TL;DR

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common and aggressive type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, a fast-growing cancer of B-lymphocytes.

- Epidemiology ▾: It is the most common non-Hodgkin lymphoma worldwide, with incidence increasing with age. Risk factors include immunosuppression (like HIV/AIDS), autoimmune diseases, and certain viral infections (Epstein-Barr Virus and Hepatitis C).

- Pathophysiology ▾: The disease arises from transformed B-lymphocytes and can be categorized into two main subtypes: Germinal Center B-cell-like (GCB) and Activated B-cell-like (ABC).

- Clinical Presentation ▾: The most common symptom is a rapidly enlarging lymph node or mass, often accompanied by B symptoms (unexplained fever, drenching night sweats, and weight loss).

- Diagnosis and Staging ▾: A diagnosis is confirmed with an excisional biopsy and immunohistochemistry. Staging involves a PET-CT scan, with the International Prognostic Index (IPI) used to assess risk and guide treatment.

- Treatment ▾: The standard first-line treatment is the R-CHOP regimen, a combination of five agents that has a high potential for cure. Patients with limited-stage disease may also receive radiation therapy.

- Relapsed or Refractory Disease ▾: For patients who relapse or don’t respond to initial treatment, options include salvage chemotherapy, autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT), and newer immunotherapies like CAR T-cell therapy and bispecific antibodies.

- Prognosis: While aggressive, DLBCL is a highly curable disease, especially with modern treatment. The prognosis depends on factors like the IPI score and molecular subtype, with “double-hit” and “triple-hit” lymphomas having a poorer prognosis.

*Click ▾ for more information

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in adults. It is an aggressive, fast-growing cancer of the B lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell crucial to the immune system. The “diffuse” term describes how the malignant cells are spread out throughout the lymph node or tissue, while “large” refers to the size of the neoplastic B cells.

This article provides a comprehensive overview of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), from its pathophysiology to current clinical management.

Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) Epidemiology & Risk Factors

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma worldwide, accounting for approximately 25-30% of all cases. Its incidence varies globally, but it is generally higher in developed countries. In the United States, over 18,000 new cases are diagnosed annually.

While diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) can affect people of any age, its incidence increases significantly with age. The median age at diagnosis is around 64 years. There is a slight male predominance, with males having a higher incidence rate than females.

The exact cause of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is often unknown, but several risk factors have been identified. These are typically related to conditions that compromise the immune system or cause chronic inflammation.

- Immunosuppression: A weakened immune system is a major risk factor. This is seen in:

- HIV/AIDS: Individuals with HIV/AIDS are at a significantly higher risk of developing diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), a condition known as AIDS-related lymphoma.

- Post-Transplant Lymphoproliferative Disorder (PTLD): Patients who have undergone solid organ or stem cell transplantation and are on immunosuppressive therapy have a higher risk, often linked to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection.

- Inherited Immunodeficiency Syndromes: Rare genetic disorders like Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome and common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) are also associated with an increased risk.

- Autoimmune Diseases: The chronic immune stimulation and inflammation associated with certain autoimmune disorders can increase the risk of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Key examples include:

- Sjögren’s syndrome

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

- Rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

- Viral Infections: Certain viruses are strongly linked to the development of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

- Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV): EBV infection is a known risk factor, particularly in immunosuppressed individuals and in specific subtypes like EBV-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) of the elderly.

- Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) and Hepatitis B Virus (HBV): Chronic infection with these viruses has been associated with an increased risk of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), especially in certain geographic regions.

- Human Herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8): This virus is primarily associated with primary effusion lymphoma, a rare subtype of large B-cell lymphoma.

- Other Potential Risk Factors: While less common, there are other associations.

- Environmental Exposures: Some studies have suggested links to certain chemicals like pesticides.

- Family History: A family history of lymphoma, while not a strong risk factor, can slightly increase an individual’s risk.

Pathophysiology of Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL)

The development of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is a multi-step process driven by genetic mutations that disrupt normal B-cell development and proliferation. While the exact cause is often unknown, the disease arises from the malignant transformation of a mature B-cell at different stages of its development.

This has led to the identification of distinct molecular subtypes, primarily based on gene expression profiling (GEP).

