TL;DR

Hematoma is a localized collection of blood outside of blood vessels, distinct from a simple bruise.

- Causes ▾: Can be traumatic (blunt force, penetrating, surgery) or non-traumatic (spontaneous rupture, bleeding disorders, medications).

- Symptoms ▾: Local symptoms include pain, swelling, discoloration. Systemic symptoms may indicate significant blood loss or compression.

- Laboratory Investigations ▾: CBC assesses blood loss and platelets. Coagulation studies evaluate clotting. Others may identify underlying issues.

- Imaging Studies ▾: Crucial for location, size, age, and complications. Ultrasound, CT, MRI, and X-ray provide different information.

- Treatment & Management ▾: Ranges from conservative RICE therapy to drainage or surgical intervention, depending on severity and location.

- Potential Complications ▾: Include infection, re-bleeding, compartment syndrome, nerve damage, and complications specific to the hematoma’s location (e.g., intracranial pressure).

*Click ▾ for more information

Introduction

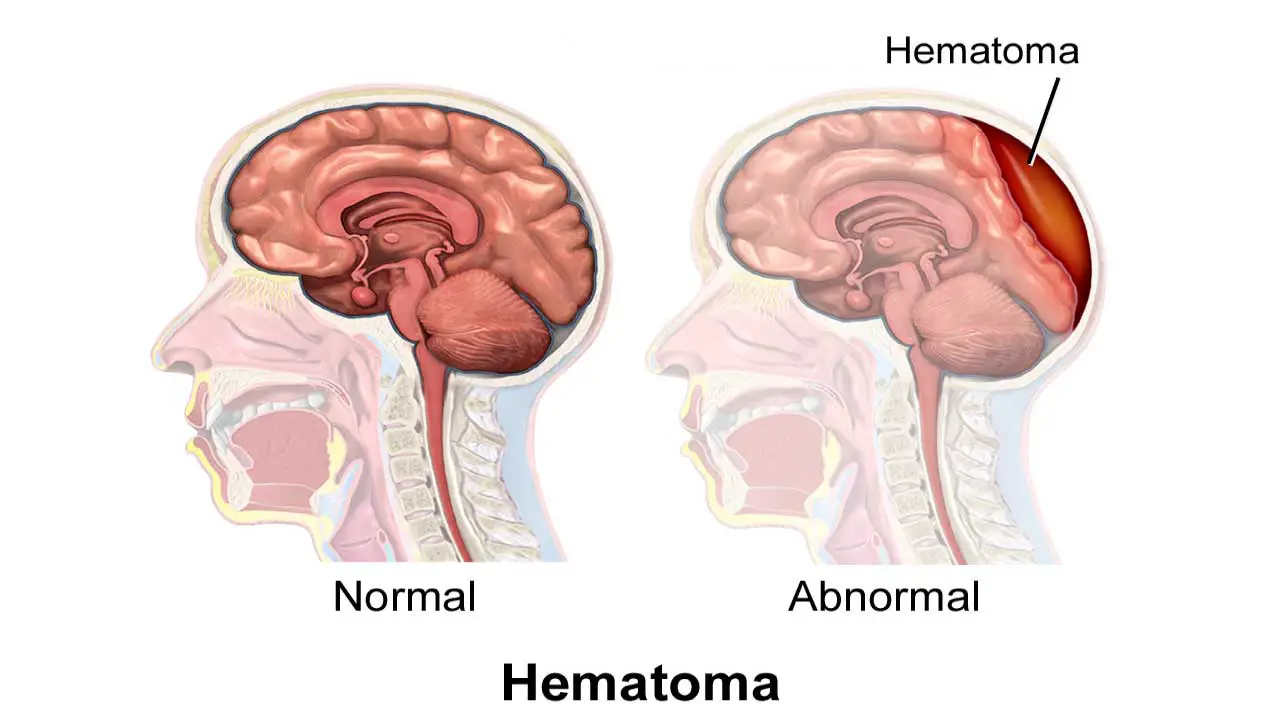

A hematoma is essentially a collection of blood that has leaked out of blood vessels and accumulated in a tissue space, organ, or body cavity. Think of it as a localized “bruise” that can occur both under the skin and deeper within the body.

Hematomas hold significant clinical importance as they frequently serve as indicators of underlying injury, ranging from minor trauma to severe accidents, and can even point towards non-traumatic etiologies such as bleeding disorders, vascular weaknesses, or medication side effects.

Beyond their diagnostic value, the physical presence of a hematoma can lead to a cascade of complications. Their accumulation of blood in confined spaces can exert substantial pressure on adjacent tissues, nerves, and blood vessels, potentially resulting in pain, impaired function, and in severe cases, irreversible damage like neurological deficits or compartment syndrome.

Hematomas are not static entities as they carry risks of infection, recurrent bleeding, and long-term sequelae such as calcification or organization that may necessitate further intervention.

