.

- Leg Ulcers: Painful, non-healing sores on the lower legs, usually seen in adults, due to poor circulation.

- Priapism: A persistent, painful, and often prolonged erection in males, resulting from blockages in the penile blood vessels. This is an emergency that can lead to impotence if untreated.

- Pulmonary Hypertension (PH): High blood pressure in the arteries of the lungs, typically affecting adults, leading to shortness of breath and extreme fatigue.

- Kidney Damage: Impaired kidney function that can lead to chronic kidney disease.

| Stage of Life | Most Common Signs/Symptoms |

| Infancy/Early Childhood | Dactylitis (Hand-Foot Syndrome), Splenic Sequestration Crisis, High Risk of Sepsis/Infection. |

| School Age | Vaso-Occlusive Crises (Pain), Stroke, Chronic Anemia/Fatigue. |

| Adulthood | Chronic Pain, Avascular Necrosis (Joint Pain), Leg Ulcers, Pulmonary Hypertension, Organ Failure. |

How do I test for sickle cell anemia?

The investigation and diagnosis of Sickle Cell Anemia (SCA) rely on identifying the presence and quantity of Hemoglobin S (HbS) and differentiating various sickle cell genotypes (e.g., HbSS, HbSC, HbS-beta-thalassemia). The standard approach involves screening and definitive confirmatory testing.

Screening Tests

Screening tests are used to quickly determine the presence of HbS, especially in newborns.

- Newborn Screening (NBS): Mandatory in all US states and many other countries to diagnose SCA and other hemoglobinopathies early, allowing for immediate prophylactic care (e.g., penicillin) to prevent life-threatening infections. The main confirmatory tests (HPLC or IEF) are typically used for the initial screening in this setting.

- Hemoglobin Solubility Test (Sickle/Dithionite Test): A rapid, inexpensive test to screen for the presence of any HbS. It utilizes the principle that deoxygenated HbS is relatively insoluble in concentrated buffer solution, causing the solution to become cloudy (turbid) if HbS is present. This test cannot differentiate between Sickle Cell Disease (HbSS) and Sickle Cell Trait (HbAS), and it can be falsely negative in infants (due to high Fetal Hemoglobin, HbF) or in severely anemic patients. It is not recommended for definitive diagnosis.

Confirmatory Laboratory Tests

These are the definitive methods used to diagnose the specific type of hemoglobinopathy by separating and quantifying all hemoglobin fractions.

Hemoglobin Electrophoresis and HPLC

These are the gold standards for separating and quantifying different types of hemoglobin.

| Test | Mechanism | Utility in SCA Diagnosis |

| Hemoglobin Electrophoresis | Separates hemoglobin molecules based on their electrical charge as they migrate through a gel or liquid medium. | Historically used, but less precise for quantification than HPLC. It identifies the presence of HbS, HbA, HbF, and HbC. |

| High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) | Separates hemoglobin based on their chemical properties using a column and specialized liquid. | The preferred method. It provides accurate quantification of HbA, HbA2, HbF, and HbS, allowing for differentiation of genotypes: HbSS, HbAS, HbSC. |

Genetic Testing (DNA Analysis)

This test is used to confirm ambiguous results from protein-based testing, to distinguish between different forms of Sickle Cell Disease (e.g., HbS/beta-thalassemia vs. HbS/S), and for prenatal diagnosis by analyzing the HBB gene mutation on chromosome 11.

For Prenatal Diagnosis, this test is performed on cells obtained through Amniocentesis (sampling amniotic fluid) or Chorionic Villus Sampling (CVS) (sampling placental tissue) to determine the fetus’s genotype.

General Hematology and Clinical Monitoring

Routine blood work provides critical supportive evidence and is used to monitor the disease’s severity and response to treatment.

Complete Blood Count (CBC)

- Hemoglobin (Hb)/Hematocrit (Hct): Typically low (anemia) due to chronic hemolysis. The patient’s baseline is important for identifying acute drops.

- Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV): Often normal or slightly elevated, especially in patients taking Hydroxyurea.

