TL;DR

Chediak-Higashi syndrome is a rare, autosomal recessive genetic disorder characterized by defects in lysosomal trafficking.

- Cause: A mutation in the LYST gene.

- Pathophysiology ▾: The

LYSTgene defect leads to the formation of abnormally large, dysfunctional lysosomes in various cells, including immune cells (impairing bacterial killing), melanocytes (causing albinism), and platelets (leading to bleeding issues). - Key Triad ▾: The syndrome is defined by three main features:

- Oculocutaneous albinism (silvery-gray hair and light skin/eyes).

- Recurrent pyogenic infections (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes).

- Progressive neurological abnormalities (e.g., peripheral neuropathy, ataxia).

- Accelerated Phase ▾: A life-threatening complication, clinically identical to hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), triggered by viral infections. It involves an uncontrolled immune response and can be fatal.

- Diagnosis ▾: Primarily by identifying giant cytoplasmic granules in white blood cells on a peripheral blood smear and confirmed by genetic testing for a LYST gene mutation.

- Treatment ▾:

- Symptomatic: Prophylactic antibiotics and immunoglobulin therapy.

- Definitive: The only cure for the immunological and hematological defects is Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT), which should be performed early in life to prevent irreversible neurological damage.

- Prognosis ▾: Without HSCT, the prognosis is poor, with a short life expectancy due to infections or the accelerated phase. With successful HSCT, the prognosis for non-neurological symptoms is significantly improved, but it does not correct the progressive neurological decline.

*Click ▾ for more information

Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS) is a rare, autosomal recessive immunodeficiency disorder characterized by a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations, including hypopigmentation, recurrent pyogenic infections, bleeding diathesis, and neurological abnormalities.

First described in 1943 by Beguez-Cesar, and later in 1952 by Chediak and 1954 by Higashi, this multisystemic disorder results from a defect in intracellular protein trafficking. Understanding the underlying genetic and cellular mechanisms is crucial for early diagnosis and effective management.

Genetic Basis and Pathophysiology

Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS) is caused by a mutation in the LYST gene (also known as CHS1), located on chromosome 1q42-43. The LYST gene encodes for the Lysosomal Trafficking Regulator protein, which is essential for the formation and function of lysosomes and lysosome-related organelles (LROs), such as melanosomes in melanocytes and dense granules in platelets. The LYST protein is a large cytosolic protein that likely plays a role in regulating membrane fusion and fission events within the endosomal-lysosomal pathway.

Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS) has an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern i.e. clinical manifestations are only observed when the mutation is inherited from both parents who are carriers of the disorder.

The defective LYST protein leads to the formation of abnormally large, dysfunctional secretory lysosomes and LROs in various cell types. The hallmark of Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS) is the presence of giant granules, which can be observed in a range of cells, including:

- Leukocytes: Neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes contain oversized lysosomal granules. In neutrophils, these giant granules are unable to fuse with phagosomes, impairing the cell’s ability to destroy engulfed pathogens. This defect in bactericidal activity is the primary cause of the recurrent infections seen in Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS).

- Melanocytes: The melanosomes, which are LROs responsible for producing and storing melanin, are also abnormally large. This leads to impaired melanin transfer to keratinocytes, resulting in the characteristic silvery-white hair and oculocutaneous albinism.

- Platelets: Platelets exhibit a deficiency in dense granules, which are crucial for hemostasis. The lack of these granules impairs platelet aggregation, leading to the bleeding diathesis observed in patients.

- Nerve Cells: The role of LROs in neuronal function is complex, but their dysfunction in Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS) leads to progressive demyelination and neurological deficits.

Clinical Manifestations and Symptoms of Chediak-Higashi Syndrome (CHS)

Chronic Phase

This is the most common presentation in infancy and early childhood. Key features include:

- Immunodeficiency: Recurrent bacterial infections, particularly with Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, and gram-negative bacteria. Infections commonly affect the skin, respiratory tract, and upper airways.

- Oculocutaneous Albinism: A partial, generalized oculocutaneous albinism is a defining feature. This manifests as light skin and hair with a characteristic silvery or greyish sheen. Funduscopic examination may reveal a lack of retinal pigmentation. Photophobia and nystagmus are also common due to the absence of melanin in the iris and retina.

- Bleeding Diathesis: Patients present with easy bruising, epistaxis (nosebleeds), and prolonged bleeding after minor trauma due to defective platelet dense granules, which are essential for proper platelet aggregation and clot formation.