The identification and thorough evaluation of a hematoma, considering its size, location, and evolution, are crucial steps in guiding appropriate management strategies, ranging from conservative measures to more invasive procedures like drainage or surgical evacuation.

Causes of Hematomas

Traumatic Causes

- Blunt Force Trauma: Impacts from falls, collisions, sports injuries, or assaults that damage blood vessels without breaking the skin.

- Penetrating Injuries: Wounds from sharp objects (knives, needles, bullets) that directly lacerate blood vessels.

- Surgical Procedures: Intentional incisions and tissue manipulation during surgery inevitably disrupt blood vessels, leading to localized hematoma formation post-operatively.

- Fractures: Broken bones can damage adjacent blood vessels, resulting in hematomas within the surrounding tissues.

Non-Traumatic Causes

- Spontaneous Rupture of Blood Vessels: Weakened blood vessel walls due to conditions like hypertension, aneurysms, or atherosclerosis can rupture spontaneously, leading to internal bleeding and hematoma formation.

- Underlying Medical Conditions

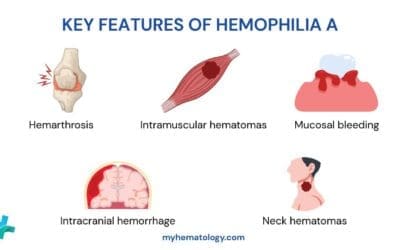

- Bleeding Disorders: Genetic conditions (e.g., hemophilia, von Willebrand disease) or acquired conditions (e.g., disseminated intravascular coagulation – DIC) that impair the body’s clotting ability.

- Thrombocytopenia: Low platelet count, reducing the body’s ability to form initial blood clots.

- Liver Disease: Impaired production of clotting factors by the liver.

- Connective Tissue Disorders: Conditions like Ehlers-Danlos syndrome can cause fragile blood vessels.

- Vitamin Deficiencies: Lack of vitamins like Vitamin K deficiency, essential for clotting factor synthesis.

- Medications

- Anticoagulants: Drugs like warfarin, heparin, and direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) inhibit the clotting process.

- Antiplatelet Drugs: Medications such as aspirin and clopidogrel reduce platelet aggregation.

- Age-Related Vascular Fragility: As individuals age, blood vessels can become more fragile and prone to rupture, even with minor trauma or spontaneously.

- Increased Intravascular Pressure: Conditions that increase pressure within blood vessels (e.g., forceful coughing, vomiting) can occasionally lead to rupture.

Pathophysiology of Hematoma

The formation of a hematoma is a direct consequence of blood vessel damage leading to extravasation – the leakage of blood out of the circulatory system and into the surrounding tissues or body cavities. This process typically unfolds in the following stages.

- Vessel Injury: Trauma, disease processes, or other factors cause a disruption in the integrity of the blood vessel wall, whether it’s a small capillary, a venule, or an arteriole.

- Hemorrhage: Blood under pressure within the damaged vessel escapes into the interstitial space or a potential space (like the subdural or epidural space in the brain). The rate and volume of bleeding depend on the size and type of the injured vessel, as well as the individual’s coagulation status.

- Initial Hemostasis: The body attempts to stop the bleeding through primary hemostasis.

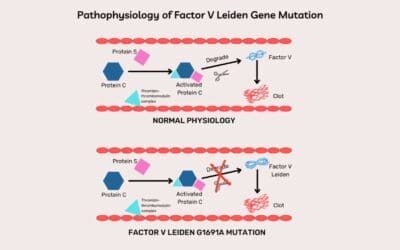

- Secondary Hemostasis (Coagulation Cascade): The coagulation cascade is activated, a complex series of enzymatic reactions that ultimately leads to the formation of fibrin. Fibrin strands reinforce the platelet plug, creating a more stable clot.

- Hematoma Formation: As blood continues to leak and the clotting process proceeds, a localized collection of blood forms outside the blood vessels. This collection occupies space and can exert pressure on surrounding structures.

- Inflammatory Response: The presence of blood in the tissues triggers an inflammatory response. Immune cells migrate to the area, and inflammatory mediators are released. This contributes to the pain, swelling, and warmth often associated with hematomas.

- Clot Retraction and Organization: Over time, the blood clot begins to retract, reducing the size of the hematoma. Enzymes break down the fibrin clot. Fibroblasts migrate into the area and begin to deposit collagen, leading to the organization of the hematoma.

- Resolution: Eventually, the blood components are reabsorbed by the body. Hemoglobin is broken down, leading to the characteristic color changes of a resolving bruise (red/blue -> purple/black -> green/yellow -> brown). The organized tissue may be replaced by normal tissue or result in a small scar.

The specific characteristics and clinical significance of a hematoma are heavily influenced by its location, size, the rate of bleeding, and the surrounding anatomical structures. For instance, a small subcutaneous hematoma will have a different clinical course and implications than a rapidly expanding epidural hematoma in the brain.