- White Blood Cell (WBC) Count: Usually elevated due to chronic inflammation, even in the absence of acute infection.

- Platelet Count: Can be elevated.

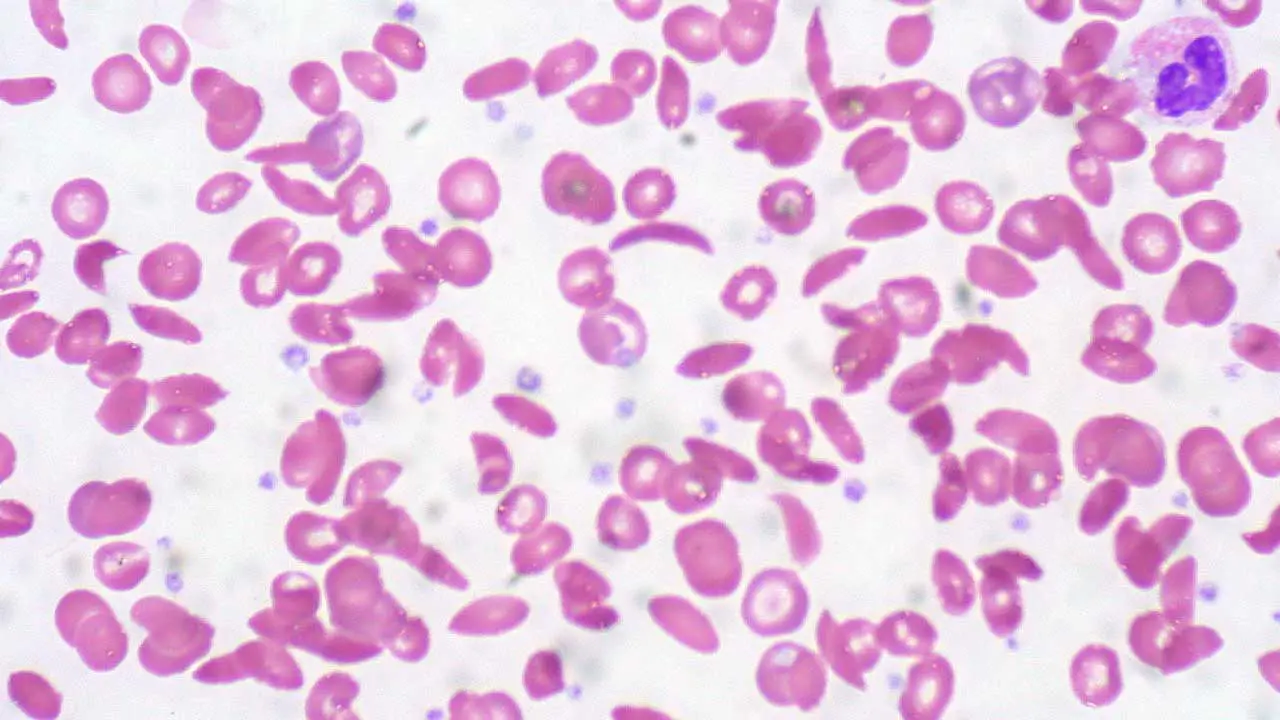

Peripheral Blood Smear (PBS)

A blood smear examined under a microscope can reveal the characteristic morphologic abnormalities. Sickled Erythrocytes are the hallmark where crescent or elongated shapes are seen, especially after blood is deoxygenated. Apart from that, there will be anisopoikilocytosis, target cells and Howell-Jolly bodies. Presence of Howell-Jolly bodies is a tell-tale sign of functional asplenia (non-working spleen), which is a crucial clinical finding in sickle cell anemia.

Reticulocyte Count

In chronic sickle cell anemia, the count is typically elevated as the bone marrow tries to compensate for the rapid destruction of sickled cells. It is critical for diagnosing acute crises:

- Aplastic Crisis: The reticulocyte count drops sharply (low/absent).

- Hemolytic Crisis: The reticulocyte count increases sharply (very high).

