TL;DR

Hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) is a rare group of disorders characterized by persistently high blood eosinophils (≥1,500/μL), leading to inflammation and organ damage.

- Pathophysiology ▾: Caused by eosinophil overproduction and toxic granule release, resulting in tissue infiltration, inflammation, and fibrosis in organs like the heart and lungs.

- Causes ▾: Classified into Primary (clonal/neoplastic), Secondary (reactive to another condition), and Idiopathic (unknown cause) types.

- Symptoms ▾: Diverse symptoms depend on organ involvement, including fatigue, skin rashes, respiratory issues, and life-threatening cardiac problems.

- Diagnosis ▾: Involves blood tests for persistent hypereosinophilia, ruling out other causes, and assessing organ damage through imaging and biopsies. Genetic testing is crucial for classification.

- Treatment ▾: Aims to lower eosinophil counts and prevent organ damage. Includes corticosteroids, targeted therapies like imatinib for specific genetic mutations, and biologics like mepolizumab.

- Prognosis ▾: Has improved significantly with modern therapies. Early diagnosis before irreversible organ damage is the most critical factor for a favorable outcome.

*Click ▾ for more information

What is Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES)?

Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) is a group of rare disorders characterized by persistent hypereosinophilia and associated damage to multiple organs. The clinical diagnosis and management of hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) can be challenging due to its diverse presentations and the need to rule out other potential causes of eosinophilia.

Eosinophilia vs Hypereosinophilia

Eosinophilia

Eosinophilia is the condition of having an abnormally high number of eosinophils in the blood. Eosinophils are a type of white blood cell that play a role in the immune system, particularly in allergic reactions and fighting parasitic infections.

- Quantitative Definition: A diagnosis of eosinophilia is typically made when the absolute eosinophil count (AEC) in the blood is greater than 500 cells per microliter (μL).

- Significance: Eosinophilia is a common finding and is often a reactive response to another underlying condition. It can be a temporary state and doesn’t necessarily indicate a severe or chronic disease.

- Common Causes: The most frequent causes of eosinophilia are:

- Allergic diseases (e.g., asthma, hay fever, eczema)

- Parasitic infections

- Drug reactions

- Some inflammatory and autoimmune disorders

Hypereosinophilia

Hypereosinophilia is a more severe and prolonged condition of elevated eosinophils. It represents a higher threshold of the eosinophil count and is a more serious finding than simple eosinophilia.

- Quantitative Definition: Hypereosinophilia is defined by a persistently elevated absolute eosinophil count (AEC) of greater than 1,500 cells per microliter (μL). The count must be elevated on two or more occasions, usually at least one month apart.

- Significance: A diagnosis of hypereosinophilia prompts a more extensive medical investigation to find the cause and to check for signs of organ damage, as seen in Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES). While it can still be a secondary response to a severe underlying condition, it is a key diagnostic criterion for Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) and other eosinophilic disorders.

Importance of Recognizing Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES)

Recognizing and promptly diagnosing Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) is critical for clinicians due to several key factors:

- Preventing Irreversible Organ Damage: The most significant danger of Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) is the potential for eosinophils to infiltrate and damage vital organs, particularly the heart. This can lead to a condition called endomyocardial fibrosis, which can cause heart failure and is a major cause of death in Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) patients. Early diagnosis and treatment are essential to prevent this irreversible damage.

- Broad and Vague Symptoms: Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) presents with a wide range of nonspecific symptoms (e.g., fatigue, cough, skin rashes) that can mimic many other, more common conditions. This makes it a diagnostic challenge. Clinicians must consider HES in patients with persistent eosinophilia that cannot be explained by other causes.

- Specific, Targeted Therapies: HES is a heterogeneous group of disorders. Some subtypes, particularly those with specific genetic mutations like the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion gene, respond exceptionally well to targeted therapies like tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Identifying these specific subtypes is important for providing the most effective treatment and improving a patient’s prognosis.