Signs and Symptoms of Hematoma

The symptoms of a hematoma can vary significantly depending on its location, size, and the structures it affects. Superficial hematomas are often more obvious, while deeper or internal hematomas may present with more subtle or systemic signs. Here’s a more detailed breakdown of potential symptoms:

Local Symptoms (at or near the site of the hematoma)

- Pain and Tenderness: This is a common initial symptom due to the stretching and irritation of nerve endings by the accumulating blood and the subsequent inflammatory response. The intensity of pain can range from mild discomfort to severe throbbing. Palpation of the area will often elicit tenderness.

- Swelling: The collection of blood creates a localized swelling or a palpable mass. The size and firmness of the swelling will depend on the amount of blood that has extravasated. Superficial hematomas may feel spongy or firm.

- Discoloration of the Skin: This is a hallmark sign of superficial hematomas and occurs as blood breaks down in the tissues. The extent and intensity of discoloration depend on the size and depth of the hematoma. Deeper hematomas may have minimal or no visible skin discoloration initially. The color changes typically follow a predictable pattern:

- Initially: Red or bluish-black due to the presence of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood.

- Over several days: Darkens to a purplish or black hue as the hemoglobin degrades.

- After a week or more: Gradually fades to greenish-yellow and then brownish as bilirubin and hemosiderin (byproducts of hemoglobin breakdown) are absorbed.

- Increased Warmth: The inflammatory response associated with the hematoma can cause the area to feel warmer than the surrounding tissue.

- Loss of Function or Restricted Movement: If the hematoma is located near a joint or involves muscles, the swelling and pain can limit the range of motion and cause difficulty using the affected limb or body part. For example, an intramuscular hematoma in the thigh can make walking painful and restricted.

- Paresthesia (Numbness or Tingling): If the hematoma compresses or irritates nearby nerves, it can lead to sensations of numbness, tingling, or “pins and needles” in the affected area or along the nerve’s distribution.

Systemic Symptoms (less common, but indicative of a more significant issue)

- Signs of Significant Blood Loss: Large internal hematomas can lead to a significant loss of blood volume, resulting in systemic symptoms. In severe cases, this can progress to shock.

- Dizziness or Lightheadedness: Due to reduced blood flow to the brain.

- Tachycardia: Increased heart rate as the body tries to compensate for the reduced blood volume.

- Hypotension

- Weakness and Fatigue: General feeling of being unwell due to blood loss.

- Symptoms Related to Compression of Internal Structures: The clinical presentation can be highly variable depending on the location of an internal hematoma.

- Intracranial Hematomas (Epidural, Subdural, Intracerebral): Can cause severe headache, nausea, vomiting, altered level of consciousness (confusion, drowsiness), seizures, weakness or paralysis on one side of the body, speech difficulties, vision changes, and unequal pupil size. These are medical emergencies.

- Spinal Hematomas: Can lead to back pain, weakness or paralysis of the limbs, bowel or bladder dysfunction.

- Abdominal or Pelvic Hematomas: May present with abdominal pain, distension, tenderness, and potentially signs of internal bleeding.

- Hematomas in Limbs (Compartment Syndrome): Severe pain out of proportion to the injury, pain with passive stretching of the muscles, paresthesia, pallor, pulselessness (late sign), and paralysis (late sign). This is also a medical emergency.

Symptoms Related to Specific Locations

- Subungual Hematoma (under the fingernail or toenail): Throbbing pain, pressure under the nail, and a dark discoloration of the nail bed.

- Cephalohematoma (in newborns, between the skull and periosteum): A localized swelling on the baby’s head that doesn’t cross suture lines.

- Aural Hematoma (in the ear, often in animals but can occur in humans): Swelling and deformity of the ear pinna.

Laboratory Investigations

Laboratory investigations in hematoma primarily aim to:

- Assess the extent of blood loss.

- Evaluate the patient’s coagulation status to identify underlying bleeding disorders or medication effects.

- Rule out other conditions that might mimic or contribute to hematoma formation.

The findings are often normal in simple traumatic hematomas, and abnormalities may point towards the underlying cause or systemic complications.

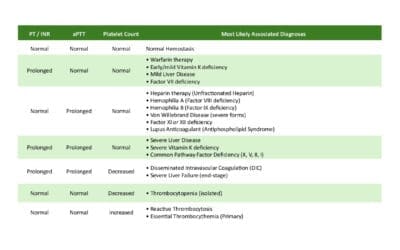

| Laboratory Investigation | Potential Findings Suggesting Underlying Issues |

| Complete Blood Count (CBC) | Low hemoglobin and hematocrit indicating anemia due to blood loss. Low platelet count (thrombocytopenia) suggesting a potential cause of bleeding or a complication like DIC. |

| Coagulation Studies (PT/INR) | Prolonged PT/INR suggesting liver disease (impaired clotting factor synthesis) or the effect of warfarin. |

| Coagulation Studies (aPTT) | Prolonged aPTT suggesting heparin use or a factor deficiency (e.g., hemophilia). |

| Bleeding Time/Platelet Function Assays | Prolonged bleeding time or abnormal platelet function suggesting a platelet disorder (e.g., von Willebrand disease, medication effect). |

| D-dimer | Significantly elevated levels may also indicate other conditions like deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE). |

| Liver Function Tests (LFTs) | Abnormal LFTs suggesting liver disease as a potential contributing factor to impaired coagulation. |

| Renal Function Tests (RFTs) | Abnormal RFTs may indicate kidney injury (if significant blood loss occurred) or an underlying renal condition. |

| Genetic Testing | Identification of specific genetic mutations in patients with suspected inherited bleeding disorders (e.g., hemophilia, von Willebrand disease) in cases of recurrent or unexplained hematomas. |

