TL;DR

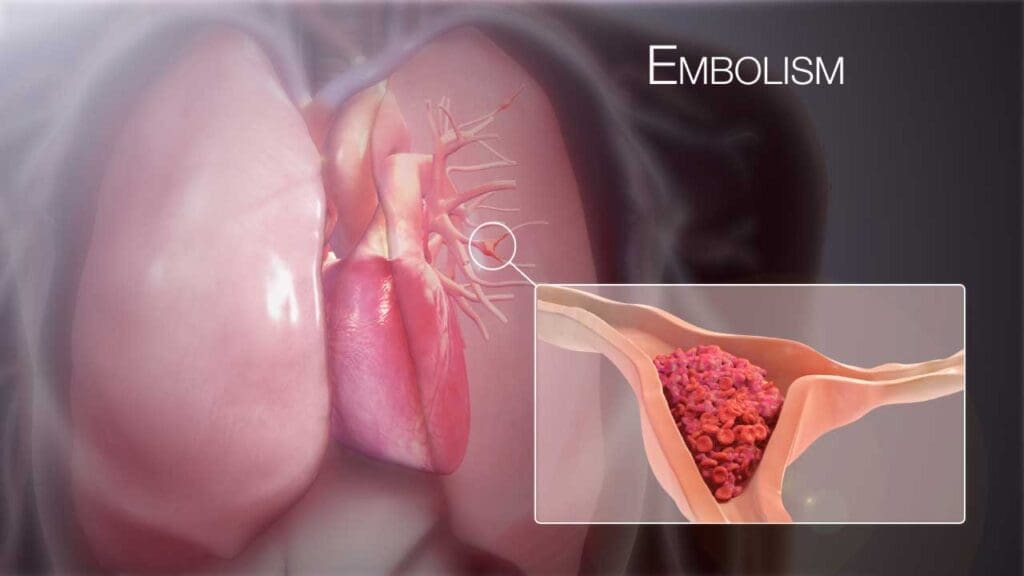

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a blockage in lung arteries, usually from a DVT.

- Risk factors involve Virchow’s triad ▾: hypercoagulability, venous stasis, endothelial injury.

- Pathophysiology ▾: Increased pulmonary resistance, right heart strain, V/Q mismatch.

- Symptoms ▾: sudden dyspnea, chest pain, cough.

- Diagnosis ▾: Wells/Geneva scores, D-dimer, CTPA (gold standard).

- Treatment ▾: Anticoagulation (DOACs, heparin), thrombolysis (for massive PE), supportive care.

- Complications ▾: Pulmonary hypertension, CTEPH, right heart failure.

- Prognosis ▾: Varies based on severity and treatment; early intervention is crucial.

*Click ▾ for more information

Introduction

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is when a blockage in one of the pulmonary arteries in the lungs occurs. This blockage is most often caused by a blood clot that travels from the deep veins in the legs (deep vein thrombosis or DVT) to the lungs. Because it can severely restrict blood flow to the lungs, a pulmonary embolism (PE) can be a life-threatening condition.

Prevalence and Incidence

The estimated annual incidence of pulmonary embolism is approximately 60 to 70 per 100,000 people. Some sources state that the estimated annual incidence of pulmonary embolism worldwide is approximately 1 per 1000 people.

Pulmonary embolism is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality. It’s a major cause of cardiovascular death, ranking third after heart attack and stroke. A substantial portion of individuals with untreated pulmonary embolism may experience fatal outcomes, highlighting the urgency of prompt diagnosis and treatment. Thus, many cases of sudden death are thought to be from undiagnosed pulmonary embolism.

The symptoms of pulmonary embolism can be nonspecific, making diagnosis difficult. This can lead to delays in treatment, increasing the risk of adverse outcomes. Even with treatment, pulmonary embolism can lead to long-term complications such as chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH), which can significantly impact a patient’s quality of life. Often pulmonary embolism is caused by DVT which means that identifying people at risk for DVT is also vital to preventing many instances of pulmonary embolism.

