TL;DR

Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction (AHTR) is an acute hemolysis due to the administration of antigenically incompatible red cells.

- Timing ▾: During transfusion or within 24 hours.

- Signs and Symptoms ▾:

- Fever and chills

- Back or flank pain

- Hemoglobinuria

- Hypotension and shortness of breath

- Severe cases can lead to shock, DIC and renal failure

- Causes or mechanism ▾: Usually due to clerical error causing ABO incompatibility. The presence of preformed antibodies in the body against transfused blood causing intravascular hemolysis.

- Treatment and management ▾:

- STOP infusion

- Identity of patient and unit must be reconfirmed

- Serologic testing repeated on donor blood and post-transfusion samples of patient’s blood

- Maintain IV access

- Monitor blood pressure and urine output

*Click ▾ for more information

What is an Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction (AHTR)?

An Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction (AHTR) is a severe adverse transfusion reaction that occurs during or within 24 hours of a blood transfusion. It is caused by the destruction of red blood cells in the recipient’s blood by antibodies in the donor blood. Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction (AHTR) can be fatal.

What are the symptoms of Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction (AHTR)?

Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction (AHTR) symptoms can vary depending on the severity of the reaction. Mild Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction (AHTR) may cause only a few symptoms, such as fever and chills. Severe Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction (AHTR) can cause a variety of symptoms, including:

- Fever

- Chills

- Hives

- Itching

- Shortness of breath

- Chest pain

- Nausea and vomiting

- Low blood pressure

- Back pain

- Hemoglobinuria (red urine)

- Jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes)

- Shock

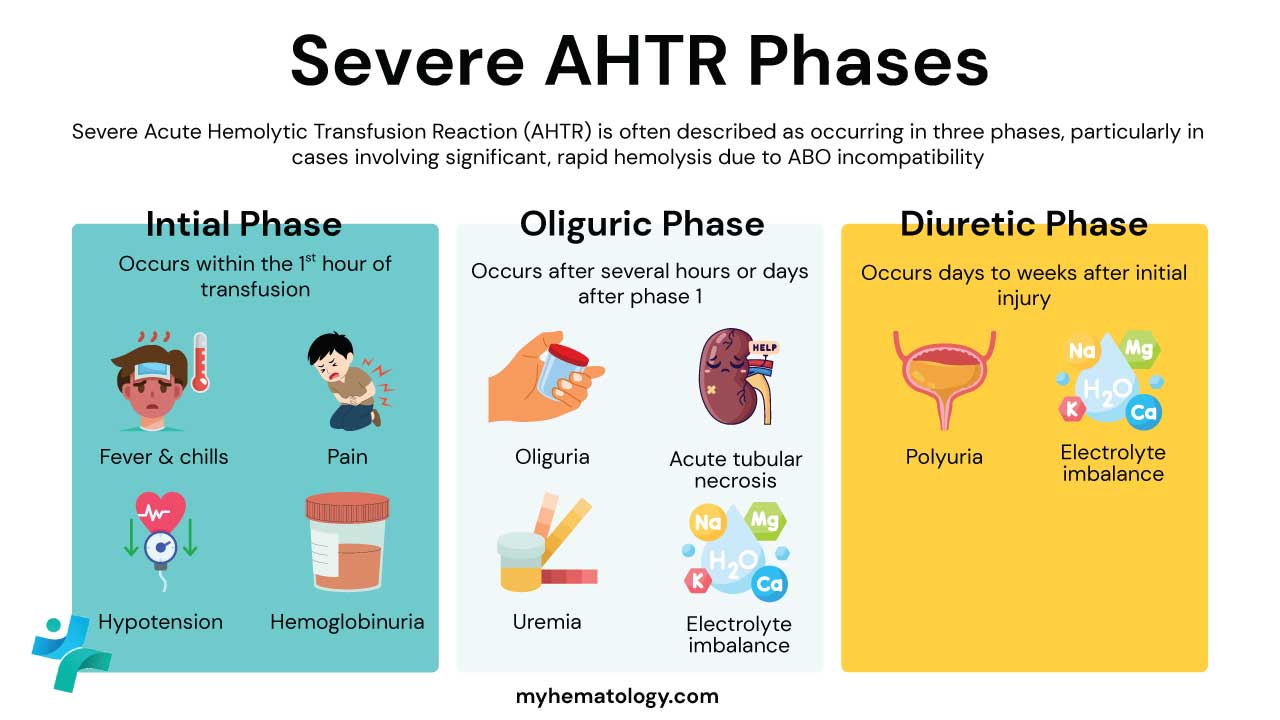

The clinical features of Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction (AHTR) can be divided into 3 phases.