Transcranial Doppler (TCD) Ultrasonography

A key screening tool for a major complication: stroke risk in children. High velocity indicates turbulent flow and is a strong predictor of high stroke risk, prompting the initiation of prophylactic blood transfusions.

How is sickle cell anemia treated?

The treatment and management of Sickle Cell Anemia (SCA) are multifaceted, focusing on three main goals: prevention of acute crises, reduction of chronic organ damage, and curative therapies.

Prophylactic and Disease-Modifying Therapies

These treatments are used chronically to reduce the severity and frequency of disease manifestations.

Prophylactic Antibiotics and Immunizations

Due to functional asplenia (non-working spleen), patients are highly susceptible to encapsulated bacterial infections.

- Penicillin Prophylaxis: Given orally to children, typically from diagnosis (around 2 months) until at least age 5, to prevent life-threatening sepsis caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae.

- Immunizations: Patients must receive all routine childhood vaccines, plus additional vaccines, including the pneumococcal vaccine (PCV13 and PPSV23) and meningococcal vaccine.

Hydroxyurea (Hydroxycarbamide)

This is the most crucial disease-modifying therapy for children and adults with frequent crises or severe symptoms. Hydroxyurea works primarily by stimulating the production of Fetal Hemoglobin (HbF). HbF does not sickle, effectively “diluting” the Hemoglobin S (HbS) and reducing polymerization, thus decreasing red blood cell sickling. It also has anti-inflammatory effects. This treatment requires close monitoring of blood counts (CBC) as a common side effect is myelosuppression (low white cell count).

New Targeted Therapies (FDA-Approved)

Recent advances have introduced new classes of drugs that target specific steps in the sickling and vaso-occlusion process.

- Voxelotor (Oxbryta): An oral medication that works by directly increasing the affinity of hemoglobin for oxygen, which inhibits the polymerization of HbS and decreases sickling.

- Crizanlizumab (Adakveo): An intravenous (IV) monoclonal antibody that targets P-selectin, a protein on the surface of endothelial cells and platelets. By blocking P-selectin, it reduces the adhesion of sickled cells to the blood vessel walls, thereby reducing the frequency of Vaso-Occlusive Crises (VOCs).

- L-Glutamine (Endari): An oral powder that is thought to improve the health of red blood cells by reducing oxidative stress, leading to fewer complications.

Management of Acute Crises

Acute crises require rapid and specific treatment, often in the emergency department or hospital.

| Crisis | Primary Management Strategy |

| Vaso-Occlusive Crisis (VOC)/Pain | 1. Aggressive Analgesia: Immediate and scheduled administration of opioids (often via Patient-Controlled Analgesia (PCA)) and NSAIDs. 2. Hydration: Intravenous fluids to reverse dehydration and improve blood flow. 3. Oxygen: If the patient is hypoxemic. |

| Acute Chest Syndrome (ACS) | Requires rapid action: Oxygen, Broad-spectrum Antibiotics, Analgesia, and Transfusion. Exchange Blood Transfusion is often preferred to quickly lower the percentage of circulating HbS below 30% and improve oxygenation. |

| Severe Anemia or Stroke | Blood Transfusion: May be simple (packed RBCs) or exchange transfusion (removing sickled blood while replacing with healthy donor blood) for rapid reversal of severe symptoms or high-risk situations like stroke. |

| Infection/Fever | Empiric Antibiotics: Immediate administration of IV antibiotics, even before culture results are known, due to the high risk of life-threatening sepsis. |

Curative Therapies

Bone Marrow Transplant

This is the only curative option available, but it’s a complex procedure with significant risks. It involves replacing the patient’s bone marrow with healthy bone marrow from a matched donor. This approach is typically reserved for severe cases when other treatments are not effective or when a suitable gene therapy option is unavailable.

Gene Therapy

- Casgevy™ is a recently approved gene therapy that offers a potential cure. It uses CRISPR-Cas9 technology to edit a patient’s own blood stem cells to reactivate the fetal hemoglobin production, thus reducing the occurrence of vaso-occlusive crises.

