TL;DR

Hydrops fetalis is excessive fluid accumulation in at least two fetal compartments (skin edema, pleural/pericardial effusion, ascites).

- Types: Immune (IHF, rare due to RhIG) and Non-Immune (NIHF, ~90% of cases).

- Pathophysiology ▾: Imbalance in fluid homeostasis, often due to increased hydrostatic pressure (heart failure), decreased oncotic pressure, lymphatic obstruction, or increased capillary permeability.

- Causes ▾: Diverse, including cardiac defects (most common NIHF), chromosomal anomalies, severe anemia (e.g., alpha-thalassemia, Parvovirus B19), infections (TORCH), and structural abnormalities.

- Presentation ▾: Primarily diagnosed by ultrasound (fluid in ≥2 compartments), may present postnatally with generalized edema and respiratory distress.

- Diagnosis ▾: Comprehensive workup includes maternal blood tests (alloantibodies, infections), detailed fetal ultrasound/echo, and often invasive procedures (amniocentesis, cordocentesis) for fetal genetic/infectious analysis.

- Treatment ▾: Cause-specific and supportive management.

- Prognosis ▾: Highly variable, dependent on underlying cause and gestational age; generally guarded, but improving with advancements.

*Click ▾ for more information

Introduction

Hydrops fetalis is a serious, life-threatening condition in a fetus or newborn characterized by the excessive accumulation of fluid in at least two different body compartments. These compartments typically include:

- Skin edema (swelling of the skin, often generalized or anasarca)

- Pleural effusion (fluid around the lungs)

- Pericardial effusion (fluid around the heart)

- Ascites (fluid in the abdominal cavity)

It’s not a disease itself, but rather a symptom or a final common pathway of a wide variety of underlying fetal disorders.

Understanding hydrops fetalis is crucial across obstetrics, neonatology, and pediatrics due to its profound impact on fetal and neonatal health, often necessitating urgent, multidisciplinary care.

Pathophysiology of Hydrops Fetalis

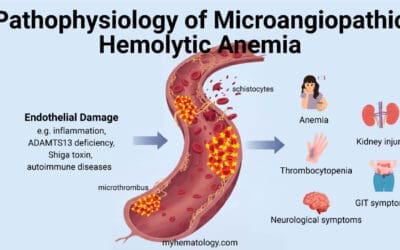

The pathophysiology of hydrops fetalis revolves around a critical imbalance in fetal fluid homeostasis, where the rate of fluid production in the interstitial spaces exceeds the capacity of the lymphatic system to drain it back into circulation. This leads to the abnormal accumulation of fluid in various fetal compartments. Several key mechanisms contribute to this imbalance.

These mechanisms often do not act in isolation. For instance, severe fetal anemia (e.g., due to Rh alloimmunization or alpha-thalassemia major) is a classic example that can trigger multiple pathophysiological pathways.

It directly leads to high-output cardiac failure as the heart tries to compensate for reduced oxygen-carrying capacity, increasing hydrostatic pressure.

The increased demand for red blood cell production can lead to extramedullary hematopoiesis in the liver, causing liver dysfunction and subsequently decreased albumin production and oncotic pressure.

Mechanisms Involved in Hydrops Fetalis

Increased Capillary Hydrostatic Pressure

This is a very common contributing factor, often stemming from fetal heart failure.

When the fetal heart is unable to pump blood effectively (e.g., due to structural defects, severe arrhythmias like supraventricular tachycardia, or myocardial dysfunction), it experiences increased pressures within the blood vessels.

This elevated pressure forces fluid out of the capillaries and into the interstitial spaces, leading to edema and effusions. Conditions causing high-output cardiac failure, such as severe anemia (where the heart works harder to deliver oxygen), large arteriovenous malformations, or significant fetal tumors (like sacrococcygeal teratomas which act as large shunts), also fall under this mechanism.

