TL;DR

Venous thromboembolism or also known as VTE is a condition where a blood clot (thrombosis) forms in a deep vein, usually in the leg (deep vein thrombosis) or pelvis, and can travel to the lungs, causing a pulmonary embolism. This is a serious condition that can be life-threatening if not treated promptly.

- Virchow’s Triad ▾: endothelial injury, stasis, and hypercoagulability – explains the underlying mechanisms of clot formation, but various other individual risk factors play a role.

- Symptoms ▾: Early symptoms like leg pain, swelling, and warmth can raise suspicions, while shortness of breath and chest pain could signify a life-threatening PE.

- Related disorders ▾: DVT, PE, chronic venous insufficiency & post-thrombotic syndrome.

- Investigation ▾: D-dimer testing and compression ultrasound are essential investigative tools, though specific situations might require CT scans, MRIs, or V/Q scans.

- Treatment ▾: Anticoagulants, the mainstay of treatment, come in various forms like heparin, warfarin, and DOACs, while thrombolysis and mechanical interventions are reserved for specific cases.

- Prevention ▾: Prophylaxis with compression stockings and low-dose anticoagulants is vital for high-risk patients undergoing surgery or facing prolonged immobilization.

*Click ▾ for more information

What is venous thrombosis (VTE)?

When we talk about thrombosis, we usually focus on arteries because their high-pressure flow makes them prone to sudden, dangerous blockages also known as arterial thrombosis. But don’t underestimate the veins! Venous thrombosis (VTE) is when a clot forms in one of these slower-moving vessels, typically in the legs or pelvis.

VTE is often used interchangeably with a broader term, venous thromboembolism. What’s the difference?

- Venous thrombosis is the formation of the clot itself within the vein.

- Venous thromboembolism refers to the potential consequence of a venous clot – when the clot breaks free, becomes and embolus and travels through the bloodstream to another location, usually the lungs.

So, VTE encompasses both the initial clot formation (venous thrombosis) and the potential for that clot to travel (venous thromboembolism). This distinction is crucial for accurately diagnosing and managing the condition.

What is Thrombosis?

Thrombosis is the formation of a blood clot (called a thrombus) inside a blood vessel. Think of it like a traffic jam within your circulatory system, where blood cells get stuck together instead of flowing smoothly. These clots can partially or completely block the vessel, disrupting the delivery of oxygen and nutrients to vital organs.

The thrombus like a tangled web with three main components:

- Platelets: Platelets clump together at the site of injury to form a plug and stop bleeding. But sometimes, they get overzealous and build up even where they’re not needed, leading to a thrombus.

- Fibrin: Fibrin solidifies the platelet plug into a dense mesh that traps red blood cells. Imagine fibrin strands acting as scaffolding for the clot to grow.

- Red blood cells: These oxygen-carrying cells get caught in the fibrin web, adding bulk and further restricting blood flow.

The balance between these elements is crucial. When the clotting process goes haywire, a thrombus forms, posing a serious threat to health. While clotting is essential for healing wounds, uncontrolled clotting can cause major problems.

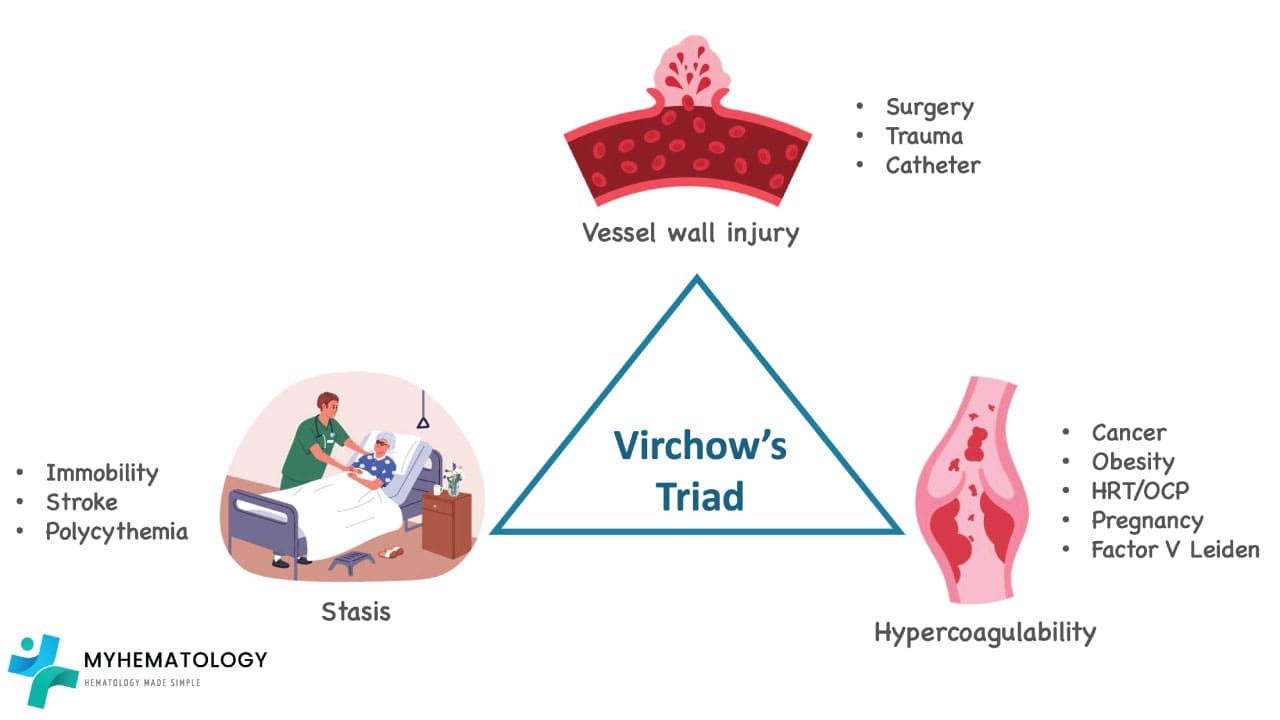

VTE Risk Factors

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) lurks in the shadows, waiting for the perfect storm of risk factors to brew. Understanding these factors, and how they fit into Virchow’s Triad, is key to identifying and preventing this potentially life-threatening condition.