Imaging Studies

- Ultrasound: Acute hematomas typically appear as complex fluid collections with varying echogenicity (brightness) depending on the stage of clot formation and liquefaction. Over time, they may become more hypoechoic (darker) as the clot liquefies. Ultrasound is excellent for superficial hematomas and can guide aspiration. Doppler ultrasound can assess blood flow in surrounding vessels.

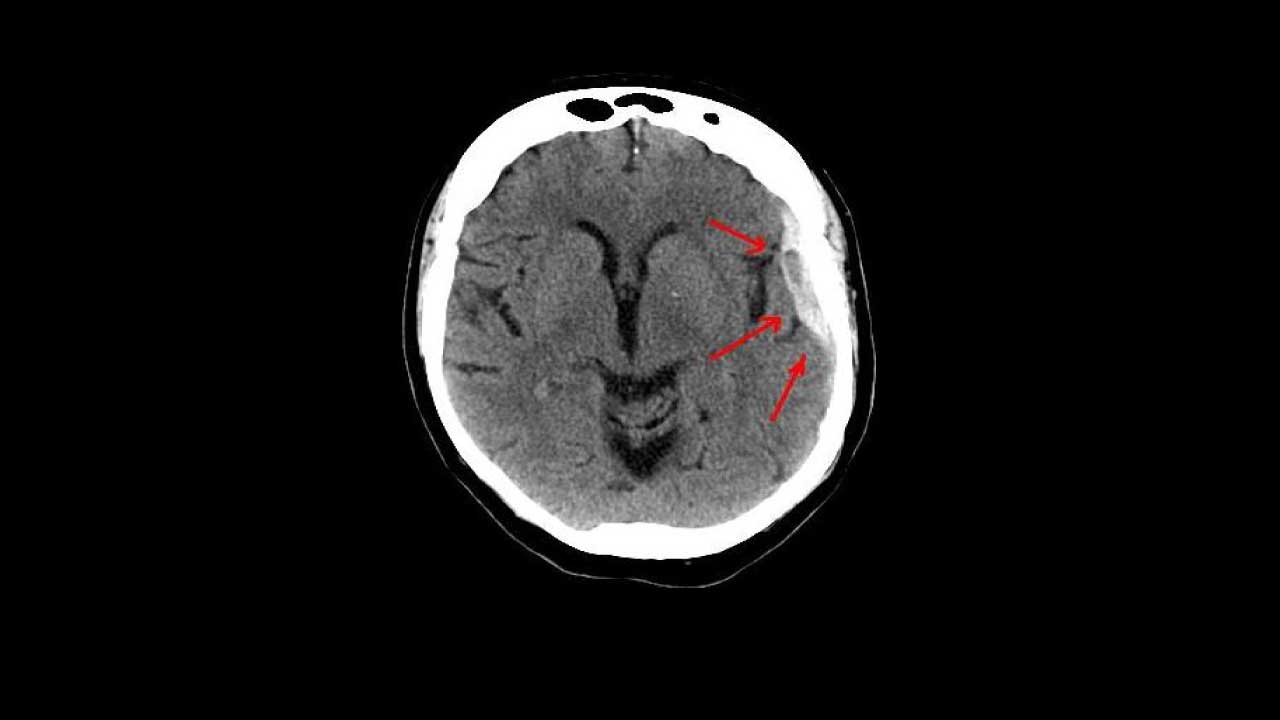

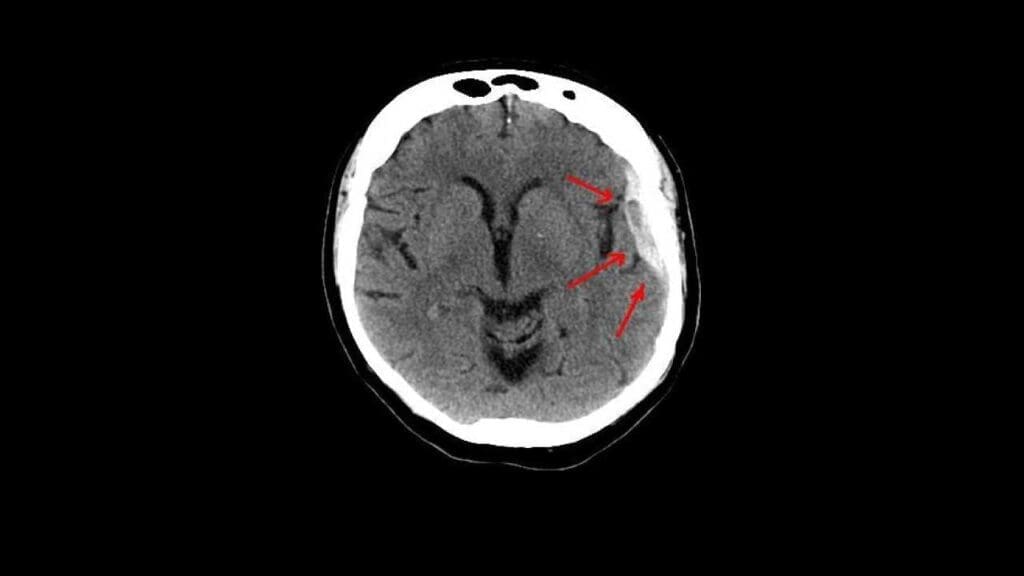

- Computed Tomography (CT Scan): Acute blood is typically hyperdense (bright) on non-contrast CT scans. As the hematoma ages, its density decreases, becoming isodense (similar to brain tissue) and then hypodense (darker) over weeks to months. CT is the primary modality for evaluating intracranial hematomas and internal hematomas in the chest, abdomen, and pelvis due to its speed and ability to detect acute hemorrhage. It can also readily show associated fractures.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): MRI is highly sensitive to changes in blood products and can provide detailed information about the age of a hematoma based on its signal intensity on different sequences (e.g., T1-weighted, T2-weighted, FLAIR). Acute hematomas typically have complex and variable signal intensity. Subacute hematomas often appear bright on both T1 and T2-weighted images due to the presence of methemoglobin. Chronic hematomas may appear dark on T1 and bright on T2. MRI is particularly useful for evaluating hematomas in the brain and spinal cord, as well as soft tissue hematomas in complex anatomical locations. It can also better differentiate hematomas from other lesions.

- X-ray: X-rays are generally not directly useful for visualizing hematomas as they primarily show bony structures. However, they are crucial for identifying associated fractures that may be the cause of the hematoma. In some chronic cases, calcification within a hematoma might be visible on an X-ray.

Treatment and Management

The treatment and management of hematomas are highly dependent on several factors, including the size, location, cause, symptoms, and presence of complications. The primary goals of management are to alleviate pain, reduce swelling, prevent further bleeding, promote healing, and address any underlying conditions or complications.

Conservative Management (Often sufficient for small, uncomplicated hematomas)

RICE Principle

This is the cornerstone of initial management for many superficial and smaller intramuscular hematomas.

