TL;DR

Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia also known as Primary ITP is an autoimmune disorder characterized by a low platelet count (thrombocytopenia).

- Causes ▾: The immune system mistakenly attacks and destroys healthy platelets. The exact trigger for this immune response is often unknown.

- Symptoms ▾: Common symptoms of primary immune thrombocytopenia include easy bruising, petechiae (tiny red spots on skin), prolonged bleeding from minor injuries. Severe cases can lead to bleeding from mucous membranes (mouth, nose, gastrointestinal tract).

- Diagnosis ▾: Based on symptoms, physical examination findings, and complete blood count. Additional tests might be needed to rule out other causes of low platelet count.

- Treatment ▾

- Depends on the severity and type of ITP (acute or chronic).

- Corticosteroids are often the first-line treatment for acute ITP.

- Immunoglobulins (IVIG) can be used if corticosteroids are ineffective.

- Thrombopoietin receptor agonists (TPO-RAs) stimulate platelet production and are used in chronic ITP or when other treatments fail.

- Splenectomy (spleen removal) might be considered in severe cases.

*Click ▾ for more information

What is Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia (Primary ITP)?

Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia (Primary ITP) is an acquired autoimmune disorder characterized by an isolated reduction in the platelet count (thrombocytopenia), specifically below 100 x 109/L, in the absence of any other recognizable causes. Platelets are essential blood components responsible for initiating the clotting process and preventing bleeding.

Historically, this condition was known as Idiopathic Thrombocytopenic Purpura (ITP) or, in its long-term form, Chronic Idiopathic Thrombocytopenic Purpura (CITP). However, since the pathophysiology is now known to be immune-mediated, the term Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia is the preferred and most accurate nomenclature used by hematology guidelines today. The “Primary” designation confirms that the ITP is a stand-alone disease, not secondary to another underlying illness.

Classification by Duration: Acute, Persistent, and Chronic ITP

While the underlying disease mechanism is the same (Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia), the condition is clinically classified based on how long it lasts. This distinction is crucial for determining prognosis and management strategies.

| Classification | Duration | Typical Age Group | Key Prognosis |

| Newly Diagnosed ITP | < 3 months | Most common in children | High probability of spontaneous remission. |

| Persistent ITP | 3 to 12 months | All ages | Ongoing disease, but still potential for spontaneous remission. |

| Chronic ITP (The focus of this article) | > 12 months | Most common in adults | Low probability of spontaneous remission, typically requires long-term monitoring and active management. |

Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia vs. Secondary ITP

A fundamental principle in diagnosis is differentiating between primary immune thrombocytopenia and secondary forms of the disease:

- Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia (ITP): Thrombocytopenia is the sole finding, caused by the body’s own immune system mistakenly attacking platelets.

- Secondary ITP: Thrombocytopenia is a manifestation of an identifiable underlying disorder. Causes must be ruled out through laboratory screening, and include infections (HIV, Hepatitis C, H. pylori) and other autoimmune conditions (e.g., Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)).

Pathophysiology of Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia

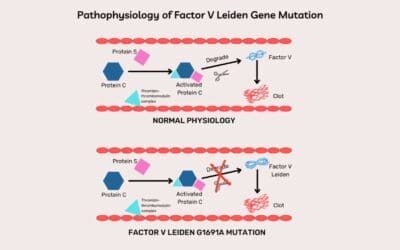

Enhanced Platelet Destruction (The Classic View)