Decreased Plasma Oncotic Pressure

Plasma oncotic pressure, primarily maintained by albumin, is crucial for drawing fluid back into the capillaries. A decrease in plasma oncotic pressure means less fluid is retained within the blood vessels, leading to fluid leakage into the extravascular spaces.

This can occur due to:

- Severe protein loss: As seen in congenital nephrotic syndrome, where proteins are lost in urine.

- Impaired hepatic (liver) function: The liver is responsible for producing albumin. Conditions like severe fetal anemia (which can cause liver dysfunction due to extramedullary hematopoiesis) or certain congenital infections (e.g., severe parvovirus B19 infection) can impair liver function and reduce albumin synthesis.

Obstructed Lymphatic Drainage

The lymphatic system is designed to collect excess interstitial fluid and return it to the venous circulation. Any obstruction or malformation of the lymphatic system can lead to fluid accumulation. Examples include:

- Congenital lymphatic malformations: Such as cystic hygromas, which are often found in association with chromosomal anomalies like Turner syndrome.

- Thoracic masses or malformations: Like congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation (CCAM) or diaphragmatic hernia, which can compress major lymphatic vessels and impair drainage from the lungs and chest.

- Primary lymphatic dysplasia: Inborn errors affecting lymphatic development.

Increased Capillary Permeability

In certain conditions, the integrity of the capillary walls is compromised, allowing fluid and even proteins to leak out more easily. This can be caused by:

- Severe hypoxia/anoxia: Prolonged oxygen deprivation can damage endothelial cells.

- Inflammatory processes: Associated with certain congenital infections (e.g., parvovirus B19, CMV) that can cause direct damage to capillaries or induce a systemic inflammatory response.

Causes of Hydrops Fetalis

The causes of hydrops fetalis are remarkably diverse, reflecting the complexity of fetal development and physiology. They are broadly categorized into two main types: Immune Hydrops Fetalis (IHF) and Non-Immune Hydrops Fetalis (NIHF).

Immune Hydrops Fetalis (IHF)

Historically, this was the predominant cause, but its incidence has significantly declined due to prophylactic administration of Rho(D) immune globulin. IHF occurs when there’s an alloimmunization between the mother and the fetus, leading to the mother’s immune system attacking the fetus’s red blood cells.

- Rh Alloimmunization (Rh Disease): This is the classic cause. If an Rh-negative mother is exposed to Rh-positive fetal blood (e.g., during a previous pregnancy, miscarriage, abortion, or trauma), her immune system can develop antibodies against the Rh factor. In a subsequent pregnancy with an Rh-positive fetus, these maternal antibodies cross the placenta, bind to the fetal Rh-positive red blood cells, and cause their destruction (hemolysis). This leads to severe fetal anemia, which triggers high-output cardiac failure and ultimately hydrops.

- Other Red Blood Cell Alloimmunizations: While less common than Rh, other blood group incompatibilities (e.g., anti-Kell, anti-Duffy, anti-Kidd, anti-MNSs) can also lead to fetal hemolysis and immune hydrops through a similar mechanism.

Non-Immune Hydrops Fetalis (NIHF)

This category accounts for the vast majority (around 90%) of current hydrops cases and encompasses a wide spectrum of disorders that disrupt fetal fluid balance. NIHF can be due to problems with the heart, lungs, blood, chromosomes, or infections, among many others.

Cardiovascular Causes (Most common NIHF cause)

- Structural Heart Defects: Major congenital heart defects (e.g., hypoplastic left heart syndrome, atrioventricular septal defects, coarctation of the aorta) can impair cardiac function, leading to increased hydrostatic pressure and heart failure.

- Arrhythmias: Persistent fetal tachyarrhythmias (e.g., supraventricular tachycardia, atrial flutter) or bradyarrhythmias (e.g., complete heart block) can cause cardiac dysfunction and lead to hydrops.

- Myocardial Dysfunction: Conditions like myocarditis (inflammation of the heart muscle, often infectious), cardiomyopathy, or specific metabolic storage diseases affecting the heart.