- Lyfgenia™, also recently approved, uses a viral envelope to deliver a healthy hemoglobin-producing gene.

However, gene therapy comes with a heft price tag of USD $2 – 3 million each shot.

What are the complications of sickle cell anemia?

The complications of Sickle Cell Anemia (SCA) are broadly categorized into Acute Crises and Chronic Organ Damage, all stemming from chronic hemolysis and repeated vaso-occlusion.

Acute Sickle Cell Crises (Medical Emergencies)

Acute crises are sudden, severe events requiring urgent medical intervention.

Vaso-Occlusive Crisis (VOC) / Pain Crisis

- Mechanism: The most frequent crisis. Sickled cells block small blood vessels, causing tissue ischemia and infarction.

- Symptoms: Severe, acute pain in the limbs, back, chest, or abdomen.

- Management: Prompt and aggressive pain control (often using scheduled opioids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)), intravenous (IV) hydration, and addressing any underlying trigger (e.g., infection).

Acute Chest Syndrome (ACS)

- Mechanism: A life-threatening condition involving pulmonary infarction and/or infection, leading to hypoxemia.

- Symptoms: Fever, cough, chest pain, and new pulmonary infiltrate on chest X-ray.

- Management: Oxygen supplementation, antibiotics (to cover likely infection), aggressive pain control, bronchodilators, and often exchange blood transfusion (to rapidly lower the percentage of HbS) in severe cases.

Splenic Sequestration Crisis

- Mechanism: Most common in young children. Massive, sudden trapping of blood within the spleen, leading to acute, rapid splenic enlargement.

- Result: Rapid, life-threatening drop in hemoglobin, hypovolemia, and shock.

- Management: Immediate blood transfusion to stabilize hemoglobin and circulation. If recurrent, a splenectomy (surgical removal of the spleen) may be necessary.

Visceral Sequestration (e.g., Hepatic)

- Mechanism: Similar to splenic sequestration, but occurring in the liver or, rarely, other organs.

- Result: Acute, tender liver enlargement and rapid drop in hemoglobin.

- Management: Supportive care, IV fluids, and possible exchange transfusion if severe.

Aplastic Crisis

- Mechanism: A temporary halt in red blood cell production by the bone marrow, usually triggered by Parvovirus B19 infection.

- Result: Profound worsening of the chronic anemia, characterized by a critically low reticulocyte count (new RBC production stops).

- Management: Supportive care and red blood cell transfusion until the bone marrow recovers (usually 7–10 days).

Hemolytic Crisis

- Mechanism: An acute increase in the rate of red blood cell destruction (hemolysis). Less common than the above crises, often triggered by severe infection.

- Result: Rapid drop in hemoglobin with a rising reticulocyte count (the bone marrow is trying to compensate but cannot keep up).

- Management: Treating the underlying trigger and blood transfusion as needed.

Chronic Complications and Management Strategies

Chronic complications are irreversible forms of organ damage that develop over time from continuous vaso-occlusion and inflammation.

Cerebrovascular Complications (Stroke)

- Complication: Both ischemic stroke (blockage) and hemorrhagic stroke (bleeding) can occur.

- Chronic Management Strategy:

- Screening: Children aged 2–16 years should undergo annual Transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasonography to measure blood flow velocity in the brain.

- Chronic Transfusion Protocol: Patients identified as high-risk by TCD (high velocity) are placed on a regular chronic red blood cell transfusion program (typically every 3–4 weeks). The goal is to keep the percentage of circulating HbS below 30% to prevent new or recurrent stroke.

Pulmonary Hypertension (PH)

- Complication: Chronic damage to the lung’s blood vessels leads to high blood pressure in the pulmonary arteries, causing right-sided heart failure and shortness of breath.

- Chronic Management Strategy:

- Diagnosis is confirmed via echocardiogram and right heart catheterization.

