TL;DR

Eosinophilia (high eosinophils), defined as an elevated eosinophil count above 500 cells/µL, is a laboratory finding, not a disease itself, that signals a potential underlying medical issue requiring investigation based on its severity and the patient’s symptoms.

Causes ▾:

- Allergies

- Infections (parasitic, fungal)

- Asthma

- Certain medications

- Autoimmune disorders

- Some cancers

Symptoms ▾:

Vary widely depending on the cause and organs involved.

- Skin rashes, itching

- Respiratory issues (cough, wheezing)

- Digestive problems

- Fatigue

- Nasal congestion

Laboratory Investigations ▾:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) with differential (high eosinophil count)

- Stool examination (for parasites)

- Allergy testing

- Imaging (X-rays, CT scans)

- Biopsies (of affected tissues)

- Bone marrow aspiration (in some cases)

Treatment ▾:

- Treat underlying cause (e.g., antihistamines for allergies, anti-parasitics for infections)

- Corticosteroids (to reduce inflammation)

- Other medications depending on the specific condition

*Click ▾ for more information

Introduction

While not always the primary presenting complaint, eosinophilia (hight eosinophils) is a frequently observed laboratory abnormality. It can be identified during routine blood work or as part of the investigation of various symptoms. It serves as an important indicator that warrants further investigation to identify the underlying etiology, which can range from benign allergic reactions to significant systemic disorders.

What are Eosinophils?

