TL;DR

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL disease) is a rare and aggressive type of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma that originates from B-cells in the “mantle zone” of the lymph nodes.

- Pathogenesis ▾: The hallmark of MCL is a specific genetic mutation called a chromosomal translocation, t(11;14), which causes an overexpression of the cyclin D1 protein. This protein promotes uncontrolled cell proliferation, leading to the growth of cancerous cells.

- Symptoms ▾: The most common sign is a painless swelling of the lymph nodes in the neck, armpit, or groin. Other “B-symptoms” may include fever, night sweats, and unexplained weight loss.

- Diagnosis ▾: Diagnosis is typically confirmed through a lymph node biopsy. Additional tests, such as a bone marrow biopsy, blood tests (including a WBC count and LDH level), and imaging (like CT or PET scans), are used to stage the disease and determine its extent.

- Treatment ▾: While there is no definitive cure, MCL can be managed with various treatments. The initial approach often involves chemoimmunotherapy. This is often followed by maintenance therapy to prolong remission. For relapsed or refractory disease, newer targeted therapies such as BTK inhibitors and CAR T-cell therapy are used.

*Click ▾ for more information

Introduction

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL disease) is a distinct and relatively rare subtype of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). Recognized for its unique clinical and molecular characteristics, Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL disease) typically accounts for 5-7% of all NHL cases.

Its name is derived from the observation that the malignant cells tend to occupy the mantle zone of lymphoid follicles, though this is not a universal feature. While historically considered an aggressive and incurable lymphoma, recent advances in understanding its biology have led to more targeted and effective treatment strategies, significantly improving patient outcomes.

Pathophysiology and Genetics

The hallmark genetic abnormality in mantle cell lymphoma (MCL disease) is the chromosomal translocation t(11;14)(q13;q32).

This translocation juxtaposes the CCND1 gene on chromosome 11 with the immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGH) gene on chromosome 14. This genomic rearrangement results in the constitutive overexpression of cyclin D1, a key cell cycle regulator that promotes progression from the G1 to the S phase, leading to the hallmark unregulated proliferation of mantle B-cells . Cyclin D1 overexpression is nearly pathognomonic for mantle cell lymphoma (MCL disease) and is a critical diagnostic marker.

While cyclin D1 overexpression is central to the disease, other secondary genetic mutations and molecular pathways contribute to its heterogeneous clinical course. These include mutations in genes such as TP53 and NOTCH1, which are often associated with more aggressive disease variants and poorer prognosis.

The presence of these co-mutations helps explain why some patients have a more indolent clinical course while others present with highly aggressive disease.

Signs and Symptoms of Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL Disease)

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL disease) typically affects older adults, with a median age of diagnosis around 65. The disease often presents with advanced-stage, widespread involvement. The signs and symptoms are often non-specific but can be categorized by the area of the body affected.

Common Symptoms

- Painless Lymphadenopathy: This is the most common sign. Patients will notice enlarged, rubbery, and painless lymph nodes, typically in the neck, armpits, or groin.

- “B Symptoms”: These systemic symptoms are a classic indicator of lymphoma. They include:

- Fever (unexplained and persistent)

- Drenching Night Sweats

- Unexplained Weight Loss (losing more than 10% of body weight over a six-month period)

Other Sites of Involvement

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL disease) often spreads to other organs, leading to additional symptoms.

- Splenomegaly and Hepatomegaly: An enlarged spleen or liver can cause abdominal discomfort, a feeling of fullness after eating only a small amount, and sometimes pain.

- Bone Marrow: When the bone marrow is involved, it can lead to low blood cell counts, causing symptoms like anemia (fatigue, shortness of breath), thrombocytopenia (easy bruising or bleeding), and neutropenia (recurrent infections).

- Gastrointestinal Tract: Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL disease) can affect the digestive system, a condition known as lymphomatous polyposis. This can cause abdominal pain, diarrhea, and weight loss.

Laboratory Investigations and Diagnosis of Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL Disease)

The diagnostic workup for Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL disease) is a multi-step process that combines physical examination with specialized laboratory and imaging studies. The goal is not only to confirm the diagnosis but also to determine the extent of the disease, which is crucial for staging and treatment planning.