- Management often involves specific vasodilating medications, such as Endothelin Receptor Antagonists (e.g., Bosentan) or Phosphodiesterase-5 Inhibitors (e.g., Sildenafil), to relax the pulmonary blood vessels.

Avascular Necrosis (AVN)

- Complication: Also called osteonecrosis. Interrupted blood supply to a section of bone, causing the bone tissue to die and collapse. It most commonly affects the femoral head (hip) and the humeral head (shoulder).

- Chronic Management Strategy:

- Early Stages: Rest, pain management, and physical therapy.

- Advanced Stages: Surgical intervention, such as core decompression (to relieve pressure) or total joint replacement (hip or shoulder arthroplasty), is often required.

Chronic Organ Damage

- Nephropathy (Kidney Disease): Chronic microvascular damage leads to proteinuria and progressive kidney failure.

- Management: Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitors and Angiotensin Receptor Blockers (ARBs) are used to protect the kidneys.

- Retinopathy: Sickling in the eye’s blood vessels can lead to detachment and blindness.

- Management: Regular eye exams and laser photocoagulation to treat abnormal vessel growth.

- Iron Overload (from Transfusions): Chronic transfusions cause excessive iron accumulation in the heart, liver, and endocrine glands.

- Management: Chelation Therapy (e.g., Deferoxamine, Deferasirox) is required to remove the excess iron.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Can sickle cell anemia be cured?

Currently, there is no cure for sickle cell anemia. However, there are effective treatment options that can significantly improve the lives of people with the disease. These treatments focus on managing symptoms, preventing complications, and potentially offering a chance for a cure in some cases.

Can sickle cell patient live long?

Sickle cell disease (SCD) can significantly impact life expectancy, but advancements in treatment have improved the outlook for patients.

Life Expectancy

- Traditionally, the average life expectancy for individuals with SCD was lower than the general population.

- Recent studies indicate some improvement, with the national median life expectancy in the US for publicly insured individuals with SCD at around 52.6 years (compared to the national average of 73.5 years for men and 79.3 years for women).

Factors Affecting Life Expectancy

- Severity of SCD: The specific type of SCD and the proportion of abnormal red blood cells can influence life expectancy. More severe forms with frequent complications generally have a lower life expectancy.

- Access to healthcare: Early diagnosis, comprehensive treatment, and good management of complications are crucial for maximizing life expectancy.

- Lifestyle factors: Maintaining a healthy lifestyle with proper hydration, a balanced diet, regular exercise (as tolerated), and avoiding smoking can significantly improve overall health and potentially lengthen lifespan.

What can trigger sickle cell crisis?

Sickle cell crisis occurs when the abnormal, sickle-shaped red blood cells clump together and block blood flow in small blood vessels. This blockage can cause pain, tissue damage, and a variety of complications. Several factors can trigger a sickle cell crisis, although the exact cause may not be identifiable in every instance. Here are some of the most common triggers:

- Infection: People with SCD are more susceptible to infections, and even minor infections can trigger a crisis.

- Dehydration: Not drinking enough fluids can thicken the blood and make it easier for sickle cells to clump.

- Pain: Pain itself can trigger a crisis, creating a vicious cycle.

- Stress: Physical or emotional stress can activate the body’s fight-or-flight response, leading to physiological changes that promote sickling.

- Sudden temperature changes: From hot to cold or vice versa can trigger a crisis.

- Low oxygen levels: This can occur at high altitudes or during strenuous exercise.

- Deoxygenation: Sickle cells are more prone to sickling when they’re not carrying oxygen. This can happen during sleep or anesthesia.

- Certain medications: Some medications can worsen sickling or interfere with other treatments. Discussing all medications with your doctor is crucial.

- Puberty and menstruation: Hormonal changes during these times might increase the risk of crises for some individuals.

It’s important to note that:

- Triggers can vary from person to person. Some people might have specific triggers they can identify, while others may experience crises without an obvious cause.

- Avoiding triggers whenever possible can help reduce the frequency and severity of crises.

Who is most at risk for sickle cell anemia?

People with a family history of sickle cell disease are most at risk for inheriting the condition.

