TL;DR

AL amyloidosis is a systemic disease caused by a clonal plasma cell disorder, leading to the production and deposition of abnormal light-chain amyloid fibrils in organs and tissues.

- Pathophysiology ▾: Abnormal plasma cells overproduce light chains that misfold, aggregate into amyloid fibrils, and deposit in organs, causing damage.

- Causes/Risk Factors ▾: Primarily a clonal plasma cell dyscrasia, with age being the major risk factor. MGUS and multiple myeloma can increase risk.

- Symptoms ▾: Variable, including fatigue, weight loss, and organ-specific symptoms like heart failure, kidney problems, neuropathy, and gastrointestinal issues. Cardiac involvement is especially critical.

- Investigations ▾: Serum free light chain assay, SPEP/UPEP, bone marrow biopsy, tissue biopsy with Congo red staining and mass spectrometry, and cardiac biomarkers are crucial for diagnosis.

- Treatment ▾: Focuses on suppressing plasma cell activity with chemotherapy (bortezomib-based, daratumumab-based regimens, or in select cases, ASCT), and managing organ dysfunction with supportive care.

- Prognosis ▾: Varies based on organ involvement, especially cardiac, and response to treatment. Early diagnosis and treatment are critical for improved outcomes.

*Click ▾ for more information

Introduction

Amyloidosis is a group of rare diseases where an abnormal protein, called amyloid, builds up in tissues and organs throughout the body. This accumulation of amyloid can damage those organs and tissues, leading to a variety of health problems. AL amyloidosis, also known as primary amyloidosis, is a rare and serious disease characterized by the overproduction of abnormal light-chain proteins by a clone of plasma cells in the bone marrow. These abnormal light chains misfold and clump together, forming amyloid fibrils that deposit in various organs and tissues throughout the body, causing damage and dysfunction.

Pathophysiology of AL Amyloidosis

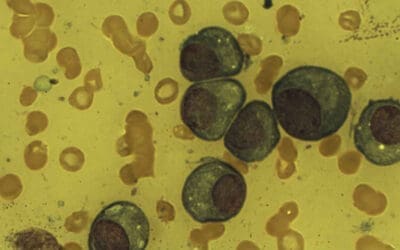

AL amyloidosis originates from a clonal plasma cell disorder within the bone marrow. This means that a single abnormal plasma cell begins to multiply uncontrollably, creating a population of identical cells. These clonal plasma cells produce an excessive amount of monoclonal immunoglobulin light chains.

Immunoglobulins, or antibodies, are composed of heavy and light chains. In AL amyloidosis, the abnormal plasma cells overproduce light chains. These light chains are often structurally unstable, making them prone to misfolding. This means that these light chains don’t fold into their correct three-dimensional shape.

These misfolded light chains then aggregate and assemble into insoluble fibrils known as amyloid fibrils. These fibrils have a characteristic beta-pleated sheet structure, which contributes to their insolubility and resistance to degradation.

The amyloid fibrils deposit in various organs and tissues throughout the body. Commonly affected organs include the heart, kidneys, liver, nerves, and gastrointestinal tract. The accumulation of amyloid deposits disrupts the normal structure and function of these organs.

For example:

- Cardiac amyloidosis: Amyloid deposits in the heart can lead to heart failure, arrhythmias, and conduction abnormalities.

- Renal amyloidosis: Deposits in the kidneys can cause proteinuria, nephrotic syndrome, and renal insufficiency.

- Neuropathy: Deposits in nerves can result in peripheral neuropathy and autonomic dysfunction.

Not all light chains have the same propensity to form amyloid. Some light chains are inherently more unstable and prone to misfolding. The local tissue environment can influence amyloid deposition.