- The initial phase is the hemolytic shock phase: Patients generally develop fever and chills, often accompanied by dyspnoea, tachycardia, hemoglobinuria and severe pain, usually in the lower back. Transfusion of a large volume of ABO-incompatible blood often produces hypotensive shock, oliguria and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

- In the oliguric phase: Some patients may experience renal tubular necrosis with acute renal failure

- Diuretic phase: Fluid and electrolyte imbalance may occur during the recovery from acute renal failure.

How long does it take for an Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction (AHTR) to occur after transfusion?

Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction (AHTR) can occur at any time during or within 24 hours of a blood transfusion. However, they are most likely to occur within the first few hours of the transfusion.

What causes Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction (AHTR)?

The causes of Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction (AHTR) are broadly classified into two categories: Immune-Mediated and Non-Immune-Mediated. The most severe and common causes are immune-mediated, resulting from an incompatibility between the donor’s red blood cells and the recipient’s antibodies.

Immune-Mediated Causes (The Majority)

These reactions occur when pre-existing antibodies in the recipient’s blood attack and destroy the transfused red blood cells (RBCs).

ABO Incompatibility (Most Common and Severe Cause)

This is the primary cause of life-threatening Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction (AHTR).

- Underlying Error: Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction (AHTR) due to ABO incompatibility is almost exclusively the result of a clerical or human error. This includes:

- Misidentification of the patient at the bedside.

- Incorrect labeling of the blood sample drawn from the patient.

- Administering the wrong blood unit to the intended patient.

- Mechanism of Action: ABO antibodies (known as isohemagglutinins, e.g., anti-A, anti-B) are naturally occurring in people lacking the corresponding antigen. These antibodies are usually of the IgM class and are highly efficient at activating the complement cascade. When an incompatible unit is given (e.g., Type A blood to a Type O recipient with preformed anti-A antibodies), the recipient’s antibodies bind to the donor’s RBCs. This binding triggers the complement system, leading to rapid, widespread, and immediate intravascular hemolysis (destruction of RBCs within the blood vessels).

Non-ABO Alloantibodies (Less Common)

These reactions are less common than ABO incompatibility, but they can still cause acute, severe hemolysis.

- Mechanism of Action: These antibodies are typically alloantibodies (IgG class) formed by the recipient following prior exposure to foreign antigens through previous transfusions or pregnancies.

- Common Antigen Systems Implicated:

- Kidd (Jk): The Kidd antibodies (especially Anti-Jka and Anti-Jkb) are notorious for causing acute, often severe, reactions because they are capable of fixing complement, similar to ABO antibodies.

- Duffy (Fy): Duffy antibodies (e.g., Anti-Fya) can also cause significant hemolysis.

- Kell (K): Kell antibodies (e.g., Anti-K) are more often associated with delayed reactions, but they can occasionally cause acute events.

- Detection Challenge: Sometimes, the antibody level in the recipient’s blood may be too low to be detected during routine pre-transfusion screening (a phenomenon known as a “silent” or waning antibody). Once the transfusion introduces the incompatible antigen, the antibody level rapidly rises (anamnestic response) and causes acute hemolysis.

Non-Immune-Mediated Causes

These causes involve the physical or chemical destruction of the transfused RBCs before or during administration, not a reaction by the patient’s immune system.

| Cause | Mechanism of RBC Damage |

| Thermal Injury | Excessive Heat or Freezing: Red cells are highly sensitive to temperature extremes. Overheating a unit (e.g., in an unmonitored blood warmer or placed in hot water) causes the RBC membrane to rupture. Freezing without a cryoprotective agent causes ice crystal formation and osmotic damage. |

| Osmotic Injury | Mixing with Incompatible Solutions: Transfusing blood simultaneously with non-isotonic solutions (such as Dextrose 5% in Water) causes the RBCs to swell and burst (lysis) due to osmotic imbalance. Only Normal Saline (0.9% NaCl) or specific compatible fluids should ever be used to dilute blood. |

| Mechanical Injury | Physical Trauma: Forcing blood through a very high-pressure pump or a very small-bore needle can physically shear the red cell membranes, causing destruction. |

| Bacterial Contamination | Septic Shock: Though technically classified as a “Septic Transfusion Reaction,” the bacteria (e.g., Yersinia enterocolitica or Pseudomonas species) that contaminate blood units often produce potent hemolysins or endotoxins that destroy RBCs, leading to a clinical presentation that rapidly mimics Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction (AHTR) (fever, rigors, shock). |

How is acute hemolytic transfusion reaction (AHTR) treated and managed?

The treatment and management of Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction (AHTR) is a time-critical process focused on three immediate priorities: stopping the transfusion, stabilizing the patient, and preserving renal function.