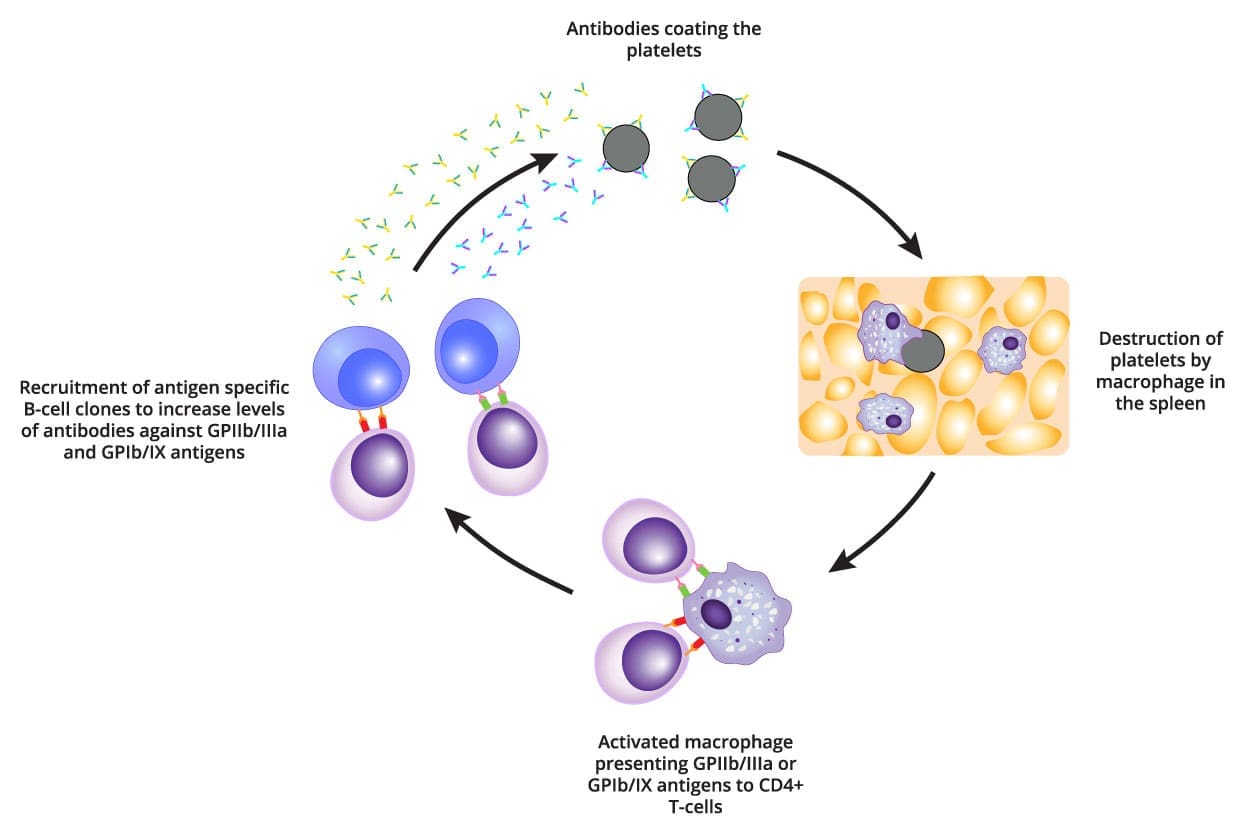

The primary mechanism involves the immune system generating autoantibodies against the patient’s own platelets, marking them for premature clearance.

Immune cells (specifically B-cells) mistakenly produce autoantibodies, predominantly of the IgG class. These antibodies target specific glycoproteins on the platelet surface, with the most frequent targets being:

- Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (GPIIb/IIIa)

- Glycoprotein Ib/IX (GPIb/IX)

Once the antibodies bind to the platelets, the platelets become opsonized (coated). The antibody-coated platelets circulate until they reach the spleen (and to a lesser extent, the liver). Resident macrophages, recognizing the antibody coating as a foreign target, engulf and destroy the platelets via phagocytosis. This process is orchestrated by a T-cell imbalance:

- There is an increase in Th1 and Th17 helper T-cells, which promote the aggressive autoimmune response.

- There is a relative or absolute deficiency in Regulatory T-cells (Tregs), which normally suppress autoimmune activity.

Impaired Platelet Production (The Modern View)

While destruction is rapid, the body’s compensatory production response is often inadequate. The same autoantibodies that target circulating platelets can also bind to and damage megakaryocytes (the platelet-producing cells) in the bone marrow. This binding leads to direct suppression of megakaryocyte maturation and proliferation and increased megakaryocyte apoptosis (programmed cell death).

Although the body attempts to compensate by increasing the size and number of megakaryocytes (often seen on bone marrow biopsy), the net output of platelets is insufficient to match the rapid destruction rate, leading to chronic thrombocytopenia.