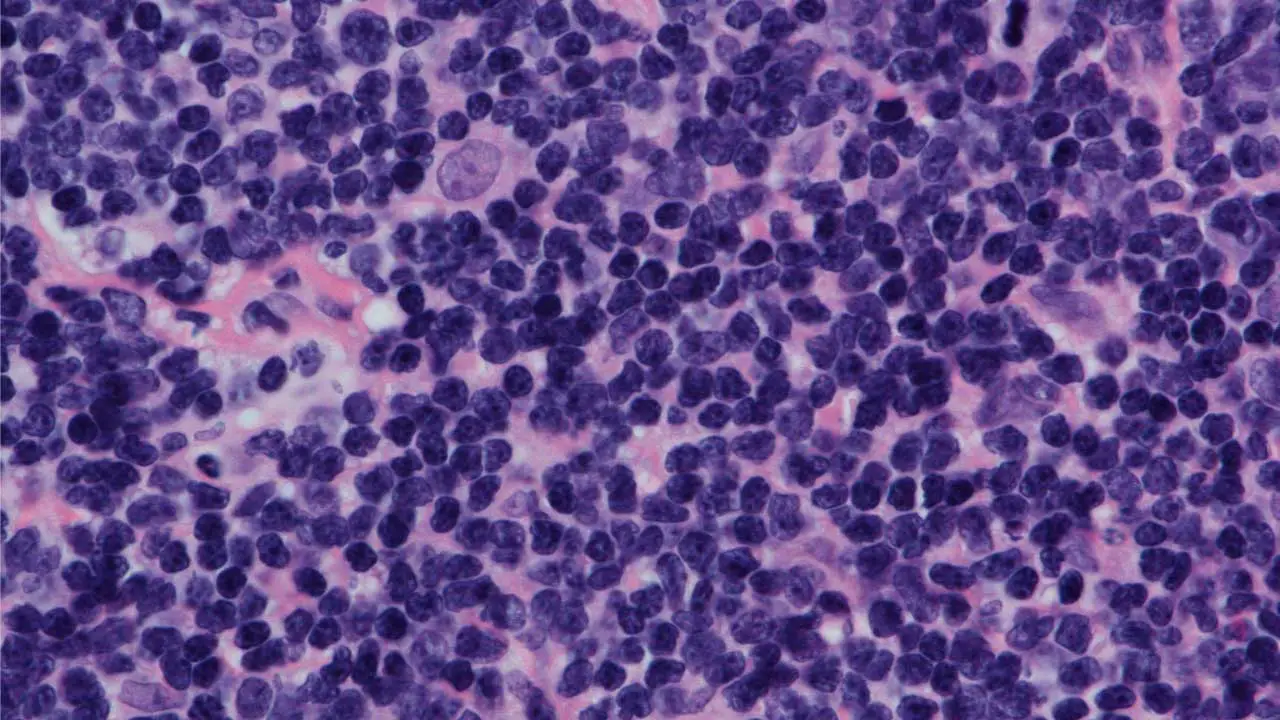

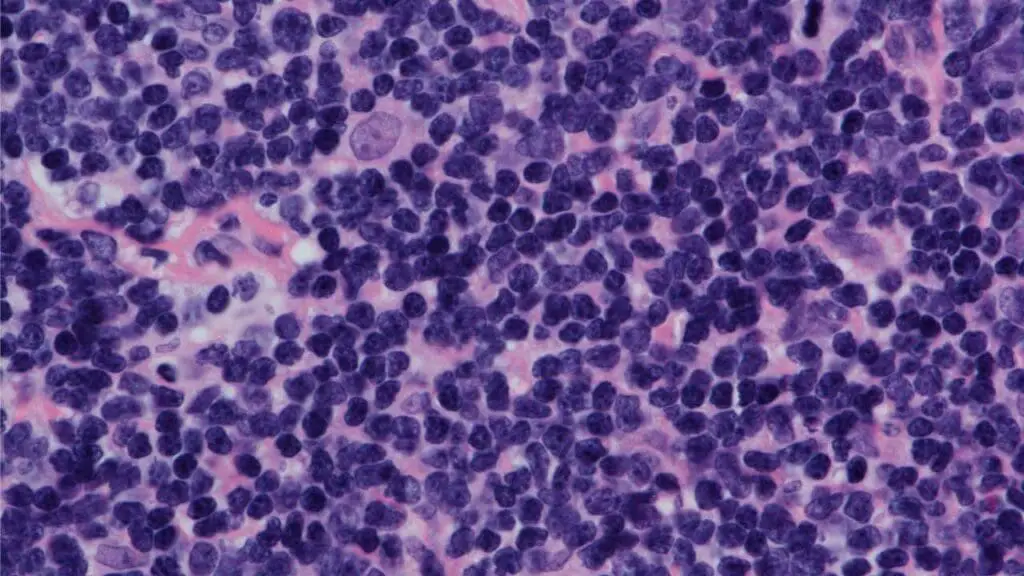

Biopsy

The definitive diagnosis of Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL disease) always requires a biopsy. Typically, an entire enlarged lymph node is surgically removed (excisional biopsy) or a core needle biopsy is taken from an affected area. This tissue is then sent for pathological examination. A small sample may also be sent for cytogenetic analysis.

Laboratory Investigations and Diagnosis

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

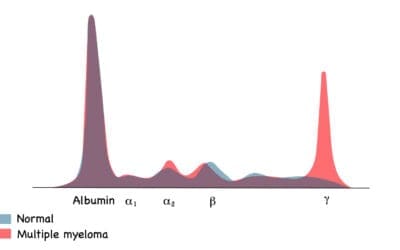

This is the most critical diagnostic tool. Pathologists use antibodies to identify specific proteins expressed by the lymphoma cells. In Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL disease), the characteristic immunophenotype is:

- Positive for B-cell markers such as CD20 and CD5.

- Strongly positive for the overexpression of cyclin D1, which is the direct result of the t(11;14) translocation.

- Negative for CD23 and CD10, which helps to differentiate MCL from other B-cell lymphomas like CLL/SLL and follicular lymphoma.

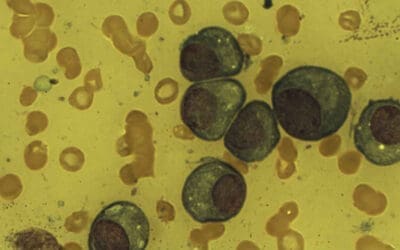

Flow Cytometry

This technique is helpful in Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL disease) to detect abnormal B-cells and confirm the immunophenotype seen on IHC.

