TL;DR

Antiphospholipid syndrome is an autoimmune disorder where the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks its own cells, specifically phospholipids, which are important for blood clotting. This can lead to blood clots and pregnancy problems.

Types ▾: APS can be primary (occurring alone) or secondary (associated with other autoimmune diseases, especially SLE). It can also be categorized by its main features (thrombotic, obstetric, or both). Catastrophic APS is a rare, severe, and life-threatening form.

Pathogenesis ▾: aPLs are the key players. They bind to phospholipids on cells, triggering cell activation and promoting blood clotting. The complement system also plays a role. Genetic predisposition and environmental triggers may contribute.

- Blood clots, affecting both arteries (stroke, heart attack, peripheral arterial disease) and veins (deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism)

- Microvascular thrombosis leading to livedo reticularis, skin ulcers, and kidney damage

- Women with APS frequently experience obstetric complications, including recurrent pregnancy loss, preeclampsia, HELLP syndrome, fetal growth restriction, and premature birth

- Non-thrombotic manifestations affecting the heart (valvular disease), brain (cognitive dysfunction, seizures, chorea), blood (thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia), and joints (arthralgia)

- Clinical assessment (history of clots or pregnancy problems)

- Laboratory tests for antiphospholipid antibodies (aPLs):

- Lupus anticoagulant (LA) – detected through specific clotting tests (dRVVT, PTT-LA).

- Anticardiolipin antibodies (aCL)

- Anti-β2 glycoprotein I antibodies (anti-β2GPI)

- Imaging studies (to confirm clots)

- Ruling out other conditions

- Anticoagulants (warfarin, heparin, DOACs) to prevent clots. Warfarin requires INR monitoring (target 2.0-3.0). DOACs have fixed dosages.

- Antiplatelet therapy (aspirin).

- Specialized obstetric care for pregnant women with APS (often using aspirin and heparin).

- Immunosuppressants (e.g., hydroxychloroquine) in some cases.

Long-term outlook ▾: Prognosis varies. Long-term anticoagulation is often needed. Regular follow-up is crucial to monitor for recurrent clots, bleeding risks (from anticoagulants), and other complications. Lifestyle changes (no smoking, healthy weight) are important.

*Click ▾ for more information

Introduction

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is an autoimmune disorder characterized by the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (aPLs) in the blood. These antibodies can cause blood clots to form in arteries and veins, as well as pregnancy-related complications such as miscarriages, stillbirths, and premature births.

Autoimmune diseases are a group of disorders where the body’s immune system, which normally defends against harmful invaders like bacteria and viruses, mistakenly attacks its own healthy tissues. This misdirected immune response can lead to inflammation and damage in various parts of the body, depending on the specific autoimmune disease. There are many different types of autoimmune diseases, each with its own set of symptoms and target organs. Some common examples include rheumatoid arthritis (affecting joints), type 1 diabetes (affecting the pancreas), and lupus (affecting multiple organs).

Classification of Antiphopholipid Syndrome

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is primarily classified based on the presence or absence of another underlying autoimmune disease. This leads to two main categories:

- Primary APS: This form of APS occurs on its own, without any other associated autoimmune disease. It is thought to be caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors, but the exact cause is unknown.

- Secondary APS: This form of APS occurs in association with another autoimmune disease, most commonly systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). In this case, the APS is thought to be triggered by the underlying autoimmune disease.

In addition to this primary classification, APS can also be further classified based on clinical manifestations:

- Thrombotic APS: This is the most common form of APS and is characterized by recurrent blood clots in the veins or arteries.

- Obstetric APS: This form of APS is characterized by recurrent miscarriages, premature births, or other pregnancy complications.

- Both thrombotic and obstetric APS: Some people with APS may experience both blood clots and pregnancy complications.

Finally, APS can also be classified based on the presence of life-threatening multiorgan involvement, known as catastrophic APS. This is a rare but severe form of APS that can lead to multiple organ failure and death.