Summary of Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Targets

Understanding this dual defect is key to treatment:

| Mechanism | Clinical Effect | Therapeutic Strategy |

| Increased Destruction | Rapid clearance of platelets, short platelet lifespan. | Immunosuppression (Corticosteroids, IVIg, Rituximab) and removal of the primary clearance site (Splenectomy). |

| Impaired Production | Insufficient replenishment of platelets. | Thrombopoietin Receptor Agonists (TPO-RAs) (e.g., Romiplostim, Eltrombopag) to stimulate marrow production. |

Clinical Features of Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia (ITP)

The clinical presentation of Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia (ITP) can range widely, from being completely asymptomatic to presenting as a severe, life-threatening hemorrhagic emergency. Symptoms of Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia are directly related to the degree of thrombocytopenia (low platelet count) and the individual patient’s inherent clotting ability.

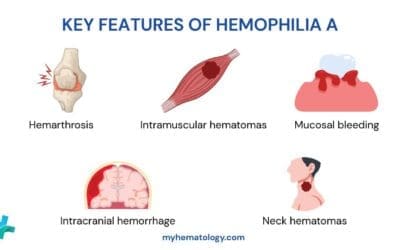

Common Bleeding Manifestations

Bleeding symptoms of Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia (ITP) typically arise when the platelet count drops below 50 x 109/L, and often become significant below 20 x 109/L.

- Petechiae: These are the most characteristic sign. They are pinpoint, reddish-purple spots (1-2 mm) that result from minor capillary bleeding under the skin. They commonly appear on the lower extremities but can occur anywhere, including mucous membranes.

- Purpura: Larger patches of purple skin discoloration caused by bleeding beneath the skin, commonly referred to as easy bruising. This often occurs with minimal or no trauma.

- Mucosal Bleeding: Bleeding from the moist linings of the body, which can be highly indicative of ITP. This includes:

- Epistaxis (nosebleeds).

- Gingival bleeding (bleeding gums), often spontaneous or persistent after brushing.

- Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding (less common, but severe).

- Menorrhagia: Women may experience significantly heavier or prolonged menstrual bleeding (HMB), which can lead to iron deficiency anemia.

Severe and Life-Threatening Bleeding

While rare, the primary concern in severe thrombocytopenia (platelet count <10 x 109/L) is major internal hemorrhage:

- Gastrointestinal (GI) Bleeding: Manifesting as hematemesis (vomiting blood) or melena (dark, tarry stools).

- Intracranial Hemorrhage (ICH): This is the most feared complication and the leading cause of death related to Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia (ITP). Warning signs require immediate emergency intervention and include:

- Sudden, severe, unremitting headache.

- Changes in vision or speech.

- Neurological deficits or altered mental status.

Non-Bleeding Symptoms and Quality of Life (QoL)

Beyond visible bleeding, Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia (ITP) significantly impacts a patient’s daily life, which is a major focus in chronic management.

- Fatigue: Up to 70% of Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia (ITP) patients report significant fatigue, even those with mild thrombocytopenia and no overt anemia. This is believed to be linked to the underlying chronic immune dysregulation and inflammation.

- Emotional Distress: Patients often experience high levels of anxiety and distress related to the unpredictable nature of bleeding episodes and the requirement for continuous monitoring.

Clinical Assessment and Grading

To standardize communication and guide treatment decisions, clinicians often use standardized tools:

- Bleeding Assessment Tools: Systems like the Immune Thrombocytopenia Bleeding Score (IBLS) or the WHO Bleeding Score are utilized to quantify the location and severity of bleeding. Example: Grade 0 (no bleeding) to Grade 4 (disabling or life-threatening bleeding).

This standardized grading helps determine the necessity and urgency of initiating or escalating treatment. For instance, treatment is generally recommended if the platelet count is below 30 x 109/L OR if the patient exhibits clinically significant bleeding, regardless of the platelet count.

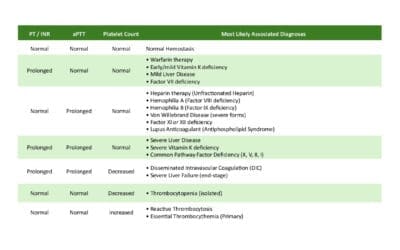

Laboratory Investigations of Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia

The laboratory investigation of Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia (ITP) is not based on finding a single definitive test, but rather on a systematic process to confirm the isolated nature of the thrombocytopenia and exclude all potential secondary causes.

Initial Core Screening

The following tests are mandatory to establish the baseline diagnosis:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): Reveals an isolated low platelet count (thrombocytopenia), typically below 100 x 109/L. All other blood cell lines (white blood cells and red blood cells) should be normal. If other cytopenias are present, the diagnosis shifts away from Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia (ITP).