- Exclusion of Other Serious Conditions: The diagnosis of Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) is one of exclusion. This means clinicians must first rule out other potential causes of hypereosinophilia, such as parasitic infections, certain cancers (like lymphomas and leukemias), and autoimmune diseases. This systematic diagnostic process is vital to ensure the patient receives the correct treatment for their underlying condition.

Function of Eosinophils

- Defense Against Parasites: This is their most well-known role. Eosinophils are particularly effective against large, multicellular parasites like helminths (worms) that are too big for other immune cells to engulf. They release a host of toxic proteins from their granules, such as major basic protein (MBP) and eosinophil cationic protein (ECP), which are highly damaging to these invaders.

- Allergic Reactions and Asthma: Eosinophils are central players in the inflammation associated with allergies and asthma. When an allergen is present, they are recruited to the site of inflammation (e.g., the airways in asthma) and release their granule contents. While this is part of the immune response, the toxic proteins and other mediators can also cause significant tissue damage, leading to symptoms like swelling, airway narrowing, and bronchospasm.

- Immune Modulation: Beyond their direct effector functions, eosinophils also act as regulators of the immune response. They can release cytokines and chemokines that influence other immune cells, including T cells and B cells. They have even been shown to act as antigen-presenting cells, a role more famously played by dendritic cells, which you’ve mentioned before. This regulatory function highlights their role in orchestrating a balanced immune response.

- Tissue Homeostasis and Repair: Emerging research indicates that eosinophils have a role in maintaining tissue health and promoting repair. They are found in many healthy tissues, such as the gut and adipose tissue, where they contribute to a balanced inflammatory environment and help with wound healing and tissue remodeling.

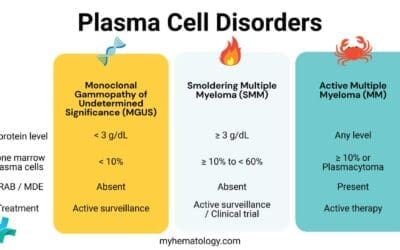

Classification of Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES)

Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) is broadly classified into three main categories, based on the etiology of hypereosinophilia.

Primary (or Neoplastic) HES

This form is caused by an underlying clonal or cancerous condition originating in the blood-forming cells of the bone marrow. The eosinophils themselves are part of a neoplastic process. This category includes:

- Myeloproliferative Variant (M-HES): This is characterized by the uncontrolled proliferation of eosinophils and other blood cells, often due to a specific genetic mutation. A key example is the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion gene, which is highly significant because it makes the condition responsive to a specific targeted therapy called imatinib. This variant is often associated with elevated serum vitamin B12 and tryptase levels.

- Lymphocytic Variant (L-HES): In this case, the hypereosinophilia is driven by a population of aberrant T-lymphocytes. These T cells produce excessive amounts of cytokines, particularly interleukin-5 (IL-5), which stimulates the overproduction of eosinophils. L-HES often presents with prominent skin manifestations.

Secondary (or Reactive) HES

In this type, the hypereosinophilia is a reactive response to another underlying condition, and the eosinophils themselves are not clonal or cancerous. The high eosinophil count is a symptom of another disease. Causes can include:

- Parasitic infections (e.g., helminths)

- Allergic diseases

- Autoimmune or inflammatory disorders

- Certain non-hematologic cancers

Idiopathic HES (IHES)

This is a diagnosis of exclusion. It is used for cases where a patient meets all the diagnostic criteria for HES (persistent hypereosinophilia and organ damage) but a comprehensive evaluation fails to identify a primary neoplastic cause (like a genetic mutation) or a secondary reactive cause. As diagnostic technology has improved, a growing number of cases that were once classified as idiopathic are now being reclassified as a primary or secondary form.

Pathophysiology of HES

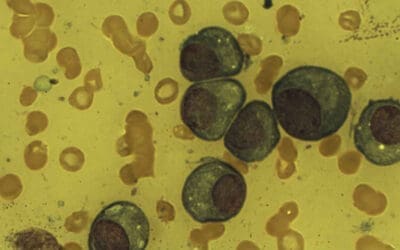

The pathophysiology of HES centers on the overproduction and dysregulated activation of eosinophils, which then leads to their infiltration into tissues and subsequent organ damage.