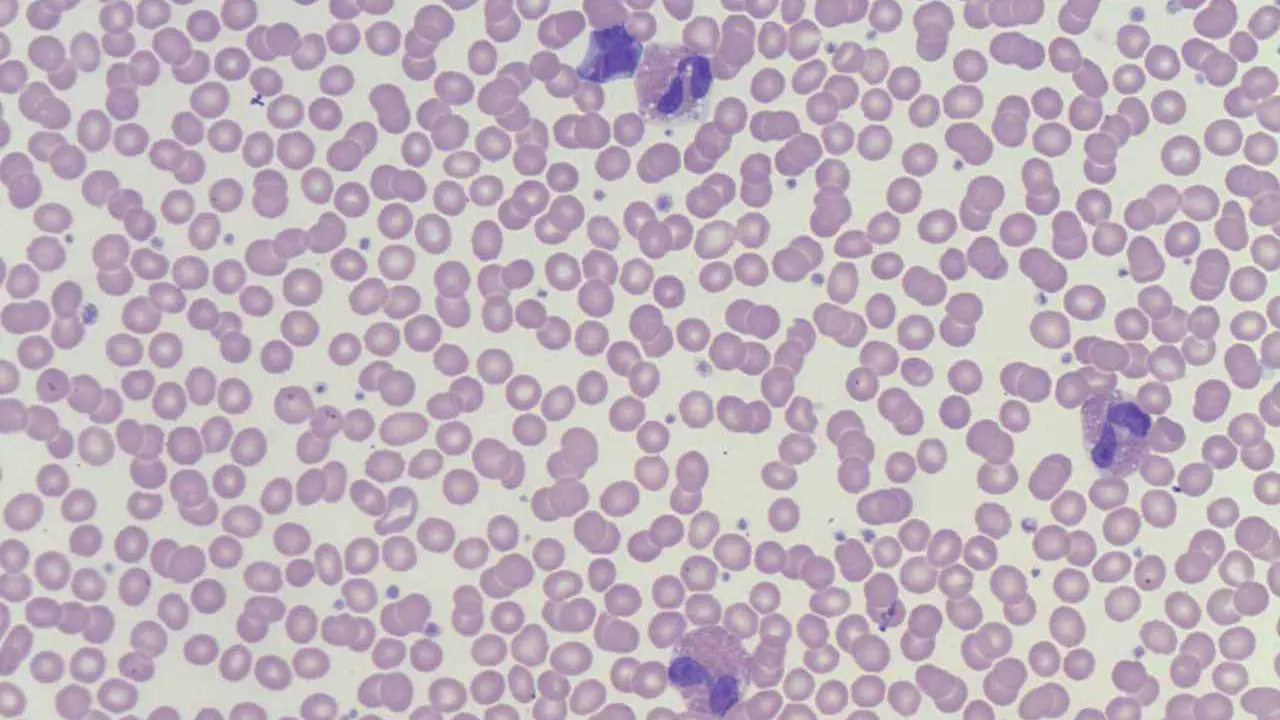

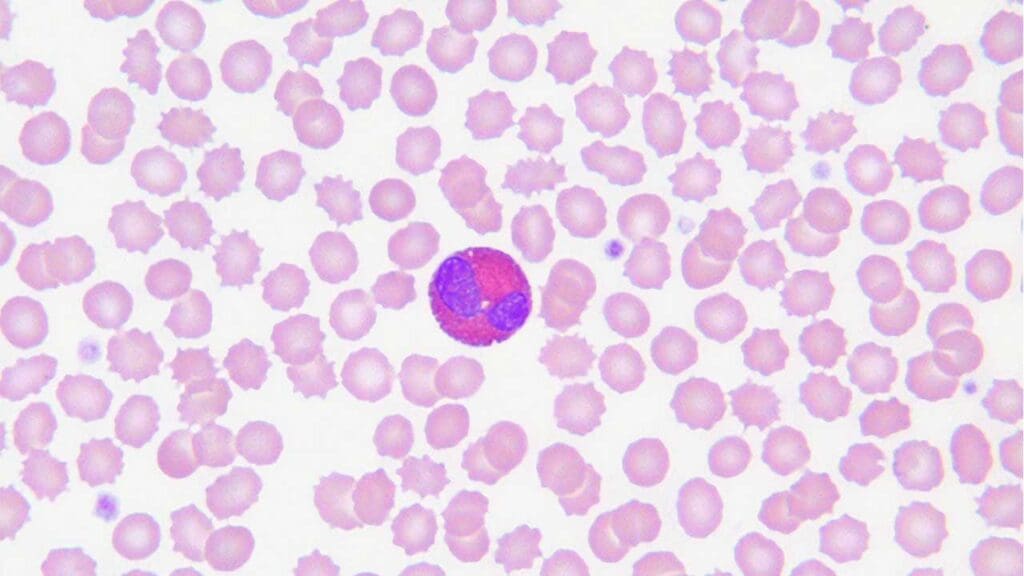

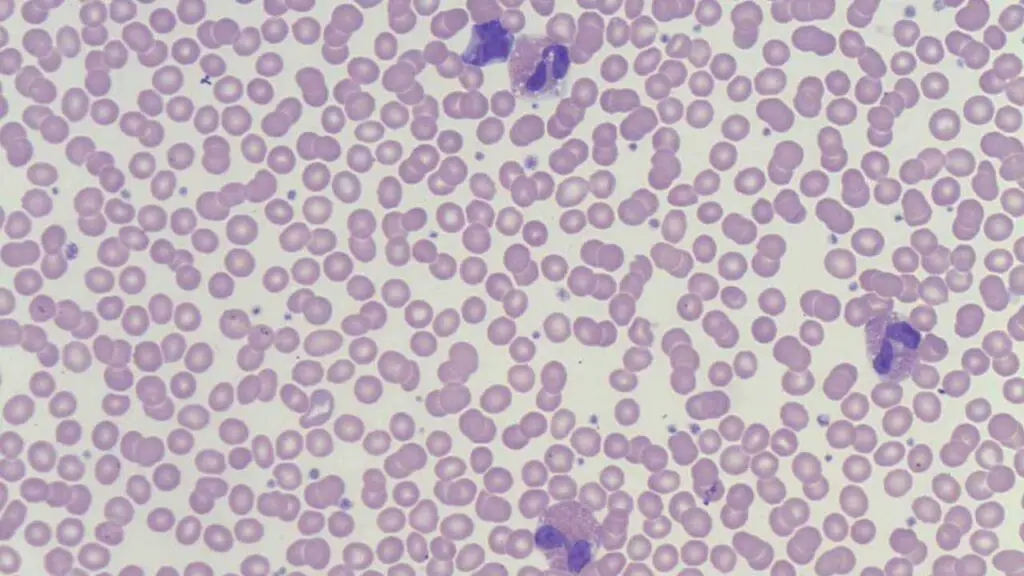

Eosinophils are a type of white blood cell, specifically a granulocyte, that plays a role in the immune system. They are characterized by their cytoplasmic granules that stain bright pink or red with eosin dye under a microscope. Eosinophils are particularly known for their involvement in defending against parasitic infections and mediating allergic reactions.

What is a normal eosinophil count?

A normal eosinophil count in peripheral blood is typically considered to be less than 500 cells per microliter (µL) or less than 0.5 x 10⁹/L. Please refer to the specific reference range provided by the laboratory that performed the blood test as there can be slight variations in the reference range between laboratories.

What is Eosinophilia (High Eosinophils)?

Eosinophilia is a condition characterized by a higher-than-normal number of eosinophils in the peripheral blood. Specifically, it is generally defined as an absolute eosinophil count of more than 500 cells per microliter (µL) or 0.5 x 10⁹/L.

Eosinophilia (high eosinophils) itself is not a disease but rather a laboratory finding that can indicate an underlying medical condition. The significance and need for further investigation depend on the degree of eosinophilia (high eosinophils) and the individual’s clinical presentation.

Causes of Eosinophilia

Eosinophilia (high eosinophils) is a multifaceted finding with a broad range of underlying etiologies.

Allergic and Hypersensitivity Reactions

While the immediate symptoms of an allergic reaction are primarily driven by mast cell and basophil degranulation, eosinophils play a crucial role in the late-phase reaction and the chronic inflammatory processes associated with allergic diseases. Their involvement contributes significantly to tissue damage and the persistence of allergic symptoms.

The pathophysiology of eosinophilia (high eosinophils) is primarily driven by the Th2-mediated immune response. Upon exposure to an allergen, antigen-presenting cells activate Th2 helper T cells, which subsequently release cytokines such as interleukin-4 (IL-4), interleukin-5 (IL-5), and interleukin-13 (IL-13). IL-4 promotes IgE class switching in B cells, leading to the production of allergen-specific IgE antibodies that bind to mast cells and basophils.

Upon re-exposure to the allergen, cross-linking of these IgE antibodies triggers the release of preformed mediators (like histamine) and newly synthesized mediators (like leukotrienes and prostaglandins) from mast cells and basophils, contributing to immediate hypersensitivity symptoms.