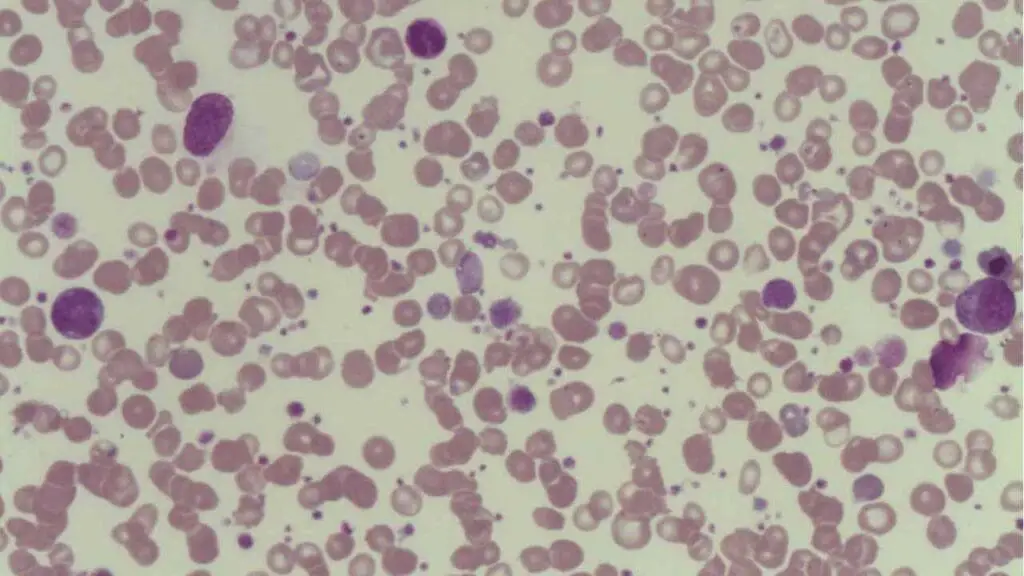

- Peripheral Blood Smear: Confirms thrombocytopenia and often shows the presence of large platelets (megathrombocytes), which are young platelets released prematurely from the stressed bone marrow. The smear must be examined to rule out morphological abnormalities in other cell lines or conditions like Thrombotic Microangiopathy (TMA) or Pseudothrombocytopenia (platelet clumping due to EDTA anticoagulant).

Exclusion of Secondary ITP

Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia (ITP) is a diagnosis of exclusion. A significant portion of the laboratory workup is dedicated to ruling out other diseases that mimic ITP, which would then be classified as Secondary ITP.

| Secondary Cause Category | Required Tests (Knowledge Focus) | Rationale |

| Infections | HIV, Hepatitis C (HCV), H. pylori Testing | These infections can directly or indirectly cause thrombocytopenia. Eradication of H. pylori can cure ITP in some patients. |

| Systemic Autoimmunity | Antinuclear Antibody (ANA), Rheumatoid Factor (RF), Thyroid-stimulating Hormone (TSH) | To screen for underlying connective tissue disorders (e.g., Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)) or autoimmune thyroid disease that may be driving the immune response. |

| Hemolytic Anemia | Direct Antiglobulin Test (DAT) or Coombs Test | A positive DAT suggests that autoantibodies are also targeting red blood cells, pointing toward Evans Syndrome (ITP + Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia). |

Specialized and Confirmatory Tests

These tests are typically reserved for specific clinical scenarios or research, and are not required for the initial diagnosis of Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia in a classic presentation.

- Antiplatelet Antibody Assays: These tests look for specific antibodies (e.g., anti-GPIIb/IIIa) in the patient’s serum or bound to the platelets. While highly specific when positive, they have variable sensitivity. A negative result does not rule out ITP, and a positive result is not required for diagnosis, limiting their routine use.

- Bone Marrow Biopsy (BMB): Typically shows normal or increased numbers of megakaryocytes (due to thrombopoietin stimulation) with normal morphology. BMB is necessary when the diagnosis is uncertain or when another hematological malignancy must be excluded:

- Patients over 60 years old (to rule out Myelodysplastic Syndrome (MDS)).

- Presence of other cytopenias (low hemoglobin or white blood cells).

- Failure to respond to standard first-line treatment.

- Prior to Splenectomy in some centers.