Causes and Risk Factors of AL Amyloidosis

Primary Cause

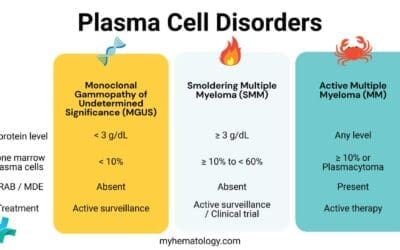

- Clonal Plasma Cell Dyscrasia: AL amyloidosis is fundamentally caused by a disorder of plasma cells in the bone marrow. These abnormal plasma cells produce an excess of monoclonal immunoglobulin light chains, which misfold and form amyloid fibrils. This clonal proliferation is similar to, but often less advanced than, that seen in multiple myeloma.

Risk Factors

- Age: The most significant risk factor is increasing age. AL amyloidosis is more common in older adults, with the median age at diagnosis being in the mid-60s.

- Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance (MGUS): Some individuals with MGUS, a condition characterized by the presence of a monoclonal protein in the blood, may progress to AL amyloidosis. However, the risk of this progression is relatively low.

- Multiple Myeloma: Although less common, AL amyloidosis can occur in conjunction with multiple myeloma. Having multiple myeloma increases the possibility of also developing AL amyloidosis.

- Gender: Men are slightly more likely to develop AL amyloidosis than women.

Clinical Manifestations (Symptoms) of AL Amyloidosis

The signs and symptoms of AL amyloidosis are highly variable and often nonspecific, which can make diagnosis challenging. They depend on which organs are affected by amyloid deposition. The presentation of symptoms can be very subtle in the early stages of the disease. Cardiac involvement is a major predictor of poor prognosis.

General/Systemic Symptoms

- Fatigue: Persistent and unexplained tiredness is a common complaint.

- Weakness: General muscle weakness.

- Weight loss: Unintentional weight loss, often significant.

- Shortness of breath: Especially with exertion.

- Swelling (edema): Particularly in the legs and ankles.

Organ-Specific Symptoms

- Cardiac Involvement (Cardiac Amyloidosis)

- Shortness of breath, especially with exertion (dyspnea).

- Swelling in the legs and abdomen (edema).

- Irregular heartbeat (arrhythmias).

- Lightheadedness or fainting (syncope).

- Chest pain.

- Heart failure.

- Renal Involvement (Renal Amyloidosis)

- Protein in the urine (proteinuria).

- Swelling in the legs and around the eyes (edema).

- Decreased kidney function.

- Neurological Involvement (Neuropathy)

- Numbness, tingling, or pain in the hands and feet (peripheral neuropathy).

- Dizziness or lightheadedness upon standing (orthostatic hypotension).

- Changes in bowel or bladder function (autonomic neuropathy).

- Carpal tunnel syndrome.

- Gastrointestinal Involvement

- Enlarged tongue (macroglossia).

- Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia).

- Nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea.

- Abdominal pain or bloating.

- Gastrointestinal bleeding.

- Liver Involvement

- Enlarged liver (hepatomegaly).

- Abnormal liver function tests.

- Skin and Soft Tissue Involvement

- Skin thickening or bruising (purpura), especially around the eyes.

- “Shoulder pad sign” (thickening of the skin in the shoulder area).

- Easy bruising.

- Other Potential Symptoms

- Hoarseness.

- Joint pain.

Laboratory Investigations

Accurate and timely laboratory investigations are crucial for the diagnosis and management of AL amyloidosis.

Screening Tests

- Serum Free Light Chain (FLC) Assay: This is a highly sensitive and specific test for detecting monoclonal light chains in the blood. It measures the levels of kappa and lambda light chains, and the ratio between them. An abnormal FLC ratio is a strong indicator of a plasma cell dyscrasia.

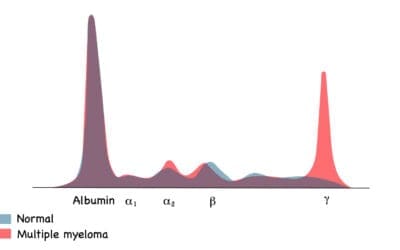

- Serum and Urine Protein Electrophoresis (SPEP/UPEP): These tests identify and quantify abnormal proteins in the serum and urine. They can detect the presence of a monoclonal protein (M-protein), which is often seen in AL amyloidosis.