- Cardiac Tumors: Rare, but tumors like rhabdomyomas can obstruct blood flow.

- Vascular Malformations: Large arteriovenous malformations (e.g., vein of Galen aneurysm) can act as significant shunts, leading to high-output cardiac failure.

Chromosomal Abnormalities

- Turner Syndrome (45,X): Often associated with widespread lymphatic abnormalities (e.g., cystic hygromas) and cardiac defects, leading to hydrops.

- Trisomies (e.g., Trisomy 21 [Down Syndrome], Trisomy 18 [Edwards Syndrome], Trisomy 13 [Patau Syndrome]): These are frequently associated with cardiac anomalies, lymphatic defects, or other systemic issues that can culminate in hydrops.

- Triploidy: A lethal condition with an extra set of chromosomes, commonly associated with severe hydrops.

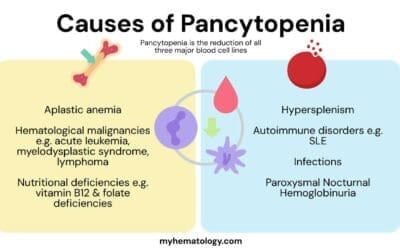

Hematologic Disorders

- Alpha-Thalassemia Major (Hb Barts Hydrops Fetalis): Particularly prevalent in Southeast Asia, this severe genetic disorder involves the complete absence of alpha-globin chain synthesis, leading to severe fetal anemia, hypoxemia, and ultimately high-output cardiac failure and hydrops.

- Severe Fetal Anemia (Non-Immune):

- Fetomaternal Hemorrhage: Significant bleeding from the fetal circulation into the maternal circulation.

- Twin-Twin Transfusion Syndrome (TTTS): In monochorionic twin pregnancies, one twin (the recipient) can become fluid overloaded and hydropic due to preferential blood flow from the co-twin.

- G6PD Deficiency or other Red Blood Cell Enzyme/Membrane Defects: Though rarer, these can cause severe hemolytic anemia.

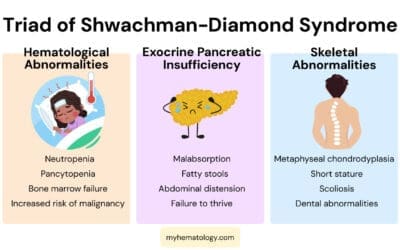

- Diamond-Blackfan Anemia or other inherited bone marrow failure syndromes.

Infections (TORCH and others)

Infections play a significant role in causing complications during pregnancy, including hydrops fetalis. The term TORCH is an acronym used in medicine to refer to a group of congenital (present at birth) infections that can be transmitted from a pregnant mother to her fetus, often with severe consequences for the developing baby.

- T – Toxoplasmosis: This is caused by the parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Pregnant women can contract it from eating undercooked meat, contaminated food/water, or exposure to cat feces. If transmitted to the fetus, it can lead to chorioretinitis (inflammation of the retina), hydrocephalus (fluid in the brain), intracranial calcifications, and developmental delays.

- O – Other: This category is a crucial placeholder for a variety of other significant infections that can cause congenital problems. While the specific list can sometimes vary, it commonly includes:

- Syphilis: A bacterial sexually transmitted infection (Treponema pallidum). Congenital syphilis can lead to stillbirth, prematurity, bone abnormalities, skin rashes, hepatosplenomegaly (enlarged liver and spleen), and neurological issues.

- Parvovirus B19 (Fifth Disease): This virus is a relatively common cause of non-immune hydrops fetalis. It targets red blood cell precursors, leading to severe fetal anemia, which can then cause high-output cardiac failure and widespread fluid accumulation.

- Varicella-Zoster Virus (Chickenpox): If a mother contracts chickenpox during early pregnancy, it can lead to congenital varicella syndrome, characterized by skin scarring, limb hypoplasia, microcephaly, and eye abnormalities.

- HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus): While not typically a direct cause of hydrops, HIV infection in the mother can be transmitted to the fetus, leading to various complications if untreated.

- Zika Virus: More recently recognized as a TORCH-like agent, particularly known for causing microcephaly and other severe brain abnormalities.

- Hepatitis B: Can be transmitted from mother to baby, leading to chronic infection in the infant.

- R – Rubella (German Measles): Caused by the rubella virus, this infection is particularly dangerous if contracted in the first trimester. It can lead to Congenital Rubella Syndrome (CRS), characterized by classic triad of cataracts, cardiac defects (e.g., patent ductus arteriosus, pulmonary artery stenosis), and sensorineural hearing loss, along with microcephaly and developmental delay. Due to widespread vaccination (MMR vaccine), congenital rubella is now rare in many developed countries.

- C – Cytomegalovirus (CMV): A common herpesvirus, CMV is the most frequent viral cause of congenital infection. While many infected newborns are asymptomatic, congenital CMV can cause sensorineural hearing loss (the most common long-term sequela), microcephaly, intracranial calcifications, hepatosplenomegaly, and developmental delays.

- H – Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV): This virus (HSV-1 or HSV-2) is usually transmitted to the newborn during vaginal delivery if the mother has active genital lesions. Neonatal herpes is a severe and potentially life-threatening infection that can cause skin, eye, and mouth lesions, encephalitis (brain inflammation), or disseminated disease affecting multiple organs.

Thoracic/Pulmonary Causes

- Congenital Cystic Adenomatoid Malformation (CCAM) / Congenital Pulmonary Airway Malformation (CPAM): Large lung lesions that can compress the heart or mediastinal vessels, impairing venous return and leading to hydrops.

- Bronchial Atresia or other Airway Obstructions: Can lead to fluid accumulation in the lung (hydrops of the lung).

- Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia: Can compress the heart and lungs, leading to heart failure.

- Primary Pleural Effusions (Chylothorax): Accumulation of lymphatic fluid in the chest due to lymphatic malformations, directly compressing the lungs and heart.

Urinary Tract Abnormalities

- Posterior Urethral Valves: Severe obstruction of urine outflow can lead to massively distended bladder (megacystis), hydronephrosis, and potentially ascites due to urinary extravasation, contributing to hydrops.

Tumors

- Sacrococcygeal Teratoma (SCT): A common fetal tumor, especially when large and highly vascular, can act as a high-output shunt, leading to fetal heart failure and hydrops.

- Neuroblastoma, Hemangioma: Other rare tumors can also cause hydrops by similar mechanisms.

Metabolic Disorders

Various rare genetic metabolic disorders, such as lysosomal storage diseases (e.g., Gaucher disease, Niemann-Pick disease, mucopolysaccharidoses), can lead to organomegaly, impaired organ function, and generalized fluid accumulation.

Lymphatic Abnormalities

- Congenital Lymphangiectasia: Generalized lymphatic malformations leading to widespread fluid accumulation.

- Noonan Syndrome: A genetic disorder often associated with cystic hygromas and lymphatic dysplasia.

Maternal Conditions (indirectly cause fetal hydrops)

- Maternal Diabetes: Poorly controlled diabetes can sometimes lead to fetal macrosomia and cardiomegaly, contributing to hydrops.

- Mirror Syndrome (Ballantyne Syndrome): A rare but severe complication where the mother develops edema, hypertension, and proteinuria, mirroring the hydropic state of the fetus. This is a severe maternal complication of fetal hydrops, not a direct cause, but signifies severe fetal disease.

Idiopathic Hydrops Fetalis

Despite extensive investigation, a cause remains unidentified in a decreasing percentage of cases (e.g., 10-20%). This category is shrinking with advancements in genetic testing and imaging.

Clinical Presentation of Hydrops Fetalis

The clinical presentation of hydrops fetalis varies depending on the gestational age at diagnosis and the severity of the fluid accumulation.