Differential Diagnosis of Thrombocytopenia (Excluding Primary ITP)

| Condition | Mechanism/ITP Type | Key Distinguishing Feature |

| I. Secondary Immune Thrombocytopenia | ||

| Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) | Immune destruction driven by the underlying autoimmune disease. | Positive Antinuclear Antibody (ANA) test; may have other cytopenias (leukopenia, anemia). |

| HIV / HCV Infection | Immune-mediated destruction or direct viral suppression of bone marrow. | Positive viral serology (HIV Ag/Ab or HCV RNA); often associated with other symptoms of infection. |

| Helicobacter pylori Infection | Immune cross-reactivity or stimulation of B-cells. | Positive urea breath test, stool antigen, or serology; often concurrent GI symptoms. |

| Lymphoproliferative Disorders (e.g., CLL) | Often immune-mediated (secondary ITP) or due to bone marrow infiltration. | Abnormal/increased lymphocyte count on CBC; presence of malignant cells on blood smear or flow cytometry. |

| II. Impaired Production / Bone Marrow Failure | ||

| Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS) | Ineffective hematopoiesis in the bone marrow. | Dysplastic (abnormal looking) cells on Peripheral Blood Smear; BMB confirms abnormal marrow morphology. |

| B12 / Folate Deficiency | Impaired DNA synthesis, leading to ineffective hematopoiesis. | Macrocytic anemia (MCV usually high) and sometimes neutropenia; low serum B12/Folate levels. |

| Aplastic Anemia | Destruction of hematopoietic stem cells. | Pancytopenia (low RBCs, WBCs, and platelets); severely hypocellular BMB. |

| III. Increased Consumption / Non-Immune Destruction | ||

| Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura (TTP) | Non-immune consumption of platelets due to microvascular thrombi. | Associated with Microangiopathic Hemolytic Anemia (MAHA) (fragmented RBCs/schistocytes) and often kidney/neurological symptoms. |

| Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC) | Widespread consumption of platelets and clotting factors during systemic activation. | Severe elevation of D-dimer; consumption of clotting factors (prolonged PT/aPTT). |

| IV. Other Causes and Artifacts | ||

| Hypersplenism (e.g., in Cirrhosis) | Splenic sequestration (trapping) of platelets. | Splenomegaly (enlarged spleen) confirmed by imaging; underlying chronic liver disease (abnormal LFTs). |

| Pseudothrombocytopenia | Platelet clumping in vitro (in the test tube) due to EDTA anticoagulant. | Clumped platelets seen on the Peripheral Blood Smear; platelet count normalizes when sample is collected in a different anticoagulant (e.g., citrate). |

| Inherited Thrombocytopenias (e.g., Bernard-Soulier Syndrome) | Genetic defect in platelet structure/function. | Usually chronic from childhood; often very large platelets (giant platelets) on smear; family history. |

Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia (ITP) Treatment & Management

The goal of Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia (ITP) treatment is not to normalize the platelet count, but to prevent clinically significant bleeding, especially severe internal or intracranial hemorrhage. Treatment is generally initiated for patients with a platelet count below 30 x 109/L or any patient experiencing significant bleeding, regardless of the count.

The therapeutic approach is structured into three main lines of defense.

First-Line Therapy (Acute Response)

First-line treatments aim to rapidly suppress the immune-mediated destruction of platelets. They are often used for newly diagnosed patients with significant bleeding or very low platelet counts (<20 x 109/L).

| Therapy | Mechanism of Action | Clinical Notes |

| Corticosteroids | Immunosuppression: Reduce autoantibody production and block Fc receptor function on macrophages, thereby reducing platelet destruction. | Agents: Prednisone (oral) or high-dose Dexamethasone (used as a short, pulsed course). Limitation: Long-term use is restricted due to severe side effects (osteoporosis, weight gain, infection risk). |

| Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIg) | Rapid Blockade: Competitively binds to macrophage Fc receptors, temporarily blocking them from recognizing and destroying antibody-coated platelets. | Used for emergent situations due to its rapid (but temporary, lasting days to weeks) effect. Often used before surgery or delivery. |

| Anti-D Immunoglobulin | RBC Saturation: Causes mild, temporary hemolytic anemia, which saturates macrophage Fc receptors, diverting them from destroying platelets. | Limitation: Only effective in Rh-positive, non-splenectomized patients. Risk of severe hemolysis. |

Second-Line Therapy (Chronic Management)

If Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia (ITP) persists for more than 12 months (becoming Chronic ITP) and patients fail to respond adequately or tolerate first-line therapy, second-line options are considered for long-term management.