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): Anemia is a common finding in AL amyloidosis.

- Renal Function Tests: These tests measure kidney function by assessing levels of creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN). They can detect renal impairment, which is a frequent complication of AL amyloidosis.

- Liver Function Tests: These tests evaluate liver function by measuring levels of liver enzymes and bilirubin. They can detect liver involvement, which can occur in AL amyloidosis.

- Cardiac Biomarkers (Troponin, NT-proBNP): These tests measure levels of cardiac proteins that are released when the heart muscle is damaged. Elevated levels can indicate cardiac involvement, which is a critical prognostic factor.

Confirmatory Tests

- Bone Marrow Biopsy and Aspirate: This procedure can identify clonal plasma cells and determine the percentage of plasma cells in the bone marrow.

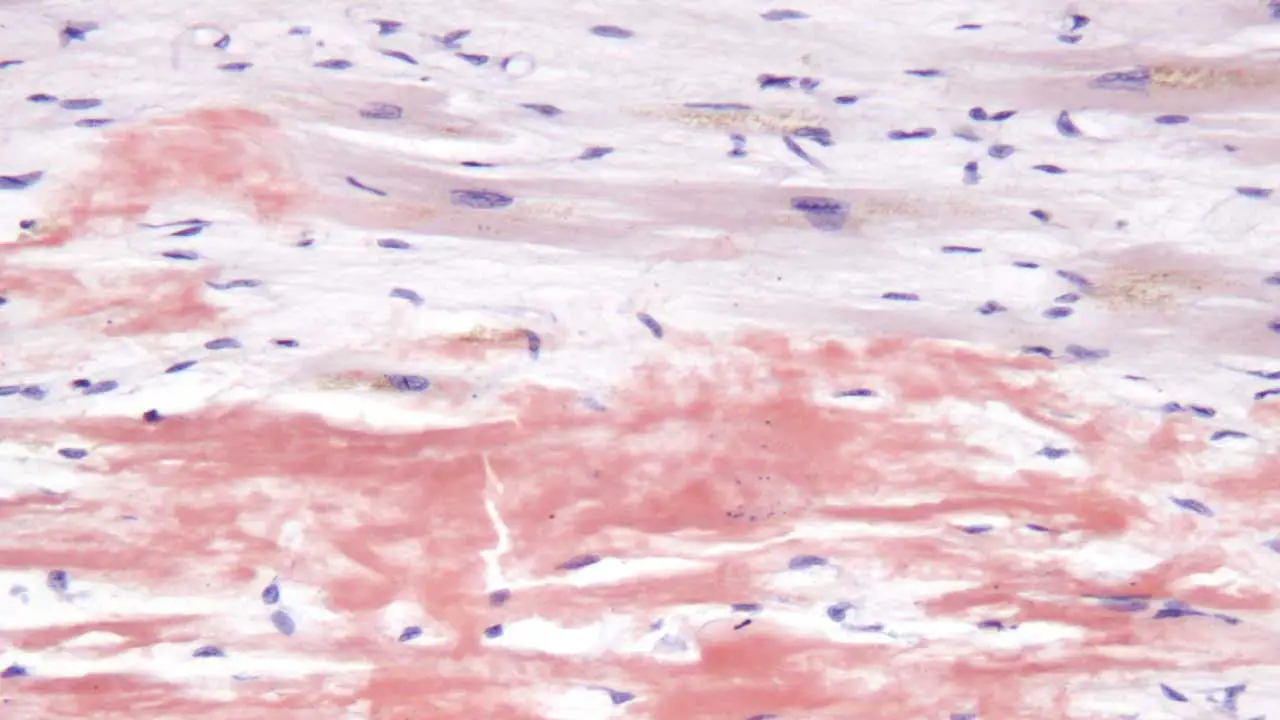

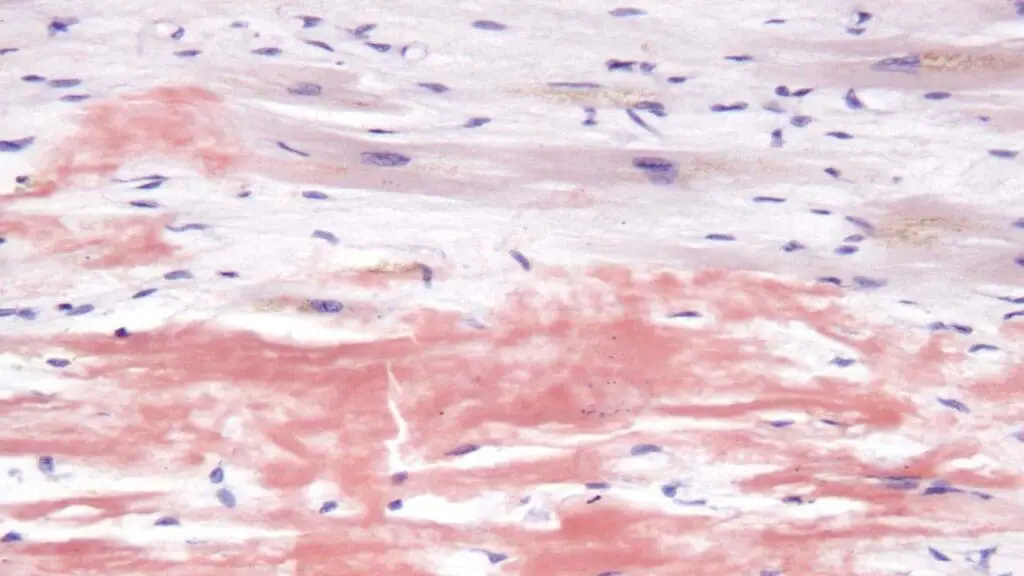

- Tissue Biopsy with Congo Red Staining: This is the gold standard for confirming the presence of amyloid deposits. A sample of tissue (e.g., abdominal fat pad, rectal mucosa, or affected organ) is stained with Congo red dye. Amyloid deposits exhibit characteristic apple-green birefringence under polarized light.

- Mass Spectrometry: This advanced technique identifies the specific type of amyloid protein. It’s essential for distinguishing AL amyloidosis from other types of amyloidosis, such as ATTR amyloidosis.

- Cardiac MRI and Echocardiography: These imaging studies assess cardiac structure and function. They can detect cardiac amyloidosis, which is a major prognostic factor.

Treatment and Management

The treatment and management of AL amyloidosis aim to suppress the production of amyloidogenic light chains, prevent further organ damage, and manage existing organ dysfunction.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the mainstay of treatment for AL amyloidosis. The choice of regimen depends on the patient’s overall health, organ involvement, and risk stratification.

- Bortezomib-based regimens: Bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor, is a cornerstone of AL amyloidosis treatment. It is often combined with other drugs, such as cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone (CyBorD).

- Daratumumab-based regimens: Daratumumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting CD38, has shown significant efficacy in AL amyloidosis. It’s often used in combination with bortezomib and dexamethasone.

- High-dose melphalan and autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT): In carefully selected younger, fit patients with limited cardiac involvement, high-dose melphalan followed by ASCT can be considered. However, due to the high risk of treatment related mortality, this treatment is not used as often as it once was.

Supportive Care

- Cardiac Management

- Diuretics to manage fluid overload.

- Medications to control heart rate and rhythm.

- Pacemaker implantation for conduction abnormalities.

- Renal Management

- Management of proteinuria and edema.

- Dialysis may be required in patients with severe renal failure.

- Neuropathy Management

- Medications for neuropathic pain.

- Physical therapy and occupational therapy.

- Gastrointestinal Management

- Dietary modifications.