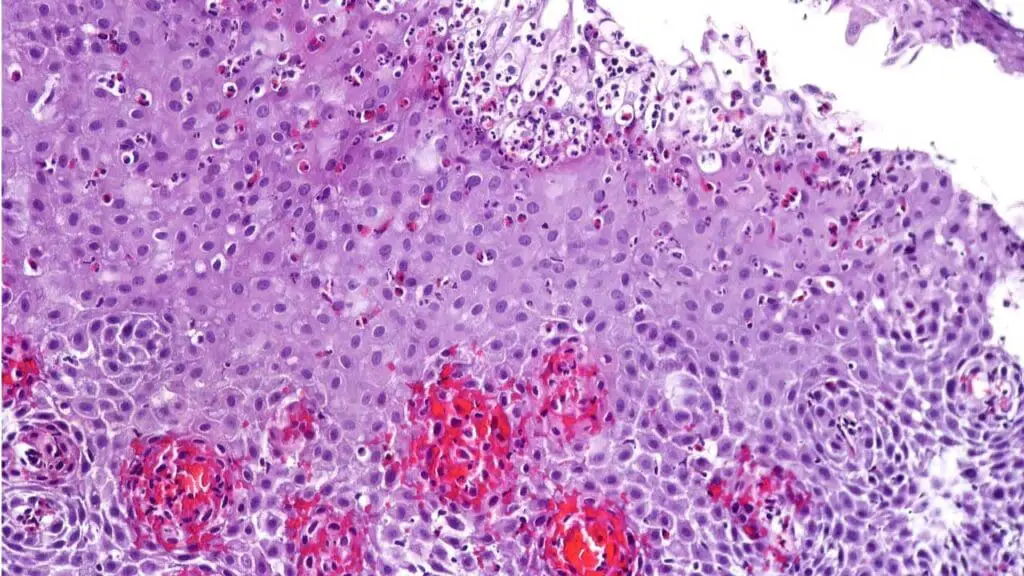

Crucially, IL-5 acts as a potent chemoattractant and survival factor for eosinophils, leading to their increased production in the bone marrow, recruitment to the site of allergic inflammation, and prolonged survival. Once activated, eosinophils release a variety of cytotoxic granular proteins (like major basic protein, eosinophil cationic protein, eosinophil peroxidase, and eosinophil-derived neurotoxin) and lipid mediators, which contribute to tissue damage, inflammation, and the characteristic symptoms of allergic diseases.

Common Examples

- Asthma: Often associated with airway inflammation involving eosinophils, contributing to bronchoconstriction and mucus production. Sputum and bronchial biopsies from patients with allergic asthma often show a significant increase in eosinophil numbers. The degree of eosinophilic inflammation can correlate with asthma severity and responsiveness to certain treatments (e.g., corticosteroids, anti-IL-5 biologics).

- Allergic Rhinitis and Conjunctivitis: Inflammation of the nasal passages and conjunctiva due to airborne allergens. Nasal smears from patients with allergic rhinitis often reveal an increased number of eosinophils during symptomatic periods.

- Eczema (Atopic Dermatitis): Chronic inflammatory skin condition with eosinophilic infiltration in the skin lesions. Skin biopsies from eczematous lesions often show a significant infiltration of eosinophils. The level of eosinophilia (high eosinophils) in the skin can correlate with disease severity. Systemic eosinophilia (high eosinophils) can also be present in severe cases.

- Drug Reactions: Certain medications can trigger hypersensitivity reactions leading to eosinophilia (high eosinophils). This can range from mild skin rashes to severe systemic reactions. Peripheral blood eosinophilia (high eosinophils) is a common finding in many drug hypersensitivity reactions, especially DRESS syndrome, where it is a key diagnostic criterion. Tissue biopsies of affected organs can also show eosinophilic infiltration.

- Food Allergies: Immune responses to specific food proteins can result in eosinophilia (high eosinophils), sometimes with gastrointestinal symptoms. Biopsies of the esophagus, stomach, or intestines in patients with suspected food allergies and GI symptoms often show a high number of eosinophils, which is crucial for diagnosis. Peripheral blood eosinophilia (high eosinophils) may also be present.

Infectious Diseases

Eosinophils play a significant role in the defense against certain pathogens, particularly helminthic (worm) parasites. They release cytotoxic granules that can damage the parasite.

The presence of the parasite, especially helminths, stimulates a Th2-biased immune response, leading to the release of cytokines like IL-5, which promotes eosinophil production, maturation, and recruitment to the site of infection.

Eosinophils then attempt to eliminate the parasite through the release of cytotoxic granular proteins, such as major basic protein and eosinophil cationic protein, and by antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity.

While beneficial in controlling certain infections, the eosinophilic response can also contribute to tissue damage and inflammation in the affected organs. In some fungal infections like ABPA, eosinophilia (high eosinophils) is driven by an allergic reaction to fungal antigens colonizing the airways, again involving a Th2 response and IL-5 production.

Common Examples

- Helminthic Infections (Intestinal Worms): Infections like ascariasis, hookworm, strongyloidiasis, and whipworm are relatively common in tropical regions due to environmental factors and sanitation practices. These are often a significant cause of eosinophilia (high eosinophils).

- Tissue-Invading Helminths: Examples include schistosomiasis, cysticercosis (caused by the pork tapeworm), and echinococcosis.