- Rest: Immobilizing the affected area helps to prevent further injury and bleeding. This might involve using a sling for an arm hematoma or avoiding weight-bearing for a leg hematoma.

- Ice: Applying ice packs wrapped in a cloth for 15-20 minutes at a time, several times a day, helps to constrict blood vessels, reduce swelling, and alleviate pain. Avoid direct contact of ice with the skin.

- Compression: Applying a gentle but firm elastic bandage around the affected area can help to reduce swelling and support the tissues. Ensure the bandage is not too tight, which could impede circulation.

- Elevation: Raising the injured body part above the level of the heart helps to promote drainage of fluid and reduce swelling.

Pain Management

- Over-the-counter analgesics: Medications like paracetamol (acetaminophen) are often effective for mild to moderate pain. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen or naproxen can also help with pain and inflammation, but should be used cautiously, especially in the immediate post-injury phase, as they may theoretically increase bleeding risk in some individuals (though this is often outweighed by their anti-inflammatory effects). Consult a healthcare professional for appropriate use.

- Stronger analgesics: In cases of severe pain, prescription opioid pain relievers might be necessary, but these are typically used short-term due to the risk of dependence and other side effects.

Observation

Small, stable hematomas often resolve spontaneously over days to weeks as the body reabsorbs the blood. Regular monitoring for any signs of enlargement, increased pain, or complications is important.

Drainage or Aspiration

- Drainage may be considered for

- Large hematomas causing significant pressure, pain, or limitation of movement.

- Hematomas located near nerves or blood vessels where compression could lead to damage.

- Superficial hematomas that are dense and not resolving on their own.

- Suspected infection within the hematoma (though this often requires surgical drainage).

- Techniques

- Needle Aspiration: For more superficial, liquefied hematomas, a needle and syringe can be used to aspirate the fluid. This procedure is often guided by ultrasound to ensure accurate needle placement.

- Incision and Drainage: For larger, more complex, or loculated hematomas (containing multiple compartments), a small incision may be made to allow for drainage of the blood. A drain (a small tube) may be left in place for a few days to facilitate continued drainage. This procedure is typically performed under local anesthesia.