- Neurological Impairment: Progressive neurological decline is a hallmark of Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS). Symptoms typically appear in later childhood or adolescence and include peripheral neuropathy (sensory and motor), ataxia (unsteady gait), intention tremor, and a decline in cognitive function, which can range from mild to severe intellectual disability.

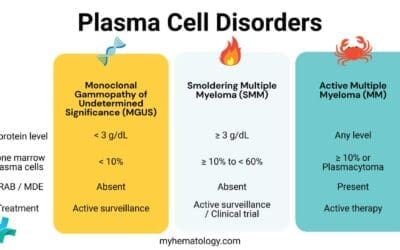

Accelerated Phase (Lymphoproliferative Syndrome)

This is a life-threatening complication that occurs in approximately 85% of patients. It is a severe, systemic lymphohistiocytic infiltration of multiple organs, primarily the liver, spleen, and lymph nodes. It is thought to be a form of reactive hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) triggered by viral infections (most commonly Epstein-Barr virus) or other infectious agents.

- Pathology: This is a life-threatening, acute complication often triggered by viral infections (e.g., Epstein-Barr virus). It involves an uncontrolled, systemic infiltration of activated T-lymphocytes and macrophages into vital organs such as the liver, spleen, bone marrow, and lymph nodes that secrete an abundance of pro-inflammatory cytokines, leading to a cytokine storm.

- Clinical Features: Patients present with fever, hepatosplenomegaly, jaundice, cytopenias (pancytopenia), and coagulopathy.

- Prognosis: Without treatment, the accelerated phase is fatal.

Laboratory Investigations and Diagnosis of Chediak-Higashi Syndrome

The definitive diagnosis of Chediak-Higashi syndrome is established through a combination of characteristic morphological findings and genetic testing.