- Germinal Center B-cell-like (GCB) DLBCL: This subtype originates from a B-cell in the germinal center of a lymph node. It is often associated with translocations involving the BCL2 and BCL6 genes. The GCB subtype generally has a better prognosis with standard therapy.

- Activated B-cell-like (ABC) DLBCL: This subtype arises from a post-germinal center B-cell. It is characterized by chronic activation of the B-cell receptor (BCR) and NF-κB signaling pathways. The ABC subtype is typically more resistant to standard chemotherapy and has a less favorable prognosis.

Beyond these two main subtypes, ongoing research has identified additional genetic subgroups and markers, such as rearrangements in the MYC gene (a “double-hit” or “triple-hit” lymphoma), which are associated with very aggressive disease and poor outcomes.

Key Genetic Aberrations and Oncogenic Pathways

The hallmark of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is a series of genetic alterations that lead to uncontrolled cell proliferation and survival. The most common and clinically significant of these are translocations and mutations in key oncogenes and signaling pathways.

MYC, BCL2, and BCL6 Gene Translocations

- MYC: The MYC gene is a powerful oncogene that regulates cell growth, metabolism, and apoptosis. In diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), a chromosomal translocation, most commonly the t(8;14), places the MYC gene under the control of an immunoglobulin enhancer, leading to its massive overexpression. This drives rapid, uncontrolled cell proliferation and is associated with a highly aggressive clinical course.

- BCL2: The BCL2 gene is an anti-apoptotic protein, meaning its function is to prevent programmed cell death. The t(14;18) translocation is a key genetic event in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and a frequent finding in its precursor, follicular lymphoma. This translocation causes constant, high-level expression of the BCL2 protein, giving lymphoma cells a survival advantage and making them resistant to chemotherapy.

- BCL6: The BCL6 gene is a master transcriptional repressor that is crucial for the normal development of germinal center B-cells. Translocations involving BCL6, particularly t(3;14), disrupt its normal function, preventing the differentiation of B-cells and allowing them to persist in an abnormal, proliferative state.

Double-Hit and Triple-Hit Lymphomas

Some of the most aggressive diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCLs) are characterized by simultaneous genetic rearrangements involving two or more of these genes.

- Double-Hit Lymphoma (DHL): This is defined by a chromosomal rearrangement of MYC along with a rearrangement of either BCL2 or BCL6.

- Triple-Hit Lymphoma (THL): This includes rearrangements of all three genes: MYC, BCL2, and BCL6. These “hit” lymphomas are considered high-grade B-cell lymphomas and have a significantly worse prognosis than other diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCLs) subtypes, often requiring more intensive treatment regimens.

NF-κB Pathway Activation

The Nuclear Factor-kappa B (NF-κB) pathway is a central signaling pathway that regulates cell survival, proliferation, inflammation, and immune responses. In normal cells, this pathway is tightly controlled, but in the Activated B-cell-like (ABC) subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCLs), it becomes chronically and aberrantly activated. This constant activation provides a powerful pro-survival signal to the lymphoma cells, allowing them to resist apoptosis. Chronic NF-κB activation in ABC DLBCL is often a result of genetic mutations in genes like MYD88, which regulate the pathway.

This molecular heterogeneity underscores why a one-size-fits-all approach is not effective and highlights the need for a personalized medicine approach.

Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) Symptoms

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) typically presents as a rapidly enlarging mass, most commonly in a lymph node in the neck, armpit, or groin. However, it can also arise in extranodal sites (outside of lymph nodes), such as the gastrointestinal tract, bones, skin, or central nervous system. Common symptoms include:

- B-Symptoms: These are systemic symptoms that are common in many lymphomas and include:

- Unexplained fever

- Drenching night sweats

- Unexplained weight loss of more than 10% of body weight over six months

- Lymphadenopathy: The most common sign is the painless, rapid enlargement of one or more lymph nodes. This can occur in the neck, armpit, or groin.

- Extranodal Involvement: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is known for its ability to arise outside of the lymph nodes. This is called extranodal disease and can lead to symptoms specific to the affected organ. Common sites include the gastrointestinal tract (causing abdominal pain or bleeding), bone marrow (leading to cytopenias), testes, or central nervous system (causing neurological symptoms).