- Genetic Inheritance: Sickle cell anemia is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder. This means a person needs to inherit two copies of the abnormal sickle cell gene, one from each parent. Inheriting only a single copy of the mutation leads to sickle cell trait.

- Ancestral Background: The sickle cell gene mutation is more common in people with ancestry from regions where malaria was historically prevalent. These regions include:

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- South Asia (India, Saudi Arabia)

- Mediterranean countries (Greece, Turkey, Italy)

- Hispanic populations in Central and South America

What is the difference between thalassemia and sickle cell anemia?

Both thalassemia and sickle cell anemia are inherited blood disorders that affect red blood cells, but they have distinct causes and effects.

| Feature | Thalassemia | Sickle Cell Anemia |

|---|---|---|

| Cause | Reduced hemoglobin production | Abnormal hemoglobin S (HbS) production |

| Genetic Defect | Mutation in alpha or beta globin genes | Mutation in beta globin gene |

| Red Blood Cells | Reduced number, may be slightly abnormal shape | Normal number, sickle-shaped when deoxygenated |

| Symptoms | Fatigue, weakness, pale skin, slow growth (severe) | Painful crises, tissue damage, increased infection risk |

| Complications | Enlarged spleen, bone deformities (less common) | Organ damage (lungs, spleen, liver, etc.) |

Is sickle cell painful?

Yes, sickle cell anemia is a very painful condition. Pain is one of the most common and distressing symptoms of sickle cell disease.

Here’s a breakdown of the pain in sickle cell anemia:

- Cause: The abnormal, sickle-shaped red blood cells can get stuck in small blood vessels, blocking blood flow and causing tissue oxygen deprivation. This lack of oxygen triggers pain signals.

- Painful Episodes (Crises): These are the hallmark of sickle cell disease and can occur unpredictably. They can last for hours, days, or even weeks.

- Location of Pain: Pain can occur anywhere in the body, but commonly affects the

- Chest

- Back

- Abdomen

- Arms and legs

- Joints

- Severity of Pain: Pain can vary from mild to severe and can be debilitating. Some people describe it as a constant dull ache, while others experience excruciating pain.

Additional factors contributing to pain

- Inflammation: The body’s response to the damaged and blocked blood vessels can further contribute to pain.

- Nerve damage: Chronic pain episodes can damage nerves, leading to increased pain sensitivity.

Why is iron not good for sickle cell patients?

Iron is not inherently bad for people with sickle cell disease, but excess iron due to transfusions and potential absorption issues can be detrimental. Excess iron acts like a toxin in the body, damaging organs like the liver, heart, and pancreas. This damage can lead to serious complications like liver fibrosis and cirrhosis, heart failure and diabetes. Careful management through chelation therapy, monitoring, and potentially dietary adjustments is crucial to prevent iron overload and its associated complications.

What are the first signs of sickle cell crisis?

The initial signs of a sickle cell crisis can vary depending on the individual and the type of crisis, but some common early indicators include:

- Pain: This is often the first and most prominent symptom. Pain can develop gradually or come on suddenly, and can occur anywhere in the body, although it frequently affects the:

- Chest (acute chest syndrome)

- Back

- Abdomen

- Arms and legs

- Joints

- Fatigue: Feeling unusually tired or sluggish can be an early sign, especially if accompanied by other symptoms.

- Shortness of breath: This can occur due to blocked blood flow to the lungs (acute chest syndrome) or simply due to fatigue.

- Fever: A low-grade fever can be an early indicator, but high fevers may also occur during a full-blown crisis.

- Headache: This is a common symptom, especially during a vaso-occlusive crisis (painful blockage of blood vessels).

What to do if you experience early signs of a crisis

- Rest: Take it easy and avoid strenuous activity.

- Hydration: Drink plenty of fluids to help thin your blood and improve circulation.

- Pain management: If you have pain medication prescribed by your doctor, take it as directed. However, don’t hesitate to seek medical attention, especially if the pain is severe or worsens.