Antenatal Presentation (Before Birth)

In most cases, the pregnant person does not experience specific symptoms directly indicative of hydrops fetalis. The condition is most commonly discovered during routine prenatal ultrasound examinations.

Maternal Symptoms (less common)

- Decreased Fetal Movement: If the hydrops is severe enough to compromise fetal well-being.

- Excessive Uterine Size for Gestational Age: Due to polyhydramnios (excess amniotic fluid), which often accompanies hydrops. This can lead to maternal shortness of breath (dyspnea) or premature contractions.

- Mirror Syndrome (Ballantyne Syndrome): A rare but severe complication where the mother develops edema, hypertension, and proteinuria, mirroring the hydropic state of the fetus. This is a critical sign of severe fetal compromise.

Ultrasound Findings (Primary Diagnostic Tool)

Hydrops fetalis is formally diagnosed on ultrasound when there is abnormal fluid accumulation in at least two of the following fetal compartments:

- Skin Edema (Anasarca): Generalized skin thickening, often defined as skin thickness greater than 5 mm. This is a hallmark sign.

- Pleural Effusion: Fluid surrounding the lungs, appearing as anechoic (black) areas in the fetal chest, potentially causing lung compression and displacing the heart.

- Pericardial Effusion: Fluid around the heart, seen as an anechoic rim surrounding the myocardium. A pericardial effusion greater than 2 mm is generally considered pathological.

- Ascites: Fluid in the abdominal cavity, appearing as anechoic fluid outlining abdominal organs like the liver and intestines.

Associated Ultrasound Findings (not strictly diagnostic criteria, but often present)

- Polyhydramnios: Excessive amniotic fluid.

- Placentomegaly: Abnormally thick and edematous placenta, often with a “ground-glass” appearance.

- Fetal Organomegaly: Enlargement of organs like the liver or spleen (hepatosplenomegaly).

- Abnormal Doppler Flow: Signs of fetal anemia (e.g., increased Middle Cerebral Artery (MCA) peak systolic velocity) or cardiac compromise (e.g., abnormal umbilical artery or venous Doppler).

Postnatal Presentation (After Birth)

Newborns with hydrops fetalis are often critically ill at birth and may present with:

- Severe Generalized Edema: Obvious swelling of the entire body.

- Respiratory Distress: Due to pleural effusions compressing the lungs or pulmonary hypoplasia.

- Pallor or Jaundice: Indicating severe anemia or hemolysis.

- Hepatosplenomegaly

- Cardiovascular Compromise: Signs of heart failure, such as poor perfusion, weak pulses, or arrhythmias.

- Oliguria/Anuria: Poor urine output if renal function is compromised.

- Bleeding tendencies: Due to platelet dysfunction or consumptive coagulopathy in severe cases.

- Dysmorphic Features: If the hydrops is due to a genetic syndrome.

Investigations of Hydrops Fetalis

Once hydrops fetalis is identified on ultrasound, the diagnostic process shifts to determining the underlying cause, which is crucial for guiding management and counseling. This involves a comprehensive, often multidisciplinary approach.

Initial Maternal Evaluation

- Blood Type and Antibody Screen (Indirect Coombs’ Test): Essential to rule out or confirm immune hydrops due to Rh or other red blood cell alloimmunization.

- Infectious Disease Serology (TORCH Screen): Tests for Toxoplasmosis, Other (Parvovirus B19, Syphilis, Varicella, Zika), Rubella, Cytomegalovirus, Herpes Simplex Virus. Parvovirus B19 is a key one to check.

- Hemoglobin Electrophoresis: To screen for alpha-thalassemia carrier status if the mother is at risk.

- Other Maternal Conditions: Depending on history, tests for maternal diabetes, thyroid disorders, etc.

Detailed Fetal Imaging

Beyond confirming hydrops, this aims to identify specific structural anomalies.

- Detailed Anatomic Survey: Looking for cardiac defects, lung masses (e.g., CCAM), diaphragmatic hernia, urinary tract obstructions, or tumors.

