TL;DR

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are a group of clonal hematopoietic stem cell disorders characterized by ineffective hematopoiesis, resulting in peripheral blood cytopenias and a high risk of progression to Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML). Peak incidence > 70 years old.

- Causes ▾: Primarily sporadic/age-related (accumulation of somatic mutations). Secondary causes include prior chemotherapy or radiation (therapy-related MDS) and exposure to environmental toxins like benzene or tobacco smoke.

- Signs and symptoms ▾: Patients typically present with symptoms of bone marrow failure:

- Anemia: Fatigue, dyspnea, and pallor.

- Neutropenia: Recurrent or unusual infections.

- Thrombocytopenia: Easy bruising, petechiae, or mucosal bleeding.

- Key Laboratory Investigations ▾:

- CBC/PBF: Persistent cytopenias with dysplastic features (e.g., macrocytosis, hypogranular neutrophils, Pseudo-Pelger-Huët anomaly).

- Bone Marrow Aspirate/Biopsy: The “Gold Standard” to identify dysplasia in ≥10% of a cell lineage and to quantify blast percentages (<20%).

- Genetics: Cytogenetics (Karyotype) and NGS (Molecular testing) to identify defining mutations (e.g., SF3B1, del(5q), TP53) for classification and risk scoring (IPSS-M).

- Treatment & Management ▾: Tailored by risk stratification:

- Lower-Risk: Focuses on quality of life via supportive care (transfusions), Growth Factors (ESAs), Lenalidomide (for del(5q)), or Luspatercept (for ring sideroblasts).

- Higher-Risk: Aims to delay AML progression using Hypomethylating Agents (Azacitidine, Decitabine).

- Curative: Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation remains the only curative intent therapy for fit candidates.

*Click ▾ for more information

Introduction

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) encompass a diverse group of hematopoietic neoplasms caused by acquired mutations that disrupt the normal maturation of myeloid progenitors, leading to cytopenias in the peripheral blood. In myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), hematopoiesis is ineffective and the cells produced are often malformed or dysplastic. Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) is primarily confined to the elderly, with a peak incidence in individuals more than 70 years of age.

Myelodysplastic Syndrome (MDS) Symptoms

Most patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) present with vague symptoms related to the slow onset of anemia, neutropenia, or thrombocytopenia as the disease progression is not acute.

Anemia can manifest as fatigue, shortness of breath, pale skin, and dizziness. Additionally, patients may experience easy bruising and excessive bleeding due to a lack of functional platelets. In severe cases, recurrent infections may occur as a consequence of neutropenia.

Some other myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) individuals may experience vague, non-specific symptoms such as weight loss, fatigue, and fever. These seemingly trivial symptoms, when considered in conjunction with other factors like age and family history, can raise suspicion of underlying myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS).

Causes Related to Myelodysplastic Syndrome (MDS)

Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) arises sporadically, but some cases are related to exposure to DNA-damaging agents. While the exact mechanisms are still under investigation, several key contributors have emerged as leading suspects.

- Acquired genetic mutations: The most significant culprit in myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) is the presence of acquired genetic mutations within blood stem cells. These mutations disrupt the normal process of blood cell development, leading to abnormal and dysfunctional cells. Age is a major risk factor for acquiring these mutations, as the accumulation of genetic errors over time increases the likelihood of developing myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS).

- Exposure to certain toxins and chemicals: Certain environmental exposures have been linked to an increased risk of developing myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). These include:

- Benzene: A chemical found in gasoline and tobacco smoke

- Pesticides and herbicides: Commonly used in agriculture and gardening

- Radiation: Exposure to high doses of radiation, such as during cancer treatment

- Previous cancer treatment: Individuals who have undergone chemotherapy or radiation therapy for other cancers are at a higher risk of developing myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) as a secondary complication. This risk is related to the damage these treatments can inflict on bone marrow and blood stem cells.

- Certain inherited conditions: While uncommon, some genetic disorders can increase the risk of developing myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). These include Fanconi anemia, Diamond-Blackfan anemia, and Shwachman-Diamond syndrome.

- Smoking: Tobacco smoking is a well-established risk factor for various cancers, and it is also associated with an increased risk of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). This is likely due to the presence of harmful chemicals in tobacco smoke that can damage DNA and contribute to the development of cancer and other blood disorders.