In HES, there is a persistent and excessive production of eosinophils, often driven by certain cytokines. The most important cytokine for eosinophil growth and differentiation is Interleukin-5 (IL-5). Other cytokines, like IL-3 and GM-CSF, also play a role.

The activated eosinophils migrate from the bloodstream into various tissues and organs. This infiltration is what leads to the wide range of clinical symptoms. The eosinophils release their stored granule proteins, which are highly toxic.

Eosinophils contain a cocktail of potent, pre-formed substances, including:

- Major Basic Protein (MBP): This protein is a strong toxin that damages the membranes of target cells, including those of parasites and human tissue.

- Eosinophil Cationic Protein (ECP): ECP is another cytotoxic protein that can cause direct damage to cells.

- Eosinophil Peroxidase (EPO): This enzyme generates reactive oxygen species, contributing to oxidative stress and tissue damage.

- Other Cytokines and Lipid Mediators: Eosinophils also release various cytokines and pro-inflammatory molecules that perpetuate the inflammatory response and recruit more immune cells to the site.

The continuous release of these toxic substances causes chronic inflammation and, over time, leads to tissue damage and fibrosis (scarring). This fibrotic process is particularly dangerous in the heart, where it can lead to endomyocardial fibrosis, resulting in heart failure.

Causes of HES

The underlying causes are what differentiate the subtypes of Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES).

Primary (Neoplastic) HES

This form is caused by an intrinsic problem in the hematopoietic (blood-forming) stem cells. The eosinophils are part of a clonal, or cancerous, population.

A key cause in this category is the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion gene. This mutation creates a constitutively active tyrosine kinase, a protein that drives the uncontrolled proliferation of eosinophils. This specific mutation is crucial to identify because it makes the disease highly responsive to tyrosine kinase inhibitor drugs like imatinib. Other, less common gene rearrangements involving PDGFRB or FGFR1 also fall into this category.

Secondary (Reactive) HES

The high eosinophil count is a reaction to another non-hematologic disease.

- Lymphocytic Variant (L-HES): This is the most common cause of secondary Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES). It is driven by an abnormal population of T-lymphocytes. These T cells are not cancerous but are “aberrant,” meaning they overproduce cytokines, especially Interleukin-5 (IL-5). This flood of IL-5 then excessively stimulates the bone marrow to produce eosinophils, leading to the syndrome. This mechanism, where a T-cell-driven cytokine cascade leads to eosinophilia, is similar in concept to how other antigen-presenting cells like dendritic cells can activate T cells to mount an immune response.

- Other Causes: A wide variety of other conditions can cause secondary hypereosinophilia, including:

- Severe parasitic infections (e.g., filariasis)

- Certain autoimmune diseases and vasculitides (e.g., eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis)