Pathogenesis

Antiphospholipid antibodies (aPLs) are the hallmark of APS. These antibodies can activate the complement system, leading to a cascade of events that can damage blood vessels and other tissues. Complement activation can also lead to the formation of blood clots in both arteries and veins. The complement system can be activated through three different pathways: the classical pathway, the lectin pathway, and the alternative pathway. aPLs can activate the complement system through all three of these pathways.

Once the complement system is activated, it can lead to the formation of a complex called the membrane attack complex (MAC). The MAC can insert itself into the membranes of cells, causing them to lyse (burst). This can lead to inflammation and damage to the blood vessels.

In addition to their role in thrombosis, aPLs can also interfere with the normal function of the placenta, which can lead to pregnancy complications. aPLs can bind to phospholipids on the surface of placental cells, which can disrupt the flow of blood and nutrients to the fetus.

There are a number of different types of aPLs, including lupus anticoagulant (LA), anticardiolipin antibodies (aCL), and anti-β2 glycoprotein I antibodies (anti-β2GPI). The presence of any of these antibodies can increase the risk of APS-related complications.

The exact cause of APS is not known, but it is thought to be a combination of genetic and environmental factors. Some people may be genetically predisposed to develop APS. This means that they have certain genes that make them more likely to develop the condition. However, having these genes does not mean that they will definitely develop APS. Environmental triggers, such as infections, may also play a role in the development of APS.

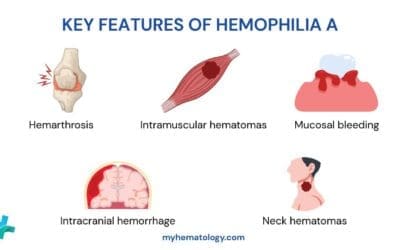

Clinical Features of Antiphospholipid Syndrome

Antiphospholipid Syndrome (APS) can manifest in a variety of ways, affecting different organ systems. Its clinical features are broadly categorized into thrombotic (related to blood clots) and obstetric (related to pregnancy) complications, though other non-thrombotic manifestations can also occur.

Vascular Thrombosis (Blood Clots)

- Arterial Thrombosis

- Stroke/TIA (Transient Ischemic Attack): Especially in younger individuals. Can be the first manifestation of APS.

- Myocardial Infarction (Heart Attack): Even in the absence of traditional risk factors.

- Peripheral Arterial Disease: Causing pain and reduced blood flow to limbs.

- Other Arterial Events: Clots in arteries supplying other organs (kidneys, intestines, etc.) can cause organ-specific problems.

- Venous Thrombosis

- Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT): Usually in the legs, causing pain, swelling, and redness. A common initial presentation.

- Pulmonary Embolism (PE): A potentially life-threatening condition where a clot travels to the lungs.

- Other Venous Sites: Clots can occur in veins of the arms, abdomen (Budd-Chiari syndrome), or brain (cerebral venous sinus thrombosis).

- Microvascular Thrombosis

- Pregnancy Complications

- Livedo Reticularis: A net-like, purplish rash on the skin.

- Skin Ulcers: Especially around the ankles.

- APS Nephropathy: Kidney damage due to microthrombi.

Obstetric Complications

- Recurrent Pregnancy Loss: Especially in the first trimester, but can occur later. A hallmark of APS.

- Pre-eclampsia/Eclampsia: High blood pressure and organ damage during pregnancy.

- HELLP Syndrome: A severe form of pre-eclampsia with liver and blood clotting problems.

- Fetal Growth Restriction: The baby doesn’t grow at the expected rate in the womb.

- Premature Birth: Due to complications of APS.

Non-Thrombotic Manifestations

- Cardiac

- Valvular Heart Disease: Especially Libman-Sacks endocarditis (vegetations on heart valves). Libman-Sacks vegetations are sterile abnormal growths of tissue around the heart valves with an autoimmune-mediated inflammatory and thrombotic pathogenesis.

- Myocardial Dysfunction: Heart muscle problems.

- Neurological

- Cognitive Dysfunction: Problems with memory, concentration, and thinking.

- Seizures

- Chorea: Involuntary, jerky movements.

- Headaches/Migraines

- Hematological

- Thrombocytopenia: Low platelet count, which can paradoxically increase the risk of clotting.

- Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia

- Skin

- Livedo Reticularis: As mentioned above.