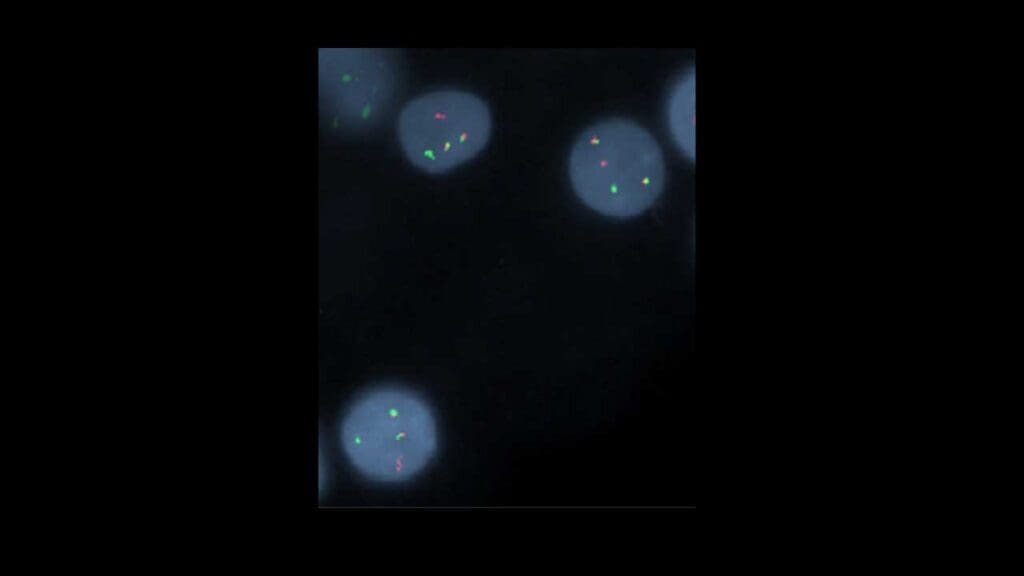

Cytogenetics and FISH

To confirm the genetic hallmark of Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL disease), specific tests are performed:

- Cytogenetics involves analyzing chromosomes to look for the characteristic t(11;14)(q13;q32) translocation.

- FISH (Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization) is a more sensitive molecular test that uses fluorescent probes to light up the specific chromosomes involved in the translocation, providing definitive proof.

Staging and Prognosis

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL disease) is staged using the Ann Arbor staging system, though this system provides limited prognostic information for this disease. The Mantle Cell Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (MIPI) is a more widely used prognostic tool that incorporates clinical factors such as age, ECOG performance status, leukocytosis, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels.

A more recent version, the MIPI-B, also includes the blastoid subtype and Ki-67 proliferative index, which are key indicators of disease aggression. Patients with a high MIPI score have a significantly worse prognosis than those with low or intermediate scores.

Staging tests include:

- CT/PET-CT Scan: This full-body scan is used to identify all sites of disease, including enlarged lymph nodes and involvement of organs like the spleen or liver.

- Bone Marrow Biopsy: Since bone marrow involvement is common in MCL, a bilateral bone marrow biopsy is performed to check for lymphoma cells.

- Peripheral Blood Smear: This simple blood test can show if there are circulating lymphoma cells in the bloodstream.

The Mantle Cell Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (MIPI)

The MIPI is the most widely used and validated clinical prognostic index for Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL disease). It helps to stratify patients into different risk groups based on four key clinical factors. Each factor is assigned a score, and the total score places a patient into a low, intermediate, or high-risk category.

The four clinical factors are:

- Age: Older age is associated with a worse prognosis.

- ECOG Performance Status: This measures a patient’s physical well-being and how well they can perform ordinary tasks. A higher score indicates a poorer functional status and a worse prognosis.

- Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Level: LDH is an enzyme found in most cells. Elevated levels often indicate a high tumor burden and are a poor prognostic factor.

- White Blood Cell (WBC) Count in Complete Blood Count with Differential: A high WBC count can be a sign of widespread disease and is associated with a less favorable outcome.

The Biological MIPI (MIPI-B) and Combined MIPI (MIPI-C)

To enhance the predictive power of the MIPI, a biological component has been integrated. This leads to the MIPI-B, or Biological MIPI, and the MIPI-C, or Combined MIPI, which also includes the Ki-67 proliferation index.

- Ki-67 Proliferation Index: Ki-67 is a nuclear protein that is present during cell proliferation. The Ki-67 index measures the percentage of lymphoma cells that are actively dividing. A high Ki-67 index (typically a cutoff of 30−50%) indicates a more aggressive, fast-growing form of the disease and is a strong predictor of poor prognosis, independent of the clinical MIPI score.

- TP53 Mutation Status: The gene TP53 plays a critical role in regulating the cell cycle and inducing cell death in response to DNA damage. Mutations or deletions in the TP53 gene are found in a significant minority of Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL disease) patients and are a very powerful negative prognostic marker. Patients with TP53-mutated Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL disease) have a poor response to standard chemoimmunotherapy and are considered to have high-risk disease. New treatment strategies, including novel agents and CAR T-cell therapy, are being explored specifically for this subset of patients.

Differential Diagnosis of Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL disease)

The main challenge of differential diagnosis for Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL disease) lies in distinguishing Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL disease) from other B-cell lymphomas that share some of its characteristics, particularly a similar appearance under the microscope or the expression of certain cell surface markers. The key to making the correct diagnosis relies heavily on a combination of immunophenotyping and genetic analysis.