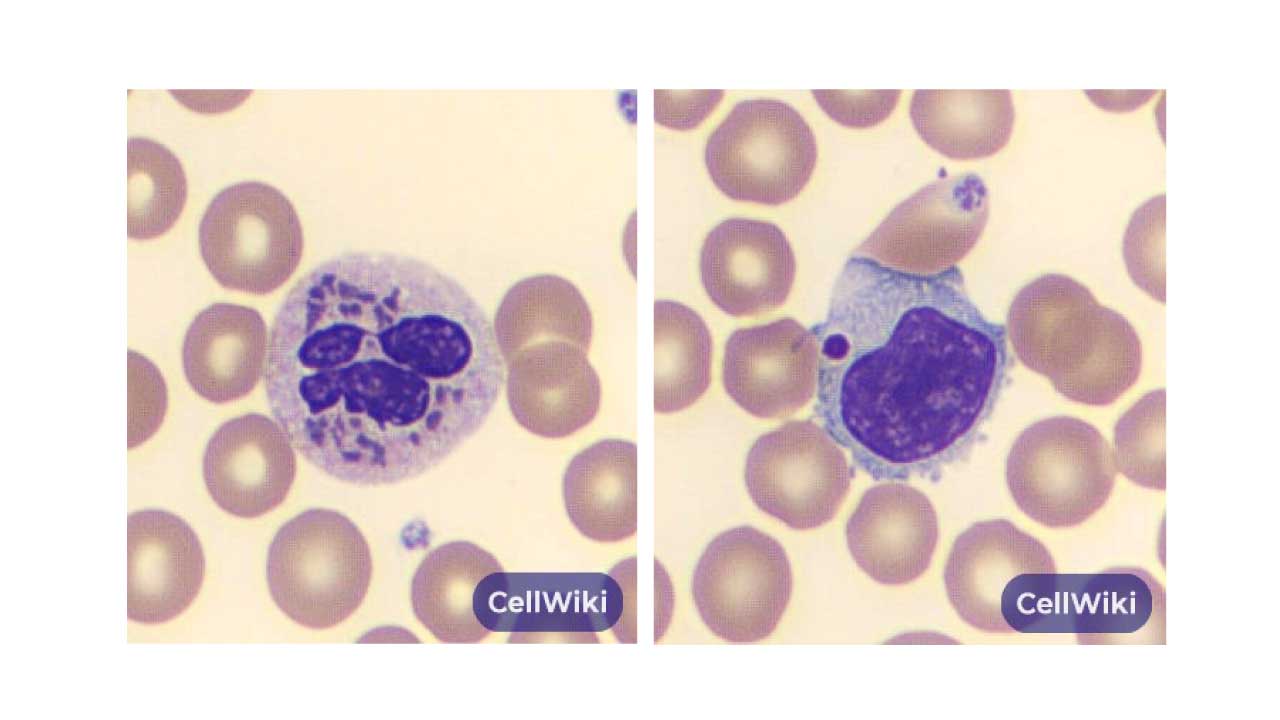

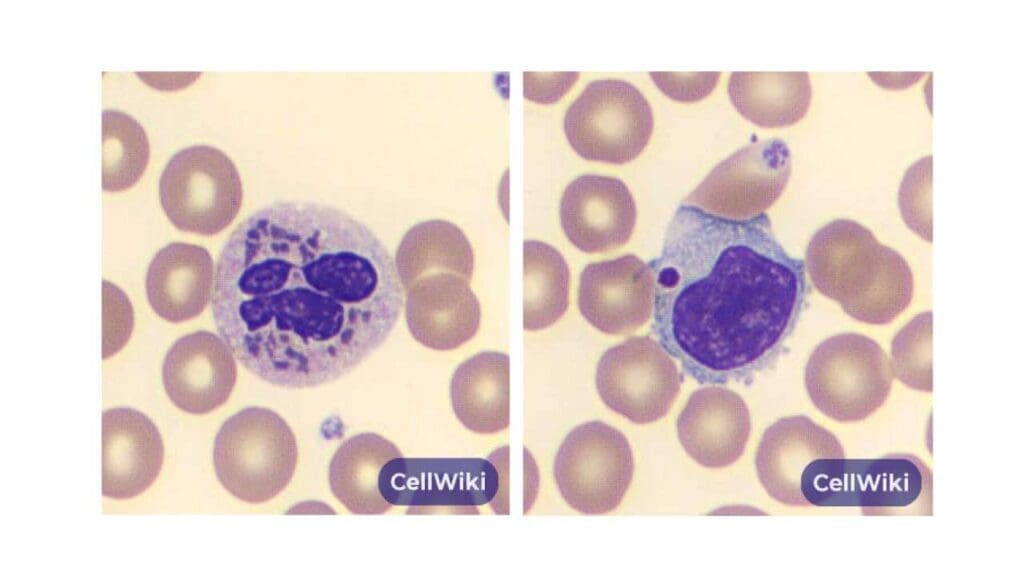

Peripheral Blood Smear

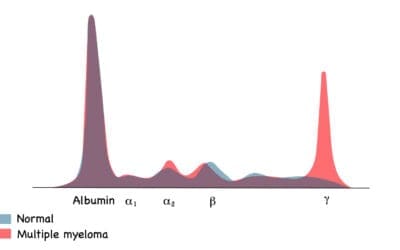

A simple peripheral blood smear will reveal the presence of abnormally large, cytoplasmic granules in various white blood cells. These are particularly prominent in neutrophils, where they appear as large, dark-staining inclusions. Similarly, lymphocytes will also contain large azurophilic granules. The abnormal size of these granules is a direct result of the defective protein trafficking caused by the LYST gene mutation.

Molecular Genetic Testing

While the morphological findings are highly suggestive, genetic testing is the gold standard for confirmation. Molecular analysis is performed to identify a homozygous or compound heterozygous mutation in the LYST gene on chromosome 1q42.1-42.2.

Identifying this specific genetic defect provides a definitive diagnosis and is essential for family counseling and future therapeutic planning, especially for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Flow Cytometry

May show a reduction in NK cell function and abnormal NK cell cytotoxicity.

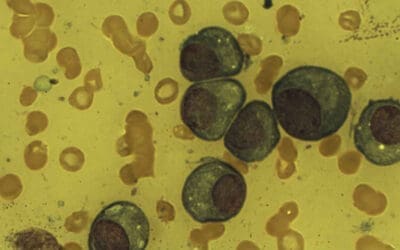

Bone Marrow Aspiration

Myeloid and lymphoid precursor cells in the bone marrow will also contain the characteristic giant inclusions. This finding further supports the diagnosis by demonstrating the defect at the level of cell development.

During the accelerated phase, a bone marrow aspirate often reveals a hallmark finding known as hemophagocytosis. This term describes the engulfment of other blood cells (such as red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets) by histiocytes or macrophages.