- Skin Ulcers: Often in the legs.

- Renal

- APS Nephropathy: Kidney disease due to microthrombi.

- Other

- Fatigue: A common symptom.

- Arthralgia/Arthritis: Joint pain.

It’s important to remember that not everyone with APS will experience all of these features. The presentation can vary significantly from person to person. Some individuals may only have a history of pregnancy complications, while others may primarily experience thrombotic events. The diagnosis of APS requires a careful evaluation of the patient’s clinical history, along with specific laboratory tests.

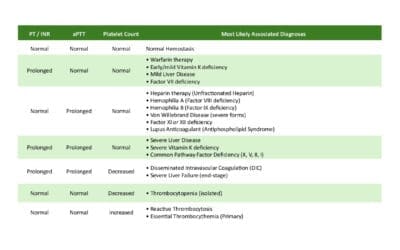

Laboratory Investigations for Antiphospholipid Syndrome

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is diagnosed through a combination of clinical evaluation and laboratory testing. The laboratory investigations focus on detecting specific antibodies associated with APS, known as antiphospholipid antibodies (aPLs).

Lupus Anticoagulant (LA) test

Lupus anticoagulant (LA) is a type of antiphospholipid antibody that can interfere with blood clotting tests in the lab. It’s important to understand that LA doesn’t actually prevent blood from clotting in the body (in vivo). Instead, it causes blood to take longer to clot in test tubes (in vitro).

Lupus anticoagulant (LA) isn’t measured directly like other substances in the blood. Instead, its presence is inferred through a series of tests because there’s no single, standardized method. A multi-step approach is necessary to accurately identify or rule out this autoantibody.

Initially, two screening tests are recommended to detect LA: the dilute Russell viper venom test (dRVVT) and a specific type of partial thromboplastin time test designed to be sensitive to LA (PTT-LA). The PTT-LA uses reagents with low phospholipid levels to enhance its sensitivity to LA.

If these initial tests suggest LA, further testing is performed to confirm the finding. This usually involves:

- Mixing Studies: The patient’s plasma is mixed with an equal amount of normal plasma, and then either a PTT or dRVVT is performed on the mixture. This helps determine if the clotting abnormality is due to an inhibitor like LA.

- Correction/Neutralization Tests: An excess of phospholipids is added to the patient’s sample, and then a PTT-LA or dRVVT is performed again. When a PTT-LA is used in this step, it’s sometimes called a hexagonal phase phospholipid neutralization assay. This step assesses if the added phospholipids “correct” or neutralize the effect of LA, which is characteristic of this autoantibody.

The results from these confirmatory tests are then compared to the initial screening test results. A trained laboratory technologist or pathologist interprets the complete set of results to determine if LA is truly present.

Anticardiolipin Antibodies (aCL)

aCLs are antibodies that bind to cardiolipin, a substance found in cell membranes. They are measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA). aCLs are classified into IgG, IgM, and IgA isotypes, with IgG being the most clinically relevant in APS. High levels of aCL, particularly IgG isotype, are associated with increased risk of thrombosis and pregnancy complications in APS.

Anti-β2 Glycoprotein I Antibodies (anti-β2GPI)

Anti-β2GPI antibodies bind to β2 glycoprotein I, a protein that helps regulate blood clotting. Like aCLs, they are measured using ELISA and classified into IgG, IgM, and IgA isotypes. Anti-β2GPI antibodies, especially IgG isotype, are strongly associated with APS-related complications.

“Triple Positivity”

The presence of all three aPLs (LA, aCL, and anti-β2GPI) is referred to as “triple positivity.” Individuals with triple positivity are considered to have the highest risk for APS-related complications.

Important Considerations

- aPLs can be present in individuals without APS, so the diagnosis requires a combination of clinical and laboratory findings.

- aPL testing should be performed on two separate occasions, at least 12 weeks apart, to confirm the diagnosis of APS.

- The interpretation of aPL test results should be done in conjunction with the patient’s clinical history and other relevant investigations.

Differential Diagnosis for APS

- Other autoimmune diseases: SLE, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis, and other connective tissue disorders can have overlapping symptoms with antiphospholipid syndrome.