- Medications to manage nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

- Nutritional Support: Because of the frequency of GI involvement, and the general effect of the disease, good nutrition is very important.

Monitoring and Follow-Up

Regular monitoring of serum free light chain levels, cardiac biomarkers, and organ function tests is essential to assess treatment response and detect disease progression. Follow-up imaging studies, such as echocardiography and cardiac MRI, may be performed to monitor cardiac involvement.

Prognosis of AL Amyloidosis

The prognosis of AL amyloidosis is highly variable and depends on several factors, primarily the extent of organ involvement, especially cardiac involvement, at the time of diagnosis. Historically, the prognosis of AL amyloidosis was poor, particularly for patients with cardiac involvement. However, advances in treatment, including the development of new chemotherapy regimens, have significantly improved outcomes. Patients who achieve a deep hematologic response have a much better prognosis. The prognosis is highly individualized, and it’s essential to consider each patient’s specific circumstances.

Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial for improving outcomes. Raising awareness of the signs and symptoms of AL amyloidosis can help facilitate early diagnosis.

Key Prognostic Factors

- Cardiac Involvement: Cardiac involvement is the most significant determinant of prognosis. Patients with cardiac amyloidosis have a significantly worse prognosis than those without. Cardiac biomarkers, such as troponin and NT-proBNP, are crucial for assessing cardiac involvement and predicting survival. The degree of cardiac involvement is often staged, and those stages correlate very well with survival.

- Serum Free Light Chain (FLC) Levels: High FLC levels at diagnosis are associated with a poorer prognosis. The difference between the involved and uninvolved light chain (dFLC) is also important. Achieving a deep hematologic response (i.e., a significant reduction in FLC levels) is associated with improved survival.

- Bone Marrow Plasma Cell Percentage: A higher percentage of plasma cells in the bone marrow is associated with a worse prognosis.

- Renal Involvement: While not as significant as cardiac involvement, renal involvement can also impact prognosis.

- Overall Patient Fitness: The patient’s overall health and ability to tolerate treatment are important factors. Those patients who are able to tolerate the current recommended treatments have a much better prognosis.

- Time to Treatment:Early diagnosis and prompt initiation of treatment are crucial for improving outcomes. Delays in diagnosis and treatment can lead to irreversible organ damage.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Al Hamed R, Bazarbachi AH, Bazarbachi A, Malard F, Harousseau JL, Mohty M. Comprehensive Review of AL amyloidosis: some practical recommendations. Blood Cancer J. 2021 May 18;11(5):97. doi: 10.1038/s41408-021-00486-4. PMID: 34006856; PMCID: PMC8130794.

- Fotiou D, Theodorakakou F, Kastritis E. Biomarkers in AL Amyloidosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Oct 9;22(20):10916. doi: 10.3390/ijms222010916. PMID: 34681575; PMCID: PMC8536050.

- Bou Zerdan M, Nasr L, Khalid F, Allam S, Bouferraa Y, Batool S, Tayyeb M, Adroja S, Mammadii M, Anwer F, Raza S, Chaulagain CP. Systemic AL amyloidosis: current approach and future direction. Oncotarget. 2023 Apr 26;14:384-394. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.28415. PMID: 37185672; PMCID: PMC10132994.

- Mansilla Polo M, Llavador-Ros M. AL Amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2024 Aug 15;391(7):640. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm2403455. PMID: 39141856.

- Zhang Y, Comenzo RL. Immunotherapy in AL Amyloidosis. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2022 Jul;23(7):1059-1071. doi: 10.1007/s11864-021-00922-4. Epub 2022 May 30. PMID: 35635625.

- Palladini G, Merlini G. How I treat AL amyloidosis. Blood. 2022 May 12;139(19):2918-2930. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020008737. PMID: 34517412.

- Palladini G, Milani P. Diagnosis and Treatment of AL Amyloidosis. Drugs. 2023 Feb;83(3):203-216. doi: 10.1007/s40265-022-01830-z. Epub 2023 Jan 18. PMID: 36652193.