- Unknown factors: In many cases, the specific cause of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) remains elusive. Several other factors, such as dietary deficiencies, autoimmune disorders, and viral infections, are being investigated for their potential role in the development of this disease.

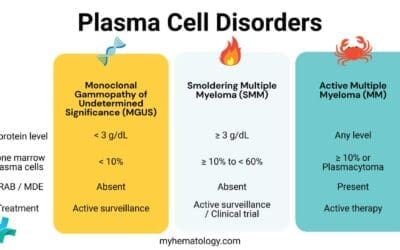

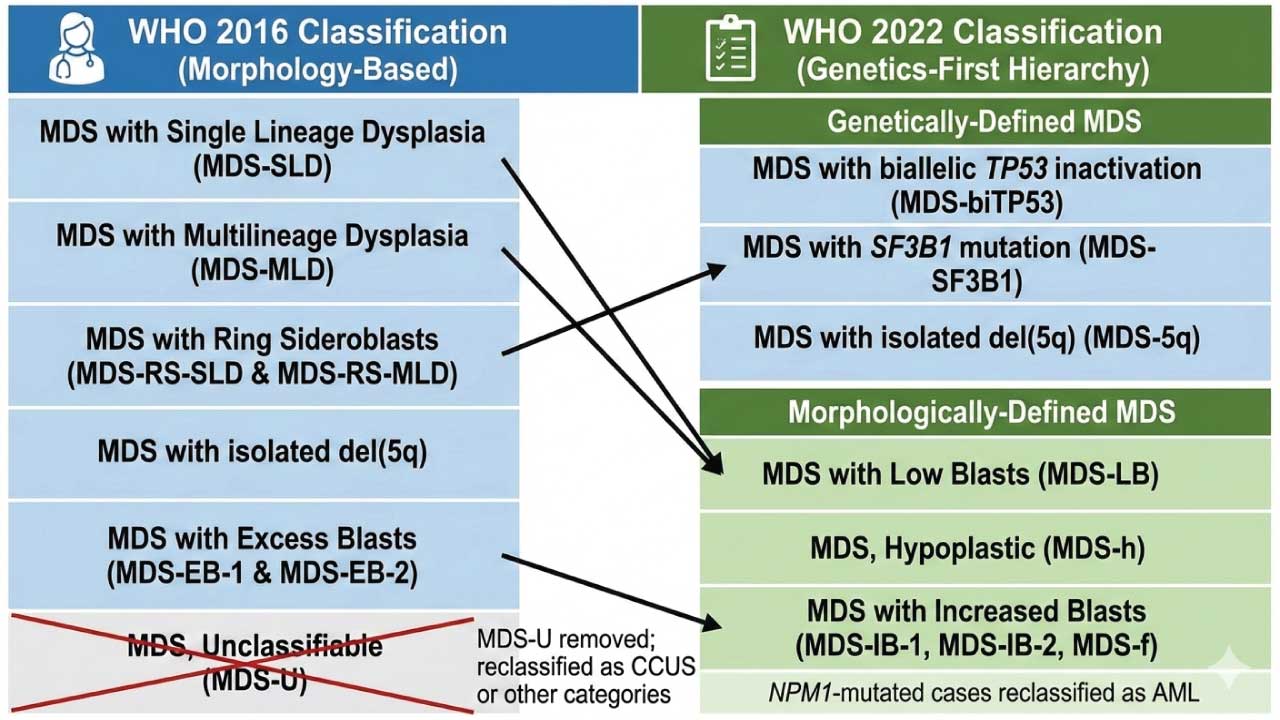

WHO Classifications of Myelodysplastic Syndrome (MDS)

The 2022 WHO Classification (5th Edition) represents a paradigm shift in how we approach Myelodysplastic Syndromes, now officially renamed Myelodysplastic Neoplasms (MDS) to emphasize their neoplastic nature. The primary change is the creation of a hierarchy that prioritizes genetically-defined entities over traditional morphological ones.

The classification now splits MDS into two main “branches.” If a patient has one of the three “defining genetic abnormalities,” they are classified accordingly, regardless of the number of dysplastic lineages. If they do not, the diagnosis relies on morphology (blast count and cellularity).