- Thrombotic disorders: Inherited or acquired thrombophilias, such as those mentioned above, can cause blood clots similar to those seen in antiphospholipid syndrome.

- Cardiovascular diseases: Conditions like atherosclerosis, heart valve disease, and heart failure can present with similar symptoms to antiphospholipid syndrome, such as chest pain or stroke.

- Neurological disorders: Stroke, transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), and other neurological conditions can have symptoms similar to those seen in antiphospholipid syndrome, such as weakness or numbness.

- Obstetric complications: Other causes of recurrent pregnancy loss, such as genetic abnormalities or uterine abnormalities, need to be considered.

Relevant Investigations to Rule Out Other Conditions

Antinuclear Antibodies (ANA)

ANA is a group of autoantibodies that target the cell’s nucleus. A positive ANA test can be seen in various autoimmune diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), which is closely associated with antiphospholipid syndrome. ANA testing can help determine if the patient has another autoimmune condition alongside or instead of antiphospholipid syndrome.

Tests for Other Autoimmune Diseases

Depending on the clinical presentation, doctors may order tests for other autoimmune diseases.

- Rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies for rheumatoid arthritis.

- Anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) and anti-Smith antibodies for SLE.

- Anti-Scl-70 and anti-centromere antibodies for systemic sclerosis.

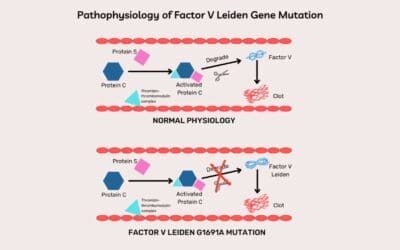

Thrombophilia Workup

Thrombophilia refers to an increased tendency to form blood clots due to inherited or acquired factors. In cases of thrombosis (blood clots), it’s essential to rule out other causes of thrombophilia, such as:

- Factor V Leiden mutation

- Prothrombin gene mutation

- Antithrombin deficiency

- Protein C or S deficiency

These tests help determine if the patient’s blood clots are due to antiphospholipid syndrome or another underlying thrombophilic condition.

Other Investigations

Depending on the clinical presentation, other investigations may be considered, such as:

- Complete blood count (CBC) to assess for anemia or thrombocytopenia (low platelet count), which can be seen in antiphospholipid syndrome and other conditions.

- Comprehensive metabolic panel to evaluate organ function and identify any abnormalities.

- Imaging studies (e.g., ultrasound, CT scan, MRI) to visualize blood clots or assess for other structural abnormalities.

Classification Criteria for Antiphospholipid Syndrome Research

Revised Sapporo Criteria

The revised Sapporo criteria for antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) are a set of guidelines used to classify patients with APS for research purposes. They were first published in 1999 and revised in 2006. The criteria include both clinical and laboratory components, and a patient must meet at least one criterion from each category to be classified as having antiphospholipid syndrome.

Clinical criteria

- Vascular thrombosis: This includes blood clots in arteries or veins, such as deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE), stroke, or heart attack.

- Pregnancy morbidity: This includes recurrent miscarriages, stillbirths, or premature births due to complications of antiphospholipid syndrome, such as preeclampsia or placental insufficiency.

Laboratory criteria

- Lupus anticoagulant (LA)

- Anticardiolipin antibodies (aCL)

- Anti-β2 glycoprotein I antibodies (anti-β2GPI)To meet the laboratory criteria for antiphospholipid syndrome, a patient must have at least one of these antibodies present in their blood on two or more occasions, at least 12 weeks apart.

The revised Sapporo criteria are important for research because they help to ensure that studies of antiphospholipid syndrome are conducted on a consistent and comparable population of patients. However, it is important to note that these criteria are not intended for use in diagnosing antiphospholipid syndrome in clinical practice. The diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome is based on a combination of clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings, and the revised Sapporo criteria are just one tool that can be used to help make the diagnosis.