Risk Factors and Causes of PE

Virchow’s Triad

This is the cornerstone for understanding the pathophysiology of venous thromboembolism (VTE), which includes pulmonary embolism (PE) and deep vein thrombosis (DVT). It consists of three primary factors.

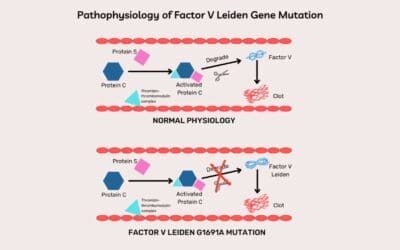

- Hypercoagulability: This refers to an increased tendency of the blood to clot. Causes include:

- Inherited thrombophilia (e.g., Factor V Leiden, prothrombin gene mutation, deficiencies in protein C, protein S, or antithrombin).

- Acquired conditions (e.g., malignancy, pregnancy, hormone therapy, antiphospholipid syndrome).

- Venous Stasis: This refers to slowed or stagnant blood flow in the veins. Causes include:

- Prolonged immobilization (e.g., bed rest, long flights, paralysis).

- Venous obstruction (e.g., tumors, obesity).

- Varicose veins.

- Endothelial Injury: This occurs due to damages to the inner lining of blood vessels. Causes include:

- Trauma or surgery.

- Central venous catheters.

- Inflammation.

Acquired Risk Factors

These are factors that develop during a person’s lifetime.

- Prolonged Immobilization: Extended periods of inactivity allow blood to pool in the veins, increasing the risk of clot formation.

- Surgery: Especially orthopedic surgeries (hip or knee replacement) and major abdominal or pelvic surgeries. Surgical procedures can cause both endothelial damage, and immobility.

- Malignancy: Cancer cells can release procoagulant factors, increasing the risk of hypercoagulability. Some cancer treatments can also increase the risk.

- Pregnancy and Postpartum Period: Hormonal changes and compression of the inferior vena cava by the enlarging uterus increase the risk of venous stasis and hypercoagulability.

- Hormone Therapy: Oral contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy containing estrogen can increase the risk of clotting.

- Trauma: Injuries can damage blood vessels and lead to clot formation.

- Advanced Age: Older adults have an increased risk of clotting due to age-related changes in the coagulation system and decreased mobility.

- Obesity: Obesity is associated with increased venous stasis and a prothrombotic state.

- Smoking: Smoking damages blood vessels and increases the risk of clotting.

- Central Venous Catheters: These can damage the vessel wall and increase the risk of clot formation.

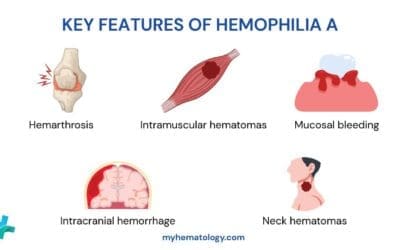

Inherited Thrombophilia

These are genetic conditions that increase the risk of clotting.

- Factor V Leiden Mutation.

- Prothrombin Gene Mutation

- Protein C and S Deficiency

- Antithrombin Deficiency

Less Common Causes

- Fat Embolism: Fat globules can enter the bloodstream after a fracture and travel to the lungs.

- Amniotic Fluid Embolism: A rare but life-threatening condition that occurs during childbirth.

- Septic Embolism: Infected clots can break off and travel to the lungs.

- Tumor Embolism: Pieces of a tumor can break off, and travel to the lungs.

Pathophysiology of Pulmonary Embolism

Pulmonary embolism’s pathophysiology involves a cascade of events, starting with the obstruction of pulmonary arteries, leading to hemodynamic instability, respiratory compromise, and neurohumoral responses. The severity of these changes depends on the size and location of the embolus, as well as the patient’s underlying cardiopulmonary function.

The vast majority of pulmonary embolisms originate from deep vein thrombosis (DVT), typically in the proximal deep veins of the legs (iliac, femoral, and popliteal veins). These thrombi break off and travel through the inferior vena cava to the right atrium, right ventricle, and finally, the pulmonary arteries.