Genetically-Defined MDS

These categories take precedence. Even if a patient has multilineage dysplasia, they are “pulled” into these specific buckets:

- MDS with biallelic TP53 inactivation (MDS-biTP53): A critical new addition. It requires two or more TP53 mutations, or one mutation with evidence of loss of the other allele (e.g., 17p deletion or VAF > 50%). This subtype carries the poorest prognosis and often presents with a complex karyotype.

- MDS with SF3B1 mutation (MDS-SF3B1): This replaces “MDS with Ring Sideroblasts.” The focus is now on the mutation rather than the physical iron rings, though ≥ 15% ring sideroblasts can still be used as a surrogate if the SF3B1 mutation is absent.

- MDS with isolated del(5q) (MDS-5q): Remains similar to the 2016 version but now requires checking for TP53 mutations, as the presence of a TP53 mutation (even monoallelic) may change the management and risk profile.

Morphologically-Defined MDS

If no defining genetic abnormality is found, the disease is categorized by blast counts and marrow cellularity:

- MDS with Low Blasts (MDS-LB): Replaces the previous “Single Lineage” and “Multilineage” dysplasia categories. It is defined by < 5% blasts in the marrow and < 2% in the blood.

- MDS, Hypoplastic (MDS-h): Now recognized as a distinct entity. It requires bone marrow cellularity < 25% (age-adjusted) and is often associated with an immune-mediated pathophysiology, sometimes responding to immunosuppressive therapy.

- MDS with Increased Blasts (MDS-IB): Replaces the term “Excess Blasts.”

- MDS-IB1: 5–9% BM blasts or 2–4% PB blasts.

- MDS-IB2: 10–19% BM blasts or 5–19% PB blasts (or the presence of Auer rods).

- MDS with Fibrosis (MDS-f): A new entity for cases with increased blasts that also exhibit Grade 2 or 3 fibrosis. This subtype is associated with a more aggressive course and worse survival.

Laboratory Investigations Related to MDS

Initial Screening

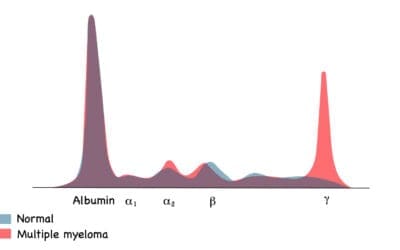

The diagnostic journey always begins with a Complete Blood Count (CBC) and a Peripheral Blood Film (PBF).

- Persistent Cytopenias: Defined by the WHO as Anemia (Hb <12 – 13 g/dL), Neutropenia (ANC <1.8 × 109/L), or Thrombocytopenia (Plt <150 × 109/L) lasting at least 4 – 6 months.

- Macrocytosis: An elevated MCV (often >100 fL) with macro-ovalocytes is a classic early sign.

- Dysgranulopoiesis: Look for the Pseudo-Pelger-Huët anomaly (hyposegmented, bilobed, or “pince-nez” nuclei) and hypogranular neutrophils.

- Blasts: The presence of even 1% blasts in the peripheral blood is a red flag for higher-risk MDS.

