TL;DR

ABO blood group is the most important blood group system in transfusion and organ transplantation medicine.

- ABO blood group antigens can be found on red cells, white cells, platelets and many circulating proteins. Transfusion incompatibility can cause acute intravascular hemolysis, renal failure and death.

- ABO blood group antigens can also be found on many tissues like the kidneys, heart, bowel, pancreas and lungs and incompatible transplantation leads to acute humoral rejection.

- Human ABO gene is found on chromosome 9 at the band 9q34.2.

- The ABO gene has three alleles: A, B, and O. A and B are co-dominant alleles while O is a recessive allele.

- The three antigens: A, B and H.

- Antibodies to A and B antigen develop in the first few months of life, without exposure to the red cell antigen known as ‘naturally occurring’ antibodies.

- ABO Rh test (blood group typing) can be done through tube, tile or gel cards method and further investigations include molecular typing and absorption-elution testing.

ABO Blood Group System Discovery

The history of the ABO blood group system dates back to 1900, when Karl Landsteiner, an Austrian physician and immunologist, made a groundbreaking discovery. Landsteiner mixed blood samples from different people and observed that some blood samples clumped together, while others did not. He realized that this was due to the presence of different antigens on the surface of red blood cells (RBCs). Landsteiner identified three different types of antigens, which he named A, B, and C (C was later renamed O for the German “Ohne”, meaning “without”).

Landsteiner’s discovery was significant because it led to the development of safe blood transfusions. Prior to Landsteiner’s work, blood transfusions were often fatal, as doctors did not understand why some blood samples were compatible with others and why some were not. Landsteiner’s discovery allowed doctors to match blood donors and recipients based on their blood type, which dramatically reduced the risk of adverse reactions. For this discovery he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1930.

In the years following Landsteiner’s discovery, other scientists made important contributions to our understanding of the ABO blood group system. In 1910, Alfred von Decastello and Adriano Sturli discovered the ABO incompatibility reaction. They found that if blood from a person with one blood group is transfused into a person with a different blood group, the antibodies in the recipient’s plasma will bind to the antigens on the donor’s RBCs and cause them to clump together. This clumping of RBCs can block blood vessels and lead to serious health problems, including death.

Here is a more detailed timeline of the history of the ABO blood group system:

- 1900: Karl Landsteiner discovers the ABO blood group system.

- 1910: Alfred von Decastello and Adriano Sturli discover the ABO blood group incompatibility reaction.

- 1927: Philip Levine and Rufus Stetson discover the Rh blood group system.

- 1940: Karl Landsteiner and Alexander Wiener discover the Kell blood group system.

- 1945: The Lewis blood group system is discovered.

- 1950: The Duffy blood group system is discovered.

- 1960: The Kidd blood group system is discovered.

- 1970: The MNS blood group system is discovered.

- 1980: The P blood group system is discovered.

- 1990: The Diego blood group system is discovered.

- 2000: The Cartwright blood group system is discovered.

Today, there are over 30 known blood group systems, each with its own unique set of antigens. The ABO blood group system remains the most important blood group system, but the other blood group systems are also important for blood transfusions and for the diagnosis and treatment of certain diseases.

Blood Group Antigens

The ABO blood group is the most important blood group system in transfusion and organ transplantation medicine. The ABO blood group antigens can be found on red cells, white cells, platelets and many circulating proteins and transfusion incompatibility can cause acute intravascular hemolysis, renal failure and death. The ABO blood group antigens can also be found on many tissues like the kidneys, heart, bowel, pancreas and lungs and incompatible transplantation leads to acute humoral rejection.