Thrombopoietin Receptor Agonists (TPO-RAs)

TPO-RAs are the cornerstone of modern chronic ITP management, addressing the impaired production component of the disease. These drugs mimic the natural hormone thrombopoietin (TPO) by binding to the TPO receptor on megakaryocytes in the bone marrow, stimulating the production of new platelets. Long-term monitoring is required due to the risk of thrombosis (blood clots) and the potential for marrow changes (reticulin fibrosis).

- Agents:

- Romiplostim (Nplate): A weekly subcutaneous injection (peptide-mimetic).

- Eltrombopag (Promacta/Revolade): An oral non-peptide agonist. Must be taken away from divalent cations (calcium, iron, antacids) to ensure proper absorption.

Splenectomy

Surgical removal of the spleen, the primary site of platelet destruction. Generally reserved for chronic ITP that is severe and refractory to medical management. It offers the highest chance of long-term remission but is considered a last resort due to surgical risks.

Patients must receive prophylactic vaccinations against encapsulated organisms (Pneumococcal, Meningococcal, and Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib)) several weeks prior to the procedure, and may require lifelong antibiotic prophylaxis to mitigate the risk of post-splenectomy sepsis.

Immunosuppressive/Immunomodulatory Agents

- Rituximab: A monoclonal antibody that targets CD20 on B-cells, reducing the autoantibody-producing cells.

- Other Agents: Less commonly used second-line drugs include Dapsone, Azathioprine, and Cyclosporine.

Rescue and Refractory ITP Management

Emergency Management

For patients presenting with life-threatening bleeding (e.g., suspected Intracranial Hemorrhage), treatment includes a combination of:

- High-dose IVIg and Corticosteroids.

- Platelet Transfusions: Used sparingly because the transfused platelets will also be rapidly destroyed, but they are essential as a temporary measure in acute, life-threatening hemorrhage.

Refractory ITP

This refers to ITP that persists despite splenectomy and multiple second-line drug treatments. Management often involves continuous TPO-RA use, combination therapy with immunosuppressants, or participation in clinical trials.

Special Populations & Safety Considerations in Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia

Effective management of Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia requires tailored strategies for specific patient groups and a strong focus on long-term safety, particularly concerning splenectomy.

Special Populations: Management Guidance

Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia in Pregnancy

Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia is one of the most common causes of thrombocytopenia during pregnancy (after gestational thrombocytopenia).

- Maternal Management: Treatment decisions are based on the mother’s bleeding risk, not the fetal platelet count. Treatment is usually initiated if the maternal platelet count is <30 x 109/L or if bleeding symptoms are present.

- First-Line: Corticosteroids (e.g., Prednisone) are often preferred.

- Emergency: IVIg is used closer to delivery to rapidly increase the platelet count for hemorrhage risk management.

- Contraindications: TPO-RAs (like Eltrombopag and Romiplostim) and Rituximab are generally avoided, especially in the first trimester, due to insufficient safety data or potential fetal risk.

- Fetal Risk: ITP antibodies rarely cross the placenta in sufficient quantity to cause severe fetal thrombocytopenia. Therefore, routine fetal platelet monitoring is generally not recommended. The mode of delivery is usually determined by standard obstetric indications, with primary immune thrombocytopenia only influencing the decision if the maternal count is severely low.

Pediatric Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia

Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia in children (typically aged 2 to 6 years) has a distinct natural history from adult primary immune thrombocytopenia.

- Prevalence: The majority (~80%) of primary immune thrombocytopenia in children is acute and resolves spontaneously within weeks or months.

- Initial Management: Observation is the standard approach for most children with platelet counts >20 x 109/L and no significant bleeding, as the risk of treatment side effects often outweighs the risk of spontaneous severe bleeding.

- Treatment Threshold: Intervention is usually reserved for children with platelet counts <10 x 109/L or those with significant mucosal bleeding.

- Chronic Form: Approximately 20% of children will develop Chronic ITP (lasting >12 months) and require the long-term management strategies used in adults.