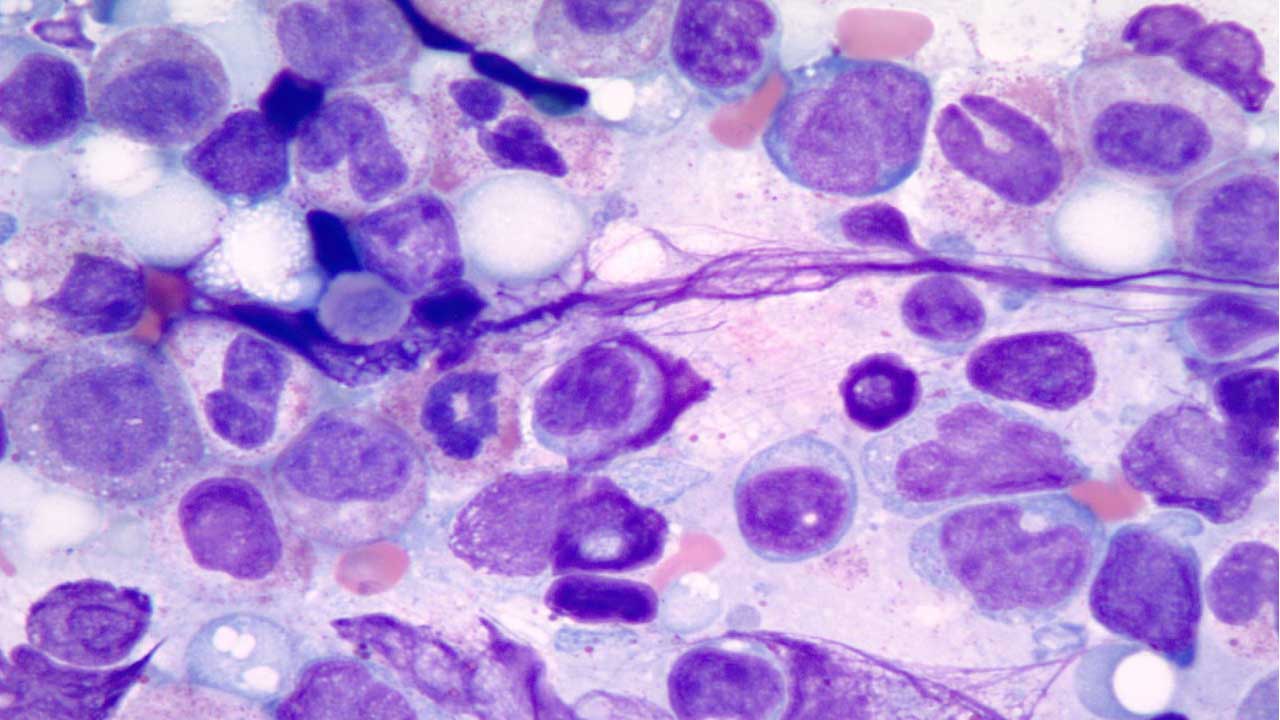

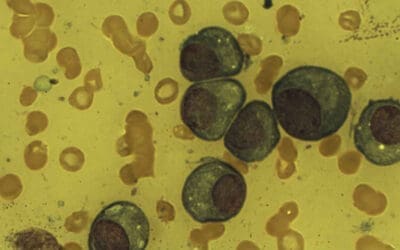

The Gold Standard: Bone Marrow (BM) Evaluation

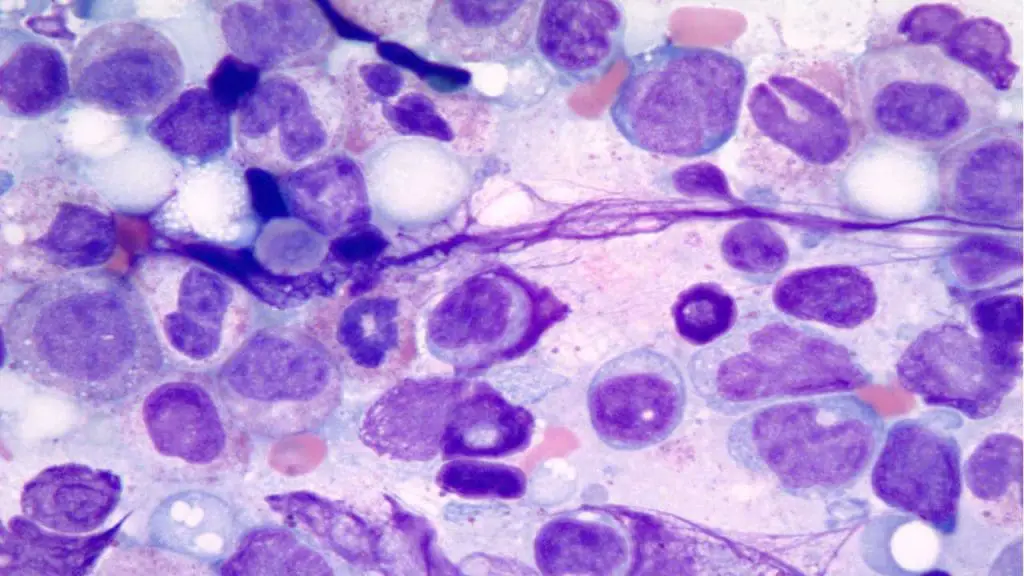

A bone marrow aspirate and trephine biopsy are mandatory to confirm the diagnosis and exclude mimics.