This table summarizes the key features used to differentiate Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL) from other common B-cell lymphomas.

| Feature | Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL) | Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma (SLL) / Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) | Follicular Lymphoma (FL) | Marginal Zone Lymphoma (MZL) |

| Typical Growth Pattern | Diffuse, but can be nodular | Diffuse | Nodular (follicular) | Nodular or diffuse |

| B-Cell Markers | , CD19+ | CD20+ (weak), CD19+ | CD20+, CD19+ | CD20+, CD19+ |

| CD5 Expression | Positive (CD5+) | Positive (CD5+) | Negative (CD5−) | Negative (CD5−) |

| CD10 Expression | Negative (CD10−) | Negative (CD10−) | Positive (CD10+) | Negative (CD10−) |

| CD23 Expression | Negative (CD23−) | Positive (CD23+) | Negative (CD23−) | Negative (CD23−) |

| Cyclin D1 Overexpression | Present (Almost always) | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| SOX11 Expression | Positive (Usually) | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Defining Translocation | t(11;14) | t(13q),trisomy12, etc. | t(14;18) | Varied, e.g., t(11;18) |

Treatment and Management Strategies

The treatment landscape for Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL disease) has evolved from a one-size-fits-all approach to a more nuanced, risk-adapted strategy. The primary goal of treatment is to achieve a deep and durable remission, as Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL disease) is generally considered incurable with standard chemotherapy alone.

The management of Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL disease) is complex and depends on several factors, including the patient’s age, overall health, and the specific subtype of the disease. While Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL disease) is generally considered an aggressive lymphoma, some patients have a more indolent (slow-growing) form that may not require immediate treatment.

Watch and Wait

For a small subset of patients with indolent, asymptomatic Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL disease), a “watch and wait” approach may be appropriate. These patients are typically monitored closely, and treatment is initiated only if symptoms develop or the disease progresses.

Treatment for Younger and Fit Patients

For younger, physically fit patients, the goal is to achieve a deep and durable remission. This typically involves an intensive chemoimmunotherapy regimen followed by a consolidative procedure.

- Initial Chemoimmunotherapy: The most common first-line therapy is a multi-drug regimen, such as Nordic MCL2 or R-CHOP alternating with R-DHAP. These protocols combine the monoclonal antibody Rituximab with several chemotherapy agents to target the lymphoma cells.

- Consolidation: Following the initial therapy, a high-dose chemotherapy regimen with autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) is often used as consolidation. The ASCT helps to replenish the bone marrow with healthy blood-forming stem cells after the high-dose chemotherapy.

Treatment for Older or Less Fit Patients

For older or less fit patients who may not tolerate intensive therapy, the approach is to control the disease and manage symptoms while minimizing toxicity.

- Chemoimmunotherapy: Less aggressive, Rituximab-based regimens are used, such as R-Bendamustine or R-CHOP without the high-dose consolidation. These protocols are effective but have a more manageable side effect profile.

Maintenance and Targeted Therapies

After initial treatment, many patients receive maintenance therapy with Rituximab, which is administered every few months for a period of up to three years. This has been shown to prolong remission duration.

In recent years, several novel, targeted therapies have been approved and are increasingly being used in both the frontline and relapsed settings. These include:

- BTK Inhibitors: Drugs like Ibrutinib, Acalabrutinib, and Zanubrutinib target Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK), a protein that plays a crucial role in B-cell signaling. They have shown great efficacy, particularly in the relapsed setting, and are now being explored in combination with other therapies.

- BCL-2 Inhibitors: Venetoclax targets the BCL-2 protein, which is often overexpressed in Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL disease) cells, allowing them to evade programmed cell death.

- Proteasome Inhibitors: Bortezomib is an example of a proteasome inhibitor that disrupts cell-cycle regulation and can induce cell death in Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL disease).

Relapsed or Refractory Disease

If the disease returns after initial treatment (relapsed) or fails to respond (refractory), a different approach is needed. This often involves a switch to one of the novel targeted therapies mentioned above, or participation in clinical trials exploring new drug combinations and immunotherapies, such as CAR T-cell therapy.