Critical Safety: Post-Splenectomy Management

Splenectomy provides the highest long-term remission rates for refractory ITP, but the loss of the spleen mandates specific, lifelong safety measures due to increased immune vulnerability. The primary risk is a heightened susceptibility to overwhelming sepsis, particularly from encapsulated bacteria (e.g., Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae type B, and Neisseria meningitidis).

Patients must receive the following vaccinations, ideally several weeks prior to the splenectomy to allow for an adequate immune response:

- Pneumococcal Vaccine (PCV13 and PPSV23).

- Meningococcal Vaccine (Serogroups A, C, W, Y and Serogroup B).

- Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib) Vaccine.

Many hematologists recommend placing post-splenectomy patients on long-term (often lifelong) antibiotic prophylaxis (e.g., penicillin or amoxicillin) to protect against life-threatening bacterial infections, especially in the years immediately following the procedure. Patients must be educated about the signs of severe infection and the need to seek immediate medical attention if they develop a fever.

Complications and Prognosis of Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia

Understanding the potential complications and expected long-term outcome (prognosis) is essential for patient counseling and guiding therapeutic decisions in Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia.

Major Complications

The primary risk associated with Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia stems from the low platelet count, but complications can also arise from treatment or chronic disease status.

Hemorrhage (Bleeding Risk)

The most immediate and critical risk is bleeding, which can be categorized by severity:

- Intracranial Hemorrhage (ICH): This is the most feared complication and the leading cause of ITP-related mortality. While rare (occurring in <1% of adult patients), the risk significantly increases when the platelet count is below 10 x 109/L.

- Severe Mucosal Bleeding: Extensive bleeding from the gums, nose, or gastrointestinal tract can lead to acute blood loss and necessitate emergency platelet transfusions.

- Anemia: Chronic or heavy bleeding, particularly menorrhagia (heavy menstrual bleeding) in women, frequently leads to iron deficiency anemia.

Infection Risk (Post-Splenectomy)

As discussed previously, for patients undergoing a splenectomy as part of their Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia management, the loss of the spleen significantly increases the risk of Overwhelming Post-Splenectomy Infection (OPSI), particularly from encapsulated bacteria. This complication is life-threatening and underscores the importance of mandatory pre-operative vaccination.

Treatment-Related Complications

Long-term management carries its own set of risks:

- Corticosteroids: Extended use can lead to weight gain, high blood pressure, diabetes, mood disturbances, and osteoporosis.

- TPO-RAs: Potential for increased risk of thrombosis (blood clots) and dose-dependent marrow changes (reticulin fibrosis).

Prognosis and Remission Rates

The long-term outlook for Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia is largely dictated by the patient’s age and the condition’s duration.

| Patient Group | Form of ITP | Likelihood of Spontaneous Remission | Long-Term Management |

| Children | Newly Diagnosed/Acute ITP (<12 months) | High (~ 80% of cases resolve spontaneously). | Usually observation only. |

| Adults | Chronic Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia (>12 months) | Low (~ 5% per year after 1 year). | Most require long-term monitoring or active treatment with TPO-RAs, corticosteroids, or other agents. |

Overall Outlook

While chronic, ITP is generally a manageable condition. With modern treatments, the majority of patients can maintain platelet counts that minimize the risk of serious bleeding, allowing for a good Quality of Life (QoL).

Mortality

The mortality rate associated with Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia is low, typically related only to the rare occurrence of ICH or complications from treatments like post-splenectomy sepsis. For most patients, Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia is a chronic disease that must be managed, not cured, but it is not typically life-limiting.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the difference between Acute ITP and Chronic ITP?

Acute ITP (most common in children) is sudden in onset and typically resolves on its own within six months. Chronic ITP (most common in adults) lasts for more than 12 months and requires ongoing monitoring and management.

Is Chronic ITP hereditary or contagious?

ITP is not contagious. While most cases are sporadic, there is a slightly increased risk if a close family member has ITP or another autoimmune disorder, suggesting a potential genetic predisposition.

Do I need a bone marrow biopsy for primary immune thrombocytopenia?

In most typical cases of primary immune thrombocytopenia, no. A bone marrow biopsy is generally reserved for patients who do not respond to initial treatment, are over a certain age, or have other unexplained abnormalities in their blood cell counts, to rule out other primary bone marrow disorders.

If I have a low platelet count, what over-the-counter medications should I avoid?