- Morphological Dysplasia: Requires ≥ 10% of cells in at least one lineage (Erythroid, Myeloid, or Megakaryocytic) to show dysplastic features.

- Erythroid: Nuclear budding, internuclear bridging, or ring sideroblasts.

- Myeloid: Hyposegmentation and abnormal granulation.

- Megakaryocytic: Micromegakaryocytes (small cells with single or pawn-broker nuclei) are the most specific markers for MDS.

- Prussian Blue (Iron) Stain: Essential for identifying ring sideroblasts (mitochondrial iron encircling ≥ 1/3 of the nucleus).

- Blast Quantification: Crucial for distinguishing MDS from AML (cutoff < 20% blasts).

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC): CD34 staining is used to identify clusters of immature precursors (ALIP—Abnormal Localization of Immature Precursors), which suggests a higher risk of transformation.

Advanced Genetic & Molecular Profiling

A diagnosis is considered incomplete without molecular data.

- Conventional Karyotyping: Identifies large chromosomal shifts like del(5q), trisomy 8, or monosomy 7. About 50% of MDS patients have a normal karyotype, making molecular testing vital.

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): Now used to detect mutations in a “myelid panel” of genes.

- Diagnostic: Mutations in SF3B1, ASXL1, or TET2 support a clonal diagnosis.

- Prognostic: Mutations in TP53 (especially biallelic) or RUNX1 signify an aggressive course.

- The IPSS-M Score: Unlike the older IPSS-R, the Molecular IPSS integrates these NGS findings with clinical data to provide the most accurate risk stratification available today.

Ancillary & Exclusionary Tests

MDS is a “diagnosis of exclusion.” You must rule out nutritional and toxic causes of dysplasia:

- Vitamin B12 and Folate Deficiency: Deficiency can perfectly mimic MDS morphology (megaloblastic madness).

- Copper Levels: Copper deficiency (often due to excessive zinc intake) causes vacuolation of precursors and ring sideroblasts.

- Reticulocyte Count: Usually low in MDS, reflecting the ineffective hematopoiesis (the marrow is full, but it can’t release healthy cells).

- Flow Cytometry: While not always mandatory for diagnosis, it helps identify aberrant immunophenotypes (e.g., loss of CD13/CD11b or gain of CD7 on myeloid cells) which support a diagnosis in “morphologically borderline” cases.

Prognosis of Myelodysplastic Syndrome (MDS)

The Molecular International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS-M) is the current gold standard for risk-stratifying patients with Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS). Developed by the International Working Group for Prognosis in MDS (IWG-PM), it successfully bridges the gap between traditional morphology and modern genomics.

While the older IPSS-R (Revised) relied solely on blood counts and chromosomes, the IPSS-M integrates the mutational status of 31 genes, significantly improving the accuracy of survival and leukemia transformation predictions.

The Three Pillars of IPSS-M

To calculate an IPSS-M score, three distinct types of data are required:

- Clinical Parameters:

- Hemoglobin level (g/dL)

- Platelet count (× 109/L)

- Bone marrow blast percentage (%)

- Cytogenetic Risk: The 5-tier cytogenetic risk category established by the IPSS-R (Very Good, Good, Intermediate, Poor, Very Poor).

- Molecular Data (NGS): The presence, number, and Variant Allele Frequency (VAF) of mutations in 31 specific genes. Notably, it distinguishes between “single-hit” and “multi-hit” (biallelic) TP53 mutations.

The 31 Genes of the IPSS-M

These genes are selected for their independent impact on prognosis. For clinical purposes, they are often grouped by their biological function:

| Functional Group | Key Genes Included |

| Splicing Factors | SF3B1, SRSF2, U2AF1, ZRSR2 |

| Epigenetic Regulators | TET2, DNMT3A, ASXL1, IDH1/2, EZH2 |

| Transcription Factors | RUNX1, ETV6, GATA2, CEBPA |

| Signaling/Pro-growth | NRAS, KRAS, JAK2, FLT3, PTPN11, CBL |

| Tumor Suppressors | TP53 (Biallelic/Multi-hit status is key) |

| Other Drivers | STAG2, BCOR, PHF6, PRPF8, NPM1 |

The 6 Risk Strata

The IPSS-M provides a continuous score that translates into six distinct risk categories. This is a more refined “resolution” than the 5 categories of the IPSS-R.