- Symptoms of Compression: The lymphoma mass can grow large enough to compress nearby organs or structures, causing pain, swelling, or other issues depending on the location. For example, a mass in the chest could cause a cough or difficulty breathing.

Laboratory Investigations and Staging

The diagnostic process for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is a systematic approach aimed at confirming the diagnosis, characterizing the disease, and determining its extent (staging). This information is important for guiding treatment decisions and assessing prognosis.

Initial Laboratory Investigations

A comprehensive initial workup is essential to establish a baseline and identify potential complications.

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) with differential: To check for anemia, leukopenia, or thrombocytopenia, which may indicate bone marrow involvement.

- Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) and uric acid: Elevated levels of LDH are common in aggressive lymphomas and are a key component of the International Prognostic Index (IPI). High uric acid levels may indicate rapid tumor cell turnover and a risk of tumor lysis syndrome.

- Liver and kidney function tests: To assess organ function, which can be affected by the disease or be a consideration for chemotherapy.

- Viral serology: Screening for HIV, Hepatitis B (HBV), and Hepatitis C (HCV) is critical, as these infections can influence treatment choice and prognosis.

Essential Diagnostic Procedure

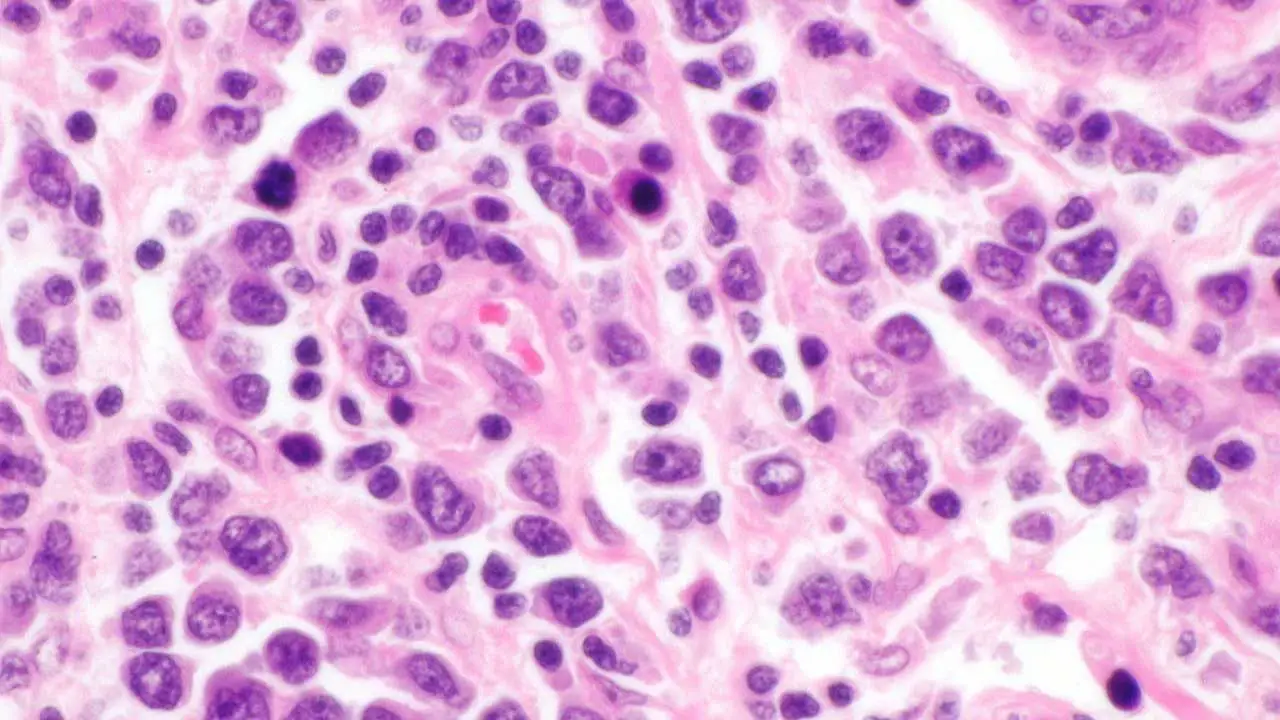

- Excisional Biopsy: This is the gold standard for diagnosing diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). A full lymph node or mass is surgically removed and sent for a detailed histopathological analysis. A fine-needle aspiration (FNA) is generally insufficient for a definitive diagnosis because it does not provide enough tissue to assess the architecture of the lymphoma, which is a key diagnostic criterion.