Red Blood Cell Membrane

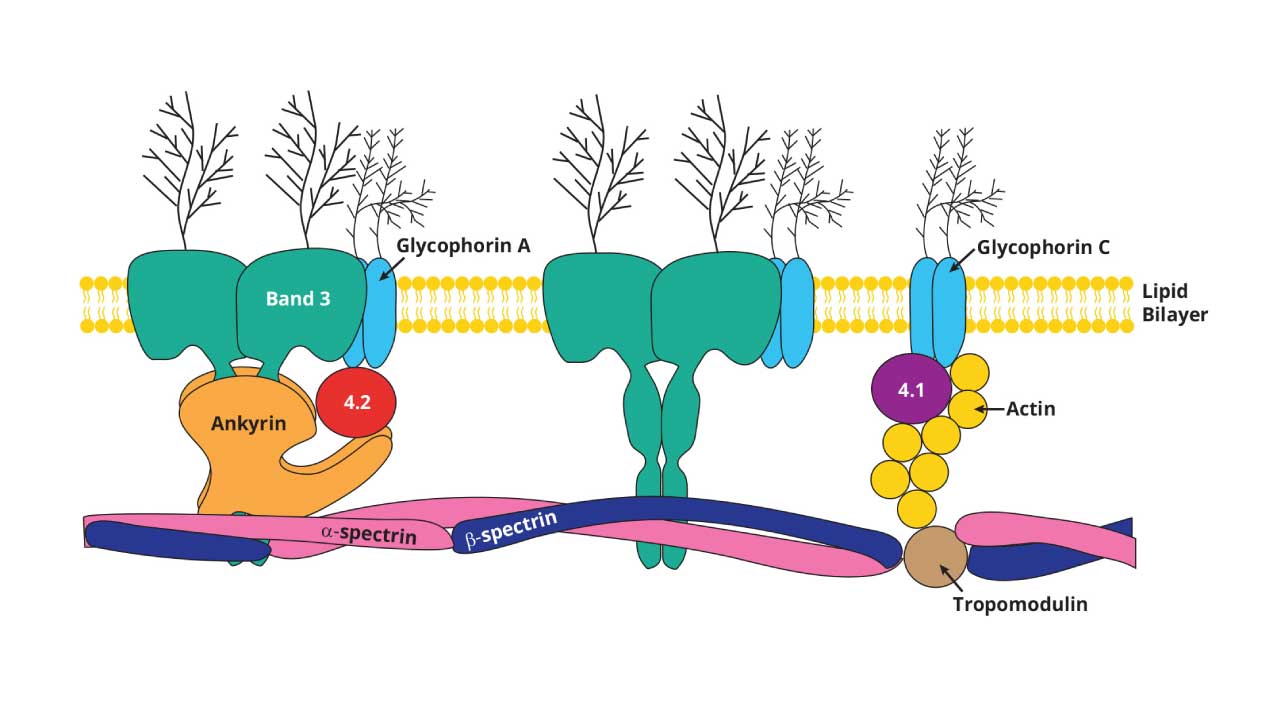

The red blood cell (RBC) membrane is a thin, flexible bilayer that surrounds and protects the RBC. It is composed of phospholipids, cholesterol, and proteins. The RBC membrane is also responsible for maintaining the shape and integrity of the RBC, as well as regulating the transport of molecules into and out of the cell.

The membrane is made up of 3 layers. The first layer consists of glycolipids, glycoproteins and carbohydrates. The second layer is a phospholipid bilayer and the third is a protein cytoskeleton. The vertical interaction mainly involves the glycolipids, glycoproteins and carbohydrates which stabilizes the lipid bilayer. Whereas, the horizontal interaction of the cytoskeleton supports the structural integrity of the RBC.

The RBC is a biconcave shaped cell of approximately 7.5 micron in diameter and 2 micron thick. The biconcave shape allows it to have a high surface to volume ratio for optimal gaseous exchange as well as to be able to be deformed to pass through microcapillaries of 3 micron in diameter. The membrane structure also provides permeability to allow water and electrolytes to exchange via the cation pumps.

The phospholipid bilayer has an asymmetric phospholipid distribution. It is semi-permeable and forms a barrier between the cytoplasm within the cell from the extracellular environment. This layer is also where glycolipids that carry RBC antigens and Rh antigens are embedded.

As for the membrane proteins, there are transmembrane proteins also known as integral proteins making up the ion transport channels like the Band 3 proteins, the glycophorins and aquaporins which transport water. The cytoskeleton are peripheral proteins which are located on the cytoplasmic surface of the lipid bilayer. The cytoskeleton is responsible for membrane elasticity and stability. It is anchored to the integral proteins via actin, spectrin, protein 4.1, band 4.2, ankyrin and other proteins that form nodes called the junctional complexes.