- Fetal Echocardiography: A specialized ultrasound to evaluate the fetal heart structure and function in detail, identifying arrhythmias, structural defects, or myocardial dysfunction.

- Doppler Studies:

- Middle Cerebral Artery (MCA) Peak Systolic Velocity (PSV): The most sensitive and specific non-invasive marker for fetal anemia. Increased velocity suggests anemia due to increased blood flow to the brain in an attempt to compensate for low oxygen.

- Umbilical Artery/Vein Doppler: To assess placental resistance and venous return.

Invasive Fetal Diagnostic Procedures (if indicated and feasible)

These procedures provide definitive diagnostic information about the fetus, but carry a small risk.

- Amniocentesis

- Fetal Karyotype and Chromosomal Microarray (CMA): To detect chromosomal abnormalities (e.g., aneuploidies like Trisomies, Turner syndrome) or smaller genetic deletions/duplications.

- Viral PCR: To detect viral DNA/RNA (e.g., Parvovirus B19, CMV) in amniotic fluid.

- Biochemical Assays: Rarely, for suspected metabolic disorders.

- Cordocentesis (Fetal Blood Sampling): Directly obtains fetal blood and is crucial for:

- Fetal Complete Blood Count (CBC) and Reticulocyte Count: To confirm and quantify fetal anemia.

- Fetal Blood Type and Direct Antiglobulin Test (DAT): Essential for immune hydrops, confirming hemolysis in the fetus.

- Serum Protein/Albumin: To assess oncotic pressure.

- Viral PCR from Fetal Blood: More definitive for some infections than amniotic fluid.

- Fetal Karyotype/CMA: If amniocentesis was not performed or results are inconclusive.

- Enzyme Assays: For specific metabolic disorders.

Postnatal Investigations (if born alive)

- Thorough physical examination, CBC, blood type, DAT, bilirubin, liver and renal function tests.

- Chest X-ray, echocardiogram, and other imaging as indicated.

- Genetic testing (karyotype, CMA, specific gene panels/exome sequencing) as per antenatal findings or if the cause remains elusive.

- Specific infectious disease workup.

- Metabolic screening.

- Autopsy: Recommended in cases of fetal demise or neonatal death where the cause remains undetermined, to provide a definitive diagnosis for parental counseling.

Management and Treatment of Hydrops Fetalis

The treatment and management of hydrops fetalis are complex and highly dependent on identifying the underlying cause, the severity of the fluid accumulation, and the gestational age at diagnosis. A multidisciplinary team, including maternal-fetal medicine specialists, neonatologists, pediatric cardiologists, geneticists, and other subspecialists, is essential for optimal care.

Antenatal Management (During Pregnancy)

The primary goals of antenatal management are to treat the underlying cause if possible, stabilize the fetal condition, and allow the pregnancy to continue to a gestational age where postnatal survival is more likely.

General Antenatal Management Considerations

- Close Monitoring: Regular ultrasound scans, fetal echocardiograms, and Doppler studies to assess the resolution or progression of hydrops and fetal well-being.

- Maternal Monitoring: Monitoring for mirror syndrome, which necessitates immediate delivery.

- Counselling: Comprehensive and empathetic counseling of parents about the prognosis, treatment options, and potential long-term outcomes, which can be highly variable.

- Referral to Tertiary Center: Management of hydrops fetalis is best done in a tertiary care center with expertise in fetal medicine and a Level III/IV Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU).

Perinatal Management (Around Birth)

The delivery plan is meticulously coordinated between the obstetric and neonatal teams, often in a tertiary center.

- Timing and Mode of Delivery: This depends on the fetal condition, gestational age, and the underlying cause. Early delivery may be considered if antenatal interventions fail, the fetus is decompensating, or if there’s significant maternal compromise (e.g., mirror syndrome). Cesarean section is often chosen, especially if there are large effusions that could obstruct vaginal delivery or if immediate neonatal resuscitation is anticipated.