In Chediak-Higashi syndrome, this occurs due to the uncontrolled activation of T-lymphocytes and macrophages, which is characteristic of this life-threatening phase. The finding of hemophagocytosis on a bone marrow aspirate is a key diagnostic criterion for the accelerated phase and is essentially a laboratory confirmation of the hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH)-like syndrome.

Differential Diagnosis for Chediak-Higashi Syndrome

| Syndrome | Similarities to CHS | Key Distinguishing Features |

| Griscelli Syndrome (GS) | Oculocutaneous hypopigmentation (silvery-gray hair). GS Type 2 has severe immunodeficiency and a life-threatening “accelerated phase” (HLH-like). | Absence of giant cytoplasmic granules in neutrophils and other leukocytes on peripheral blood smear. Different underlying genetic mutations (RAB27A, MYO5A, MLPH). |

| Hermansky-Pudlak Syndrome (HPS) | Oculocutaneous albinism and a platelet storage pool deficiency leading to bleeding tendencies. | Absence of recurrent pyogenic infections and progressive neurological decline. <br><br> Associated with other specific organ involvements (e.g., granulomatous colitis, pulmonary fibrosis). |

Treatment and Management of Chediak-Higashi Syndrome

Treatment and management for Chediak-Higashi syndrome are divided into two main categories: symptomatic and definitive.

Symptomatic Management

The goal is to manage the life-threatening complications of immunodeficiency and bleeding.

- Antibiotics: Prophylactic antibiotics are crucial to prevent the recurrent, severe pyogenic infections that can lead to significant morbidity and mortality. Patients should be on a daily regimen to protect against common bacterial pathogens like S. aureus.

- Immunoglobulin Replacement Therapy: Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) may be used in some cases to provide passive immunity and support the compromised immune system.

- Bleeding Control: For bleeding episodes, management includes local measures and, if needed, platelet transfusions, though these are often not fully effective due to the platelet function defect.

- Neurological Care: Neurological symptoms are not treatable by the therapies for the other symptoms. Management is supportive, focusing on physical and occupational therapy to maintain function for as long as possible.

Definitive Treatment

The only curative treatment for the immunological and hematological manifestations of Chediak-Higashi syndrome is Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT).

HSCT aims to replace the patient’s defective hematopoietic stem cells with healthy ones from a donor. Success rates are highest when transplantation is performed early in life, before the onset of irreversible neurological damage, as HSCT does not correct the progressive neurological decline. The primary challenge is finding a suitable human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matched donor.

Accelerated Phase Management

This phase is a medical emergency and requires immediate, aggressive immunosuppressive therapy.

Treatment protocols are similar to those for Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), involving a combination of chemotherapy (e.g., etoposide) and corticosteroids to suppress the overwhelming immune response.

Prognosis of Chediak-Higashi Syndrome

The prognosis of Chediak-Higashi Syndrome is highly dependent on whether a patient receives a definitive treatment.

Without a successful hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), the prognosis is generally poor. The majority of patients who do not undergo this treatment often succumb to infections or enter the fatal accelerated phase, with a life expectancy of less than 10 years.

However, with early diagnosis and timely HSCT, the prognosis for the immunological and hematological symptoms is significantly improved. A successful transplant can prevent recurrent infections and bleeding episodes, offering a normal life span. However, HSCT does not correct the progressive neurological decline, so the long-term outlook for neurological function remains guarded, even after a successful transplant.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the life expectancy of a person with Chediak-Higashi syndrome?

Historically, without treatment, life expectancy was short, often not extending beyond the first decade due to recurrent infections and the accelerated phase. With successful hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), the life expectancy has significantly improved, but the long-term prognosis is still affected by progressive neurological decline.

Is Chediak-Higashi syndrome a form of albinism?

It is a type of oculocutaneous albinism (OCA) because it affects both the skin and eyes. However, it is a syndromic form of albinism, meaning the hypopigmentation is part of a larger, multisystemic disorder that includes immunodeficiency and neurological problems, unlike most non-syndromic forms of OCA.

Can parents of a child with Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS) have another child with the same condition?

Since Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS) is an autosomal recessive disorder, if both parents are carriers of the mutated LYST gene, there is a 25% chance with each pregnancy that their child will have Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS), a 50% chance they will be a carrier, and a 25% chance they will be neither a carrier nor affected.

What is the age of onset for Chediak-Higashi syndrome?

For Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS), the age of onset can vary, but symptoms typically begin in early childhood.