You should avoid any medications that inhibit platelet function or increase bleeding risk. The most common examples are Aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like Ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) and Naproxen (Aleve). Always consult your hematologist before taking any new medication.

What are the long-term side effects of taking TPO-RAs?

Long-term side effects may include an increased risk of thrombosis (blood clots), especially in those with pre-existing risk factors, and the possibility of mild marrow changes such as reticulin fibrosis, which is usually monitored with periodic blood work.

After a splenectomy, what are the lifelong risks?

The primary lifelong risk after a splenectomy is an increased susceptibility to severe infections, particularly from encapsulated bacteria (e.g., S. pneumoniae). This risk is managed by receiving necessary vaccinations prior to the procedure and sometimes requiring antibiotic prophylaxis.

Glossary of Medical Terms

- Autoantibodies: Antibodies produced by the immune system that mistakenly target the body’s own tissues or cells (in this case, platelets).

- Autoimmune Disorder: A condition arising from an abnormal immune response where the body attacks its own healthy cells. Primary ITP is a classic example.

- Chronic ITP: The designation for Immune Thrombocytopenia that persists for longer than 12 months. This is the form most adults progress to.

- Cytopenias: A reduction in the number of any type of mature blood cells (e.g., thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, anemia).

- Epistaxis: The medical term for a nosebleed.

- Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (GPIIb/IIIa): A key receptor protein found on the surface of platelets; it is the most common target of the autoantibodies in ITP.

- Intracranial Hemorrhage (ICH): Bleeding within the skull or brain tissue, which is the most dangerous complication of severe thrombocytopenia.

- Macrophage: A large white blood cell, primarily found in the spleen and liver, that engulfs and destroys damaged cells, foreign particles, or, in ITP, antibody-coated platelets.

- Megakaryocyte: The large bone marrow cell responsible for producing platelets. ITP can impair their function.

- Menorrhagia: Abnormally heavy or prolonged menstrual bleeding.

- Opsonization: The process by which a foreign particle (or in ITP, a platelet) is coated with antibodies, marking it for destruction by phagocytes like macrophages.

- Overwhelming Post-Splenectomy Infection (OPSI): A rare but life-threatening complication of spleen removal, involving rapid and severe infection by encapsulated bacteria.

- Petechiae: Pinpoint, non-blanching red or purple spots on the skin caused by minute hemorrhages, characteristic of low platelet counts.

- Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia: The preferred, modern term for Immune Thrombocytopenia where no underlying cause has been identified.

- Purpura: Larger purple or red areas of bruising caused by bleeding beneath the skin.

- Secondary ITP: Thrombocytopenia that is a direct result of an identifiable underlying disorder, such as HIV, Hepatitis C, or Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE).

- Thrombocytopenia: An isolated condition defined by an abnormally low number of platelets in the blood (count typically $<100 \times 10^9/\text{L}$).

- Thrombopoietin Receptor Agonists (TPO-RAs): A class of medications (e.g., Romiplostim, Eltrombopag) that stimulate megakaryocytes to increase platelet production, thereby treating the production deficit in ITP.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Neunert C, Terrell DR, Arnold DM, et al. American Society of Hematology 2019 guidelines for immune thrombocytopenia. Blood Adv. 2019;3(23):3829-3866.

- Kim DS. Recent advances in treatments of adult immune thrombocytopenia. Blood Res. 2022 Apr 30;57(S1):112-119. doi: 10.5045/br.2022.2022038. PMID: 35483935; PMCID: PMC9057657.

- Gernsheimer T. Chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: mechanisms of pathogenesis. Oncologist. 2009 Jan;14(1):12-21. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0132. Epub 2009 Jan 14. PMID: 19144680.

- Rank A, Weigert O, Ostermann H. Management of chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura: targeting insufficient megakaryopoiesis as a novel therapeutic principle. Biologics. 2010 May 25;4:139-45. doi: 10.2147/btt.s3436. PMID: 20531970; PMCID: PMC2880346.

- Liebman HA, Pullarkat V. Diagnosis and management of immune thrombocytopenia in the era of thrombopoietin mimetics. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2011;2011:384-90. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2011.1.384. PMID: 22160062.

- Goldberg S, Hoffman J. Clinical Hematology Made Ridiculously Simple, 1st Edition: An Incredibly Easy Way to Learn for Medical, Nursing, PA Students, and General Practitioners (MedMaster Medical Books). 2021.