Location of Blood Group Antigens

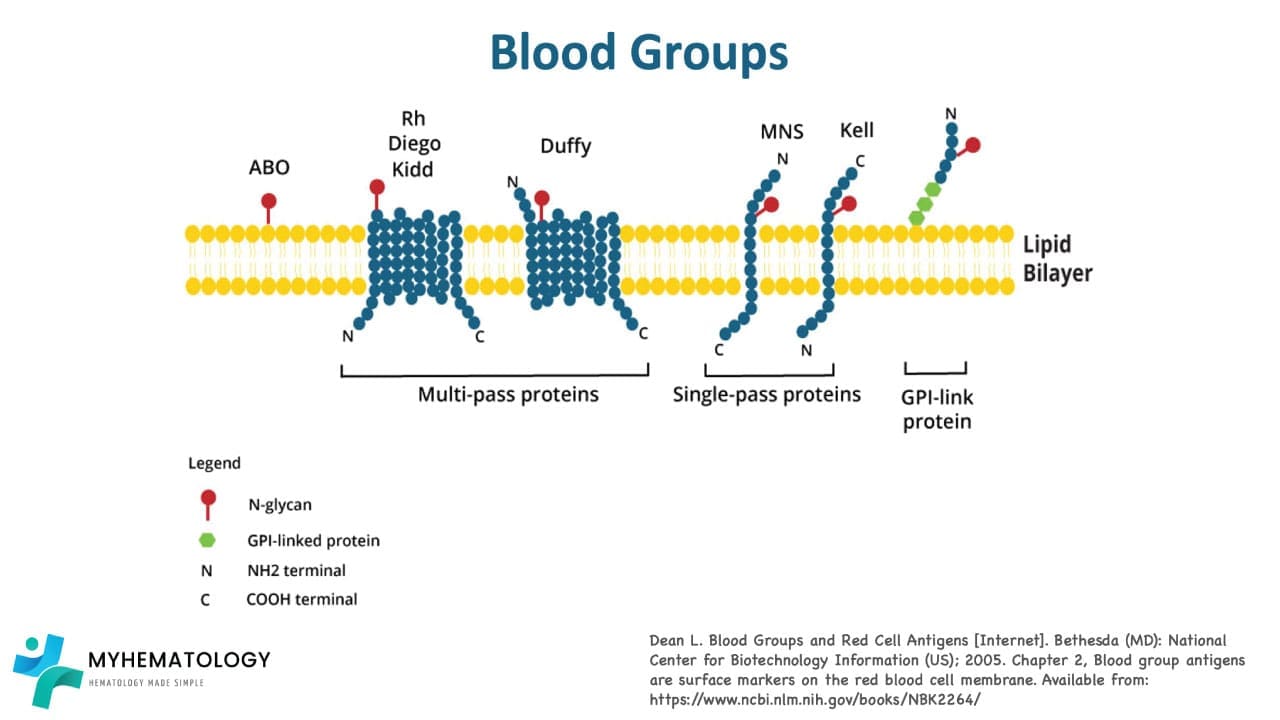

Blood group antigens are found on the surface of the RBC membrane. They are anchored to the membrane by a variety of mechanisms, including transmembrane proteins and glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchors.

Transmembrane proteins are proteins that have one or more sections that pass through the lipid bilayer of the RBC membrane. GPI anchors are small molecules that are embedded in the lipid bilayer and have a carbohydrate chain attached to them. The carbohydrate chain of the GPI anchor is covalently linked to the blood group antigen.

The type of anchoring mechanism that is used depends on the structure of the blood group antigen. For example, the ABO blood group antigens are all single-pass transmembrane proteins. The Rh blood group antigens, on the other hand, are multi-pass transmembrane proteins.

Importance of blood group antigens

Blood group antigens are important for a number of reasons. First, they allow the immune system to distinguish between self and non-self. If the immune system encounters RBCs with different blood group antigens, it will recognize them as foreign and attack them. This is why it is important to match blood donors and recipients based on their blood type.

Second, blood group antigens are involved in cell adhesion. Cell adhesion is the process by which cells stick together. Blood group antigens help RBCs to stick together and to adhere to the walls of blood vessels. This is important for maintaining the integrity of the vasculature and for preventing blood loss.

Third, blood group antigens are involved in transport. Some blood group antigens function as transporters for molecules such as gases, nutrients, and ions. This is important for maintaining the homeostasis of the body.

There are over 100 different red cell surface membrane proteins. Many of these are polymorphic and have come to attention because they induce clinically significant immune responses when transfused into mismatched recipients.

There are currently 30 blood group systems that are recognised. The clinical significance of blood groups in blood transfusion is that individuals who lack a particular blood group antigen may produce antibodies reacting with that antigen which may lead to a transfusion reaction. The different blood group antigens vary greatly in their clinical significance with the ABH and Rh groups being the most important.

These blood group genes have been identified and their genes are located on different chromosomes.

ABO Gene

The ABO blood group system is controlled by a single gene, the ABO gene, which is located on chromosome 9 at the band 9q34.2, contains 7 exons. The ABO gene has three alleles: A, B, and O. The A and B alleles are codominant, meaning that both alleles are expressed equally if an individual has two copies of them. The O allele is recessive, meaning that it is only expressed if an individual has two copies of it.