- Some non-hematologic malignancies

- Severe allergic or drug reactions

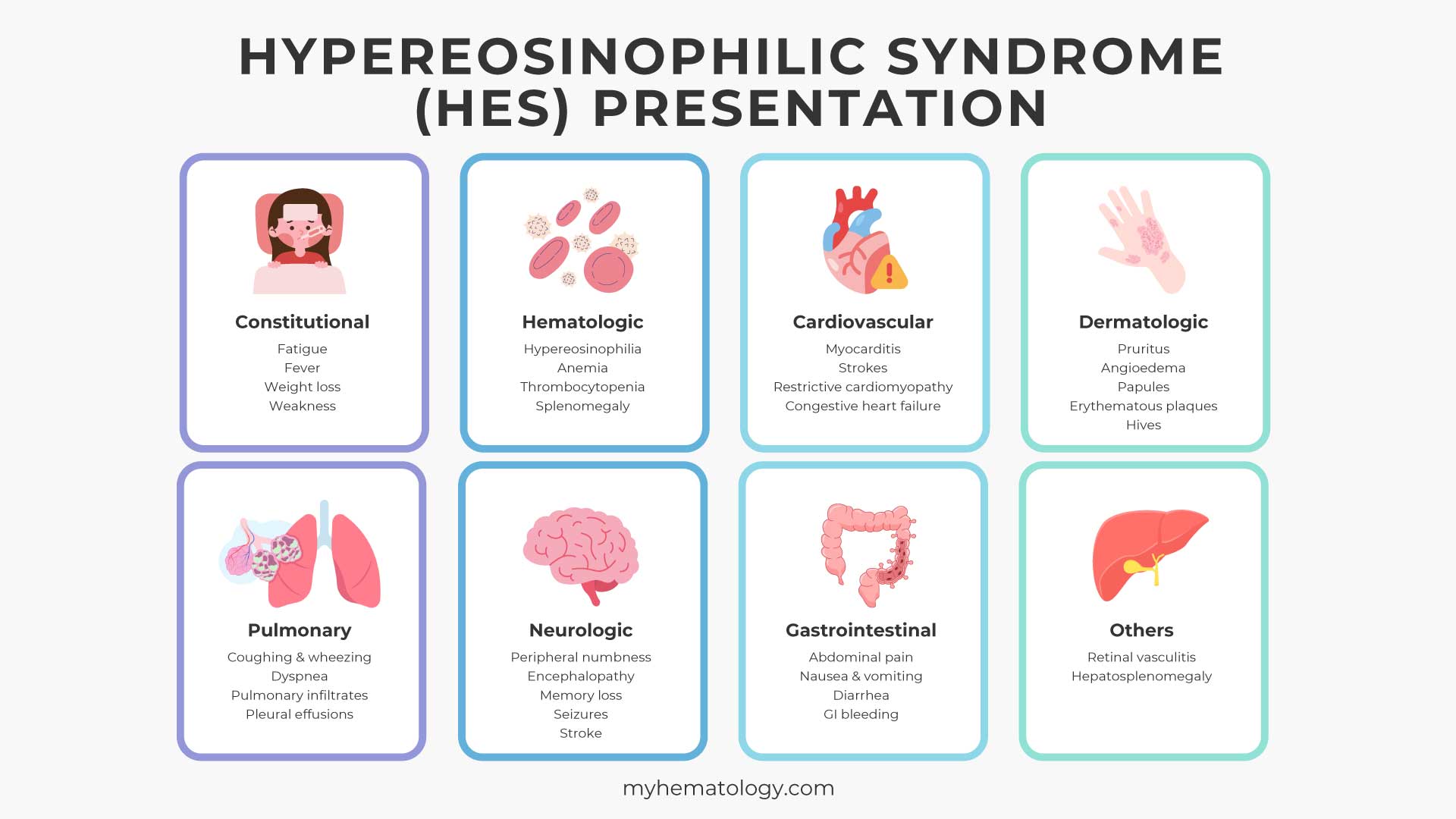

Clinical Manifestations (Symptoms and Organ Involvement)

The clinical manifestations of Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) are highly variable and depend on which organs are affected by the infiltrating eosinophils. Because eosinophils can accumulate in virtually any tissue, the disease can present with a wide range of symptoms, making diagnosis a significant challenge.

Constitutional Symptoms

These are general, non-specific symptoms that can occur in many diseases and are present in a significant number of HES patients:

- Fatigue

- Fever

- Weight loss

- Weakness

Hematologic Manifestations

- Hypereosinophilia: The defining feature of HES, with an absolute eosinophil count (AEC) of >1,500 cells/μL persisting for at least six months.

- Anemia or Thrombocytopenia: Lower than normal red blood cell or platelet counts can sometimes occur, especially in the myeloproliferative variant of HES.

- Splenomegaly: Enlargement of the spleen is common, particularly in the myeloproliferative variant.