Conclusion

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL disease) remains a challenging disease, but its management has been transformed by a deeper understanding of its molecular pathogenesis and the development of effective targeted therapies.

The combination of chemoimmunotherapy, autologous stem cell transplantation for select patients, and the strategic use of BTK inhibitors has substantially improved outcomes. As research continues to uncover new molecular pathways and therapeutic targets, the future of Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL disease) treatment is moving towards more personalized and less toxic regimens, with the ultimate goal of achieving longer-lasting remissions and, potentially, a cure.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the survival rate for mantle cell lymphoma?

Survival rates for Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL disease) have significantly improved with new treatments. The five-year relative survival rate is approximately 50-60%, though some sources state it can be as high as 65%. The median overall survival, which is the point at which half of patients are still alive, is generally between 5 to 7 years, but this can be much longer for younger patients who respond well to aggressive therapy.

What is Stage 4 mantle lymphoma?

Stage 4 mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is the most advanced stage of the disease. It means the cancer has spread widely, or is “disseminated,” throughout the body.

Can mantle cell lymphoma spread to the brain?

Yes, mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) can, in rare cases, spread to the brain and spinal cord, which is known as central nervous system (CNS) involvement. This is considered a serious complication and can occur either at the time of initial diagnosis or, more commonly, as a relapse of the disease.

When MCL affects the central nervous system, it can lead to various neurological symptoms such as headaches, dizziness, confusion, seizures, or other signs depending on the location of the tumor. Because this is a rare but significant event, specific treatment strategies are used to target the CNS. Factors that increase the risk of CNS involvement often include high-risk features of the disease, like a high Ki-67 proliferation index or a blastoid variant.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Dreyling, M., Campo, E., Hermine, O., Jerkeman, M., Le Gouill, S., Rule, S., Shpilberg, O., Walewski, J., Ladetto, M., & ESMO Guidelines Committee (2017). Newly diagnosed and relapsed mantle cell lymphoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology, 28(suppl_4), iv62–iv71. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx223

- Lynch DT, Koya S, Dogga S, et al. Mantle Cell Lymphoma. [Updated 2023 Jul 28]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536985/

- Wang, Y., & Ma, S. (2014). Risk factors for etiology and prognosis of mantle cell lymphoma. Expert review of hematology, 7(2), 233–243. https://doi.org/10.1586/17474086.2014.889561

- Ryan, C. E., Armand, P., & LaCasce, A. S. (2025). Frontline management of mantle cell lymphoma. Blood, 145(7), 663–672. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2023022352

- Silkenstedt, E., & Dreyling, M. (2023). Mantle cell lymphoma-Update on molecular biology, prognostication and treatment approaches. Hematological oncology, 41 Suppl 1, 36–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/hon.3149

- Navarro, A., Beà, S., Jares, P., & Campo, E. (2020). Molecular Pathogenesis of Mantle Cell Lymphoma. Hematology/oncology clinics of North America, 34(5), 795–807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hoc.2020.05.002

- Kumar, A., Eyre, T. A., Lewis, K. L., Thompson, M. C., & Cheah, C. Y. (2022). New Directions for Mantle Cell Lymphoma in 2022. American Society of Clinical Oncology educational book. American Society of Clinical Oncology. Annual Meeting, 42, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1200/EDBK_349509

- Gerson, J. N., & Barta, S. K. (2019). Mantle Cell Lymphoma: Which Patients Should We Transplant?. Current hematologic malignancy reports, 14(4), 239–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11899-019-00520-0

- Ye, H., Desai, A., Zeng, D., Nomie, K., Romaguera, J., Ahmed, M., & Wang, M. L. (2017). Smoldering mantle cell lymphoma. Journal of experimental & clinical cancer research : CR, 36(1), 185. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-017-0652-8

- Ibrahim FA, Omri HE, Taha RY, Hijji IA, ElKhalifa M, Sabbagh AA. Mantle Cell Lymphoma: A Report of a Case with a Blend of Atypical Features. Indian Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2013;4. doi:10.4137/IJCM.S10608