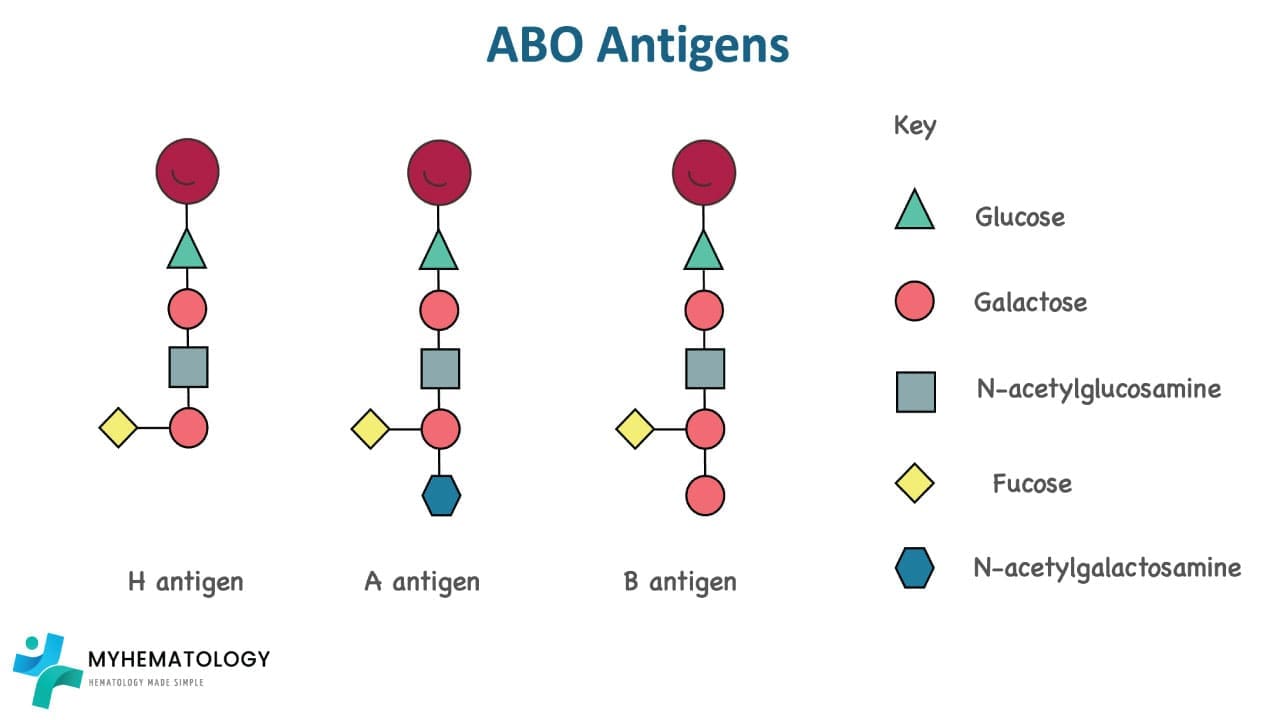

The ABO blood group gene encodes a glycosyltransferase enzyme, which is an enzyme that adds sugar molecules to proteins and lipids. The type of glycosyltransferase enzyme that is produced depends on the ABO allele that an individual has. People with the A allele produce an A glycosyltransferase enzyme, which adds an N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) sugar molecule to the H antigen. People with the B allele produce a B glycosyltransferase enzyme, which adds a galactose (Gal) sugar molecule to the H antigen. People with the O allele produce a non-functional glycosyltransferase enzyme, which does not add any sugar molecules to the H antigen.

The H antigen is a precursor antigen that is present on the surface of all RBCs. It is synthesized from glucose molecules by a series of enzymatic reactions. The ABO glycosyltransferase enzymes add the final sugar molecule to the H antigen to produce the A, B, or O antigen.

The ABO antigens, designated as A, B, and O, are composed of oligosaccharides, complex carbohydrate structures attached to the surface of red blood cells. Their distinctive molecular configurations arise from subtle variations in the arrangement of these carbohydrate chains.

Individuals produce antibodies to the antigen that they lack on their red cells. Landsteiner’s law states that, for whichever ABO blood group antigen is not present on the red cells, the corresponding antibody is found in the plasma. Antibodies to A and B antigen develop in the first few months of life, without exposure to the red cell antigen, as a result of environmental exposure to bacteria. They are referred to as ‘naturally occurring’ antibodies. ABO blood group antibodies are usually IgM but may be IgG.

The ABO blood group antigens are important for blood transfusions and for preventing hemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN). HDN is a condition that can occur when a pregnant woman has a different blood type than her fetus. If the mother’s antibodies cross the placenta and bind to the fetus’ RBCs, the fetus’ RBCs can be destroyed. This can lead to anemia, jaundice, and even death in the fetus.

The genetics of the ABO blood group system are complex, but they are well understood. The ABO blood group gene is a highly polymorphic gene, meaning that there are many different variations of the gene. These variations can affect the expression of the ABO blood group antigens and can also lead to the production of abnormal ABO blood group antigens.

| ABO allele | ABO glycosyltransferase enzyme | ABO antigen | Blood type |

| A | A glycosyltransferase | A antigen | A |

| B | B glycosyltransferase | B antigen | B |

| O | Non-functional glycosyltransferase | H antigen | O |

Naturally Occurring Antibodies

Naturally occurring antibodies are antibodies that are produced by the immune system without any prior exposure to a foreign antigen. They are also known as pre-immune antibodies or regular antibodies. Naturally occurring antibodies are found in the blood serum of all healthy individuals and play an important role in defending the body against infection.

One of the most important groups of naturally occurring antibodies is the ABO blood group antibodies. ABO blood group antibodies are antibodies that are directed against the A and B antigens of the ABO blood group system. Everyone has ABO blood group antibodies in their blood serum, but the type of ABO blood group antibodies that a person has depends on their blood type. People with blood type A have anti-B antibodies in their serum, people with blood type B have anti-A antibodies in their serum, people with blood type AB have no ABO blood group antibodies in their serum, and people with blood type O have both anti-A and anti-B antibodies in their serum.

ABO blood group antibodies are produced in response to exposure to ABO blood group antigens from the environment. For example, people with blood type A are exposed to B antigens from food, bacteria, and other environmental sources. This exposure stimulates their immune system to produce anti-B antibodies.

ABO blood group antibodies are important for preventing transfusion reactions and hemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN). Transfusion reactions occur when a person is transfused with blood that is incompatible with their blood type. The ABO blood group antibodies in the recipient’s blood serum bind to the A or B antigens on the donor’s RBCs, causing them to clump together and lyse. This can lead to serious health problems, including death.

HDN is a condition that can occur when a pregnant woman has a different blood type than her fetus. If the mother’s ABO blood group antibodies cross the placenta and bind to the fetus’s RBCs, the fetus’ RBCs can be destroyed. This can lead to anemia, jaundice, and even death in the fetus.

ABO blood group antibodies are also involved in other immunological processes, such as inflammation and immunity to infection. For example, ABO blood group antibodies can activate complement, which is a group of proteins that play a role in killing bacteria and other pathogens. ABO blood group antibodies can also bind to certain types of viruses and bacteria, preventing them from infecting cells.