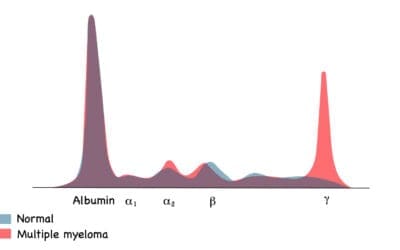

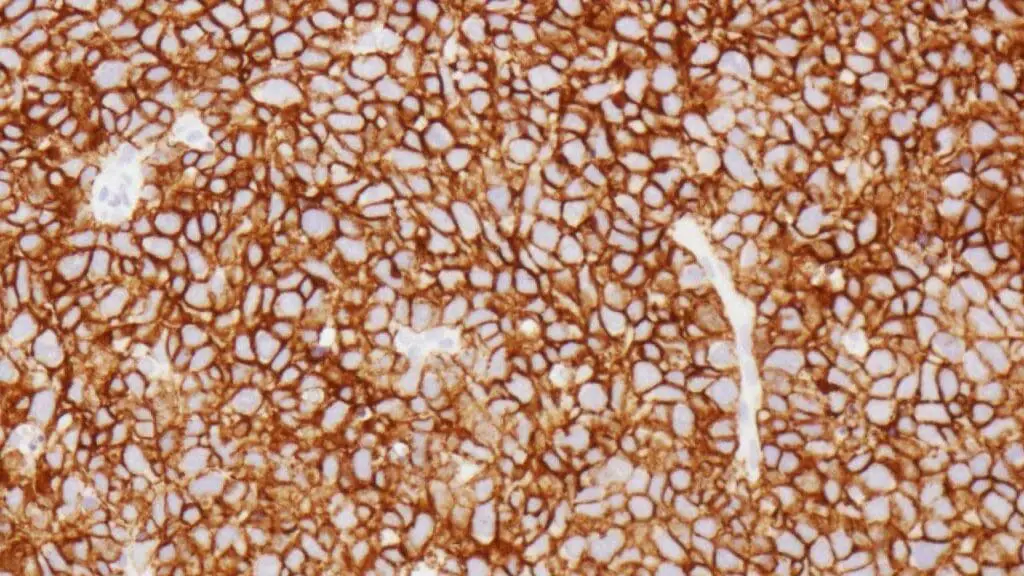

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC): This technique is performed on the biopsy sample to confirm the B-cell lineage and identify specific markers. A positive finding for CD20 is characteristic of most diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCLs) and is a prerequisite for treatment with the targeted therapy, Rituximab. The Ki-67 proliferation index is also assessed, as a high value indicates a rapidly dividing tumor.