- Preparation for Delivery: A full resuscitation team (neonatologists, respiratory therapists) must be present. Equipment for airway management (intubation, mechanical ventilation), fluid drainage, and vascular access should be readily available.

Postnatal Management (After Birth)

Newborns with hydrops fetalis are often critically ill and require immediate intensive care.

Immediate Resuscitation and Stabilization

- Airway and Breathing Support: Many infants require immediate intubation and mechanical ventilation due to respiratory distress from pleural effusions or pulmonary hypoplasia.

- Fluid Management: Aggressive drainage of effusions (thoracentesis, paracentesis) may be necessary to improve lung function and relieve pressure on the heart. Diuretics might be used to help remove excess fluid.

- Circulatory Support: Management of shock and heart failure, which may involve volume expanders, inotropes (medications to strengthen heart contractions), and blood transfusions if anemic.

- Temperature Regulation: Hydropic infants are prone to hypothermia due to their large surface area and compromised circulation.

- Correction of Metabolic Imbalances: Addressing hypoglycemia, electrolyte abnormalities, and acidosis.

Diagnosis Confirmation and Cause-Specific Treatment

Postnatal investigations (blood tests, echocardiogram, genetic testing, infectious disease workup) are often performed to confirm the antenatal diagnosis or identify the cause if it was unknown. Treatment of the underlying cause is continued if diagnosis is confirmed.

Prognosis and Long-Term Follow-up

The prognosis for hydrops fetalis is highly variable and depends significantly on the underlying cause, the gestational age at diagnosis, and the severity of the hydrops.

- Mortality: Overall, hydrops fetalis carries a high mortality rate, especially when diagnosed early in gestation or if the underlying cause is untreatable or severe (e.g., certain chromosomal anomalies, severe alpha-thalassemia major without successful intervention).

- Morbidity: Survivors often face significant long-term morbidity related to their underlying condition or complications from the hydrops itself, including:

- Neurological Impairment: Due to prematurity, hypoxia, or direct brain involvement from certain causes.

- Chronic Lung Disease: Especially if prolonged ventilation or significant pleural effusions were present.

- Cardiac Dysfunction: Persistent heart failure or arrhythmias.

- Developmental Delays: Requiring early intervention programs.

- Hearing Loss: Particularly with congenital CMV infection.

- Renal or Liver Dysfunction: Depending on the initial insult.

Long-term follow-up by a multidisciplinary pediatric team is crucial to address these potential morbidities and optimize the child’s development and quality of life. The significant advances in fetal diagnosis and intervention have steadily improved outcomes for some forms of hydrops fetalis.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the difference between erythroblastosis fetalis and hydrops fetalis?

While the terms “erythroblastosis fetalis” and “hydrops fetalis” are sometimes used interchangeably in historical contexts, especially when discussing Rh disease, it’s crucial to understand their distinct meanings in modern medical terminology.

- Erythroblastosis Fetalis is a specific disease process that refers to a severe hemolytic anemia in the fetus or newborn, characterized by the presence of large numbers of immature red blood cells (erythroblasts) in the fetal blood. This condition is primarily caused by immune-mediated destruction of fetal red blood cells, most commonly due to Rh alloimmunization (Rh incompatibility between mother and fetus). In essence, the mother’s antibodies attack and destroy the baby’s red blood cells.

- Hydrops Fetalis is a symptom or a clinical manifestation characterized by the excessive accumulation of fluid in at least two different fetal body compartments (e.g., skin edema, pleural effusion, pericardial effusion, ascites). It is the end-stage consequence of various underlying conditions that severely disrupt fetal fluid balance.

The relationship between the two is that erythroblastosis fetalis (severe immune-mediated hemolytic anemia) is a cause of hydrops fetalis.

Why does parvovirus cause fetal hydrops?