Virchow’s Triad

- Endothelial injury: This is the “trigger” that sets the whole clotting cascade in motion. Think of it as a tear in the vessel lining, inviting platelets and clotting factors to the site of injury. Examples include:

- Inflammation: From infections to autoimmune diseases, inflammation can damage the endothelium.

- Trauma: Surgery, fractures, and even vigorous exercise can cause internal injuries.

- Radiation therapy: This can damage the vascular lining, particularly in the treated area.

- Vascular catheters: These tubes, used for various procedures, can irritate and injure the endothelium.

- Stasis: This is the “slow-down” factor, where sluggish blood flow allows clotting factors to cozy up and form a thrombus. Examples include:

- Prolonged immobilization: Bed rest, casts, and long-distance travel can all lead to stasis.

- Obesity: Excess weight increases pressure in the veins, especially in the legs.

- Pregnancy: Hormonal changes and compression of veins by the growing uterus contribute to stasis.

- Heart failure: This weakens the heart’s pumping capacity, leading to blood pooling in the veins.

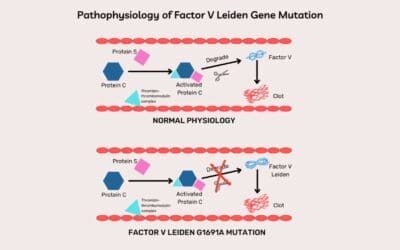

- Hypercoagulability: This is the “overdrive” factor, where the body’s natural clotting system goes into overdrive, producing too many clotting factors or not enough inhibitors. Examples include:

- Inherited thrombophilia: Conditions like Factor V Leiden and Protein C deficiency make individuals prone to clotting.

- Acquired thrombophilia: Certain cancers, infections, and autoimmune diseases can trigger hypercoagulability.

- Hormonal factors: Birth control pills and hormone replacement therapy can increase clotting risk.

- Medications: Some drugs, like corticosteroids and tamoxifen, can promote clotting.

While Virchow’s Triad provides a solid framework, other factors can also play a role:

- Age: The risk of venous thrombosis (VTE) increases with age, particularly after 60 years old.

- Previous VTE: Having had a previous venous thromboembolism (VTE) significantly increases the risk of future events.

- Family history of VTE: Genetic predisposition can also play a role.

- Smoking: This damages the endothelium and increases platelet activity.

- Medical conditions: Certain conditions like inflammatory bowel disease and cancer can increase venous thromboembolism (VTE) risk.

Remember, venous thromboembolism (VTE) is often a multifactorial condition, with several risk factors working together to tip the scales towards clot formation. By understanding these factors, you can better identify at-risk individuals, implement preventative measures, and ultimately save lives.