Inheritance Pattern of the ABO Blood Group System

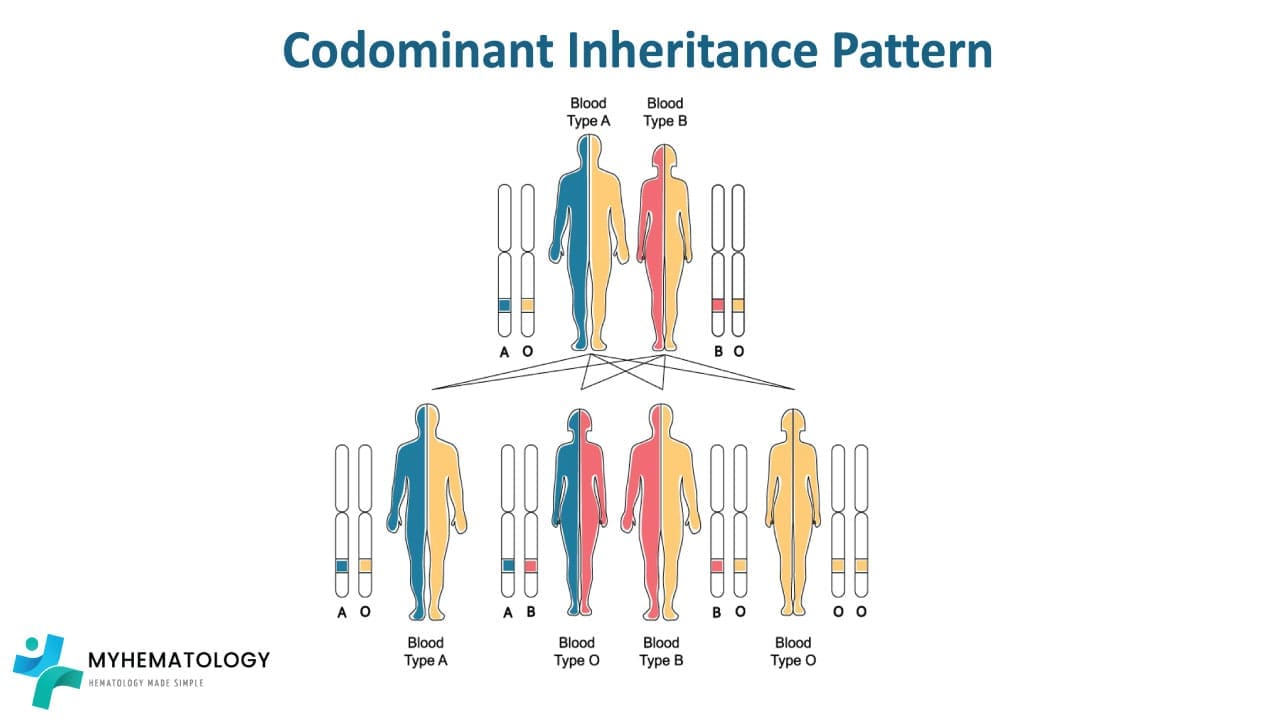

The inheritance pattern for the ABO blood group system is codominant with incomplete penetrance. This means that both alleles of the ABO gene are expressed equally, and that the resulting blood type is a combination of the two alleles. However, in some cases, the expression of the ABO blood group alleles may be incomplete, resulting in a weaker expression of the blood group antigens.

The ABO gene has three alleles: A, B, and O. The A and B alleles are codominant, meaning that both alleles are expressed equally if an individual has two copies of them. The O allele is recessive, meaning that it is only expressed if an individual has two copies of it.

The following table shows the possible blood types and inheritance patterns for the ABO blood group system.

| Parent 1 | Parent 2 | Possible blood types in offspring |

| A | A | A, AB |

| A | B | A, AB, B |

| A | O | A, O |

| B | B | B, AB |

| B | O | B, O |

| O | O | O |

In some cases, the expression of the ABO alleles may be incomplete. This can happen when a person has a mutation in the ABO gene or when they have another gene that interferes with the expression of the ABO gene. Incomplete penetrance of the ABO alleles can result in a weaker expression of the blood group antigens. For example, a person with the A allele may have a weaker expression of the A antigen, resulting in a blood type that is closer to O than A.

By understanding the inheritance pattern for the ABO blood group system, doctors can better match blood donors and recipients and can also screen pregnant women for HDN.

A and B blood subgroups

The ABO blood group system is classified into four main types: A, B, AB, and O. However, there are also a number of subgroups of blood group A and B. These subgroups are caused by mutations in the ABO gene that affect the expression or structure of the A and B antigens.

Subgroups of blood group A

The subgroups of blood group A are:

- A1: This is the most common subgroup of blood group A. People with blood type A1 have strongly expressed A antigens on their RBCs.

- A2: People with blood type A2 have weakly expressed A antigens on their RBCs. This is due to a mutation in the ABO gene that reduces the amount of A antigen that is produced.

- Ax: People with blood type Ax have a very rare type of A antigen on their RBCs. This antigen is not recognized by most anti-A antibodies.

- A3: People with blood type A3 have a very rare type of A antigen on their RBCs that is not recognized by some anti-A antibodies.

Subgroups of blood group B

The subgroups of blood group B are:

- B1: This is the most common subgroup of blood group B. People with blood type B1 have strongly expressed B antigens on their RBCs.

- B2: People with blood type B2 have weakly expressed B antigens on their RBCs. This is due to a mutation in the ABO gene that reduces the amount of B antigen that is produced.

- Bx: People with blood type Bx have a very rare type of B antigen on their RBCs. This antigen is not recognized by most anti-B antibodies.

- B3: People with blood type B3 have a very rare type of B antigen on their RBCs that is not recognized by some anti-B antibodies.