Staging Investigations

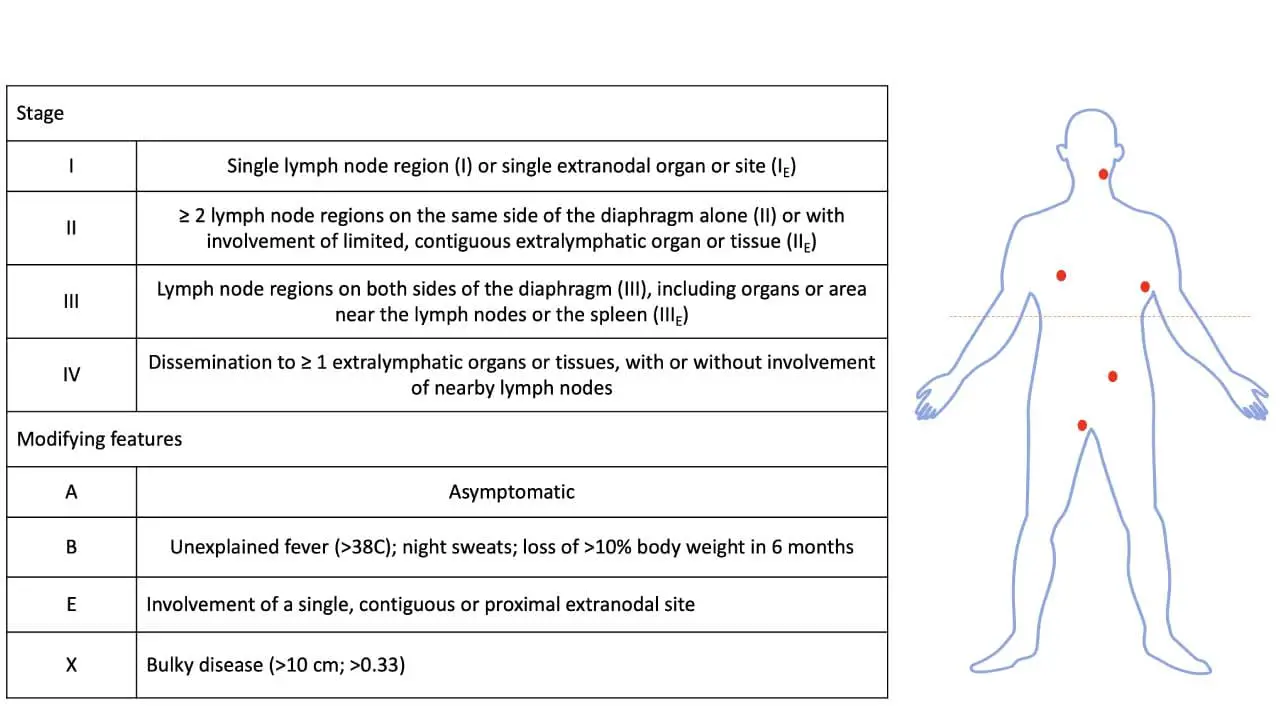

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, staging is performed to determine the extent of the disease. The standard staging system used for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the Ann Arbor Staging System, often with modifications.

- PET-CT Scan: A Positron Emission Tomography-Computed Tomography (PET-CT) scan is the most important staging tool. It combines metabolic imaging (PET) to identify areas of high glucose uptake (indicating active cancer cells) with anatomical imaging (CT) to pinpoint their location. This allows for a precise determination of the number and location of involved sites, including extranodal disease.

- Bone Marrow Biopsy: A biopsy of the bone marrow is performed to check for lymphoma involvement. This is often indicated for patients with unexplained cytopenias or when the PET-CT scan is negative, but suspicion of bone marrow involvement remains high.

- Lumbar Puncture: This procedure is performed to collect cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) to check for CNS involvement. It is typically reserved for patients at high risk of CNS disease, such as those with certain extranodal sites (e.g., testicular lymphoma) or specific molecular subtypes.

Staging and Prognosis

Accurate staging is vital to determine the extent of the disease and guide treatment. The Ann Arbor staging system is widely used, classifying the disease from Stage I (limited to one lymph node area) to Stage IV (widespread disease with involvement of extranodal sites).

To predict patient outcomes and guide clinical decisions, clinicians use prognostic indices. The most well-known is the International Prognostic Index (IPI).

The International Prognostic Index (IPI)

The International Prognostic Index is a widely used tool for risk stratification in patients with aggressive B-cell lymphomas like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). It is a simple scoring system that uses five key clinical factors to predict a patient’s outcome. One point is assigned for each of the following high-risk factors:

- Age > 60 years

- Elevated Serum LDH (above the upper limit of normal)

- ECOG Performance Status ≥ 2 (meaning the patient is unable to perform normal daily activities)

- Ann Arbor Stage III or IV

- Extranodal Sites > 1

The total score (0-5) correlates with the patient’s prognosis, particularly overall survival and progression-free survival. The scores are grouped into four risk categories:

- Low Risk: 0 or 1 factor

- Low-Intermediate Risk: 2 factors

- High-Intermediate Risk: 3 factors

- High Risk: 4 or 5 factors

The IPI is crucial for helping clinicians estimate prognosis, compare outcomes, and determine the appropriate intensity of treatment.

The IPI has been revised (R-IPI) in the modern era of rituximab-based therapy. It stratifies patients into three risk groups (very good, good, and poor), which better predict progression-free and overall survival in patients treated with the current standard of care.