- Protozoan Infections (Less Common for Marked Eosinophilia): While some protozoan infections can cause mild eosinophilia, they are less likely to be the primary cause of high eosinophil counts.

- Fungal Infections: Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis (ABPA), a hypersensitivity reaction to Aspergillus in the airways, is characterized by eosinophilia (high eosinophils).

- Certain Viral Infections: While less common as a primary cause of significant eosinophilia (high eosinophils), some viral infections during the recovery phase can show a transient increase in eosinophils.

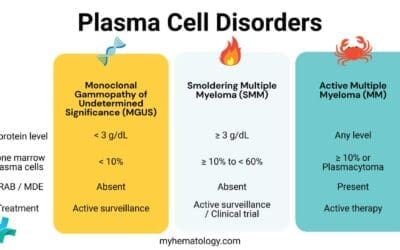

Hematologic Disorders

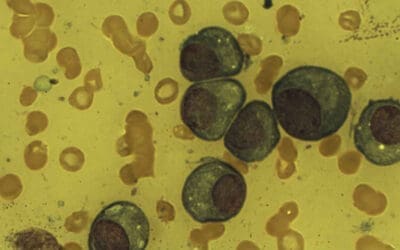

These conditions involve the bone marrow and can lead to the overproduction of eosinophils as part of a broader hematologic abnormality.

Common Examples

- Hypereosinophilic Syndromes (HES): A heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by persistently elevated eosinophil counts (typically >1500/µL) for at least 6 months. HES can be primary (clonal) or secondary (reactive) or idiopathic. The persistently high eosinophil counts in HES can lead to infiltration and damage in various organs, including the heart (eosinophilic myocarditis), lungs (eosinophilic pneumonia), skin, nervous system, and gastrointestinal tract. Symptoms vary depending on the organs involved.

- Chronic Eosinophilic Leukemia, Not Otherwise Specified (CEL-NOS): CEL-NOS is a rare myeloproliferative neoplasm characterized by a sustained increase in peripheral blood eosinophils (absolute eosinophil count ≥ 1.5 x 10⁹/L) and bone marrow eosinophilia (high eosinophils), without the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion gene or other specific genetic abnormalities associated with other myeloid neoplasms. Similar to HES, the elevated eosinophil counts can lead to organ infiltration and damage, with a risk of transformation to acute myeloid leukemia in some patients.

- Myeloid Neoplasms with Eosinophilia and Rearrangement of PDGFRA, PDGFRB, or FGFR1: These are specific subtypes of myeloid neoplasms characterized by eosinophilia (high eosinophils) and specific chromosomal translocations or gene rearrangements involving the platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA), platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta (PDGFRB), or fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) genes. These specific genetic abnormalities are important for diagnosis and often predict responsiveness to specific tyrosine kinase inhibitors like imatinib.

- Hodgkin Lymphoma: Hodgkin lymphoma is a type of lymphoma characterized by the presence of Reed-Sternberg cells. Eosinophilia is frequently observed in Hodgkin lymphoma, although the exact mechanism is not fully understood. It is thought to be a reactive phenomenon, where cytokines (e.g., IL-5) and other factors released by the Reed-Sternberg cells or the surrounding immune cells in the tumor microenvironment stimulate the production and recruitment of eosinophils. The presence and degree of eosinophilia (high eosinophils) in Hodgkin lymphoma can sometimes correlate with disease stage and prognosis.

- Systemic Mastocytosis with an Associated Clonal Hematologic Non-Mast Cell Lineage Disease (SM-AHNMD): Systemic mastocytosis is characterized by the abnormal accumulation of mast cells in various organs. It can be associated with other hematologic neoplasms, including those with eosinophilia (high eosinophils). The presence of eosinophilia (high eosinophils) in systemic mastocytosis can contribute to the overall clinical picture and may require specific management strategies.

Organ-Specific Eosinophilic Diseases

In these conditions, eosinophils infiltrate specific organs, leading to inflammation and tissue damage. The cause is often not fully understood but may involve a combination of genetic predisposition and environmental triggers.

Common Examples

- Eosinophilic Esophagitis (EoE): Characterized by a high density of eosinophils in the esophageal lining, leading to difficulty swallowing, food impaction, and other esophageal symptoms. The exact etiology is not fully understood but is believed to involve a hypersensitivity reaction to food antigens (and sometimes aeroallergens) in genetically predisposed individuals. Diagnosis relies on endoscopic findings (e.g., esophageal rings, furrows, strictures) and esophageal biopsies showing the characteristic high eosinophil count. Treatment focuses on dietary elimination, topical corticosteroids, and sometimes proton pump inhibitors or esophageal dilation.

- Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis (EoG): EoG is a rare disorder characterized by eosinophilic infiltration of one or more segments of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (esophagus, stomach, small intestine, colon) in the absence of known secondary causes of eosinophilia. Similar to EoE, EoG is thought to be triggered by allergic reactions to food antigens, leading to a Th2-mediated immune response and IL-5 production, resulting in eosinophil recruitment to the GI mucosa. Diagnosis involves endoscopic and/or surgical biopsies of the affected GI segments showing increased eosinophil counts. Treatment often includes dietary elimination, corticosteroids, and sometimes other immunomodulatory agents.