There are also others like Am, Ay, Ael, Aend, Bm, By, Bel and Bend that are not discussed here.

Importance of A and B subgroups

ABO blood group subgroups can affect ABO Rh test in a number of ways.

- Weak reactions: People with weak ABO subgroups, such as A2 or B2, may have weaker reactions to anti-A or anti-B antibodies during ABO Rh tests. This can make it more difficult to accurately determine the person’s blood type.

- Mixed field reactions: People with mixed field ABO subgroups, such as A3 or B3, may have both A and B antigens on their red blood cells. This can cause them to react to both anti-A and anti-B antibodies during ABO Rh tests. This is known as a mixed field reaction.

- Discrepancies between forward and reverse typing: In some cases, there may be a discrepancy between the results of forward and reverse blood typing. This can happen when a person has a rare ABO subgroup or when the blood sample is not handled properly.

Blood bank technicians are trained to recognize these atypical reactions and to take steps to ensure that the blood type is accurately determined. In some cases, additional testing may be needed, such as molecular testing or absorption-elution testing.

Understanding Secretor Status: The FUT2 Gene

While we usually think of ABO blood group antigens as being “stuck” to the surface of red blood cells, for about 80% of the population, these antigens are also floating freely in their bodily fluids (saliva, tears, sweat, and digestive juices). These individuals are known as Secretors.

The Genetic Basis: FUT1 vs. FUT2

The production of ABO blood group antigens in different tissues is controlled by two distinct but related genes:

- FUT1 (H Gene): This gene is active in the erythroid tissue. It codes for the H-antigen on red blood cells. Almost everyone has this gene.

- FUT2 (Se Gene): This gene is active in secretory tissues (like salivary glands and mucosal linings). It codes for an enzyme (alpha-1,2-fucosyltransferase) that places the H-antigen precursor into secretions. Once the H-antigen is secreted, the A or B enzymes (if present) can add their specific sugars to it.

Secretor vs. Non-Secretor

- Secretors (SeSe or Sese): Approximately 80% of people. They have at least one functional FUT2 allele. If they are Blood Type A, they will have A and H antigens in their saliva.

- Non-Secretors (sese): Approximately 20% of people. They inherit two non-functional alleles. Even if they are Blood Type A, their saliva will contain no A, B, or H antigens.

Why is this Clinically Significant?

- Forensic Science: Historically, secretor status allowed forensic scientists to determine the blood type of a suspect from a cigarette butt, a licked envelope, or a perspiration stain found at a crime scene.

- Susceptibility to Infection: * Norovirus: “Non-secretors” are famously resistant to many strains of the “stomach flu” (Norovirus). The virus needs the ABO/H antigens in the gut lining to “dock” onto and infect the cells.

- H. pylori: Secretor status can influence the risk of peptic ulcers, as certain bacteria use these secreted sugars to adhere to the stomach wall.

- Diagnostic Utility: In the blood bank, testing saliva for antigens (neutralization studies) can help resolve difficult ABO grouping discrepancies or identify the rare Bombay Phenotype (who are always non-secretors because they lack the H-substance entirely).

The Bombay Phenotype (Oh)

First discovered in 1952 in Bombay (now Mumbai), India, by Dr. Y.M. Bhende, this phenotype occurs in about 1 in 10,000 individuals in India and 1 in 1,000,000 individuals in Europe.

The H-Antigen

The A and B antigens require a foundation called the H-antigen.

- Normal Physiology: The FUT1 gene codes for an enzyme that adds a fucose sugar to a precursor chain, creating the H-antigen. Only then can the A or B enzymes add their specific sugars.

- The Bombay Phenotype: Individuals with the Bombay phenotype inherit two recessive ‘h’ alleles (hh). They lack the FUT1 gene and therefore cannot produce the H-antigen foundation.

Why it Mimics Blood Type O

In standard laboratory “Forward Grouping,” a Bombay individual will test as Type O because they have no H-antigen, they cannot create A or B antigens.

Anti-H Antibodies

The clinical danger lies in the “Reverse Grouping” (Plasma testing).

- Type O individuals: Have H-antigen on their cells, so they do not make Anti-H.

- Bombay individuals: Because their bodies have never seen the H-antigen, they produce a potent, naturally occurring Anti-H antibody.

This Anti-H is a strong IgM antibody that reacts at 37°C. It will attack and destroy any blood that has H-antigen on it. Since Type A, B, AB, and O all have H-antigen, a Bombay individual can only receive blood from another Bombay individual.

Type O vs. Bombay Phenotype

| Feature | Blood Type O | Bombay Phenotype (Oh) |

| Genotype | OO / HH or Hh | Any ABO / hh |

| H-Antigen on RBCs | Present (Highest amount) | Absent |

| Forward Type | Appears as O | Appears as O |

| Antibodies in Plasma | Anti-A, Anti-B | Anti-A, Anti-B, Anti-H |

| Transfusion Options | Can receive any Type O | Only Bombay blood |

| Secretor Status | Usually Secretor (if Se gene present) | Always Non-secretor |

The Para-Bombay Phenotype

While the classic Bombay phenotype lacks the H-antigen entirely (both on red cells and in secretions), the Para-Bombay phenotype is a more subtle variation. In Para-Bombay, the FUT1 gene (responsible for red cell antigens) is mutated/silenced, but the FUT2 gene (the secretor gene) remains functional. Because FUT2 is working, the body can still produce small amounts of H-substance in the plasma. This H-substance can be “picked up” or adsorbed onto the red blood cells from the plasma.