Differential Diagnosis of Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL)

A definitive diagnosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) requires an excisional biopsy and histopathological analysis. However, given the non-specific nature of many of its signs and symptoms, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) must be distinguished from a variety of other diseases.

| Condition | Distinguishing Features |

| Other Lymphomas: Distinguishing DLBCL from other high-grade lymphomas can be challenging and often requires detailed immunohistochemistry and genetic testing. | |

| Burkitt Lymphoma | “Starry-sky” appearance on microscopy; characteristic gene translocation. |

| Follicular Lymphoma | Biopsy shows indolent follicular pattern with a high-grade large-cell component. |

| Primary Mediastinal B-cell Lymphoma | Presents as a bulky mass in the mediastinum; has unique molecular features. |

| Solid Tumors: DLBCL can mimic solid tumors, especially when it arises in an extranodal site. | |

| Undifferentiated Carcinomas | Immunohistochemical markers will be different from those of lymphoma. |

| Sarcomas | Tumors of mesenchymal origin; biopsy required for differentiation. |

| Melanomas | In rare cases, anaplastic melanoma can mimic DLBCL. |

| Infections: Infections can cause enlarged lymph nodes and systemic symptoms like fever and sweats, which can be confused with DLBCL. | |

| Infectious Mononucleosis | Caused by EBV; presents with fever and lymphadenopathy, especially in the neck. |

| Tuberculosis (TB) | Can cause lymphadenopathy, particularly in the neck. |

| Bacterial Infections | Generalized or localized bacterial infections can cause lymph node swelling. |

| Autoimmune Diseases: Certain autoimmune conditions, due to their association with chronic inflammation and lymphoproliferation, may mimic lymphoma. | |

| Sjögren’s Syndrome | Patients are at increased risk for DLBCL; new lymphadenopathy can signal transformation. |

| Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) | Lymphadenopathy is a common finding and can complicate diagnosis. |

Treatment and Management of Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL)

The goal of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) treatment is to cure the patient. The approach is highly personalized, taking into account the stage of the disease, the patient’s overall health, and specific prognostic factors like the IPI.

Standard of Care: R-CHOP Immunochemotherapy

The cornerstone of first-line therapy for the vast majority of DLBCL patients is the R-CHOP regimen. This is a combination of five agents administered every 21 days for a defined number of cycles (typically 6-8). The components of R-CHOP are:

- Rituximab: A monoclonal antibody that targets CD20, a protein found on the surface of both normal and malignant B-cells. Rituximab works by flagging these cells for destruction by the immune system.

- Cyclophosphamide: A potent chemotherapy agent that interferes with DNA replication.

- Hydroxydaunorubicin (Doxorubicin): An anthracycline chemotherapy drug that also damages DNA.

- Oncovin (Vincristine): A vinca alkaloid that inhibits cell division.

- Prednisone: A corticosteroid that has anti-inflammatory and anti-lymphoma effects.

Staging-Based Approach

- Limited-Stage Disease (Stage I/II): Patients with a low-risk IPI score are often treated with a reduced number of R-CHOP cycles (e.g., 3-4) followed by involved-field radiation therapy (IFRT) to the original site of disease. This approach aims to minimize the long-term side effects of chemotherapy while maintaining a high cure rate.

- Advanced-Stage Disease (Stage III/IV): These patients are treated with a full course of R-CHOP (e.g., 6 cycles). The addition of radiation is generally reserved for patients with a residual mass after chemotherapy.

Central Nervous System (CNS) Prophylaxis

For patients at high risk of the lymphoma spreading to the CNS (e.g., those with testicular lymphoma, involvement of multiple extranodal sites, or high IPI score), CNS prophylaxis is recommended. This is typically achieved with intrathecal methotrexate (injections into the spinal canal) or high-dose systemic methotrexate.

Supportive Care

Supportive care is a crucial part of management to help patients tolerate treatment. This includes:

- Antiemetics: To prevent nausea and vomiting.

- Growth Factor Support (G-CSF): To help the bone marrow recover and produce white blood cells after chemotherapy.

- Tumor Lysis Syndrome Prophylaxis: Using allopurinol or rasburicase to prevent kidney damage from rapid tumor breakdown.