The 2023 ACR/EULAR Antiphospholipid Syndrome Classification Criteria

The 2023 ACR/EULAR Antiphospholipid Syndrome Classification Criteria were developed by a joint task force of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR). These criteria are intended for use in research settings to identify patients with antiphospholipid syndrome for observational studies and clinical trials. They are not intended for use in diagnosing antiphospholipid syndrome in clinical practice, although they may inform the diagnostic evaluation.

The 2023 ACR/EULAR APS classification criteria are more comprehensive than the revised Sapporo criteria and include a wider range of clinical and laboratory features. The criteria are organized into two main domains:

Clinical domain: This domain includes six clinical criteria, each of which is assigned a weighted score based on its association with antiphospholipid syndrome.

- Arterial thrombosis

- Venous thrombosis

- Microvascular thrombosis

- Obstetric APS

- Cardiac manifestations

- Other manifestations (such as skin ulcers, livedo reticularis, and thrombocytopenia)

| Clinical Criterion | Weight (Points) |

| Arterial Thrombosis (Confirmed by imaging) | 3 |

| Venous Thrombosis (Confirmed by imaging) | 3 |

| Microvascular Thrombosis (e.g., APS nephropathy) | 3 |

| Obstetric APS (≥1 pregnancy loss ≥10 weeks, ≥1 premature birth <34 weeks due to pre-eclampsia/placental insufficiency, or ≥3 consecutive pregnancy losses <10 weeks) | 3 |

| Cardiac Manifestations (e.g., valvular heart disease, Libman-Sacks endocarditis, myocardial dysfunction) | 2 |

| Other Manifestations (e.g., skin ulcers, livedo reticularis, thrombocytopenia) | 1 |

Laboratory domain: This domain includes three laboratory criteria, each of which is assigned a weighted score based on its association with APS.

- Lupus anticoagulant (LA)

- Anticardiolipin antibodies (aCL)

- Anti-β2 glycoprotein I antibodies (anti-β2GPI)

| Laboratory Criterion | Weight (Points) |

| Lupus Anticoagulant (LA) present | 3 |

| Anticardiolipin Antibodies (aCL) IgG ≥40 GPL or ≥40 IU/mL | 3 |

| Anti-β2 Glycoprotein I Antibodies (anti-β2GPI) IgG ≥40 GPL or ≥40 IU/mL | 3 |

To meet the 2023 ACR/EULAR APS classification criteria, a patient must have at least one positive antiphospholipid antibody (aPL) test within 3 years of identification of an aPL-associated clinical criterion. Patients accumulating at least three points each from the clinical and laboratory domains are classified as having antiphospholipid syndrome.

The 2023 ACR/EULAR APS classification criteria were developed using rigorous methodology with multidisciplinary international input. The criteria were validated in a large cohort of patients with and without antiphospholipid syndrome, and they were found to have high specificity and sensitivity for antiphospholipid syndrome.

The 2023 ACR/EULAR APS classification criteria are a valuable tool for researchers studying antiphospholipid syndrome. The criteria are more comprehensive and specific than the revised Sapporo criteria, and they are based on the latest understanding of antiphospholipid syndrome.

Treatment and Management of Antiphospholipid Syndrome

The treatment and management of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) aims to prevent blood clots, manage pregnancy complications, and address any other associated symptoms. Treatment is tailored to the individual patient based on their specific clinical manifestations and risk factors.

Anticoagulation

Anticoagulants are the cornerstone of antiphospholipid syndrome treatment, as they help prevent blood clots from forming. The choice of anticoagulant depends on the patient’s specific situation and risk factors.

Common anticoagulants used in antiphospholipid syndrome include:

- Warfarin: A vitamin K antagonist that reduces the production of clotting factors. It requires regular monitoring of the international normalized ratio (INR) to ensure proper dosing.

- Heparin: An injectable anticoagulant that works quickly to prevent blood clots. It is often used in acute situations or during pregnancy.

- Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs): Newer anticoagulants that directly inhibit specific clotting factors. They offer more predictable dosing and do not require routine monitoring of INR. Several DOACs are available, including dabigatran (Pradaxa), rivaroxaban (Xarelto), apixaban (Eliquis), and edoxaban (Savaysa). The appropriate DOAC dosage depends on the specific DOAC being used, as well as individual patient factors like kidney function, age, and other medications. DOACs generally have a lower risk of major bleeding compared to warfarin and don’t require frequent blood tests. However, they are not suitable for all patients, and warfarin may still be the preferred option in certain situations.