Unlike the “totally bald” cells of a classic Bombay, Para-Bombay red cells show very weak expression of A, B, or H antigens. They often appear as Type O in routine forward grouping, but a more sensitive test (like adsorption-elution) will reveal the hidden antigens.

They typically have a weaker Anti-H antibody compared to classic Bombay individuals, making them slightly less prone to catastrophic transfusion reactions, though they still require specialized blood matching.

ABO Blood Group Typing using ABO Rh Tests

ABO Rh tests, also called ABO blood group typing are commonly used to determine the presence of A, B, or neither of these antigens (type O), while the Rh test looks for the Rh factor (positive or negative). Both ABO and Rh tests are performed together because they provide complementary information crucial for safe blood transfusions. A mismatch in either system during a transfusion can trigger a severe immune reaction. Testing for both ABO and Rh together ensures compatibility on both these levels, minimizing the risk of transfusion reactions and guaranteeing the recipient receives safe blood.

The laboratory investigations for ABO blood grouping are:

- Forward typing: This is a test to determine the presence of A and B antigens on the surface of red blood cells (RBCs). The test is performed by mixing a drop of blood with a drop of anti-A serum and a drop of anti-B serum. If the blood clumps with either serum, it indicates that the corresponding antigen is present on the RBCs.

- Reverse typing: This is a test to determine the presence of anti-A and anti-B antibodies in the serum. The test is performed by mixing a drop of serum with a drop of A RBCs and a drop of B RBCs. If the serum clumps with either RBC type, it indicates that the corresponding antibody is present in the serum.

The ABO Rh test (blood group typing) tile method, the tube method, and the gel card method are three common methods used for forward and reverse typing.

Tile method

The tile method is a simple and inexpensive method for ABO Rh test (blood group typing). It is often used in field settings, such as blood banks and emergency rooms.

To perform the tile method, a drop of the patient’s blood is placed on a tile or glass slide. A drop of anti-A serum and a drop of anti-B serum are then added to the blood drop. The tile is gently tilted back and forth to mix the blood and serum.

If the blood clumps with either serum, it indicates that the corresponding antigen is present on the red blood cells (RBCs). For example, if the blood clumps with anti-A serum, it indicates that the patient has blood group A.

The ABO Rh test (blood group typing) tile method is a quick and easy way to determine blood type, but it is not as accurate as the other two methods. This is because the tile method is subjective, has a high-risk of contamination and relies on the visual interpretation of the results.

Tube method

The tube method is a more accurate method for ABO Rh test (blood group typing) than the tile method. It is often used in clinical laboratories.

To perform the ABO Rh test tube method, a small amount of the patient’s blood is placed in a tube. A drop of anti-A serum and a drop of anti-B serum are then added to the tube. The tube is then incubated at 37 degrees Celsius for 15 minutes.

After incubation, the tube is centrifuged to spin down the RBCs. The plasma is then removed and the RBCs are resuspended in saline. The RBCs are then examined for clumping.

If the blood clumps with either serum, it indicates that the corresponding antigen is present on the RBCs. The tube method is more accurate than the tile method because it involves incubation and centrifugation. This helps to ensure that the RBCs are fully exposed to the serum and that any clumping is visible.

Gel card method

The gel card method is a newer method for ABO Rh test (blood group typing). It is a more rapid and efficient method than the tube method.

To perform the gel card method, a drop of the patient’s blood is placed on a gel card. The gel card contains antibodies to A and B antigens. The gel card is then incubated at room temperature for 5-10 minutes.

After incubation, the gel card is examined for clumping. If the blood clumps with either antibody, it indicates that the corresponding antigen is present on the RBCs.

The gel card method is a rapid and accurate method for ABO Rh test (blood group typing). It is often used in blood banks and emergency rooms.

Comparison of the three ABO Rh test methods

The following table compares the three methods for ABO Rh test:

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Tile method | Simple and inexpensive | Subjective and not as accurate as the other two methods |

| Tube method | More accurate than the tile method | More time-consuming and expensive than the gel card method |

| Gel card method | Rapid and accurate | More expensive than the tile method |

The best method for ABO Rh test (blood group typing) depends on the specific setting and needs. For example, the tile method is often used in field settings where a quick and easy result is needed. The ABO Rh test (blood group typing) tube method is often used in clinical laboratories where accuracy is more important than speed. The ABO Rh test (blood group typing) gel card method is often used in blood banks and emergency rooms where speed and accuracy are both important.

In addition to forward and reverse typing, other laboratory investigations for ABO blood grouping may include:

- Molecular testing: This type of testing can be used to detect genetic mutations that affect the production of ABO blood group antigens or antibodies.

- Absorption-elution testing: This type of testing is used to identify rare ABO blood group subgroups or to resolve discrepancies between forward and reverse typing.

ABO Blood Group Transfusion Compatibility

In transfusion medicine, the goal is simple but absolute: The recipient’s antibodies must not attack the donor’s antigens. A mismatch of ABO blood group leads to Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction (AHTR), where donor red cells are destroyed intravascularly, potentially leading to disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), renal failure, and death.