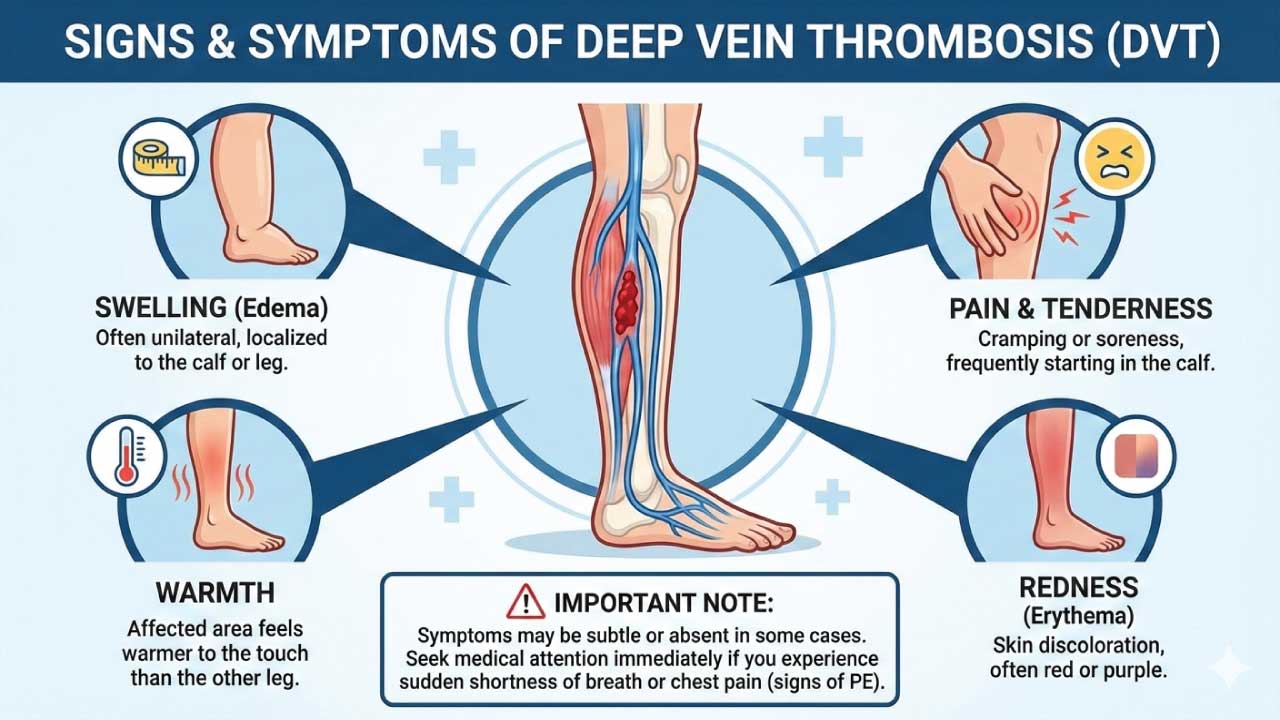

VTE Symptoms and Signs

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) can be a sneaky villain, often lurking in the shadows without throwing up obvious red flags. However, knowing its telltale signs and symptoms can be the key to early diagnosis and preventing potentially life-threatening complications like pulmonary embolism (PE). Let’s delve into the world of VTE symptoms, differentiating between typical and atypical presentations and understanding the significance of each.

Typical Presentation

- Unilateral leg pain: This is the most common clue, with a throbbing or aching sensation often localized to the calf or thigh.

- Swelling: The affected leg appears puffier than the other, sometimes significantly so.

- Tenderness: Pressing on the swollen area elicits pain, like stepping on a hidden bruise.

- Warmth: The affected leg feels warmer to the touch compared to the other leg. Imagine holding a mug of coffee against your skin.

- Skin changes: Discoloration like redness or darkening may appear, especially in later stages. Think of a bruised banana starting to turn brown.

Atypical Presentation

But venous thromboembolism (VTE) isn’t always so obvious. In some cases, it lurks behind the scenes, causing:

- Vague discomfort: Dull ache or tightness in the leg that’s easily mistaken for muscle strain or fatigue.

- Minimal swelling: Noticeable only on close comparison with the other leg.

- Generalized symptoms: Fatigue, fever, and loss of appetite, mimicking various other illnesses.

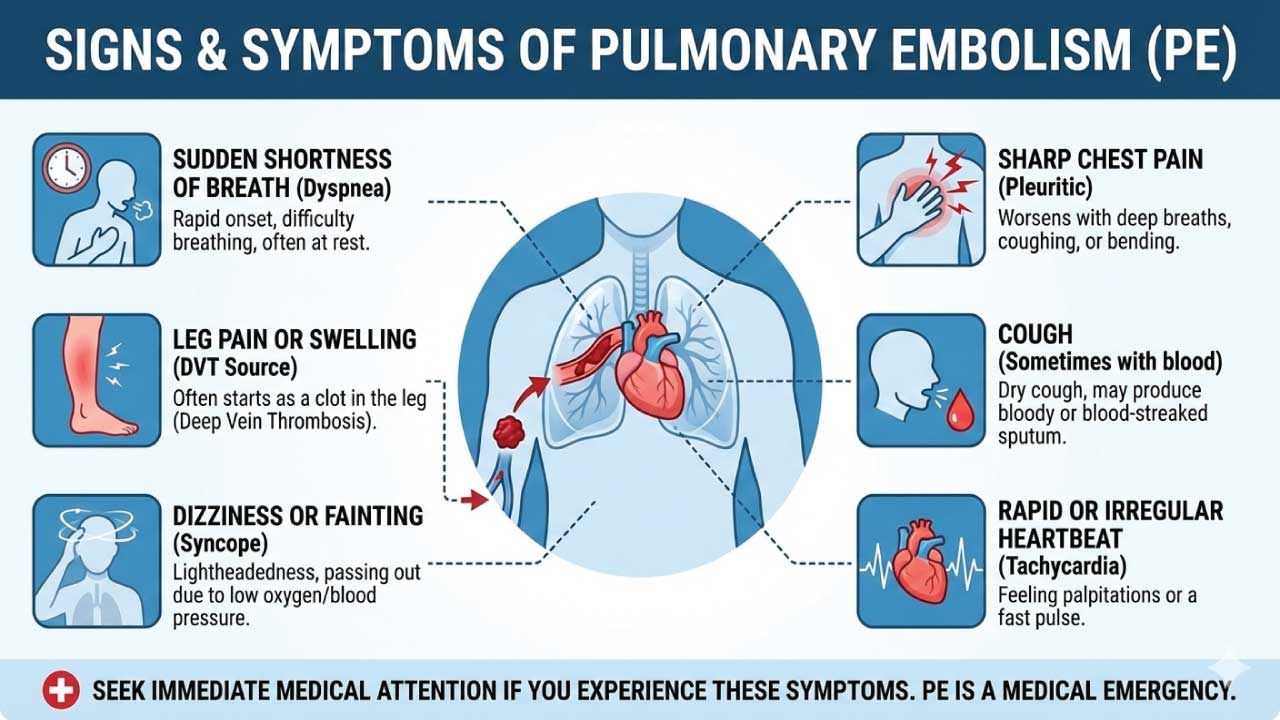

Dyspnea and Chest Pain

Sometimes, venous thromboembolism (VTE) takes a dramatic turn, sending an embolus traveling to the lungs, causing a potentially life-threatening pulmonary embolism (PE). Watch out for these warning signs:

- Sudden dyspnea (shortness of breath): Difficulty catching your breath, even at rest, is a major alarm bell.