- Eosinophilic Asthma: A subtype of severe asthma characterized by prominent eosinophilic inflammation in the airways, often associated with higher sputum and blood eosinophil counts. In these patients, the allergic (or sometimes non-allergic) triggers lead to a persistent Th2-dominated inflammatory response in the lungs, with significant IL-5 production driving eosinophil recruitment and activation in the airways. Identifying eosinophilic asthma is important as these patients may benefit from targeted therapies like anti-IL-5 biologics (e.g., mepolizumab, reslizumab) that reduce eosinophil levels and improve asthma control.

- Eosinophilic Myocarditis: Inflammation of the heart muscle due to eosinophil infiltration, which can lead to heart failure, arrhythmias, and even sudden death. The causes can include hypersensitivity reactions (drugs, vaccines), parasitic infections, hypereosinophilic syndromes, and idiopathic forms. IL-5 plays a role in eosinophil recruitment to the myocardium. Diagnosis often involves elevated cardiac enzymes, ECG changes, echocardiographic abnormalities, and cardiac MRI. Endomyocardial biopsy is the gold standard for confirming eosinophilic infiltration. Treatment includes corticosteroids and management of heart failure.

- Eosinophilic Pneumonia: Eosinophilic infiltration of the lung tissue, causing respiratory symptoms. The causes vary and can include drug reactions, parasitic infections, fungal infections (e.g., ABPA, Churg-Strauss syndrome which has a pulmonary component), and idiopathic forms. Regardless of the trigger, the hallmark is the infiltration of eosinophils into the lung tissue. Diagnosis involves clinical presentation, characteristic findings on chest imaging, and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) or lung biopsy showing increased eosinophil counts. Treatment depends on the underlying cause and may involve corticosteroids.

- Eosinophilic Dermatoses: Various skin conditions, such as bullous pemphigoid and eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells syndrome), involve significant eosinophil accumulation in the skin. The triggers and exact mechanisms vary depending on the specific dermatosis but involve immune dysregulation and the recruitment of eosinophils to the skin. Diagnosis is based on clinical presentation and skin biopsy showing eosinophilic infiltration. Treatment depends on the specific condition and may involve topical or systemic corticosteroids.

Other Causes

- Connective Tissue Diseases: Certain autoimmune disorders like Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (EGPA, formerly Churg-Strauss syndrome) are characterized by eosinophilia, vasculitis, and asthma.

- Endocrine Disorders: Addison’s disease (adrenal insufficiency) can sometimes be associated with mild eosinophilia.

- Malignancies (Non-Hematologic): Some solid tumors can release factors that stimulate eosinophil production.

- Immunodeficiency Syndromes: Certain primary immunodeficiencies can present with eosinophilia.

Idiopathic Eosinophilia

In some cases, despite thorough investigation, no underlying cause for the eosinophilia can be identified. This is termed idiopathic eosinophilia. Some of these cases may eventually evolve into a recognized eosinophilic disorder.

Symptoms of Eosinophilia

The clinical presentation of eosinophilia can range from being completely asymptomatic, especially in mild cases, to causing significant morbidity depending on the underlying etiology and the extent of organ involvement. Symptoms can be broadly categorized as general, systemic, and organ-specific.

General Symptoms (Often Non-Specific)

These symptoms can occur in various conditions associated with eosinophilia and are not specific to eosinophil involvement alone.

- Fatigue: Feeling unusually tired or lacking energy.

- Malaise: A general feeling of discomfort, illness, or unease.

- Myalgia: Muscle aches and pains.

- Arthralgia: Joint pain.

- Weight loss: Unintentional decrease in body weight.

- Fever: Elevated body temperature, although this is more common in infectious or systemic inflammatory causes of eosinophilia.

- Night sweats: Episodes of heavy sweating during sleep.

Systemic Symptoms (Indicating More Widespread Involvement)

These symptoms suggest that the underlying cause of eosinophilia may be affecting multiple body systems or is a more systemic process. They can overlap with general symptoms but often point towards a more significant underlying condition.

- Lymphadenopathy: Swollen lymph nodes, which can occur in hematologic disorders, infections, or some allergic reactions.

- Splenomegaly or Hepatomegaly: Enlargement of the spleen or liver, which can be seen in hypereosinophilic syndrome, hematologic malignancies, or certain infections.

- Skin rashes: Various types of skin eruptions (e.g., urticaria, eczema-like rashes, nodules) can be associated with allergic reactions, drug hypersensitivity, or eosinophilic dermatoses.

- Angioedema: Swelling of the deeper layers of the skin, often involving the face, lips, tongue, or throat, typically seen in allergic reactions.

Organ-Specific Symptoms (Related to Eosinophil Infiltration of Specific Organs)

These symptoms directly reflect the involvement and inflammation of particular organs due to eosinophil infiltration. Recognizing these patterns is crucial for suspecting specific underlying conditions.

Respiratory System

- Cough: Can be dry or productive, especially in eosinophilic asthma or eosinophilic pneumonia.

- Wheezing: A whistling sound during breathing, common in asthma and some allergic reactions affecting the airways.

- Shortness of breath (dyspnea): Feeling breathless or having difficulty breathing, seen in asthma, eosinophilic pneumonia, or eosinophilic myocarditis with heart failure.