Immediate Life-Saving Action (The “First 5 Minutes”)

The moment Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction (AHTR) is suspected, action must be taken immediately:

- STOP THE TRANSFUSION: This is the single most critical step. Clamp the transfusion line or disconnect the unit.

- Maintain Venous Access: Do not remove the intravenous line; instead, keep it open by immediately starting a normal saline (0.9% NaCl) infusion via a new line or at the site of the existing cannula to maintain access and provide fluids.

- Assess and Stabilize (ABC): Rapidly check the patient’s Airway, Breathing, and Circulation (vitals, respiratory status, and blood pressure). Activate the hospital’s emergency protocol or call for immediate medical assistance (e.g., rapid response team).

- Clerical Check: Immediately verify the patient’s identity and the blood component tag details to rule out a patient/unit mismatch (clerical error).

Supportive Care and Organ Protection

The principal object of therapy is to treat shock and maintain adequate blood flow to the kidneys, which are highly vulnerable to damage from free hemoglobin.

| Intervention | Purpose | Details |

| Manage Hypotension (Shock) | Restore and maintain adequate blood pressure and circulation. | Administer large volumes of Intravenous (IV) crystalloid fluids (Normal Saline). If hypotension persists, vasopressors (e.g., dopamine, norepinephrine) may be needed to maintain mean arterial pressure (MAP). |

| Maintain Renal Perfusion | Prevent Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) from precipitation of free hemoglobin in the renal tubules. | Monitor urine output via a urinary catheter. The goal is a vigorous urine flow, typically >100 mL/hour (or 1-2 mL/kg/min). |

| Alkaline Diuresis | Flush the kidneys and prevent acid hematin formation. | Use a combination of Loop Diuretics (like Furosemide) and Sodium Bicarbonate infusions. Alkalizing the urine (aiming for a pH of 7.5 to 8.0) helps make the toxic free hemoglobin more soluble, reducing the risk of tubular damage. |

| Treat Bleeding/DIC | Control life-threatening hemorrhage or thrombosis. | If Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC) develops, treat with replacement of clotting factors and platelets (e.g., fresh frozen plasma, cryoprecipitate, and platelet transfusions) as indicated by laboratory values. |

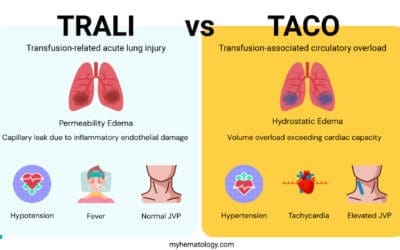

| Respiratory Support | Address breathing difficulties. | Give supplemental oxygen as needed. In cases of severe respiratory distress or the concurrent development of TRALI (Transfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury), mechanical ventilation may be required. |

Laboratory Investigation

Simultaneously with patient care, the following standard AHTR work-up must be performed by the medical and laboratory team:

| Test | Purpose |

| Repeat Clerical Check | Confirm that the blood bag and patient wristband labels match. |

| Plasma Inspection | Check patient’s post-reaction plasma for visual evidence of hemoglobinemia (pink or red color). |

| Direct Antiglobulin Test (DAT) | Check the patient’s post-reaction RBCs for antibody/complement coating (indicates an immune reaction). |

| Repeat Blood Typing & Crossmatch | Re-test the patient’s blood (pre- and post-transfusion) and the donor unit to confirm ABO/Rh incompatibility. |

| Coagulation Screen | Test for signs of DIC (e.g., PT, PTT, Fibrinogen, D-dimer). |

| Bacterial Culture | Rule out Transfusion-Transmitted Bacterial Infection (TTBI), which can mimic AHTR. Send cultures from the patient and the unused portion of the blood bag. |

Advanced and Subsequent Management

- Consultation: In all severe cases, a Hematologist or Transfusion Medicine Specialist must be consulted for expert guidance.

- Refractory Renal Failure: If AKI progresses despite supportive care, the patient may require dialysis.

- Future Transfusions: If subsequent transfusions are necessary, they should be delayed if possible. When transfusions must proceed, the blood bank must issue antigen-negative, phenotype-matched units to avoid further sensitization or reactions.

- Immunomodulation: In rare, severe cases of massive hemolysis or hyperhemolysis (a complication often seen in sickle cell patients), specialized treatments like high-dose IV Immunoglobulin (IVIG), corticosteroids, or even a complement inhibitor (e.g., eculizumab) may be considered, although these are reserved for expert management.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the most common cause of an Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction (AHTR)?

The most common cause of Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction (AHTR) is clerical error (human mistake) that leads to the transfusion of ABO-incompatible red blood cells (e.g., giving Type A blood to a Type O patient).