Cardiovascular Manifestations (Most Dangerous)

Cardiac involvement is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in HES. The damage occurs in three stages:

- Acute Necrotic Stage: Eosinophils infiltrate the heart muscle (myocardium) and release their toxic contents, causing inflammation and cell death. This can lead to myocarditis and heart failure symptoms.

- Thrombotic Stage: The damaged heart muscle forms blood clots (thrombi) on the inner walls of the ventricles. These clots can break off and travel to other parts of the body, causing strokes or embolisms in other organs.

- Fibrotic Stage: Over time, the damaged heart tissue is replaced by scar tissue (fibrosis). This leads to endomyocardial fibrosis, a condition where the inner lining of the heart and the valve structures are thickened and hardened, severely impairing the heart’s function and leading to restrictive cardiomyopathy and congestive heart failure.

Dermatologic (Skin) Manifestations

Skin problems are among the most common signs of HES, often affecting more than 50% of patients. They can include:

- Pruritus (itching): A very common and often severe symptom.

- Angioedema: Swelling, often of the face, lips, and extremities.

- Papules and Nodules: Small, solid bumps under the skin.

- Erythematous plaques: Red, raised patches of skin.

- Hives (urticaria): Welts on the skin.

Pulmonary (Lung) Manifestations

Lung involvement is also frequent and can present as:

- Cough and wheezing: Similar to asthma, but often unresponsive to standard asthma treatments.

- Dyspnea (shortness of breath): Caused by inflammation and damage to the lung tissue.

- Pulmonary infiltrates: Areas of inflammation visible on a chest X-ray or CT scan.

- Pleural effusions: Fluid accumulation around the lungs.

Neurologic Manifestations

Neurological symptoms can be a direct result of eosinophil infiltration into the brain and nerves or from embolic events (blood clots traveling to the brain).

- Peripheral Neuropathy: Nerve damage in the extremities, causing numbness, tingling, or weakness.

- Central Nervous System (CNS) Issues: Encephalopathy (brain dysfunction), memory loss, behavioral changes, confusion, or even seizures.

- Stroke: Caused by a thromboembolism from the heart.

Gastrointestinal Manifestations

Eosinophilic infiltration of the gastrointestinal tract can lead to:

- Abdominal pain

- Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea

- Gastrointestinal bleeding

Other Manifestations

- Ocular (Eye) Involvement: Visual disturbances or redness due to retinal vasculitis.

- Hepatosplenomegaly: Enlarged liver and spleen.

Due to this wide array of possible symptoms, a clinician’s suspicion of Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) is important when evaluating a patient with unexplained, persistent hypereosinophilia and evidence of multi-organ involvement. A thorough diagnostic workup is necessary to rule out other causes and to confirm the diagnosis.

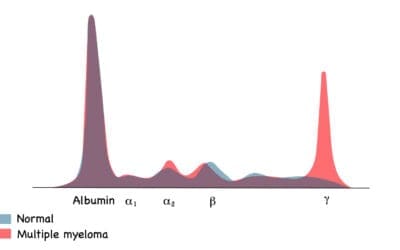

Laboratory Investigations and Diagnosis

The laboratory diagnosis of Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) is a multi-step process that involves a combination of blood tests, genetic and molecular studies, and other diagnostic procedures to confirm the presence of the syndrome and, most importantly, to determine its underlying cause. The primary goal is to distinguish Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) from other, more common causes of eosinophilia.

Complete Blood Count

- Absolute Eosinophil Count (AEC): This is the foundational test. A diagnosis of Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) requires a persistent AEC of greater than 1,500 cells per microliter (μL). This high count should be confirmed on at least two separate occasions, usually at least one month apart, to rule out a temporary, reactive cause.

- Other CBC Findings: Other abnormalities on the CBC, such as anemia (low red blood cells) or thrombocytopenia (low platelets), may suggest a myeloproliferative variant of HES.