- Chest pain or tightness: May occur in eosinophilic asthma or eosinophilic myocarditis.

- Hemoptysis: Coughing up blood, a less common but potentially serious symptom in some lung conditions.

Gastrointestinal System

- Dysphagia: Difficulty swallowing, a hallmark of eosinophilic esophagitis.

- Food impaction: Feeling food stuck in the esophagus, also common in EoE.

- Abdominal pain: Can be localized or diffuse, seen in eosinophilic gastroenteritis.

- Nausea and vomiting: May occur in EoG or with systemic involvement.

- Diarrhea: Can be a symptom of EoG, particularly with small intestinal or colonic involvement.

- Weight loss and malnutrition: In severe or chronic GI involvement.

- Heartburn or reflux-like symptoms: Can occur in EoE.

Cardiovascular System

- Chest pain: May be anginal in nature in eosinophilic myocarditis.

- Palpitations: Awareness of rapid or irregular heartbeats.

- Shortness of breath on exertion: A sign of heart failure in eosinophilic myocarditis.

- Swelling in the legs or ankles (edema): Another sign of heart failure.

- Fatigue: Due to reduced cardiac output.

Skin

- Pruritus (itching): A common symptom in allergic reactions and eosinophilic dermatoses.

- Rashes: Various types depending on the underlying condition (e.g., urticarial, eczematous, bullous).

- Swelling or induration of the skin.

Nervous System (Less Common, but can occur in HES or EGPA)

- Peripheral neuropathy: Numbness, tingling, or weakness in the extremities.

- Central nervous system involvement: Can lead to cognitive changes, seizures, or other neurological deficits in severe cases.

Laboratory Investigations in Eosinophilia

The general laboratory investigations for eosinophilia (high eosinophils) aim to confirm the presence and quantify the degree of eosinophilia (high eosinophils), and then to systematically investigate the underlying cause.

Initial General Assessment

These are the fundamental laboratory tests performed to identify and characterize the eosinophilia itself and to get a baseline understanding of the patient’s overall hematologic status.

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) with Differential: An absolute eosinophil count above the upper limit of normal (typically > 500 cells/µL or 0.5 x 10⁹/L) confirms eosinophilia (high eosinophils). The degree of eosinophilia (mild, moderate, severe) can provide clues about the potential underlying causes.

- Peripheral Blood Smear: Can help identify abnormal eosinophil populations, such as hypogranular or dysplastic eosinophils, which may suggest a hematologic disorder. May indicate a broader hematologic abnormality, such as leukocytosis, anemia, or thrombocytopenia, which could point towards a myeloproliferative neoplasm or other bone marrow disorder. In some cases, circulating microfilariae (larval stages of certain parasitic worms) might be visible on the blood smear, especially if the blood is collected at specific times of the day (nocturnal periodicity).

- Inflammatory Markers: To assess for the presence of systemic inflammation, which can be associated with various causes of eosinophilia, including allergic reactions, infections, and autoimmune diseases.

- Common Tests:

- Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR): A non-specific marker of inflammation.

- C-Reactive Protein (CRP): Another acute-phase reactant that increases in response to inflammation.

- Elevated ESR or CRP can suggest an underlying inflammatory process but do not specifically point to the cause of eosinophilia.

- Common Tests:

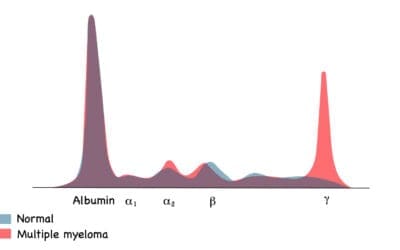

- Serum Immunoglobulin E (IgE) Levels: A high IgE level supports an allergic etiology but is not specific and can also be elevated in certain parasitic infections or hypereosinophilic syndromes. A normal IgE level does not rule out allergic causes.

Determining the Underlying Cause

- Detailed Patient History and Physical Examination

- Stool Examination for Ova and Parasites (O&P): Crucial for suspected parasitic infections. Consider mentioning serial testing.

- Allergy Testing:

- Skin prick tests

- Specific IgE antibody testing (RAST)

- Organ-Specific Investigations:

- Respiratory: Pulmonary function tests, chest X-ray, CT scan, bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and biopsy.

- Gastrointestinal: Endoscopy with biopsies.

- Cardiac: Electrocardiogram (ECG), echocardiogram, cardiac MRI, troponin levels.

- Skin: Skin biopsy.

- Serological Tests: For connective tissue diseases (e.g., ANCA for EGPA).

- Bone Marrow Biopsy: Indicated in cases of persistent, unexplained eosinophilia, suspected hematologic disorders, or hypereosinophilic syndrome.

- Cytogenetic and Molecular Studies: May be necessary in suspected myeloproliferative neoplasms or HES variants.

Treatment and Management of Eosinophilia

The primary goal in managing eosinophilia (high eosinophils) is to identify and treat the underlying cause. Direct treatment of the elevated eosinophil count is often reserved for cases where the cause cannot be readily identified or when the eosinophilia itself is contributing to significant organ damage.

Address the Underlying Cause

This is the cornerstone of eosinophilia (high eosinophils) management. Once the etiology is identified, treatment should be directed at resolving that specific condition.