Parvovirus B19 causes fetal hydrops primarily through two main mechanisms. Firstly, the virus has a unique tropism for erythroid progenitor cells (immature red blood cell precursors) in the fetal bone marrow and liver. By infecting and destroying these cells,

Parvovirus B19 leads to a severe suppression of red blood cell production, resulting in profound fetal anemia. This severe anemia forces the fetal heart to work much harder to deliver oxygen to tissues, ultimately leading to high-output cardiac failure.

Secondly, the virus can also directly infect myocardial cells, causing myocarditis (inflammation of the heart muscle), which further impairs cardiac function and contributes to heart failure.

The combination of severe anemia and myocardial dysfunction culminates in increased hydrostatic pressure and impaired fluid regulation, leading to the widespread fluid accumulation characteristic of hydrops fetalis.

What is the triad of hydrops fetalis?

When discussing the “triad of hydrops fetalis,” it typically refers to the components of Mirror Syndrome (also known as Ballantyne Syndrome). This is a rare, severe complication where the mother’s body mirrors the pathology of the hydropic fetus.

The triad of Mirror Syndrome consists of:

- Fetal Hydrops: The presence of excessive fluid accumulation in at least two fetal body compartments (skin edema, pleural effusion, pericardial effusion, ascites).

- Placentomegaly: An abnormally enlarged and edematous placenta.

- Maternal Edema: Generalized swelling in the mother, often accompanied by features resembling preeclampsia (hypertension and proteinuria), although the underlying pathophysiology is distinct.

What is the mode of delivery for hydrops fetalis?

The mode of delivery for a fetus with hydrops fetalis is a critical decision made by a multidisciplinary team, primarily based on the underlying cause, the fetal condition, gestational age, and the severity of the hydrops.

While there’s a common perception that cesarean section might improve outcomes, current evidence suggests that cesarean section delivery generally does not improve the perinatal outcomes of hydrops fetalis infants, and vaginal delivery can be considered if the fetal and maternal conditions allow.

Cesarean section is typically reserved for standard obstetric indications such as fetal distress, malpresentation (e.g., breech), or if the large abdominal or thoracic effusions of the fetus would significantly impede vaginal delivery. In cases where mirror syndrome (severe maternal complications mirroring fetal hydrops) develops, prompt delivery, often by cesarean section, becomes necessary for maternal safety.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) Clinical Guideline #7: Norton, Mary E. et al.American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Volume 212, Issue 2, 127 – 139.

- Dalton, S. E., Griffith, A. M., Kennedy, A. M., & Woodward, P. J. (2025). Differential Diagnosis of Hydrops Fetalis: An Imaging Guide. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc, 45(3), e240158. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.240158

- Bukowski, R., & Saade, G. R. (2000). Hydrops fetalis. Clinics in perinatology, 27(4), 1007–1031. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0095-5108(05)70061-0

- Maranto, M., Cigna, V., Orlandi, E., Cucinella, G., Lo Verso, C., Duca, V., & Picciotto, F. (2021). Non-immune hydrops fetalis: Two case reports. World journal of clinical cases, 9(22), 6531–6537. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i22.6531

- Apkon M. (1995). Pathophysiology of hydrops fetalis. Seminars in perinatology, 19(6), 437–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0146-0005(05)80051-5

- Khairudin D, Mone F, & Navaratnam K. (2023). Non-immune hydrops fetalis: a practical guide for obstetricians. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist.

- Chui, D. H., & Waye, J. S. (1998). Hydrops fetalis caused by alpha-thalassemia: an emerging health care problem. Blood, 91(7), 2213–2222.

- Younge T, Ottolini KM, Al-Kouatly HB, Berger SI. Hydrops fetalis: Incidence, Etiologies, Management Strategies, and Outcomes. Research and Reports in Neonatology. 2023;13:81-92

https://doi.org/10.2147/RRN.S411736 - Vanaparthy R, Vadakekut ES, Mahdy H. Nonimmune Hydrops Fetalis. [Updated 2024 Aug 11]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563214/