Exclusion of Secondary Causes of Eosinophilia

Before a diagnosis of Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) can be made, a comprehensive workup is necessary to rule out other conditions that can cause eosinophilia. Tests may include:

- Stool Examination: To check for parasitic infections, particularly helminths (worms), which are a common cause of eosinophilia.

- Allergy Testing: Skin prick tests or blood tests (e.g., for IgE levels) to rule out allergic conditions like asthma or drug hypersensitivity reactions.

- Infectious Disease Serology: To test for various infections that can cause a high eosinophil count.

- Autoimmune Markers: To screen for autoimmune and inflammatory disorders that may present with eosinophilia.

Molecular and Genetic Testing

This is a critical step to classify the Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) subtype, as it directly impacts treatment.

- FIP1L1-PDGFRA Fusion Gene: This is the most important genetic test in the workup for Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES). The FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion gene is a chromosomal deletion that creates an abnormal tyrosine kinase, which drives the overproduction of eosinophils.

Its presence confirms a myeloproliferative variant and indicates that the patient will likely respond well to targeted therapy with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor like imatinib. This test is typically performed using techniques like FISH (Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization) or PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) on peripheral blood or bone marrow samples.

- T-cell Receptor Rearrangement: If a patient has signs of the lymphocytic variant of HES, such as prominent skin manifestations, a T-cell receptor gene rearrangement study may be performed. The presence of a clonal T-cell population that overproduces IL-5 can confirm this subtype.

- Other Gene Mutations: Tests for other, less common gene rearrangements (PDGFRB, FGFR1) and other mutations (JAK2) may also be performed, depending on the clinical suspicion.

Bone Marrow Examination

- Morphology: The biopsy can reveal an increase in eosinophils and their precursors. It may also show signs of other myeloid abnormalities or fibrosis, which can further support a diagnosis of a myeloproliferative neoplasm.

- Special Stains: Immunohistochemical stains on the biopsy sample can help to identify other cell types, like an increased number of mast cells, which can be seen in some Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) variants.

- Cytogenetic Analysis: This helps to identify chromosomal abnormalities that may point to an underlying clonal disorder.

Assessment of Organ Damage

As Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) is defined by both hypereosinophilia and organ damage, various laboratory and imaging tests are used to evaluate for end-organ involvement.

- Cardiac Evaluation: This is of paramount importance. An echocardiogram is used to assess heart function and look for signs of endomyocardial fibrosis or valvular dysfunction. Blood tests for cardiac biomarkers like troponin may also be elevated.

- Pulmonary Function Tests: To assess lung function and look for signs of obstructive or restrictive lung disease.

- Imaging: CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis can reveal pulmonary infiltrates, pleural effusions, hepatosplenomegaly, or lymphadenopathy.

- Tissue Biopsy: If a specific organ is affected (e.g., skin, lung), a biopsy may be performed to confirm the presence of eosinophilic infiltration and tissue damage.

Criteria for diagnosis of Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES)

The modern criteria for Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) diagnosis, as defined by expert groups like the International Cooperative Working Group on Eosinophil Disorders (ICOG-EO), are a combination of three key components.

- Hypereosinophilia: This is the foundational criterion. The patient must have an absolute eosinophil count (AEC) of greater than 1,500 cells per microliter (μL) in the peripheral blood. This high count must be persistent, observed on at least two occasions.

- Evidence of Organ Damage: The hypereosinophilia must be associated with signs or symptoms of organ damage or dysfunction that are attributable to the eosinophils. Evidence of organ damage is assessed through various clinical, laboratory, and imaging studies, such as:

- An echocardiogram showing signs of endomyocardial fibrosis.

- A skin, lung, or other tissue biopsy showing extensive eosinophilic infiltration.

- Abnormal liver or kidney function tests.

- Pulmonary function tests indicating lung damage.

- Neurological symptoms like peripheral neuropathy or confusion.

- Exclusion of Other Causes: All other potential causes of the hypereosinophilia must be ruled out.

- Parasitic infections (e.g., helminths).

- Allergic diseases (e.g., severe asthma, drug reactions).