Hemodynamic Consequences

- Increased Pulmonary Vascular Resistance: The embolus obstructs blood flow in the pulmonary arteries, leading to a rapid increase in pulmonary vascular resistance.

- Right Ventricular Strain and Failure: The right ventricle (RV) has to work harder to pump blood against the increased resistance. This leads to RV dilation and, in severe cases, RV failure.

- Decreased Cardiac Output: RV failure results in reduced blood flow to the left ventricle, leading to decreased cardiac output. This can cause systemic hypotension and shock.

- Pulmonary Hypertension: The blockage of pulmonary arteries results in increased pressure in the pulmonary circulation.

Respiratory Consequences

- Ventilation-Perfusion (V/Q) Mismatch: The obstructed pulmonary arteries prevent blood flow to ventilated alveoli, creating areas of high V/Q ratios (ventilation without perfusion). This mismatch leads to hypoxemia (low blood oxygen levels).

- Hypoxemia: V/Q mismatch is the primary cause of hypoxemia in pulmonary embolism. Additionally, atelectasis (collapse of alveoli) can occur, further contributing to hypoxemia.

- Alveolar Dead Space: The areas of the lungs that are ventilated but not perfused contribute to alveolar dead space, meaning that the ventilated air does not participate in gas exchange.

- Pulmonary Infarction: If the obstruction is severe enough, it can lead to pulmonary infarction, where the lung tissue distal to the blockage dies. This is more common in smaller, peripheral emboli. Pleuritic chest pain and hemoptysis can occur with pulmonary infarction.

Neurohumoral Responses

The body initiates several neurohumoral responses to compensate for the hemodynamic and respiratory changes.

- Sympathetic Nervous System Activation: This leads to tachycardia, vasoconstriction, and increased myocardial contractility.

- Release of Inflammatory Mediators: These mediators can contribute to bronchoconstriction and pulmonary vasoconstriction.

- Reflex Tachypnea: The lungs stimulate faster breathing in an attempt to gain more oxygen.

Signs and Symptoms of Pulmonary Embolism

The signs and symptoms of pulmonary embolism (PE) can vary widely, ranging from subtle to life-threatening. This variability makes diagnosis challenging.

The severity of symptoms and signs depends on the size and location of the embolus, as well as the patient’s underlying cardiopulmonary status. It’s crucial to have a high index of suspicion for pulmonary embolism especially in patients with risk factors. Many of the signs and symptoms above can be caused by other illnesses. This is why a good clinical history, risk factor evaluation, and diagnostic testing are so important.

Symptoms

- Sudden Onset of Dyspnea (Shortness of Breath): This is the most common symptom. It can range from mild to severe, depending on the size of the embolus.

- Chest Pain (Pleuritic): Often described as sharp, stabbing pain that worsens with deep breathing or coughing. This type of pain is more common with peripheral emboli that cause pulmonary infarction.

- Cough: May be dry or productive. Hemoptysis (coughing up blood) may occur, particularly with pulmonary infarction.

- Anxiety/Restlessness

- Lightheadedness or Syncope (Fainting): These symptoms indicate severe hemodynamic compromise.

- Palpitations (Rapid or Irregular Heartbeat)

- Leg Pain or Swelling: This is a sign of DVT, the common cause of pulmonary embolism.

Signs

- Tachypnea (Rapid Breathing)

- Tachycardia (Rapid Heart Rate)

- Hypoxia (Low Oxygen Saturation): Measured by pulse oximetry or arterial blood gases.

- Hypotension (Low Blood Pressure): Indicates severe hemodynamic instability, particularly in massive pulmonary embolism.

- Crackles or Wheezing (Abnormal Lung Sounds): May be present, but lung examination can be normal.

- Increased Intensity of the Second Heart Sound (S2): Particularly the pulmonary component, suggesting pulmonary hypertension.

- Right Ventricular Heave: A palpable lift along the left sternal border. This indicates right ventricular strain.

- Leg Swelling, Tenderness, or Warmth: Suggests the presence of DVT.