- Warm or cold therapy: Applying a heating pad or cold compress to the affected area might provide some pain relief.

- Early intervention: Seeking medical attention at the first sign of a crisis can help prevent it from worsening and potentially reduce the duration and severity of the episode.

Does sickle cell get worse with age?

Yes, sickle cell disease (SCD) can worsen with age, but the progression and severity can vary depending on several factors.

Increased Complications

- As people with SCD age, they are more likely to experience complications from the disease. These complications arise due to chronic damage caused by repeated episodes of blocked blood vessels and hemolysis (destruction of red blood cells). Some common complications include:

- Organ damage: Organs like the lungs, liver, heart, kidneys, and spleen can be progressively damaged by recurrent sickling crises.

- Chronic pain: Frequent episodes of pain can become more chronic and debilitating over time.

- Increased risk of infections: Damage to the spleen and compromised immune function can make individuals with SCD more susceptible to infections.

- Pulmonary complications: Acute chest syndrome (blocked blood flow to the lungs) can become more frequent and severe with age.

- Stroke: Sickling can block blood flow to the brain, increasing the risk of stroke.

Cumulative Effects

- The longer someone lives with SCD, the greater the cumulative effect of the disease on their body. Tissue damage from repeated blockages and hemolysis can progressively worsen over time.

Does sickle cell cause blood clots?

Yes, people with sickle cell disease (SCD) are at a greater risk for developing blood clots compared to the general population because of:

- Sickled Red Blood Cells: The abnormal, crescent-shaped red blood cells in SCD are less flexible and more prone to clumping together. These clumps can block blood flow in small blood vessels, creating an environment conducive to clot formation.

- Chronic Inflammation: SCD is associated with chronic inflammation throughout the body. This inflammatory state can further contribute to blood clotting.

- Damaged Blood Vessel Walls: Repeated episodes of blocked blood flow can damage the inner lining of blood vessels, making them more susceptible to clot formation.

Does sickle cell compromise the immune system?

People with SCD are more prone to infections due to the weakened immune system. This is especially true for certain types of infections, such as those caused by bacteria encapsulated by a polysaccharide coat (e.g., Streptococcus pneumoniae). However, the hyperinflammatory response can also contribute to complications like vasoocclusive crises (painful episodes due to blocked blood flow).

Are sickle cell patients immune to malaria?

No, sickle cell disease (SCD) does not provide immunity to malaria. In fact, the relationship between SCD and malaria is complex and depends on the type of SCD a person has:

- Sickle cell trait: Offers some protection against malaria, especially the severe form.

- Sickle cell disease: Does not provide immunity and may increase the risk of severe complications from malaria.

How does sickle cell lead to death?

Sickle cell disease (SCD) can lead to death through various complications arising from the abnormally shaped red blood cells. Here’s a breakdown of the main causes:

Organ Damage

- Sickled red blood cells are rigid and sticky, causing them to get lodged in small blood vessels. This blockage can lead to:

- Organ damage: Over time, chronic blockage of blood flow can damage organs like the lungs, heart, kidneys, liver, and spleen. This damage can eventually lead to organ failure, which can be life-threatening.

- Acute chest syndrome (ACS): This complication arises when sickled red blood cells block blood vessels in the lungs, causing difficulty breathing, chest pain, and fever.

Infections

- People with SCD are more susceptible to infections due to a compromised immune system. This can be caused by:

- Damaged spleen: The spleen plays a vital role in filtering out bacteria from the bloodstream. In SCD, chronic damage to the spleen weakens its ability to fight infections.

- Reduced red blood cell production: Sickling and destruction of red blood cells can limit the body’s ability to produce enough healthy red blood cells, which can also carry oxygen-carrying proteins crucial for immune cell function.

- Severe infections, particularly those affecting the lungs (pneumonia) or bloodstream (sepsis), can be life-threatening in individuals with SCD.

Other Complications

- Pulmonary embolism: A blood clot that breaks loose and travels to the lungs, blocking blood flow and potentially leading to death.