- Other hematologic malignancies (e.g., chronic myeloid leukemia).

- Autoimmune and inflammatory disorders (e.g., Churg-Strauss syndrome).

Treatment and Management of Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES)

The treatment and management of Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) are highly personalized and depend critically on the underlying cause (the specific HES subtype) and the severity of organ damage. The main goals of treatment are to reduce the number of eosinophils in the blood and tissues, prevent further organ damage, and alleviate symptoms.

General Principles of Management

- Prompt Treatment for Organ Damage: The presence of significant organ damage, especially to the heart, lungs, or nervous system, necessitates immediate and aggressive treatment, even before a definitive Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) subtype is identified.

- Steroids as First-Line Therapy: Corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone) are typically the first-line treatment for most Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) patients. They work quickly and effectively to reduce eosinophil counts and inflammation. The dose is often tapered once the eosinophil count is controlled to minimize long-term side effects.

- Targeted Therapies for Specific Subtypes: The discovery of specific genetic mutations and underlying drivers has revolutionized Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) treatment.

- Supportive Care: This includes treating the specific symptoms and complications of Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES), such as using blood thinners (anticoagulants) to prevent blood clots in patients with cardiac involvement.

Treatment by Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) Subtype

Myeloproliferative Variant (M-HES)

This variant is defined by an underlying clonal proliferation of eosinophils, often due to a specific genetic mutation.

- Imatinib (Gleevec): This is the gold-standard treatment for M-HES patients who test positive for the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion gene. Imatinib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that specifically blocks the abnormal protein produced by this gene. The response to imatinib is often dramatic and rapid, with eosinophil counts normalizing within days or weeks. This is a classic example of targeted therapy.

- Hydroxyurea: For M-HES patients who do not have a treatable fusion gene or who do not respond to imatinib, hydroxyurea, a chemotherapeutic agent, may be used. It works by suppressing bone marrow production of blood cells, including eosinophils.

- Other Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors: For patients with other rare gene rearrangements (e.g., involving PDGFRB or FGFR1), other targeted kinase inhibitors may be used.

Lymphocytic Variant (L-HES)

This variant is caused by an aberrant T-cell population that overproduces IL-5, a key cytokine for eosinophil growth.

- Corticosteroids: These are the primary treatment for L-HES and are generally effective at controlling eosinophil counts.

- Interferon-alpha: This is often a second-line therapy for patients who are unresponsive to or intolerant of corticosteroids. It works by modulating the immune system to reduce eosinophil production.

- Targeted Biologics: The discovery of the central role of IL-5 in this subtype has led to the development of targeted therapies. Mepolizumab (Nucala), a monoclonal antibody that specifically targets and neutralizes IL-5, is now approved for the treatment of HES. Other anti-IL-5 or anti-IL-5 receptor antibodies are also being investigated.

Idiopathic HES (IHES)

This is a diagnosis of exclusion, used for patients who meet the HES criteria but have no identifiable primary or secondary cause.

- Corticosteroids: Like L-HES, this is the first-line treatment. The goal is to find the lowest effective dose that controls symptoms and prevents organ damage.

- Alternative Agents: For steroid-resistant or steroid-dependent patients, other treatments are considered. These can include:

- Hydroxyurea: To suppress eosinophil production.

- Interferon-alpha: An immunomodulatory agent.

- Mepolizumab: The anti-IL-5 monoclonal antibody is also approved for IHES and is a valuable option for patients who do not respond to or cannot tolerate steroids.

- Other Immunosuppressants: Agents like cyclosporine or methotrexate may be used in rare cases.

Management of Severe or Life-Threatening Manifestations

- High-Dose IV Corticosteroids: In cases of severe, acute Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) with rapidly progressing organ damage (e.g., severe heart or neurological involvement), high-dose intravenous corticosteroids are administered immediately to rapidly lower the eosinophil count and halt the inflammatory process.