- Signs of Right Heart Failure: Such as jugular venous distention (JVD) and peripheral edema.

- Fever: May be present, especially with pulmonary infarction.

- S1Q3T3: This is a classic, but not sensitive or specific, ECG finding in pulmonary embolism. It consists of a large S wave in lead I, a Q wave in lead III, and an inverted T wave in lead III.

Approach to Diagnosing Pulmonary Embolism (PE)

The approach to diagnosing pulmonary embolism involves a systematic process that combines clinical assessment, risk stratification, laboratory tests, and imaging studies.

Clinical Assessment and Risk Stratification

- Detailed History and Physical Examination: Gather information about the patient’s symptoms, risk factors, and medical history and perform a thorough physical examination, paying attention to signs of DVT, right heart strain, and respiratory distress.

- Clinical Probability Assessment: Use validated scoring systems, such as the Wells score or the Revised Geneva score, to estimate the pretest probability of pulmonary embolism. These scores consider factors like clinical symptoms, risk factors, and alternative diagnoses.

Wells Score for Pulmonary Embolism

| Clinical Feature | Points |

| Clinical signs and symptoms of DVT (leg swelling, pain with palpation of deep veins) | 3.0 |

| Pulmonary embolism is the most likely diagnosis, or equally likely | 3.0 |

| Heart rate > 100 beats/min | 1.5 |

| Immobilization (≥ 3 days) or surgery in the previous 4 weeks | 1.5 |

| Previous objectively diagnosed PE or DVT | 1.5 |

| Hemoptysis | 1.0 |

| Malignancy (treated within 6 months or currently receiving palliative treatment) | 1.0 |

Interpretation

- High probability: > 6.0 points

- Moderate probability: 2.0 to 6.0 points

- Low probability: < 2.0 points

Revised Geneva Score for Pulmonary Embolism

| Clinical Feature | Points |

| Age > 65 years | 1 |

| Previous DVT or PE | 3 |

| Surgery or fracture within 1 month | 2 |

| Active cancer (treatment within 1 year or palliative) | 2 |

| Unilateral lower limb pain | 3 |

| Hemoptysis | 2 |

| Heart rate 75-94 beats/min | 3 |

| Heart rate ≥ 95 beats/min | 5 |

| Pain on deep venous palpation and unilateral edema | 4 |

Interpretation

- Low probability: 0-3 points

- Intermediate probability: 4-10 points

- High probability: ≥ 11 points

Laboratory Investigations

Laboratory investigations play a crucial role in the diagnostic workup of pulmonary embolism, although they are rarely definitive on their own. They are used to assess the likelihood of pulmonary embolism, evaluate the patient’s overall condition, and rule out other potential diagnoses.

D-dimer

D-dimer is a fibrin degradation product, a small protein fragment present in the blood after a blood clot is degraded by fibrinolysis. It’s a highly sensitive, but not specific, marker for thrombosis. D-dimer is most useful in excluding pulmonary embolism in low-risk patients.

Expected Results

- Elevated D-dimer levels are common in pulmonary embolism, as well as in other conditions involving clot formation or breakdown.

- A negative D-dimer result in a patient with a low or intermediate clinical probability of pulmonary embolism (PE) can effectively rule out the diagnosis.

- However, a positive D-dimer does not confirm pulmonary embolism, as it can be elevated in various other conditions, including:

- Pregnancy

- Malignancy

- Infection

- Recent surgery or trauma

- Advanced age

Arterial Blood Gases (ABGs)

ABGs measure the levels of oxygen, carbon dioxide, and pH in arterial blood. This test assesses the patient’s oxygenation and acid-base status. ABGs provide information about the severity of respiratory compromise and help assess the need for oxygen therapy.

Expected Results

- Hypoxemia (low PaO2) is a common finding, but it’s not always present.

- Hypocapnia (low PaCO2) due to hyperventilation is also frequently observed.

- The alveolar-arterial (A-a) gradient is often increased, reflecting the ventilation-perfusion mismatch.

- It is important to remember that ABG’s can be normal in pulmonary embolism.