Management of Relapsed or Refractory DLBCL

Despite the high cure rate with first-line therapy, a significant number of patients will experience disease relapse or have refractory disease (meaning the disease does not respond to initial treatment). The management of relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is complex and often involves more intensive strategies.

- Second-Line (Salvage) Chemotherapy The first step in treating relapsed or refractory disease is typically a course of salvage chemotherapy. The goal of this treatment is to reduce the tumor burden and achieve a partial or complete remission, which is necessary before proceeding to a more definitive therapy like a stem cell transplant. Commonly used regimens include:

- R-ICE: Rituximab, Ifosfamide, Carboplatin, and Etoposide

- R-DHAP: Rituximab, Dexamethasone, Cytarabine, and Cisplatin

- R-GDP: Rituximab, Gemcitabine, Dexamethasone, and Cisplatin

- High-Dose Chemotherapy and Autologous Stem Cell Transplant (ASCT) For younger, fit patients who are responsive to salvage chemotherapy, high-dose chemotherapy followed by an autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) is the standard of care for consolidating remission.

- Emerging and Novel Therapies For patients who are not candidates for or have failed salvage chemotherapy and ASCT, several novel therapies have become available and are transforming the treatment landscape.

- CAR T-cell Therapy (Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell Therapy): This is a groundbreaking immunotherapy where a patient’s own T-cells are collected, genetically engineered in a lab to recognize and attack lymphoma cells, and then reinfused. CAR T-cell therapy has shown remarkable success in patients with relapsed or refractory DLBCL and is considered a new standard of care in this setting.

- Bispecific Antibodies: These are a new class of antibodies that are designed to bring a patient’s own T-cells and lymphoma cells into close proximity. They have two binding sites—one that attaches to the T-cell and one that attaches to the cancer cell—effectively “bridging” them to facilitate the destruction of the tumor cell.

- Selinexor and Tafasitamab: These are other targeted agents that are approved for use in certain settings of relapsed/refractory DLBCL.

- Polatuzumab Vedotin: This is an antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) that targets the CD79b protein on the surface of B-cells. By attaching a potent chemotherapy agent (vedotin) to a targeted antibody, it delivers the drug directly to the lymphoma cells, minimizing damage to healthy tissues. It is approved for use in combination with bendamustine and rituximab (Pola-BR) for patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

Glossary of Medical Terms

- Biopsy: The removal of a small piece of tissue for laboratory examination.

- B-cell: A type of white blood cell that produces antibodies.

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC): A laboratory technique that uses antibodies to detect specific proteins (e.g., CD20, BCL2) in tissue samples, helping to classify the type of lymphoma.

- Lymphoma: A cancer that begins in the lymphocytes of the immune system.

- Monoclonal Antibody: A laboratory-produced antibody that mimics the body’s natural antibodies to target specific cells.

- Relapsed/Refractory (R/R): When a cancer returns after treatment (relapsed) or does not respond to treatment (refractory).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the difference between Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma?

The main difference is the type of malignant cell. Hodgkin lymphoma is characterized by the presence of Reed-Sternberg cells, while non-Hodgkin lymphomas (like DLBCL) are not. The diseases also differ in their pattern of spread and treatment approaches.

Can DLBCL be cured?

Yes, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is considered a curable cancer. The majority of patients achieve long-term remission with standard first-line therapy.

What is the role of a physical therapist in DLBCL care?

A physical therapist can help patients manage fatigue, a common side effect of chemotherapy, and improve their strength and mobility during and after treatment.

Are there any specific diet recommendations for DLBCL patients?

While there is no specific “anti-cancer” diet, maintaining a balanced diet with proper hydration is crucial to support the body during chemotherapy and manage side effects like nausea or mouth sores.

What is the life expectancy of someone with DLBCL?

According to recent data, the overall 5-year survival rate for people with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is between 60% and 70%. This rate has improved dramatically over the past few decades with the introduction of new therapies.

The specific survival rate for an individual is influenced by several factors, including:

- Age: Younger patients generally have a better prognosis.

- Stage of the Disease: Early-stage DLBCL (stage I or II) has a better prognosis than advanced-stage DLBCL (stage III or IV).

- Overall Health: A person’s general health, or “performance status,” and the presence of other medical conditions can impact how they tolerate and respond to treatment.