- Very Low

- Low

- Moderate Low

- Moderate High

- High

- Very High

The primary value of the IPSS-M is its ability to re-stratify patients. Studies have shown that approximately 46% of patients are assigned a different risk category when moving from IPSS-R to IPSS-M.

- Upstaging: About 24% of patients are moved to a higher risk group (e.g., from Low to Moderate High) because a “hidden” mutation (like TP53 or ASXL1) was found.

- Downstaging: About 22% are moved to a lower risk group, often when an SF3B1 mutation is found without other high-risk markers.

- Younger Patients: IPSS-M is significantly better at predicting outcomes for patients under 60 years of age, where blood counts alone often fail to reflect the aggressive nature of the underlying clones.

Myelodysplastic Syndrome (MDS) Treatment

The management of Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS) is highly personalized, guided primarily by the patient’s IPSS-M risk score, age, and performance status. The therapeutic goal is a “fork in the road”: for lower-risk patients, the focus is on hematologic improvement (improving quality of life); for higher-risk patients, the focus is on modifying the natural history of the disease and delaying progression to AML.

Management of Lower-Risk MDS

The main clinical challenge in lower-risk MDS is chronic anemia.

- Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agents (ESAs): (e.g., Epoetin alfa, Darbepoetin). These are the first-line treatment for symptomatic anemia, provided the endogenous serum erythropoietin (EPO) level is <500 U/L.

- Luspatercept: A first-in-class erythroid maturation agent. It is specifically used for patients with MDS with Ring Sideroblasts (MDS-SF3B1) who have failed ESAs or are unlikely to respond.

- Lenalidomide: The standard of care for patients with MDS-5q. It can induce transfusion independence in over 60% of these cases and can even lead to complete cytogenetic remission.

- Immunosuppressive Therapy (IST): In a subset of younger patients with hypoplastic MDS, treatment with Antithymocyte Globulin (ATG) and Cyclosporine can yield responses by targeting the T-cell-mediated destruction of stem cells.

Management of Higher-Risk MDS

In higher-risk cases, the marrow is progressively failing, and the risk of leukemia is imminent.

- Hypomethylating Agents (HMAs): Azacitidine and Decitabine are the backbone of therapy. They work by restoring normal gene expression. Azacitidine is specifically noted for showing an overall survival benefit in randomized trials.

- HMA + Venetoclax: Borrowing from AML protocols, the combination of an HMA with the BCL-2 inhibitor Venetoclax is increasingly used in fit, higher-risk MDS patients to achieve deeper remissions.

- Intensive Chemotherapy: High-dose “7+3” style chemotherapy is generally reserved for fit, younger patients with a high blast count, primarily as a “bridge” to clear the marrow before a stem cell transplant.

The Only Curative Option: Allogeneic HSCT

Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (allo-HSCT) remains the only curative therapy for MDS. For lower-risk patients, transplant is usually delayed to avoid the high morbidity/mortality of the procedure. For higher-risk patients (Intermediate to Very High), transplant is pursued as early as possible once a donor is found.

Supportive Care (Universal Approach)

Regardless of the risk group, all MDS patients require robust supportive care:

- Transfusion Support: Judicious use of packed red cells and platelets.

- Iron Chelation: Chronic transfusions lead to secondary iron overload (hemosiderosis). Agents like Deferasirox or Deferoxamine are used to prevent end-organ damage (heart/liver) in patients with a long life expectancy.

- Antibiotic Prophylaxis: In patients with severe, persistent neutropenia, prophylactic anti-infectives may be necessary.

Targeted Therapies

With the rise of NGS, we now treat specific mutations:

- IDH1/IDH2 Inhibitors: (e.g., Ivosidenib, Enasidenib). These are used off-label or in trials for patients harboring these specific mutations.

- Magrolimab: A CD47-targeting antibody (“don’t eat me” signal inhibitor) currently being studied, particularly in the difficult-to-treat TP53-mutated population.