The Red Blood Cell (RBC) Compatibility Rule

When transfusing packed red blood cells, we are worried about the recipient’s plasma antibodies reacting with the donor’s red cell antigens.

| Recipient Blood Type | Antigens on Donor RBCs that are SAFE | Donor RBC Choice (In Order of Preference) |

| Type A | A, O | A, O |

| Type B | B, O | B, O |

| Type AB | A, B, AB, O | AB (Recipient), A, B, O |

| Type O | O | O only |

- The Universal Red Cell Donor: Type O (specifically O Negative). Because Type O cells lack A and B antigens, there is nothing for the recipient’s anti-A or anti-B to attack.

- The Universal Red Cell Recipient: Type AB. Because these individuals lack anti-A and anti-B antibodies, they can safely receive red cells of any ABO type.

The Plasma Compatibility Rule (The “Flip” Rule)

In plasma transfusion (FFP – Fresh Frozen Plasma), the logic is reversed. We are now worried about the donor’s plasma antibodies reacting with the recipient’s red cell antigens.

| Recipient Blood Type | Antibodies in Donor Plasma that are SAFE | Donor Plasma Choice |

| Type A | Anti-B, None | A, AB |

| Type B | Anti-A, None | B, AB |

| Type AB | None | AB only |

| Type O | Anti-A, Anti-B, None | O, A, B, AB |

- The Universal Plasma Donor: Type AB. Their plasma contains neither anti-A nor anti-B, making it safe for any recipient. This is the opposite of the red cell rule.

- The Universal Plasma Recipient: Type O. Since Type O red cells have no A or B antigens, any plasma (even plasma containing anti-A and anti-B) is safe for them.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Can your blood type change over time?

Generally, no. However, rare exceptions occur in cases of bone marrow transplants (where the recipient adopts the donor’s blood type) or certain types of leukemia that can weaken antigen expression.

Why is Type O the “Universal Donor” for red cells?

Type O red cells lack both A and B antigens. Therefore, a recipient’s anti-A or anti-B antibodies have nothing to attack on the surface of these donor cells.

What happens if I am given the wrong blood type?

This causes an Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction. Your antibodies immediately attack the donor cells, causing them to burst. This can lead to kidney failure, shock, and is a medical emergency.

Why don’t we have “naturally occurring” antibodies against the RhD antigen?

Unlike ABO blood group antigens, which are similar in structure to common environmental bacteria (leading to early “natural” sensitization), the RhD blood group antigen is unique to human red cells. Exposure must occur via blood-to-blood contact (transfusion or pregnancy) to trigger antibody production.

Is the H-antigen the same as Type O?

Not exactly. The H-antigen is the precursor “foundation” for A and B. People with Type O blood have the H-antigen but haven’t added A or B sugars to it. Only people with the rare “Bombay Phenotype” lack the H-antigen entirely.

Can a person be a secretor for some antigens but not others?

No. Secretor status is an “all or nothing” genetic switch for the H-substance. If you are a secretor, you will secrete whatever ABO blood group antigens your genotype dictates (A, B, or H). If you are a non-secretor, you will not secrete any of them.

Can a Bombay person have ‘A’ or ‘B’ genes?

Yes! A Bombay individual might genetically be Type A or B, but because they lack the “H” foundation, those A or B sugars have nowhere to attach. If they pass their genes to a child who inherits a normal H gene from the other parent, the child could “miraculously” be Type A or B.

Glossary of Related Medical Terms

- Agglutination: The clumping of particles (like red blood cells) when an antigen is mixed with its corresponding antibody.

- Allo-antibody: An antibody produced by one individual that reacts with an antigen found in another individual of the same species.

- Allele: One of two or more alternative forms of a gene that arise by mutation and are found at the same place on a chromosome.

- Co-dominant: A relationship between two versions of a gene where individuals receive one version of a gene, called an allele, from each parent. Neither allele is even partially masked by the other.

- Genotype: The genetic constitution of an individual organism (e.g., AO, BB).

- Hemolysis: The rupture or destruction of red blood cells.

- Immunogenicity: The ability of a foreign substance, such as an antigen, to provoke an immune response in the body.

- Locus: The specific physical location of a gene or DNA sequence on a chromosome.

- Phenotype: The observable physical properties of an organism (e.g., Blood Type A).

- Sensitization: The process by which the immune system produces an antibody in response to a foreign antigen (usually after transfusion or pregnancy).

- Secretor: An individual who expresses ABO(H) blood group antigens in their bodily fluids due to a functional FUT2 gene.

- Neutralization: A laboratory technique where saliva is used to “block” or neutralize antibodies, helping to identify specific blood group substances.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Groot HE, Sierra LEV, Said MA, Lipsic E, Karper JC, van der Harst P. Genetically Determined ABO Blood Group and its Associations With Health and Disease. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2020;40:830–838.

- Abegaz SB. Human ABO Blood Groups and Their Associations with Different Diseases. Biomed Res Int. 2021 Jan 23;2021:6629060. doi: 10.1155/2021/6629060. PMID: 33564677; PMCID: PMC7850852.

- Dean L. Blood Groups and Red Cell Antigens [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2005. Chapter 5, The ABO blood group.

- Yamamoto F. ABO+logy: Bioscience of the ABO Blood Groups for High School/College Students & Adults (2023).

- Romanos-Sirakis EC, Desai D. ABO Blood Group System. [Updated 2025 Apr 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK580518/