- Extranodal Disease: Whether the cancer has spread outside of the lymph nodes to other organs.

- Response to Treatment: The most important factor is how well the cancer responds to the initial treatment regimen.

How quickly does DLBCL grow?

Unlike some other types of lymphoma that can grow slowly over many years, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) often presents with symptoms that appear and worsen quickly. Symptoms like an enlarged lymph node or a rapidly growing mass, along with fever, night sweats, and unexplained weight loss, can develop and progress over a period of just a few weeks or months. This rapid progression is why a prompt diagnosis and immediate treatment are crucial for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

Can DLBCL spread to the brain?

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is an aggressive type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that can affect any part of the body. While it most often starts in the lymph nodes, it can sometimes spread to other areas, including the central nervous system, which consists of the brain and spinal cord.

Is DLBCL inherited?

DLBCL is not considered a hereditary or inherited disease. While the cancer is caused by genetic changes, those changes are almost always acquired during a person’s lifetime, rather than being passed down from their parents.

What happens if DLBCL is left untreated?

Left untreated, Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) is a very aggressive and life-threatening cancer. Because it grows and spreads rapidly, the prognosis is very poor, and without treatment, it is typically fatal within a few months to a year.

What are the secondary cancers after DLBCL?

Surviving diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) unfortunately comes with an increased risk of developing a second primary malignancy (SPM), which are new and unrelated cancers.

The types of secondary cancers can be divided into two main categories: solid tumors and other hematologic malignancies. The most common solid tumors include cancers of the lung, breast, bladder, thyroid, and gastrointestinal system (such as the stomach and colon), as well as melanoma. The risk for solid tumors tends to increase over time, particularly more than 10 years after treatment.

Additionally, survivors have a higher risk of developing other blood cancers, most notably acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS). The increased risk is largely attributed to the effects of the chemotherapy and radiation therapy used to treat the initial diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Padala SA, Kallam A. Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. [Updated 2023 Apr 24]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557796/

- Shi, Y., Xu, Y., Shen, H., Jin, J., Tong, H., & Xie, W. (2024). Advances in biology, diagnosis and treatment of DLBCL. Annals of hematology, 103(9), 3315–3334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-024-05880-z

- Tilly, H., Gomes da Silva, M., Vitolo, U., Jack, A., Meignan, M., Lopez-Guillermo, A., Walewski, J., André, M., Johnson, P. W., Pfreundschuh, M., Ladetto, M., & ESMO Guidelines Committee (2015). Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL): ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology, 26 Suppl 5, v116–v125. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdv304

- Nowakowski, G. S., & Czuczman, M. S. (2015). ABC, GCB, and Double-Hit Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: Does Subtype Make a Difference in Therapy Selection?. American Society of Clinical Oncology educational book. American Society of Clinical Oncology. Annual Meeting, e449–e457. https://doi.org/10.14694/EdBook_AM.2015.35.e449

- Liang, X. J., Song, X. Y., Wu, J. L., Liu, D., Lin, B. Y., Zhou, H. S., & Wang, L. (2022). Advances in Multi-Omics Study of Prognostic Biomarkers of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. International journal of biological sciences, 18(4), 1313–1327. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.67892

- Kanas, G., Ge, W., Quek, R. G. W., Keeven, K., Nersesyan, K., & Jon E Arnason (2022). Epidemiology of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and follicular lymphoma (FL) in the United States and Western Europe: population-level projections for 2020-2025. Leukemia & lymphoma, 63(1), 54–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428194.2021.1975188

- Rojek, A. E., & Smith, S. M. (2022). Evolution of therapy for limited stage diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood cancer journal, 12(2), 33. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-021-00596-z

- Harkins, R. A., Chang, A., Patel, S. P., Lee, M. J., Goldstein, J. S., Merdan, S., Flowers, C. R., & Koff, J. L. (2019). Remaining challenges in predicting patient outcomes for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Expert review of hematology, 12(11), 959–973. https://doi.org/10.1080/17474086.2019.1660159

- Shi, Y., Xu, Y., Shen, H., Jin, J., Tong, H., & Xie, W. (2024). Advances in biology, diagnosis and treatment of DLBCL. Annals of hematology, 103(9), 3315–3334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-024-05880-z