Cardiac Biomarkers (Troponin and BNP)

- Troponin: Troponin is a cardiac muscle protein released into the bloodstream when there is myocardial damage. Troponin helps to risk stratify patients. Elevated troponin levels may be present in patients with PE who have right ventricular strain or injury. An elevated troponin indicates a higher risk of adverse outcomes.

- BNP (Brain Natriuretic Peptide) or NT-proBNP (N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide): BNP is a hormone released by the heart in response to ventricular stretch. Elevated BNP or NT-proBNP levels may be present in patients with PE who have right ventricular dysfunction. Similar to troponin, elevated BNP/NT-proBNP levels indicate right ventricular strain and are associated with a poorer prognosis.

Other Blood Tests

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): The CBC is usually normal in pulmonary embolism. However, mild leukocytosis (elevated white blood cell count) may be present, especially in patients with pulmonary infarction. The CBC is primarily used to rule out other causes of symptoms, such as infection.

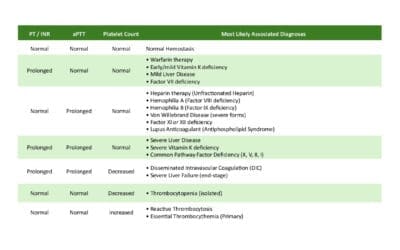

- Coagulation Studies (PT/INR, aPTT): These tests are usually normal in acute pulmonary embolism unless the patient has a preexisting coagulation disorder or is taking anticoagulant medication. These tests are performed to establish baseline coagulation parameters before initiating anticoagulant therapy.

Imaging Studies

Imaging studies are crucial for the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism (PE), providing direct visualization of the pulmonary arteries and allowing for the detection of emboli.

CT Pulmonary Angiography (CTPA)

CTPA is the gold standard imaging test for pulmonary embolism (PE). It involves injecting contrast dye into a vein and then using a CT scanner to obtain high-resolution images of the pulmonary arteries.

Expected Results

- Positive CTPA: The presence of a filling defect within the pulmonary arterial lumen, indicating an embolus. The embolus can be central or peripheral, and the size and location can be described.

- Negative CTPA: No filling defects are visualized within the pulmonary arteries.

- Incidental Findings: CTPA can also reveal other abnormalities, such as pneumonia, pleural effusion, or lung masses, which may explain the patient’s symptoms.

Advantages

- High sensitivity and specificity for pulmonary embolism.

- Rapid acquisition of images.

- Ability to visualize other thoracic structures.

Disadvantages

- Requires intravenous contrast, which may be contraindicated in patients with renal insufficiency or contrast allergy.

- Radiation exposure.

Ventilation-Perfusion (V/Q) Scan

A V/Q scan involves inhaling a radioactive gas (ventilation) and injecting a radioactive tracer (perfusion) to assess the matching of ventilation and blood flow in the lungs.

Expected Results

- High Probability: Multiple large segmental or lobar mismatches (areas of normal ventilation with absent perfusion).

- Intermediate Probability: Subsegmental mismatches, or other findings that are not clearly high or low probability.

- Low Probability: Small perfusion defects with normal ventilation, or perfusion defects that match ventilation defects.

- Normal: Normal ventilation and perfusion throughout the lungs.

Advantages

- Lower radiation exposure than CTPA.

- Useful in patients with contraindications to CT contrast.

- Useful in pregnant patients.

Disadvantages

- Lower sensitivity and specificity than CTPA.

- Interpretation can be subjective.

- Indeterminate results are common, especially in patients with preexisting lung disease.

Compression Ultrasonography of the Legs

Ultrasound imaging is used to visualize the deep veins of the legs and detect deep vein thrombosis (DVT). A positive ultrasound for DVT can support the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism (PE), particularly when CTPA or V/Q scan results are inconclusive.

Expected Results

- Positive Ultrasound: Noncompressible deep veins, indicating the presence of a thrombus.

- Negative Ultrasound: Compressible deep veins, indicating the absence of a thrombus.