- Emergency Measures: For patients with a very high eosinophil count that poses a risk of hyperviscosity (thickened blood), treatments like leukapheresis (a procedure to remove white blood cells from the blood) may be used as a temporary measure.

- Cardiac Monitoring: Given the high risk of heart damage, all Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) patients should undergo regular cardiac evaluation, including echocardiograms, to monitor for signs of endomyocardial fibrosis.

Prognosis of HES

The prognosis of Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) has significantly improved over the last few decades, largely due to better diagnostic tools and the development of targeted therapies. In the past, the outlook was often grim, with a high mortality rate primarily due to irreversible heart damage. Today, the prognosis is much more favorable, but it still varies greatly depending on several factors.

Key Factors Influencing Prognosis

- Presence and Severity of Organ Damage: This is the most important factor. Cardiac involvement is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES). If heart damage, such as endomyocardial fibrosis, is present at the time of diagnosis, the prognosis is generally worse. Early diagnosis, before irreversible organ damage has occurred, is the single most important determinant of a good outcome.

- HES Subtype: The specific cause of the Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) significantly influences the prognosis because it dictates the treatment options.

- Myeloproliferative Variant (M-HES) with the FIP1L1-PDGFRA Fusion Gene: The prognosis for this specific subtype has been completely transformed by the introduction of imatinib, a targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Most patients with this mutation have a near-normal life expectancy with proper treatment, as the drug can induce a complete and durable remission.

- Lymphocytic Variant (L-HES): Patients with this subtype generally have a good prognosis as they often respond well to corticosteroids and other immunomodulatory therapies, including anti-IL-5 biologics like mepolizumab.

- Idiopathic HES (IHES): The prognosis for this group can be more variable, as the underlying cause is not known. However, many patients respond well to corticosteroids or other agents like mepolizumab, leading to long-term control of the disease.

- Response to Treatment: A patient’s response to therapy is a major predictor of their outcome. For the imatinib-responsive subtype, a rapid and complete response leads to a very favorable prognosis. For other subtypes, achieving and maintaining remission (low eosinophil counts and no evidence of new organ damage) on the lowest effective dose of medication is the goal.

Historical Context and Modern Outlook

Before the 1980s, the median survival for Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) patients was often only a few years, with a five-year survival rate as low as 12% in some studies from the 1970s.

With modern diagnostic techniques and effective treatments like imatinib and mepolizumab, the five-year survival rate for HES patients is now reported to be over 80%. Many patients with HES can live a normal or near-normal lifespan, especially if their disease is well-controlled and organ damage is minimal.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Is hypereosinophilic syndrome a rare disease?

Yes, Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) is considered a rare disease. Estimates for the prevalence of HES range from approximately 0.36 to 6.3 cases per 100,000 people.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Caminati, M., Brussino, L., Carlucci, M., Carlucci, P., Carpagnano, L. F., Caruso, C., Cosmi, L., D’Amore, S., Del Giacco, S., Detoraki, A., Di Gioacchino, M., Matucci, A., Mormile, I., Granata, F., Guarnieri, G., Krampera, M., Maule, M., Nettis, E., Nicola, S., … de Paulis, A. (2024). Managing Patients with Hypereosinophilic Syndrome: A Statement from the Italian Society of Allergy, Asthma, and Clinical Immunology (SIAAIC). Cells, 13(14), 1180. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13141180

- Klion A. (2018). Hypereosinophilic syndrome: approach to treatment in the era of precision medicine. Hematology. American Society of Hematology. Education Program, 2018(1), 326–331. https://doi.org/10.1182/asheducation-2018.1.326

- Roufosse, F.E., Goldman, M. & Cogan, E. Hypereosinophilic syndromes. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2, 37 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-2-37

- Curtis, C., & Ogbogu, P. (2016). Hypereosinophilic Syndrome. Clinical reviews in allergy & immunology, 50(2), 240–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-015-8506-7

- Mikhail ES, Ghatol A. Hypereosinophilic Syndrome. [Updated 2024 Jan 11]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK599558/