Treatment by Risk Category

| Risk Group | Primary Goal | First-Line Options |

| Very Low / Low | Symptom control | ESAs, Lenalidomide (5q-), Luspatercept (RS), IST |

| Moderate | Delay progression | HMAs or clinical trials |

| High / Very High | Survival / Cure | HMAs, HSCT, Intensive Chemotherapy |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Is myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) cancer curable?

Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) is not typically curable. However, there are treatments available that can manage the symptoms, improve quality of life, and, in some cases, slow down the progression of the disease.

Stem cell transplant is often considered the most promising myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) treatment, as it can potentially replace the damaged bone marrow with healthy cells. However, it is not suitable for everyone due to the risks involved.

What is the life expectancy of a person with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)?

The life expectancy of a person with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) varies greatly depending on several factors, including:

- Type of MDS: Some types of MDS are more aggressive than others.

- Stage of the disease: The earlier the MDS is diagnosed, the better the prognosis.

- Overall health: Other underlying health conditions can affect life expectancy.

- Treatment response: How well the individual responds to treatment can significantly impact their outlook.

It’s important to note that while myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) can be a serious condition, there are advancements in treatment options that can improve quality of life and extend survival.

What organ does myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) affect?

Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) primarily affects the bone marrow. The bone marrow is responsible for producing blood cells, including red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets. In myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), the bone marrow becomes damaged and is unable to produce enough healthy blood cells. This can lead to a variety of symptoms, including fatigue, anemia, bleeding, and infections.

What are signs that MDS is progressing?

Here are some signs that MDS may be progressing:

- Increasing anemia: This can lead to more severe fatigue, weakness, and shortness of breath.

- Frequent infections: A weakened immune system due to low white blood cell count can increase the risk of infections.

- Excessive bleeding: This can occur due to low platelet count and may manifest as easy bruising, nosebleeds, or bleeding gums.

- Bone pain: As MDS progresses, the damaged bone marrow can cause pain in the bones.

- Enlarged spleen or liver: These organs may become enlarged as the body tries to compensate for the damaged bone marrow.

Is myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) an aggressive cancer?

Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) can be aggressive, but it’s not always. The aggressiveness of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) varies depending on the specific type and stage of the disease. Some forms of MDS progress slowly, while others can be more rapidly aggressive.

What is the difference between MDS and AML?

The primary distinction is the “blast count” in the bone marrow. MDS is characterized by fewer than 20% blasts, while 20% or more typically signifies a transition to Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML).

What is the “MDS-biTP53” subtype?

Introduced in the 2022 WHO classification, this refers to MDS with biallelic TP53 mutations. It is associated with a very high risk of progression and poor response to standard chemotherapy.

Why is my bone marrow “full” (hypercellular) if my blood counts are low?

This is due to “ineffective hematopoiesis.” The bone marrow produces many cells, but they are defective and undergo programmed cell death (apoptosis) before entering the bloodstream.

Does everyone with MDS need chemotherapy?

No. Lower-risk patients often start with “watch and wait” or supportive care (transfusions and growth factors), while chemotherapy and HMAs are reserved for higher-risk categories.

Glossary of Related Medical Terms

- Aplasia: The failure of an organ or tissue to develop or function normally; in hematology, it refers to the disappearance of blood-cell-forming tissue in the bone marrow.

- Apoptosis: Programmed cell death. In MDS, “ineffective hematopoiesis” occurs because blood precursors undergo excessive apoptosis within the marrow.

- Auer Rod: Needle-like cytoplasmic inclusions seen in myeloid blasts; their presence in MDS automatically classifies the disease as high-risk (MDS-EB2).

- Blast Cell: An immature precursor cell. In healthy marrow, blasts make up <5%; in MDS, they are <20%; at ≥20%, the disease is classified as Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML).

- Clonal Disorder: A condition where a population of cells is derived from a single mutated parent cell, sharing the same genetic abnormalities.

- Cytopenia: A reduction in the number of mature blood cells. Common forms include anemia (low RBCs), neutropenia (low WBCs), and thrombocytopenia (low platelets).

- Dacryocyte: Also known as a “teardrop cell,” these are red blood cells shaped like tears, commonly seen in the peripheral blood of patients with Primary Myelofibrosis.

- Dysplasia: Abnormalities in the size, shape, and organization of mature cells. This is the morphological hallmark of MDS.