- Sharp chest pain: A stabbing or pleuritic pain that worsens with deep breaths or coughing is another worrying sign.

- Coughing up blood: This is a rare but ominous symptom, indicating a severe PE.

Pathophysiology of VTE

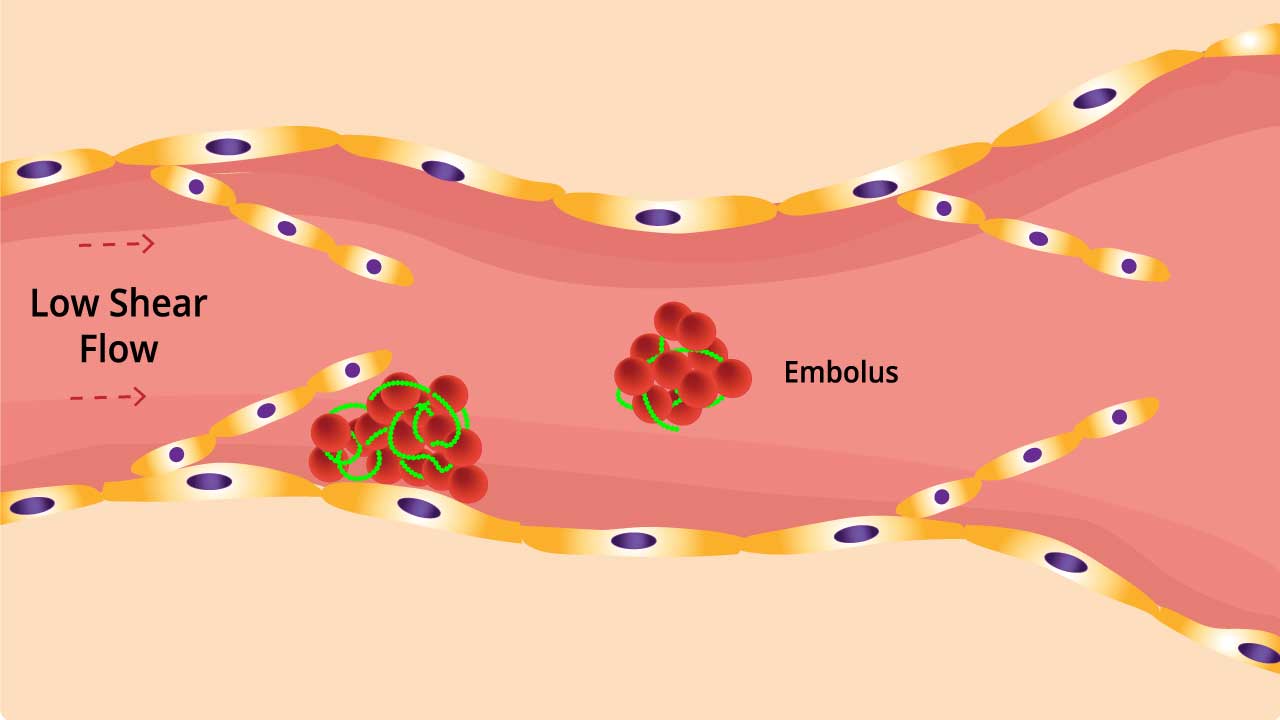

Venous thrombosis tends to occur in areas with decreased or mechanically altered blood flow such as the pockets adjacent to valves in the deep veins of the leg.

While valves help to promote blood flow through the venous circulation, they are also potential locations for venous stasis and hypoxia. Multiple postmortem studies have demonstrated the propensity for venous thrombi to form in the sinuses adjacent to venous valves.

As blood pools, activation products of the coagulation system accumulate locally leading potentially to local hypercoagulability. Activation products of clotting and fibrinolysis can induce endothelial damage which in turn leads to further activation of the hemostasis system. Endothelial damage may also result from distension of the vessel walls by the pooling blood.

Blood flow is further decreased by hyperviscosity due to elevated fibrinogen levels and dehydration. The clot can break off and travel to another part of the body as an embolus. The embolus is dangerous as it can lodge itself in the lungs preventing blood from reaching the lungs and this can be fatal.

Related Disorders of VTE

Venous thrombosis (VTE), the formation of blood clots in veins, isn’t just a standalone condition. It’s a gateway to a cascade of related disorders, each with its own set of complications and potential long-term effects. Let’s delve into some of the most common disorders associated with venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT)

This is the initial formation of a clot in a deep vein, typically in the legs or pelvis. It’s the culprit behind many other venous thromboembolism (VTE)-related issues. Symptoms include leg pain, swelling, warmth, and redness. Left untreated, DVT can lead to:

- Pulmonary embolism (PE): When a DVT breaks free, becomes an embolus and travels to the lungs, it can block a pulmonary artery, causing sudden shortness of breath, chest pain, and even death.

- Post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS): Even after the clot dissolves, damage to the vein can lead to chronic leg pain, swelling, and skin changes.

Pulmonary Embolism (PE)

This is the life-threatening complication of DVT, where an embolus travels to the lungs and blocks an artery. Symptoms include sudden shortness of breath, chest pain, coughing up blood, and rapid heart rate. PE requires immediate medical attention and can be fatal if not treated promptly.

Chronic Venous Insufficiency (CVI)

This condition arises when weakened or damaged veins struggle to pump blood effectively back to the heart. It’s often a consequence of untreated DVT or PTS. Symptoms include chronic leg swelling, fatigue, skin discoloration, and leg ulcers. While not life-threatening, CVI can significantly impact quality of life and requires long-term management.