- Infancy to Early Childhood: Most children with the classic, more severe form of the disease will show signs and symptoms shortly after birth or by the age of five. This often includes recurrent, severe infections and the characteristic oculocutaneous albinism (silvery-gray hair and light skin/eyes).

- Adolescence/Adulthood: Atypical or milder forms of Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS) can have a later onset, with neurological symptoms becoming the predominant feature in early adulthood, even if the individual has fewer infections.

- Accelerated Phase: The life-threatening accelerated phase can occur at any age but is most common in early childhood and is a significant cause of death in the first decade of life.

What is the difference between HLH and Chediak-Higashi syndrome?

Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS) is the underlying disease, and HLH is a severe, acute, and life-threatening complication that can arise from it.

Patients with Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS) are predisposed to developing HLH because their defective immune cells are unable to properly control viral infections (like Epstein-Barr virus), which can then trigger this hyperinflammatory state. HLH can also be a complication of other conditions, but in the context of Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS), it is a primary concern.

- Chediak-Higashi Syndrome (CHS): This is a rare, inherited genetic disorder. It is the underlying primary disease caused by a mutation in the LYST gene. Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS) is a chronic condition characterized by the triad of immunodeficiency, oculocutaneous albinism, and progressive neurological decline. A person has Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS) from birth.

- Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (HLH): This is not a primary disease but rather a life-threatening, hyperinflammatory syndrome. HLH is a clinical diagnosis defined by a set of signs and symptoms, including fever, splenomegaly, and cytopenias. It is caused by an uncontrolled, systemic over-activation of the immune system, specifically T-lymphocytes and macrophages, which leads to the characteristic finding of hemophagocytosis.

The critical link between the two is that HLH is a potential complication of Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS). In fact, up to 85% of patients with Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS) will develop an “accelerated phase,” which is clinically and pathologically identical to HLH.

What is the triad of Chediak-Higashi syndrome?

The key clinical triad of Chédiak-Higashi syndrome (CHS) is the combination of three primary features:

- Oculocutaneous Albinism: Patients have abnormally light pigmentation of the skin, hair, and eyes, often with a characteristic silvery or greyish sheen to the hair. This is due to a defect in melanin trafficking within melanocytes.

- Recurrent Pyogenic Infections: Due to a profound immunodeficiency, individuals with CHS are highly susceptible to severe and frequent bacterial infections, particularly with Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes.

- Progressive Neurological Abnormalities: As the disease progresses, patients develop a variety of neurological symptoms, including peripheral neuropathy, ataxia (unsteady gait), and intellectual disability.

Glossary of Medical Terms

- Autosomal Recessive: A pattern of inheritance in which an affected individual inherits a mutated gene from each parent.

- Diathesis: A constitutional predisposition or tendency to a particular disease or condition. In this case, a bleeding diathesis is a tendency to bleed.

- Hemophagocytosis: The process by which activated macrophages engulf and destroy other hematopoietic cells, such as red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets.

- Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT): A procedure to replace a person’s hematopoietic stem cells with healthy cells from a donor.

- Lysosomes: Organelles within cells that contain digestive enzymes to break down waste materials, cellular debris, and foreign invaders.

- Oculocutaneous: Relating to or affecting the eyes and skin.

- Pyogenic: Pertaining to the formation of pus.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Ajitkumar A, Yarrarapu SNS, Ramphul K. Chediak-Higashi Syndrome. [Updated 2023 Jul 24]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507881/

- Talbert, M. L., Malicdan, M. C. V., & Introne, W. J. (2023). Chediak-Higashi syndrome. Current opinion in hematology, 30(4), 144–151. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOH.0000000000000766

- Safavi, M., & Parvaneh, N. (2023). Chediak Higashi Syndrome with Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. Fetal and pediatric pathology, 42(2), 259–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/15513815.2022.2077489

- Lozano, M. L., Rivera, J., Sánchez-Guiu, I., & Vicente, V. (2014). Towards the targeted management of Chediak-Higashi syndrome. Orphanet journal of rare diseases, 9, 132. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-014-0132-6

- Helmi, M. M., Saleh, M., Yacop, B., & ElSawy, D. (2017). Chédiak-Higashi syndrome with novel gene mutation. BMJ case reports, 2017, bcr2016216628. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2016-216628

- Ward, D. M., Griffiths, G. M., Stinchcombe, J. C., & Kaplan, J. (2000). Analysis of the lysosomal storage disease Chediak-Higashi syndrome. Traffic (Copenhagen, Denmark), 1(11), 816–822. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.011102.x