- Antiparasitic Drugs for Parasitic Infections: Specific medications are chosen based on the identified parasite (e.g., albendazole, mebendazole, ivermectin, praziquantel). Duration and dosage depend on the type and burden of the parasitic infection. Follow-up stool examinations are crucial to confirm eradication.

- Allergen Avoidance and Medications for Allergic Reactions:

- Allergen avoidance: Identifying and minimizing exposure to known allergens (e.g., dust mites, pollen, pet dander, specific foods).

- Antihistamines: To relieve symptoms like itching, sneezing, and runny nose.

- Topical corticosteroids: For localized allergic skin reactions (e.g., eczema).

- Inhaled corticosteroids: The mainstay of long-term asthma management, reducing airway inflammation including eosinophilic inflammation.

- Systemic corticosteroids: Used for more severe allergic reactions or asthma exacerbations.

- Leukotriene modifiers: Can help control asthma symptoms in some patients.

- Epinephrine auto-injector: For anaphylaxis.

- Discontinuation of Offending Drugs: If drug hypersensitivity is suspected, the culprit medication should be stopped immediately. Supportive care may be needed depending on the severity of the reaction.

- Management of Underlying Hematologic Disorders:

- Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES): Treatment varies based on the subtype and organ involvement and can include corticosteroids, interferon-alpha, hydroxyurea, and targeted therapies like imatinib (for FIP1L1-PDGFRA positive cases) or biologic agents (e.g., mepolizumab, reslizumab).

- Chronic Eosinophilic Leukemia (CEL): Treatment may involve tyrosine kinase inhibitors (if specific mutations are present), chemotherapy, or stem cell transplantation in some cases.

- Hodgkin Lymphoma: Treatment involves chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or both, depending on the stage and other prognostic factors. Successful treatment of the lymphoma typically leads to resolution of the reactive eosinophilia (high eosinophils).

- Treatment of Organ-Specific Eosinophilic Diseases:

- Eosinophilic Esophagitis (EoE): Dietary elimination (empiric or allergy-directed), topical corticosteroids (swallowed fluticasone or budesonide), proton pump inhibitors in some cases, and esophageal dilation for strictures. Biologic therapies like dupilumab are also used.

- Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis (EoG): Corticosteroids are often the mainstay of treatment. Dietary modifications or elemental diets may be helpful in some cases. Other immunosuppressants may be considered for refractory disease.

- Eosinophilic Asthma: Inhaled corticosteroids are the foundation. Biologic therapies targeting IL-5 (mepolizumab, reslizumab) or the IL-4/IL-13 pathway (dupilumab) are effective for severe eosinophilic asthma.

- Eosinophilic Pneumonia: Corticosteroids are typically the first-line treatment, with a good response usually seen.

- Eosinophilic Myocarditis: Corticosteroids are often used to reduce inflammation. In cases associated with hypereosinophilic syndrome, treatment of the underlying hematologic condition is crucial. Supportive care for heart failure may also be necessary.

- Eosinophilic Dermatoses: Treatment depends on the specific condition and may include topical or systemic corticosteroids, antihistamines, and other immunomodulatory agents.

- Management of Connective Tissue Diseases: For conditions like Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (EGPA), treatment involves corticosteroids and other immunosuppressants (e.g., cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, methotrexate). Biologic agents like mepolizumab are also used.

Direct Treatment of Eosinophilia (When the Cause is Not Easily Treatable or in Severe Cases)

In situations where the underlying cause cannot be quickly resolved or when the eosinophilia (high eosinophils) is causing significant organ damage, direct reduction of the eosinophil count may be necessary.

- Corticosteroids: Systemic corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone) are highly effective at reducing eosinophil production and promoting their apoptosis (programmed cell death). They are often used as first-line therapy for many eosinophilic disorders, including HES, eosinophilic pneumonia, and severe organ-specific eosinophilic diseases. However, long-term use can have significant side effects, so the goal is often to use the lowest effective dose for the shortest duration possible.

- Biologic Therapies:

- Anti-IL-5 Antibodies (Mepolizumab, Reslizumab): These monoclonal antibodies specifically target IL-5, a key cytokine involved in eosinophil maturation, survival, and recruitment. They are effective in reducing eosinophil counts and improving symptoms in eosinophilic asthma and some subtypes of HES.

- Anti-IL-4/IL-13 Antibody (Dupilumab): While not directly targeting eosinophils, dupilumab can reduce eosinophilic inflammation in conditions like atopic dermatitis and eosinophilic esophagitis by blocking the signaling of IL-4 and IL-13, which are involved in Th2 responses.

- Other Immunosuppressants: Drugs like hydroxyurea, azathioprine, methotrexate, and interferon-alpha may be used in certain chronic eosinophilic conditions, particularly HES, to help control eosinophil counts and reduce organ damage, often as steroid-sparing agents.

- Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (e.g., Imatinib): Specifically used in HES and CEL cases that are positive for the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion gene, as imatinib targets the constitutively active tyrosine kinase produced by this gene.

Monitoring and Follow-up

Regular monitoring is essential to assess treatment response, detect relapses, and monitor for potential complications or side effects of therapy.

- Serial blood eosinophil counts: To track the effectiveness of treatment.

- Monitoring of organ-specific symptoms and function: Through clinical assessments, endoscopy, pulmonary function tests, echocardiography, etc., as appropriate for the affected organs.