Post-thrombotic Syndrome (PTS)

This chronic condition develops after a DVT dissolves, leaving behind damaged valves and weakened veins. Symptoms include leg pain, swelling, skin discoloration, and varicose veins. PTS can significantly impact mobility and quality of life, requiring ongoing management and, in some cases, surgical intervention.

Understanding the interconnectedness of these disorders is crucial for:

- Early diagnosis and treatment of venous thromboembolism (VTE): Prompt intervention for DVT can prevent PE and minimize the risk of developing CVI and PTS.

- Effective management of related complications: Each disorder has its own treatment strategies, and understanding the connection helps tailor care to individual needs.

- Preventing future venous thromboembolism (VTE) events: By addressing underlying risk factors and implementing preventive measures, we can break the cycle and reduce the risk of recurrence.

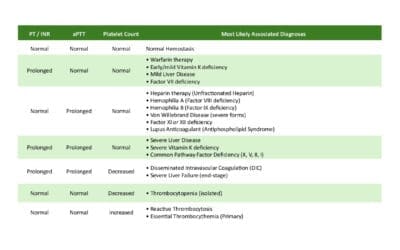

General Laboratory Investigations of VTE

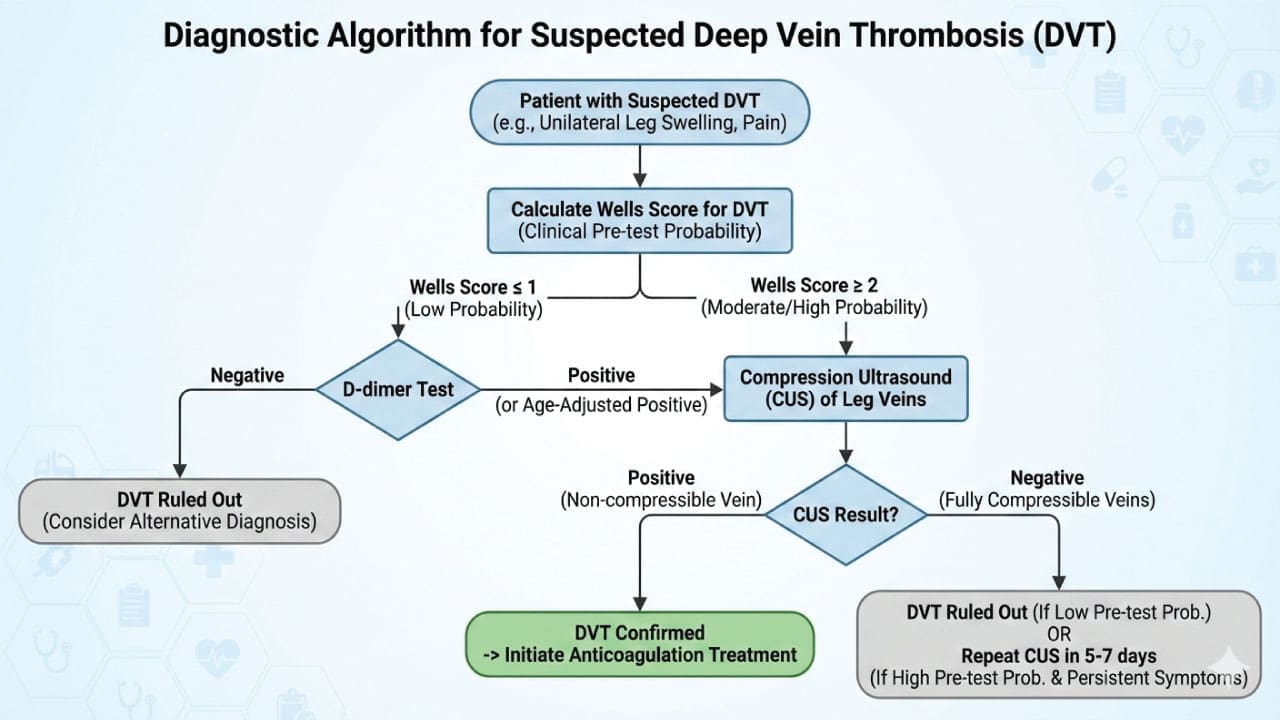

The modern diagnostic approach to Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) relies heavily on validated clinical decision-making algorithms to establish a pre-test probability before any imaging is ordered, thereby preventing unnecessary radiation exposure, contrast-induced nephropathy, and healthcare costs.

The diagnostic pathway typically begins with the Wells Score, a point-based clinical prediction rule that stratifies patients into “likely” or “unlikely” categories for either Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) or Pulmonary Embolism (PE) based on presenting signs, symptoms, and medical history.

Wells Score: Clinical Prediction Rules for VTE

The Wells Score is the most widely used clinical decision-making tool to determine the pre-test probability of Venous Thromboembolism. For your website students, these tables provide a clear breakdown of how points are allocated and interpreted.