Duration of Therapy: The duration of anticoagulation therapy for APS is highly individualized and depends on several factors:

- History of Thrombosis: If the individual had a blood clot, long-term anticoagulation is usually recommended, often indefinitely.

- Risk Factors: The presence of other risk factors for clotting (e.g., other autoimmune diseases, inherited clotting disorders) may influence the duration.

- Recurrent Events: If the patient had multiple blood clots despite anticoagulation, lifelong therapy is typically necessary.

- Pregnancy: Anticoagulation management during pregnancy is a specialized area and requires careful monitoring and adjustments.

Indefinite Anticoagulation: In many cases, especially after a first or recurrent thrombotic event, indefinite (lifelong) anticoagulation is recommended for antiphospholipid syndrome patients. This is because the risk of future clots can remain elevated. Long-term anticoagulation is a critical part of managing antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) to prevent future blood clots. The International Normalized Ratio (INR) is a standardized way to measure how long it takes the blood to clot. It’s used to monitor the effectiveness of warfarin. For most antiphospholipid syndrome patients on warfarin, the target INR is between 2.0 and 3.0. This range is considered therapeutic, meaning it’s effective at preventing clots without significantly increasing the risk of bleeding. An INR below 2.0 increases the risk of clot formation, while an INR above 3.0 increases the risk of bleeding.

When taking warfarin, regular blood tests are essential to monitor the INR and ensure it stays within the target range. Factors like diet, other medications, and overall health can affect INR levels.

Important Considerations

- Bleeding Risk: All anticoagulants carry a risk of bleeding. It’s important to be aware of the signs of bleeding (e.g., nosebleeds, unusual bruising, blood in urine or stool) and require prompt medical attention if they occur.

- Medication Interactions: Many medications can interact with warfarin and DOACs, so it’s crucial to know about all the medications taken, including over-the-counter drugs and supplements.

- Regular Follow-up: Regular follow-up is essential to monitor the effectiveness of anticoagulation, adjust the dosage if needed, and address any concerns or side effects.

Antiplatelet Therapy

Antiplatelet medications, such as low-dose aspirin, may be used in combination with anticoagulants to further reduce the risk of blood clots. Aspirin helps prevent platelets from sticking together and forming clots.

Obstetric Management

Pregnant women with antiphospholipid syndrome require specialized care to prevent pregnancy complications, such as recurrent miscarriages, preeclampsia, and fetal growth restriction. Treatment during pregnancy typically involves a combination of:

- Low-dose aspirin: To help prevent placental blood clots and improve fetal circulation.

- Heparin: To provide additional anticoagulation and reduce the risk of pregnancy complications.

- Close monitoring of the mother and fetus is essential throughout pregnancy.

Immunosuppression

In some cases, immunosuppressive medications may be used to suppress the immune system and reduce the production of antiphospholipid antibodies. Immunosuppressants, such as hydroxychloroquine, may be considered in patients with recurrent pregnancy loss or other autoimmune manifestations of APS.

Other Management Strategies

- Lifestyle modifications: Maintaining a healthy lifestyle, including regular exercise, a balanced diet, and avoiding smoking, can help reduce the risk of blood clots.

- Management of associated conditions: If the patient has other autoimmune diseases, such as SLE, it’s important to manage those conditions as well.

- Monitoring and follow-up: Regular monitoring and follow-up with healthcare professionals are essential to ensure the effectiveness of treatment and to detect any potential complications.

It’s important to note that the treatment and management of APS should be individualized based on the patient’s specific needs and risk factors.

Prognosis and Long-Term Follow-up

The long-term prognosis for patients with antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is variable and depends on several factors, including the severity of the disease, the presence of other medical conditions, and adherence to treatment. While antiphospholipid syndrome is a chronic condition, many individuals can lead relatively normal lives with appropriate management. However, it’s important to be aware of the potential for long-term complications and the need for ongoing monitoring.