- Epigenetics: Changes in organisms caused by modification of gene expression (like DNA methylation) rather than alteration of the genetic code itself.

- Hematopoiesis: The process by which the body produces new blood cells.

- Hypomethylating Agents (HMAs): A class of drugs (e.g., Azacitidine) that helps “turn back on” genes that prevent cancer growth by removing methyl groups from DNA.

- IPSS-M (Molecular IPSS): The latest risk-stratification tool that combines clinical data (blood counts) with molecular data (gene mutations) to predict MDS outcomes.

- Leukoerythroblastosis: The presence of immature white blood cells and nucleated red blood cells in the peripheral blood, often indicating marrow “stress” or infiltration.

- Lineage: The “family tree” of a blood cell (e.g., Erythroid for red cells, Myeloid for white cells, Megakaryocytic for platelets).

- Myelophthisis: The displacement of hemopoietic bone marrow tissue by fibrosis, tumors, or granulomas.

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): A modern lab technique used to rapidly sequence DNA and identify the specific somatic mutations (like SF3B1 or TP53) driving MDS.

- Pancytopenia: A clinical state where all three mature blood cell lines (RBCs, WBCs, and Platelets) are abnormally low.

- Ring Sideroblast: An erythroblast (RBC precursor) with a “necklace” of iron-laden mitochondria surrounding the nucleus, a diagnostic marker for specific MDS subtypes.

- Somatic Mutation: A genetic alteration acquired by a cell that was not inherited from parents; these mutations are the primary cause of “acquired” MDS.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Greenberg PL, Tuechler H, Schanz J, Sanz G, Garcia-Manero G, Solé F, Bennett JM, Bowen D, Fenaux P, Dreyfus F, Kantarjian H, Kuendgen A, Levis A, Malcovati L, Cazzola M, Cermak J, Fonatsch C, Le Beau MM, Slovak ML, Krieger O, Luebbert M, Maciejewski J, Magalhaes SM, Miyazaki Y, Pfeilstöcker M, Sekeres M, Sperr WR, Stauder R, Tauro S, Valent P, Vallespi T, van de Loosdrecht AA, Germing U, Haase D. Revised international prognostic scoring system for myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2012 Sep 20;120(12):2454-65. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-420489. Epub 2012 Jun 27. PMID: 22740453; PMCID: PMC4425443.

- Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, Thiele J, Borowitz MJ, Le Beau MM, Bloomfield CD, Cazzola M, Vardiman JW. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016 May 19;127(20):2391-405. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544. Epub 2016 Apr 11. PMID: 27069254.

- Garcia-Manero G. Myelodysplastic syndromes: 2023 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2023 Aug;98(8):1307-1325. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26984. Epub 2023 Jun 8. PMID: 37288607.

- Hadley A. Myelodysplastic Syndrome (MDS): A guide for MDS (symptoms, prognosis and common treatment options) (Understanding Your immune system). (2020).

- Gotlib J, Fechter L. 100 Questions & Answers About Myelodysplastic Syndromes. (2015).

- Thomas JT. Myelodysplastic Syndrome: Fast Focus Study Guide. (2015).

- Kröger N. (2025). Treatment of high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Haematologica, 110(2), 339–349. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2023.284946

- Merz, A. M. A., & Platzbecker, U. (2025). Treatment of lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Haematologica, 110(2), 330–338. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2023.284945

- Garcia, J. S., Kim, H. T., Murdock, H. M., Ansuinelli, M., Brock, J., Cutler, C. S., Gooptu, M., Ho, V. T., Koreth, J., Nikiforow, S., Romee, R., Shapiro, R., DeAngelo, D. J., Stone, R. M., Bat-Erdene, D., Ryan, J., Contreras, M. E., Fell, G., Letai, A., Ritz, J., … Antin, J. H. (2024). Prophylactic maintenance with venetoclax/azacitidine after reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic transplant for high-risk MDS and AML. Blood advances, 8(4), 978–990. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2023012120

- McMahon, C., Raddi, M. G., Mohan, S., & Santini, V. (2025). New Approvals in Low- and Intermediate-Risk Myelodysplastic Syndromes. American Society of Clinical Oncology educational book. American Society of Clinical Oncology. Annual Meeting, 45(3), e473654. https://doi.org/10.1200/EDBK-25-473654