Surgical Intervention

Surgical evacuation of a hematoma may be necessary in the following situations:

- Intracranial Hematomas: Especially epidural and subdural hematomas causing significant mass effect, neurological deterioration, or herniation. These are neurosurgical emergencies. Intracerebral hematomas may also require surgery depending on their size, location, and the patient’s neurological status.

- Compartment Syndrome: Hematomas within a confined fascial compartment in a limb can lead to increased pressure, compromising blood flow to muscles and nerves. This requires urgent surgical decompression (fasciotomy).

- Large or Expanding Hematomas: Hematomas that continue to grow despite conservative measures may require surgical removal to prevent further complications.

- Hematomas Causing Significant Functional Impairment: If a hematoma is severely limiting movement or causing persistent disability and is unlikely to resolve adequately with conservative treatment.

- Chronic Encapsulated Hematomas: Some hematomas can become encapsulated by a fibrous membrane and may require surgical excision if they cause persistent symptoms or cosmetic issues.

- Hematomas Associated with Fractures Requiring Open Reduction and Internal Fixation (ORIF): The hematoma may be addressed during the surgical repair of the fracture.

Management of Underlying Conditions

It is crucial to identify and manage any underlying medical conditions that may have contributed to the hematoma formation.

- Treating bleeding disorders with appropriate medications (e.g., clotting factor concentrates for hemophilia).

- Managing liver disease.

- Controlling hypertension.

- Addressing vitamin deficiencies.

- Medication management: Reviewing and potentially adjusting or discontinuing medications that increase the risk of bleeding, such as anticoagulants and antiplatelet drugs, under the guidance of a healthcare professional. Reversal agents may be necessary in certain situations (e.g., protamine for heparin overdose, vitamin K for warfarin reversal, specific antidotes for DOACs).

Rehabilitation

After the acute phase and as pain and swelling subside, rehabilitation, often involving physical therapy, may be necessary to:

- Restore range of motion and flexibility.

- Strengthen weakened muscles.

- Improve balance and coordination.

- Prevent long-term stiffness or functional limitations, especially if the hematoma involved muscles or joints.

Key Considerations in Management

- Location of the Hematoma: This is the most critical factor influencing treatment. Intracranial, spinal, and those causing compartment syndrome require urgent and often surgical intervention.

- Size and Rate of Expansion: Larger and rapidly expanding hematomas are more concerning and may necessitate more aggressive treatment.

- Symptoms: The severity of pain, functional impairment, and any neurological symptoms guide management decisions.

- Underlying Medical Conditions: Pre-existing bleeding disorders or other medical issues significantly impact the approach to treatment.

- Patient’s Overall Health: The patient’s age, comorbidities, and general health status are important considerations.

The management of a hematoma is a dynamic process that requires careful assessment, ongoing monitoring, and a tailored approach based on the individual patient and the specific characteristics of their hematoma.

Potential Complications

Hematomas often resolve without significant issues. However, it can lead to a range of potential complications depending on their size, location, and the surrounding tissues.

Local Complications (at or near the site of the hematoma)

- Re-bleeding: Especially if the underlying cause of the initial bleeding is not addressed, if there is recurrent trauma, or if the patient is on anticoagulants or has a bleeding disorder, the hematoma can re-accumulate blood, potentially increasing its size and exacerbating symptoms.

- Infection: Hematomas, being collections of blood, can become a breeding ground for bacteria, especially if there was an open wound associated with the initial injury or if drainage procedures are performed. An infected hematoma (abscess) will present with increased pain, redness, warmth, swelling, and potentially fever and pus formation.

- Compartment Syndrome: This is a serious condition that can occur when a hematoma develops within a confined fascial compartment (most commonly in the limbs). The increased pressure from the hematoma can compress nerves and blood vessels, leading to severe pain, paresthesia, muscle ischemia (lack of blood flow), and potentially permanent nerve and muscle damage if not treated urgently with surgical decompression (fasciotomy).

- Nerve Compression and Damage: Hematomas located near nerves can exert pressure, leading to temporary or permanent nerve damage. This can manifest as pain, numbness, tingling, weakness, or paralysis in the area supplied by the affected nerve. The severity depends on the degree and duration of compression.

- Chronic Pain: Even after the hematoma resolves, some individuals may experience chronic pain in the affected area due to nerve irritation, scar tissue formation, or persistent inflammation.

- Calcification or Organization: Over time, a hematoma can become organized by fibrous tissue and may even calcify (deposit calcium). This can result in a firm, sometimes palpable mass that may cause persistent discomfort or cosmetic issues and might require surgical removal in some cases.

- Cosmetic Deformity: Large superficial hematomas, even after resolution, can sometimes leave behind residual discoloration of the skin or changes in the contour of the affected area.

- Adhesion Formation: Hematomas that occur within or between muscles or other tissues can lead to the formation of adhesions (scar tissue that binds tissues together). This can restrict movement and cause pain.