- Assessment for side effects of medications: Especially with long-term corticosteroid or immunosuppressant use.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Should I worry about mild eosinophilia?

Mild eosinophilia (typically between 500 and 1500 cells/µL) is a relatively common finding and often doesn’t indicate a serious underlying condition. It can be associated with mild allergic reactions, resolving infections (especially parasitic), or drug reactions, and sometimes it may have no identifiable cause and resolve spontaneously. However, because it can also be an early sign of a more significant issue, such as an evolving allergic disease, a persistent parasitic infection, or a subtle hematologic abnormality.

What medications cause eosinophilia?

Many medications have been associated with causing eosinophilia (high eosinophils) as a side effect. The mechanisms can vary from direct stimulation of eosinophil production to hypersensitivity reactions involving eosinophils. Some of the more commonly implicated drug classes and specific examples include:

- Antibiotics: Penicillins (e.g., amoxicillin, ampicillin), cephalosporins (e.g., cefaclor, ceftriaxone), sulfonamides (e.g., sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, sulfasalazine), nitrofurantoin, minocycline, vancomycin.

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): Aspirin, ibuprofen, naproxen.

- Anticonvulsants: Phenytoin, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, phenobarbital.

- Allopurinol: A medication used to treat gout.

- ACE inhibitors: Captopril, enalapril, lisinopril.

- Ranitidine: An H2 receptor antagonist (though less commonly used now).

- Antidepressants: Tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in rare cases.

- Antiretroviral drugs: Abacavir, nevirapine.

- Diuretics: Thiazide diuretics (e.g., hydrochlorothiazide).

- Other medications: L-tryptophan (especially contaminated supplements), gold salts, certain chemotherapy drugs, and some biologic agents.

Eosinophilia (high eosinophils) is not a common side effect of all these medications, and the likelihood of developing it varies depending on the specific drug, dosage, duration of treatment, and individual patient factors.

Can COVID cause high eosinophils?

While a decrease in eosinophils (eosinopenia) was more commonly observed during the acute phase of COVID-19 infection and was sometimes associated with disease severity, some instances of high eosinophil counts (eosinophilia) have been reported in the context of COVID-19. This eosinophilia can occur during the recovery phase or as a potential late complication, possibly related to immune dysregulation following the viral infection.

Can lack of sleep cause high eosinophils?

Currently, there is no strong scientific evidence to suggest that lack of sleep directly causes a sustained or clinically significant increase in eosinophil counts in otherwise healthy individuals.

What parasites cause high eosinophils?

Many parasites, particularly helminths (worms) that invade tissues, are well-known causes of high eosinophil counts. This is because the migration of larvae through tissues and the presence of the parasite trigger a Th2 immune response, leading to the production and recruitment of eosinophils.

Common Helminth Causes

- Nematodes (Roundworms)

- Ascaris lumbricoides (especially during larval migration through the lungs).

- Strongyloides stercoralis.

- Hookworms (Ancylostoma duodenale, Necator americanus).

- Toxocara canis and Toxocara cati (Visceral Larva Migrans).

- Trichinella spiralis (Trichinosis).

- Filarial worms (Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, Onchocerca volvulus, Loa loa).

- Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Eosinophilic Meningitis).

- Paragonimus spp. (Lung flukes).

- Trematodes (Flukes)

- Schistosoma spp. (Schistosomiasis).

- Fasciola hepatica (Liver fluke).

- Clonorchis sinensis (Chinese liver fluke).

- Opisthorchis spp. (Liver flukes).

- Cestodes (Tapeworms)

- Echinococcus granulosus and Echinococcus multilocularis (Hydatid disease) – eosinophilia is more common if the cyst ruptures or leaks.

- Taenia solium (Cysticercosis) – eosinophilia can occur during larval migration.

Protozoan Causes (Less Common)

Generally, protozoan infections do not cause a significant rise in eosinophils. However, there are some exceptions:

- Cystoisospora belli (formerly Isospora belli).

- Sarcocystis spp. (tissue-dwelling).

- Dientamoeba fragilis (in some cases).

Ectoparasites

Scabies mites (Sarcoptes scabiei) can also be associated with eosinophilia due to the inflammatory reaction in the skin.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Valent P, Degenfeld-Schonburg L, Sadovnik I, Horny HP, Arock M, Simon HU, Reiter A, Bochner BS. Eosinophils and eosinophil-associated disorders: immunological, clinical, and molecular complexity. Semin Immunopathol. 2021 Jun;43(3):423-438. doi: 10.1007/s00281-021-00863-y. Epub 2021 May 30. PMID: 34052871; PMCID: PMC8164832.

- Tao Z, Zhu H, Zhang J, Huang Z, Xiang Z, Hong T. Recent advances of eosinophils and its correlated diseases. Front Public Health. 2022 Jul 25;10:954721. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.954721. PMID: 35958837; PMCID: PMC9357997.

- Kanuru S, Sapra A. Eosinophilia. [Updated 2023 Jun 21]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560929/

- Weaver, M.D.; Glass, B.; Aplanalp, C.; Patel, G.; Mazhil, J.; Wang, I.; Dalia, S. Review of Peripheral Blood Eosinophilia: Workup and Differential Diagnosis. Hemato 2024, 5, 81-108. https://doi.org/10.3390/hemato5010008