How quickly does an AHTR occur?

An Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction (AHTR) can occur during the transfusion or within 24 hours of its completion. Severe symptoms, especially with ABO incompatibility, typically start within the first few minutes or hours after transfusion initiation.

What are the key initial symptoms of Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction (AHTR) ?

The symptoms of Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction (AHTR) can vary, but the most common initial signs are:

- Fever and chills (often the first sign).

- Back or flank pain (specifically in the lower back).

- Hemoglobinuria (passing dark or red-colored urine).

- Hypotension (low blood pressure) and shortness of breath.

What is the single most important action when an Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction (AHTR) is suspected?

The transfusion must be STOPPED IMMEDIATELY. The intravenous line should be kept open with a normal saline infusion to maintain venous access, and the patient’s identity and the blood unit label must be rechecked.

What is the principal goal of initial medical treatment for Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction (AHTR) ?

The primary goal is to maintain blood pressure and renal perfusion to prevent acute kidney failure. This is achieved through aggressive fluid resuscitation, blood pressure support, and the use of diuretics (and often alkaline diuresis) to ensure continuous and high urine output.

Glossary of Medical Terms

- Hemolysis: The destruction of red blood cells, resulting in the release of hemoglobin into the bloodstream and urine.

- Antigenically Incompatible: A state where the transfused blood possesses antigens (surface markers) that are recognized as foreign by the recipient’s immune system, leading to a reaction.

- ABO Incompatibility: The most common cause of AHTR, resulting from transfusing blood from one ABO group (e.g., A) into a recipient with preformed antibodies against that group (e.g., Type O recipient).

- Intravascular Hemolysis: The destruction of red blood cells within the blood vessels, often triggered by complement activation. This is characteristic of severe AHTR.

- Preformed Antibodies: Antibodies (like Anti-A or Anti-B) that exist in the recipient’s plasma before any transfusion or known exposure, ready to immediately attack incompatible cells.

- Hemoglobinuria: The presence of free hemoglobin in the urine, causing the urine to appear dark or red-colored; a classic sign of severe hemolysis.

- Hypotension: Abnormally low blood pressure, a sign of shock that occurs due to systemic inflammation and fluid loss in AHTR.

- Tachycardia: An abnormally fast heart rate, often a compensatory response to hypotension (shock).

- Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC): A life-threatening condition caused by severe AHTR where widespread activation of the clotting cascade results in both excessive clotting and severe bleeding.

- Direct Antiglobulin Test (DAT): A critical lab test (also known as the Coombs test) used to detect antibodies or complement components already attached to the surface of a patient’s red blood cells.

- Crossmatch: The final test performed by the blood bank to check for incompatibility between the donor’s red cells and the recipient’s plasma before a transfusion.

- Alkaline Diuresis: A treatment strategy in AHTR involving the use of intravenous fluids, diuretics, and sodium bicarbonate to increase urine output and raise urine pH, which helps flush out free hemoglobin and prevent kidney damage.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Dean L. Blood Groups and Red Cell Antigens [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2005. Chapter 5, The ABO blood group.

- Yamamoto F. ABO+logy: Bioscience of the ABO Blood Groups for High School/College Students & Adults (2023).

- Goldberg S, Hoffman J. Clinical Hematology Made Ridiculously Simple, 1st Edition: An Incredibly Easy Way to Learn for Medical, Nursing, PA Students, and General Practitioners (MedMaster Medical Books). 2021.

- Rout P, Harewood J, Ramsey A, et al. Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction. [Updated 2023 Sep 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448158/

- Hendrickson, J. E., & Fasano, R. M. (2021). Management of hemolytic transfusion reactions. Hematology. American Society of Hematology. Education Program, 2021(1), 704–709. https://doi.org/10.1182/hematology.2021000308

- Zulkeflee, R. H., Hassan, M. N., Hassan, R., Saidin, N. I. S., Zulkafli, Z., Ramli, M., Abdullah, M., Iberahim, S., Roslan, W., Mohd Noor, N. H., & Wan Ab Rahman, W. S. (2023). Acute hemolytic transfusion reaction following ABO-mismatched platelet transfusion: Two case reports. Transfusion and apheresis science : official journal of the World Apheresis Association : official journal of the European Society for Haemapheresis, 62(3), 103658. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transci.2023.103658

- Suddock JT, Crookston KP. Transfusion Reactions. [Updated 2023 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482202/

- Yanjing He, Yang Li, Qiushi Wang, Acute hemolytic transfusion reaction caused by anti-M antibodies: a case report and literature review, Laboratory Medicine, Volume 55, Issue 6, November 2024, Pages 795–801, https://doi.org/10.1093/labmed/lmae038