Wells Score for Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT)

| Clinical Feature | Points |

|---|---|

| Active cancer (treatment ongoing, within 6 months, or palliative) | +1 |

| Paralysis, paresis, or recent plaster immobilization of the lower extremities | +1 |

| Recently bedridden for ≥ 3 days or major surgery within 12 weeks | +1 |

| Localized tenderness along the distribution of the deep venous system | +1 |

| Entire leg swelling | +1 |

| Calf swelling > 3 cm compared to asymptomatic leg (measured 10cm below tibial tuberosity) | +1 |

| Pitting edema confined to the symptomatic leg | +1 |

| Collateral superficial veins (non-varicose) | +1 |

| Previous documented DVT | +1 |

| Alternative diagnosis is at least as likely as DVT | -2 |

Interpretation:

- 0 or less: Low probability (D-dimer indicated)

- 1 – 2 points: Moderate probability

- 3 or more: High probability (Proceed directly to Ultrasound)

Wells Score for Pulmonary Embolism (PE)

| Clinical Feature | Points |

|---|---|

| Clinical signs and symptoms of DVT (leg swelling, pain on palpation) | +3.0 |

| Heart rate > 100 beats per minute | +1.5 |

| Immobilization (≥ 3 days) or surgery within previous 4 weeks | +1.5 |

| Previous DVT or PE | +1.5 |

| Hemoptysis (coughing up blood) | +1.0 |

| Malignancy (on treatment, treated in last 6 months, or palliative) | +1.0 |

| An alternative diagnosis is less likely than PE | +3.0 |

Interpretation (Three-Tier Model)

- 0 – 1 point: Low probability

- 2 – 6 points: Moderate probability

- 7 or more: High probability

Interpretation (Two-Tier/Simplified Model – Common in ER)

- 0 – 4 points: PE Unlikely (D-dimer indicated)

- > 4 points: PE Likely (Proceed directly to CTPA)

In emergency settings, the PERC Rule (Pulmonary Embolism Rule-out Criteria) may also be utilized first to safely dismiss PE in very low-risk patients without any testing. For patients categorized as having an “unlikely” pre-test probability, a highly sensitive D-dimer blood test is performed; a negative result effectively rules out VTE.

D-dimer Testing

When a clot forms, it breaks down over time, releasing D-dimer into the bloodstream. This test measures the level of D-dimer, providing a quick and non-invasive initial assessment of venous thromboembolism (VTE) risk. High D-dimer levels suggest a recent clot formation, raising suspicion for venous thromboembolism (VTE). Normal D-dimer levels make venous thromboembolism (VTE) less likely, but not entirely ruled out.

D-dimer is a sensitive test, but not specific. Other conditions like infections or recent surgery can also elevate D-dimer levels.

Modern guidelines recommend utilizing age-adjusted D-dimer thresholds (calculated as age × 10 µg/L for patients over 50) to account for natural physiological increases and prevent false positives. Conversely, if a patient has a “likely” pre-test probability or an elevated D-dimer, definitive diagnostic imaging is mandated.

Compression Ultrasound

This is the gold standard for diagnosing deep vein thrombosis (DVT), the most common type of venous thromboembolism (VTE). Using sound waves, it creates a detailed image of the veins, revealing any blood clots obstructing the flow. It accurately identifies or excludes DVT in the legs, arms, or other areas. It is safe and non-invasive with minimal discomfort for the patient.

Additional Investigations

While D-dimer and compression ultrasound are the mainstays, other investigations may be needed in specific scenarios.

- Venography: This X-ray-based technique uses contrast dye to visualize the veins, offering a more comprehensive view but with higher radiation exposure.

- Blood Tests: Specific tests for inherited thrombophilias or other underlying conditions contributing to venous thromboembolism (VTE) risk may be ordered.

- CT Scan: For suspected pulmonary embolism (PE), a CT scan of the lungs can reveal blockages caused by clots traveling from the veins.

- Ventilation-Perfusion (V/Q) Scan: This specialized nuclear medicine test helps assess PE probability by looking at both air flow and blood flow in the lungs. Ventilation-Perfusion (V/Q) scan is reserved as the primary alternative for patients with strict contraindications to intravenous contrast, such as severe renal impairment or severe allergy. It can be helpful in inconclusive cases.

- Pulmonary angiography: A special type of X-ray test that requires insertion of a large catheter (a long, thin hollow tube) into a large vein (usually in the groin) and into the arteries within the lung, followed by injection of contrast material (dye) through the catheter.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): Uses radio waves and a magnetic field to provide images of the lung, but this test is usually reserved for certain patients, such as for pregnant women or in patients where the use of contrast material could be harmful.

- Computed tomographic pulmonary angiography (CTPA): A special type of X-ray test that includes injection of contrast material (dye) into a vein. For PE, Computed Tomography Pulmonary Angiography (CTPA) is the first-line imaging modality of choice to visualize occlusive filling defects within the pulmonary arterial tree

General Treatment and Management of VTE

The management of Venous Thromboembolism (VTE), comprising Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) and Pulmonary Embolism (PE), has evolved significantly. Modern treatment strategies emphasize outpatient management, the preferential use of Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs), and highly individualized durations of therapy based on the patient’s underlying hematological risk factors.

Phases of Anticoagulation Therapy

VTE treatment is conceptually divided into three distinct phases to manage acute risk and prevent long-term recurrence:

- Acute Phase (0 to 7-21 days): The immediate goal is to prevent thrombus extension and fatal PE. This phase requires rapid-acting anticoagulation, typically using a DOAC with a higher loading dose (e.g., Apixaban or Rivaroxaban) or parenteral therapy (Low Molecular Weight Heparin [LMWH] or Unfractionated Heparin [UFH]) bridging to a Vitamin K Antagonist (VKA) or another DOAC (e.g., Dabigatran or Edoxaban).

- Long-Term Phase (up to 3-6 months): The standard duration for completely treating the acute VTE event. The goal is to allow the body’s intrinsic fibrinolytic system to dissolve the clot while preventing early recurrence.