Systemic Complications (affecting the body as a whole)

- Significant Blood Loss and Hypovolemic Shock: Large internal hematomas (e.g., in the abdomen or retroperitoneum) can lead to a significant loss of blood volume, resulting in hypovolemic shock. This is a life-threatening condition characterized by low blood pressure, rapid heart rate, altered mental status, and organ dysfunction due to inadequate tissue perfusion.

- Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC): In rare cases, particularly with large or complex hematomas or underlying medical conditions, the body’s coagulation system can become dysregulated, leading to both excessive clotting and bleeding.

- Sepsis: If a hematoma becomes infected and the infection is not controlled, it can spread to the bloodstream, leading to sepsis, a severe and potentially life-threatening systemic inflammatory response.

- Thromboembolic Events (Rare): While less common, the presence of a large hematoma and associated inflammation could theoretically increase the risk of blood clot formation in nearby veins (deep vein thrombosis – DVT), which could then travel to the lungs (pulmonary embolism – PE).

Location-Specific Complications

- Intracranial Hematomas (Epidural, Subdural, Intracerebral): These are particularly dangerous due to the limited space within the skull. Complications can include increased intracranial pressure (ICP), brain herniation (shifting of brain tissue), neurological deficits (weakness, paralysis, speech problems, vision changes), seizures, coma, and death.

- Spinal Hematomas (Epidural, Subdural, Intramedullary): Can lead to spinal cord compression, resulting in back pain, weakness or paralysis of the limbs, sensory changes, and bowel or bladder dysfunction, potentially leading to permanent neurological impairment.

- Pericardial Hematoma: Blood accumulation in the sac surrounding the heart can lead to cardiac tamponade, a condition where the pressure prevents the heart from filling properly, leading to circulatory failure.

- Retroperitoneal Hematoma: Bleeding into the space behind the abdominal cavity can be difficult to detect and can lead to significant blood loss, pain, and compression of retroperitoneal structures.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How long does a hematoma take to heal?

The healing time for a hematoma can vary significantly depending on several factors, including:

- Size of the hematoma: Smaller hematomas typically resolve faster than larger ones.

- Location of the hematoma: Superficial hematomas under the skin often heal more quickly than deeper intramuscular or internal hematomas. Hematomas in areas with good blood supply may also heal faster.

- Severity of the injury: Hematomas resulting from more significant trauma may take longer to heal.

- Individual factors: Age, overall health, underlying medical conditions (like bleeding disorders or diabetes), and medication use (especially blood thinners) can affect healing time.

- Treatment: Proper home care using the RICE method (Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation) can aid healing. Large or symptomatic hematomas that require drainage or surgical intervention may have a different recovery timeline.

General Timeline

- Minor bruises (small, superficial hematomas): May disappear within 1 to 2 weeks. The color will change over this time as the body breaks down and reabsorbs the blood.

- Larger subcutaneous or intramuscular hematomas: Can take several weeks to a few months to fully resolve. The swelling and pain may subside earlier, but the discoloration can persist for longer.

- Deep or internal hematomas: Healing time is highly variable and depends on the specific location and size. They may take weeks to months, and in some cases, recovery from associated complications can take even longer. For example, intracranial hematomas can have a prolonged recovery period that may extend for many months or even years.

When does a hematoma need to be drained?

A hematoma may need to be drained when it causes significant symptoms or poses a risk of complications. Here are some key situations where drainage might be necessary:

Size and Location

- Large Hematomas: Hematomas that are large and continue to expand can exert pressure on surrounding tissues, nerves, and blood vessels, leading to pain, impaired function, and potential damage.

- Intracranial Hematomas: Hematomas within the skull (epidural, subdural, intracerebral) that cause a mass effect, leading to neurological deficits (headache, confusion, weakness, vision changes), increased intracranial pressure, or brain herniation, require urgent surgical evacuation to prevent permanent brain damage or death.

- Spinal Hematomas: Hematomas compressing the spinal cord can cause back pain, weakness or paralysis of the limbs, and bowel or bladder dysfunction, often necessitating surgical drainage to relieve pressure.

- Compartment Syndrome: Hematomas within a confined muscle compartment (usually in the limbs) that lead to increased pressure, causing severe pain, numbness, and potential muscle and nerve damage, require urgent surgical decompression (fasciotomy).

Symptomatic Relief

- Persistent Pain and Discomfort: If a hematoma causes significant pain that is not relieved by conservative measures (RICE, pain medication), drainage may be considered to alleviate the pressure and discomfort.

- Impaired Functionality: Hematomas that restrict movement or cause significant functional impairment, especially near joints or within muscles, may benefit from drainage to restore mobility.

Risk of Infection

- Hematomas can become infected, especially if there was an associated open wound or if signs of infection develop (increased pain, redness, warmth, swelling, fever, pus). Drainage is often necessary to remove the infected fluid and allow for proper healing.

Failure to Resolve

- Hematomas that do not show signs of resolving or are enlarging over time despite conservative management may need to be drained.