- Stroke: Blocked blood flow to the brain can cause a stroke, leading to permanent neurological damage or death.

- Splenic sequestration: A large number of sickled red blood cells get trapped in the spleen, causing it to enlarge and potentially rupture, which can be a medical emergency.

Glossary of Medical Terms

- Hemoglobinopathy: A group of inherited disorders characterized by abnormal structure or production of the hemoglobin molecule (e.g., Sickle Cell Disease and Thalassemia).

- Hemoglobin S (HbS): The abnormal hemoglobin molecule formed due to the single-point mutation, which polymerizes and causes red blood cells to sickle when deoxygenated.

- Vaso-Occlusion: The blockage of a small blood vessel by rigid, sickled red blood cells, leading to ischemia (lack of blood supply) and subsequent tissue damage and pain.

- Vaso-Occlusive Crisis (VOC): The most common acute complication of SCA, characterized by sudden, severe pain resulting from vaso-occlusion in the microvasculature.

- Chronic Hemolysis: The continuous, premature destruction (lysis) of sickled red blood cells, which causes chronic anemia and releases breakdown products like bilirubin into the bloodstream.

- Autosplenectomy: The functional loss of the spleen due to repeated infarctions (blockages) caused by sickled cells, typically occurring early in life. This leaves the patient highly susceptible to infection.

- Dactylitis (Hand-Foot Syndrome): A painful inflammation and swelling of the hands and feet, often one of the first clinical manifestations of SCA in infants and toddlers.

- Acute Chest Syndrome (ACS): A severe, life-threatening complication characterized by new lung infiltrates on X-ray, fever, and respiratory symptoms, often requiring urgent transfusion.

- Priapism: A prolonged, painful, and unwanted erection that is not related to sexual stimulation, resulting from vaso-occlusion in the penile blood vessels.

- Avascular Necrosis (AVN): Also called osteonecrosis; the death of bone tissue, most commonly in the hip or shoulder, due to interruption of the blood supply.

- Chelation Therapy: Medical treatment using drugs called chelators to remove excess iron from the body, typically administered to patients who receive frequent blood transfusions.

- Fetal Hemoglobin (HbF): The type of hemoglobin produced during fetal development. Its production can be pharmacologically stimulated (e.g., by Hydroxyurea) to dilute HbS and reduce sickling.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Ashley-Koch A, Yang Q, Olney RS. Sickle hemoglobin (HbS) allele and sickle cell disease: a HuGE review. Am J Epidemiol. 2000 May 1;151(9):839-45. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010288. PMID: 10791557.

- Schnog JB, Duits AJ, Muskiet FA, ten Cate H, Rojer RA, Brandjes DP. Sickle cell disease; a general overview. Neth J Med. 2004 Nov;62(10):364-74. PMID: 15683091.

- Aliyu ZY, Tumblin AR, Kato GJ. Current therapy of sickle cell disease. Haematologica. 2006 Jan;91(1):7-10. PMID: 16434364; PMCID: PMC2204144.

- Cisneros GS, Thein SL. Recent Advances in the Treatment of Sickle Cell Disease. Front. Physiol., Sec. Red Blood Cell Physiology Volume 11 – 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2020.00435

- Williams TN, Thein SL. Sickle Cell Anemia and Its Phenotypes. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2018 Aug 31;19:113-147. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-083117-021320. Epub 2018 Apr 11. PMID: 29641911; PMCID: PMC7613509.

- Steinberg MH, Forget BG, Higgs DR, Weatherall DJ. Disorders of Hemoglobin: Genetics, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Management (Cambridge Medicine) 2nd Edition. 2009.

- Bain, B.J. (2017). A beginner’s guide to blood cells. Wiley Blackwell.

- Goldberg S, Hoffman J. Clinical Hematology Made Ridiculously Simple, 1st Edition: An Incredibly Easy Way to Learn for Medical, Nursing, PA Students, and General Practitioners (MedMaster Medical Books). 2021.

- https://www.yalemedicine.org/news/gene-therapies-sickle-cell-disease