- Extended (Indefinite) Phase (Beyond 6 months): Secondary prevention for patients with a high risk of recurrence. The decision to continue therapy indefinitely weighs the risk of recurrent VTE against the cumulative risk of major bleeding.

Pharmacological Agent Selection

Current hematology and thrombosis guidelines strongly recommend DOACs over VKAs (like Warfarin) for the majority of patients lacking specific contraindications, due to their predictable pharmacokinetics, lower risk of intracranial hemorrhage, and lack of routine monitoring requirements.

DOAC Pharmacology and Reversal Summary

| Agent | Mechanism | Half-life (h) | Specific Reversal Agent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apixaban | Direct Factor Xa Inhibitor | 12 | Andexanet alfa |

| Rivaroxaban | Direct Factor Xa Inhibitor | 5–9 (young) / 11–13 (elderly) | Andexanet alfa |

| Edoxaban | Direct Factor Xa Inhibitor | 10–14 | Andexanet alfa (Off-label/Emerging) |

| Dabigatran | Direct Thrombin (IIa) Inhibitor | 12–17 | Idarucizumab |

- Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs): First-line for most unprovoked and provoked VTEs.

- Low Molecular Weight Heparin (LMWH): Preferred in: Pregnancy (as it does not cross the placenta) and historically the gold standard for Cancer-Associated Thrombosis (CAT).

- Vitamin K Antagonists (VKAs / Warfarin): Reserved for: Patients with severe renal impairment (CrCl < 15-30 mL/min), mechanical heart valves, and highly specific thrombophilias (see below).

Special Hematological Populations

For a hematology practice, tailoring anticoagulation to underlying pathologies is critical:

- Cancer-Associated Thrombosis (CAT): While LMWH was the traditional standard, major trials now support the use of DOACs (specifically Edoxaban, Rivaroxaban, and Apixaban) for CAT. DOACs should be used with extreme caution in patients with un-resected gastrointestinal or genitourinary malignancies due to a higher risk of mucosal bleeding; LMWH remains preferred in these scenarios.

- Antiphospholipid Syndrome (APS): DOACs are contraindicated in patients with triple-positive APS due to an unacceptably high rate of recurrent arterial thrombosis. Warfarin (target INR 2.0-3.0) remains the gold standard.

- Severe Thrombocytopenia: In patients with hematological malignancies or chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia (platelets < 50,000/μL), full-dose anticoagulation is often hazardous. Management typically involves LMWH dose reductions or, in severe cases, holding anticoagulation and considering a retrievable IVC filter.

Duration of Therapy: Provoked vs. Unprovoked

The decision to stop or continue anticoagulation after 3 to 6 months relies on the provoking factor:

- Transient/Reversible Risk Factor (e.g., Surgery, Trauma): High risk of initial clot, but low risk of recurrence. Anticoagulation is typically discontinued after 3 months.

- Persistent Risk Factor (e.g., Active Cancer): High continuous risk. Anticoagulation is continued indefinitely as long as the cancer is active or the patient is receiving anti-neoplastic therapy.

- Unprovoked VTE: High risk of recurrence (~30% at 5 years if anticoagulation is stopped). Most hematologists recommend extended/indefinite anticoagulation, often utilizing reduced-dose DOACs (e.g., Apixaban 2.5 mg BID or Rivaroxaban 10 mg daily) after the initial 6 months to minimize long-term bleeding risks.

Adjunctive and Advanced Therapies

- Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis (CDT): Considered for massive (hemodynamically unstable) PE, or highly symptomatic, extensive proximal DVT (e.g., iliofemoral DVT causing phlegmasia cerulea dolens) to rapidly reduce clot burden and save the limb.

- Inferior Vena Cava (IVC) Filters: Use is strictly limited to patients with an acute proximal DVT or PE who have an absolute contraindication to anticoagulation (e.g., active major bleeding, recent neurosurgery). Retrievable filters should be removed as soon as the bleeding risk resolves and anticoagulation can be safely initiated.

Prevention

For high-risk patients undergoing surgery, pregnancy, or other situations, prophylaxis plays a crucial role.

- Compression stockings: Improve blood flow and prevent clot formation.

- Early mobilization: Getting patients moving helps keep blood flowing smoothly.

- Blood thinners: Low-dose anticoagulants can be used in specific cases.

Remember

- Timely diagnosis and prompt treatment are essential for optimal outcomes.

- The choice of treatment depends on the type and severity of venous thromboembolism (VTE), individual risk factors, and patient preferences.

- Close monitoring and follow-up are crucial to ensure successful clot resolution and prevent recurrence.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the difference between DVT and VTE?

DVT (Deep Vein Thrombosis) is a specific type of VTE (Venous Thromboembolism).

- DVT is when a blood clot forms in a deep vein, usually in the leg or pelvis.

- VTE is a broader term that encompasses both DVT and pulmonary embolism (PE). PE occurs when a clot from a deep vein breaks off and travels to the lungs.

Essentially, all DVT cases are VTE, but not all VTE cases are DVT.

Which 2 conditions are forms of VTE?

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) are the two forms of VTE (Venous Thromboembolism).

What is the main cause of VTE?

The main cause of VTE (Venous Thromboembolism) is a combination of factors that disrupt normal blood flow and clotting. These factors include:

- Injury or surgery: Damage to veins can trigger clot formation.

- Immobility: Lack of movement allows blood to pool, increasing the risk of clots.

- Inflammation: Conditions like infections or inflammatory bowel disease can contribute to clot formation.

- Other risk factors: Obesity, age, certain medications, and genetic predispositions also play a role.

What happens if VTE is not treated?