- History of Thrombosis: Patients with a history of blood clots (venous or arterial) are at increased risk for recurrent thrombotic events. This risk can be reduced significantly with effective anticoagulation therapy, but it’s not entirely eliminated. The risk is highest in the first few years after an initial clot.

- Obstetric Complications: Women with antiphospholipid syndrome who have experienced pregnancy complications (e.g., recurrent miscarriages, preeclampsia) face an increased risk of similar complications in future pregnancies. Careful management during pregnancy is essential.

- Presence of Other Autoimmune Diseases: APS can occur alone (primary APS) or in association with other autoimmune disorders, most commonly systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (secondary APS). The presence of other autoimmune conditions can influence the overall prognosis, as these conditions may have their own set of complications. For example, if someone has both SLE and APS, their long-term outlook will be influenced by both diseases.

- Catastrophic APS: This is a rare but life-threatening variant of APS characterized by widespread thrombosis and multi-organ failure. The prognosis for catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome is guarded, and it requires intensive medical management. Even if someone survives a catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome event, they may have long-term health issues.

- Non-Thrombotic Manifestations: APS can also manifest with non-thrombotic features, such as cardiac valve disease, neurological problems (e.g., cognitive dysfunction, seizures), or skin manifestations. The long-term impact of these manifestations depends on their severity and response to treatment.

- Adherence to Treatment: Adherence to prescribed anticoagulation therapy is crucial for preventing recurrent thrombosis. Poor adherence can significantly increase the risk of complications and worsen the long-term prognosis.

- Lifestyle Factors: Lifestyle factors, such as smoking, obesity, and lack of exercise, can also influence the long-term prognosis in antiphospholipid syndrome. Maintaining a healthy lifestyle can help reduce the risk of complications.

- Long-Term Complications of Anticoagulation: While anticoagulants are essential for managing antiphospholipid syndrome, they also carry a risk of bleeding complications, especially with long-term use. This can range from minor bleeding (e.g., nosebleeds, gum bleeding, easy bruising) to more serious bleeding events. Major bleeding, such as gastrointestinal bleeding, intracranial hemorrhage (bleeding in the brain), or bleeding into a major joint, can be life-threatening. Careful monitoring and management are necessary to minimize this risk.

Risk of Recurrence

The risk of recurrence is highest in the first few years after an initial thrombotic event. However, the risk persists long-term, emphasizing the need for ongoing management. The risk of recurrent thrombosis (blood clots) or obstetric complications in APS varies depending on several factors, including

- Initial Event: Individuals who have already experienced a thrombotic event are at a higher risk of recurrence compared to those who have only had obstetric complications.

- Type of Event: Arterial thromboses (e.g., stroke, heart attack) may carry a higher risk of recurrence than venous thromboses (e.g., DVT, PE), although both are significant.

- Presence of Other Risk Factors: Other risk factors for clotting (e.g., smoking, obesity, other autoimmune diseases, inherited clotting disorders) can increase the risk of recurrence.

- Persistence of aPLs: The continued presence of high levels of antiphospholipid antibodies (aPLs) increases the risk. “Triple positivity” (presence of lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin, and anti-β2 glycoprotein I antibodies) is considered particularly high risk.

- Adherence to Therapy: Poor adherence to prescribed anticoagulation therapy is a major risk factor for recurrent thrombosis.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Yun Z, Duan L, Liu X, Cai Q, Li C. An update on the biologics for the treatment of antiphospholipid syndrome. Front Immunol. 2023 May 19;14:1145145. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1145145. PMID: 37275894; PMCID: PMC10237350.

- Schreiber K, Hunt BJ. Managing antiphospholipid syndrome in pregnancy. Thromb Res. 2019 Sep;181 Suppl 1:S41-S46. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(19)30366-4. PMID: 31477227.

- Hubben A, McCrae KR. How to diagnose and manage antiphospholipid syndrome. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2023 Dec 8;2023(1):606-613. doi: 10.1182/hematology.2023000493. PMID: 38066904; PMCID: PMC10727028.

- Sammaritano LR. Antiphospholipid syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2020 Feb;34(1):101463. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2019.101463. Epub 2019 Dec 19. PMID: 31866276.