Specific Locations

- Subungual Hematomas: Large, painful hematomas under the fingernail or toenail may be drained to relieve pressure and pain, ideally within the first 48 hours.

- Aural Hematomas: Hematomas in the ear (common in animals but can occur in humans) often require drainage to prevent deformity of the ear pinna (“cauliflower ear”).

Methods of Drainage

- Needle Aspiration: For smaller, more superficial, and liquefied hematomas.

- Incision and Drainage: For larger or more complex hematomas, where a small incision is made to allow the blood to drain. A drain may be left in place.

- Surgical Evacuation: For large, deep, or critical hematomas, especially intracranial or those causing compartment syndrome, requiring a more extensive surgical procedure to remove the blood clot.

It is crucial to consult a healthcare professional for the evaluation and management of a hematoma. They can determine if drainage is necessary based on the individual circumstances. Attempting to drain a hematoma at home is not recommended due to the risk of infection and other complications.

What not to do with a hematoma?

When dealing with a hematoma, it’s important to avoid actions that could worsen the condition or impede healing.

- Don’t apply heat, especially in the initial 24-48 hours: Heat can increase blood flow to the area, potentially leading to more bleeding and swelling. Stick to ice packs during this initial phase.

- Don’t massage the hematoma: Massaging can disrupt the healing process and potentially cause more bleeding or inflammation.

- Don’t drain the hematoma yourself: Attempting to drain a hematoma at home can introduce infection and may not effectively remove the blood collection. Drainage should only be performed by a healthcare professional under sterile conditions if deemed necessary.

- Don’t ignore significant pain or increasing size: If the pain is severe or worsening, or if the hematoma continues to grow, seek medical attention as it could indicate a more serious issue or complication.

- Don’t take NSAIDs (like ibuprofen or aspirin) without consulting a doctor: These medications can have blood-thinning effects and might increase bleeding, especially in the early stages of a hematoma. Paracetamol (acetaminophen) is often a safer over-the-counter pain reliever in this situation, but always check with a healthcare professional.

- Don’t put excessive pressure on the area: While compression can be helpful in the initial management to reduce swelling, avoid wrapping the area too tightly, as this can impede circulation.

- Don’t resume strenuous activity too soon: Allow the hematoma and surrounding tissues adequate time to heal before returning to activities that put stress on the affected area. Premature activity can lead to re-bleeding or delayed healing.

- Don’t ignore signs of infection: Redness, increased warmth, increased swelling, and pus drainage are signs of a potential infection and require medical attention.

- Don’t delay seeking medical advice for hematomas associated with head injuries: Head injuries can lead to serious intracranial hematomas, and any concerning symptoms like severe headache, vomiting, confusion, or neurological changes should be evaluated immediately by a medical professional.

- Don’t disregard hematomas if you have a bleeding disorder or are on blood thinners: Individuals with these conditions may be at higher risk for larger or more problematic hematomas and should seek medical advice for any significant bruising or hematoma formation.

When to worry about a hematoma?

Severe Symptoms

- Intense pain that is not relieved by over-the-counter medication.

- Rapid increase in size or significant swelling.

- Signs of infection such as increased redness, warmth, pus, or fever.

- Restricted movement or loss of function in the affected limb or joint.

- Numbness or tingling in the area of the hematoma.

Specific Locations

- Head Injury: Any hematoma associated with a head injury, especially if there is:

- Severe or persistent headache.

- Vomiting.

- Dizziness or balance problems.

- Confusion or altered mental status.

- Vision changes.

- Weakness or paralysis.

- Seizures.

- Loss of consciousness, even if brief.

- Spinal Area: Hematomas near the spine causing back pain, weakness, numbness, or bowel/bladder problems.

- Extremities: Hematomas in the arms or legs that cause severe pain, swelling, paleness, coolness, or loss of pulse (signs of potential compartment syndrome).

- Under a Nail (Subungual Hematoma): Severe, throbbing pain that doesn’t subside, as pressure buildup may require drainage.

- Ear (Aural Hematoma): Significant swelling and deformity of the ear.

Other Concerning Factors

- Known Bleeding Disorder: If you have a condition that makes you bleed or bruise easily.

- Taking Blood Thinners: If you are on anticoagulant or antiplatelet medications.

- Recurrent or Unexplained Hematomas: Frequent bruising or hematomas without a clear injury.

- Hematoma Doesn’t Improve: If the hematoma doesn’t start to improve (decrease in size and pain, color change) within a couple of weeks.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Goldberg S, Hoffman J. Clinical Hematology Made Ridiculously Simple, 1st Edition: An Incredibly Easy Way to Learn for Medical, Nursing, PA Students, and General Practitioners (MedMaster Medical Books). 2021.

- Khairat A, Waseem M. Epidural Hematoma. [Updated 2023 Jul 31]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK518982/

- Shikhman A, Tuma F. Abdominal Hematoma. [Updated 2023 Apr 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519551/