If VTE is left untreated, it can lead to serious complications:

- Pulmonary embolism (PE): A portion of the clot can break loose and travel to the lungs, blocking blood flow and potentially causing death.

- Post-thrombotic syndrome: Damage to the veins caused by the clot can lead to long-term swelling, pain, and skin ulcers.

- Heart problems: A large PE can put significant strain on the heart, leading to heart failure.

What surgeries are high risk for VTE?

Surgeries with a high risk of VTE include:

- Orthopedic surgeries: Hip and knee replacements, femur fractures

- Major abdominal surgeries

- Pelvic surgeries

- Brain and spinal surgeries

- Major trauma

These surgeries often involve extended periods of immobility, which increases the risk of blood clots forming

What is the Wells Score for DVT and PE?

The Wells Score is a clinical risk assessment tool used by healthcare providers to estimate the probability that a patient has a DVT or PE. It assigns points to specific signs, symptoms, and risk factors (like active cancer, leg swelling, or heart rate). Based on the score, doctors decide whether to order a D-dimer blood test or proceed directly to imaging scans.

How are DOACs different from Warfarin for treating VTE?

Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs), such as apixaban and rivaroxaban, have largely replaced Warfarin as the first-line treatment for VTE. Unlike Warfarin, DOACs have fewer food and drug interactions, act much faster, and do not require routine blood test monitoring (INR tests).

Can a Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) be treated at home?

Yes. Thanks to the safety and ease of use of newer anticoagulant pills (DOACs) or low-molecular-weight heparin injections, many patients with stable, uncomplicated DVT can be safely treated at home without needing to be admitted to the hospital.

How long do I need to take blood thinners for a blood clot?

The duration of treatment depends on what caused the clot. If the VTE was “provoked” by a temporary risk factor (like surgery or trauma), treatment usually lasts for 3 months. If the VTE was “unprovoked” (happened without a clear cause) or is related to active cancer, anticoagulation may be extended for 6 months, a year, or even indefinitely to prevent recurrence.

What is an age-adjusted D-dimer test?

Because natural D-dimer levels slowly increase as we age, older patients often have “false positive” results on standard tests. To prevent unnecessary CT scans, doctors now use an “age-adjusted” cutoff for patients over 50 years old (calculated by multiplying the patient’s age by 10 µg/L).

Glossary of Related Medical Terms

- Anticoagulant: Often referred to as “blood thinners,” these medications (like heparin or DOACs) delay blood clotting, preventing new clots from forming and existing ones from growing.

- Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis (CDT): A minimally invasive procedure where a catheter delivers clot-dissolving medication directly into the thrombus.

- D-Dimer: A protein fragment produced when a blood clot dissolves in the body. Elevated levels indicate significant clot formation and breakdown.

- Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs): Modern anticoagulant medications that directly inhibit specific proteins in the clotting cascade (like Factor Xa or Thrombin) without requiring routine blood monitoring.

- Embolus: A piece of a blood clot, air bubble, or other object that breaks free, travels through the bloodstream, and lodges in a vessel, causing a blockage.

- Endothelium: The thin layer of cells lining the interior surface of blood vessels.

- Fibrinolysis: The body’s natural enzymatic process of breaking down the fibrin in blood clots.

- Hemostasis: The physiological process that stops bleeding at the site of an injury while maintaining normal blood flow elsewhere.

- Hypercoagulability (Thrombophilia): An inherited or acquired abnormality of the blood coagulation system that increases the risk of thrombosis.

- Post-Thrombotic Syndrome (PTS): A long-term complication of DVT characterized by chronic leg pain, swelling, heaviness, and skin changes due to venous valve damage.

- Thrombus: A solid mass of platelets and/or fibrin (and other cellular components) that forms locally in a vessel.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Saba HI, Roberts HR. Hemostasis and Thrombosis: Practical Guidelines in Clinical Management (Wiley Blackwell). 2014.

- DeLoughery TG. Hemostasis and Thrombosis 4th Edition (Springer). 2019.

- Keohane EM, Otto CN, Walenga JM. Rodak’s Hematology 6th Edition (Saunders). 2019.

- Kaushansky K, Levi M. Williams Hematology Hemostasis and Thrombosis (McGraw-Hill). 2017.

- https://www.hematology.org/education/clinicians/guidelines-and-quality-care/clinical-practice-guidelines/venous-thromboembolism-guidelines

- Lutsey, P. L., & Zakai, N. A. (2023). Epidemiology and prevention of venous thromboembolism. Nature reviews. Cardiology, 20(4), 248–262. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-022-00787-6

- Winter, M. P., Schernthaner, G. H., & Lang, I. M. (2017). Chronic complications of venous thromboembolism. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH, 15(8), 1531–1540. https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.13741

- Brill A. (2021). Multiple Facets of Venous Thrombosis. International journal of molecular sciences, 22(8), 3853. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22083853

- Saposnik, G., Bushnell, C., Coutinho, J. M., Field, T. S., Furie, K. L., Galadanci, N., Kam, W., Kirkham, F. C., McNair, N. D., Singhal, A. B., Thijs, V., Yang, V. X. D., & American Heart Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative and Resuscitation; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and Council on Hypertension (2024). Diagnosis and Management of Cerebral Venous Thrombosis: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Stroke, 55(3), e77–e90. https://doi.org/10.1161/STR.0000000000000456

- Smith, S. R. M., Morgan, N. V., & Brill, A. (2025). Venous thrombosis unchained: Pandora’s box of noninflammatory mechanisms. Blood advances, 9(12), 3002–3013. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2024014114