Pulmonary Angiography

An invasive procedure that involves injecting contrast dye directly into the pulmonary arteries and obtaining X-ray images.

Expected Results

- Positive Pulmonary Angiogram: Direct visualization of a filling defect within the pulmonary arterial lumen.

- Negative Pulmonary Angiogram: No filling defects are visualized.

Advantages

- Historically the gold standard, and very accurate.

Disadvantages

- Invasive and carries a risk of complications.

- Rarely used in current clinical practice due to the availability of CTPA.

Chest X-ray and ECG

These are routinely used but are rarely diagnostic for pulmonary embolism (PE). Their main usage is to rule out other possible diseases. It can show things like atelectasis, pleural effusions, or a Hampton’s hump (a wedge-shaped opacity in the periphery of the lung, suggestive of pulmonary infarction).

Current PE Treatment and Management

The current PE treatment and management focus on preventing further clot formation, dissolving existing clots, and providing supportive care to stabilize the patient.

Risk Stratification

This is crucial for guiding treatment decisions. Patients are categorized based on their hemodynamic stability and the presence of right ventricular dysfunction:

- Massive PE: Hemodynamic instability (hypotension, shock, or persistent bradycardia).

- Submassive PE: Right ventricular dysfunction (evidenced by imaging or biomarkers) without hemodynamic instability.

Low-risk PE: No hemodynamic instability or right ventricular dysfunction.

Anticoagulation

This is the cornerstone of pulmonary embolism treatment, aimed at preventing further clot propagation and new clot formation. It is very important to consider the patient’s renal function when deciding which anticoagulant to use.

- Initial Anticoagulation: Low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), unfractionated heparin (UFH), or fondaparinux are commonly used for initial anticoagulation. Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) can also be used as initial therapy in selected patients.

- Long-term Anticoagulation: DOACs (rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban, dabigatran) are now often preferred for long-term anticoagulation due to their ease of use and predictable pharmacokinetics. Warfarin can be used, but requires regular INR monitoring. The duration of anticoagulation is determined by the patient’s risk factors and the presence of reversible or irreversible causes. Generally, at least 3 months are required, and longer or even life long anticoagulation is sometimes necessary.

Thrombolytic Therapy

This involves the use of medications to dissolve existing clots. Thrombolytic therapy carries a risk of bleeding complications.

- Indications: Massive pulmonary embolism with hemodynamic instability.

- Agents: Alteplase, reteplase, tenecteplase.

- Contraindications: Active bleeding, recent stroke, recent major surgery, and other conditions.

Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis or Embolectomy

These interventional procedures are considered in patients with massive or submassive pulmonary embolism with contraindications to systemic thrombolysis or persistent hemodynamic instability despite anticoagulation. These procedures should be done in centers with expertise.

- Catheter-directed thrombolysis: Involves delivering thrombolytic agents directly to the clot via a catheter.

- Mechanical thrombectomy: Involves physically removing the clot using a catheter-based device.

Supportive Care

- Oxygen Therapy: Supplemental oxygen is administered to maintain adequate oxygen saturation.

- Hemodynamic Support: Vasopressors and inotropes may be needed to maintain blood pressure and cardiac output in patients with hemodynamic instability.

- Mechanical Ventilation: May be necessary in patients with severe respiratory distress or hemodynamic instability.

IVC Filters

Inferior vena cava (IVC) filters are placed in the IVC to prevent clots from traveling to the lungs. IVC filters are generally considered temporary measures.

- Indications: Contraindications to anticoagulation, recurrent pulmonary embolism despite adequate anticoagulation, or high risk of bleeding complications.

Prevention

- Pharmacological Prophylaxis: Anticoagulants (LMWH, fondaparinux, DOACs) are used to prevent VTE in high-risk patients (e.g., surgical patients, hospitalized patients).

- Mechanical Prophylaxis: Compression stockings and intermittent pneumatic compression devices are used to prevent venous stasis.

- Early Mobilization: Encouraging early ambulation after surgery or illness reduces the risk of DVT.

Long-term Management and Follow-up

Patients who have had a pulmonary embolism require long-term follow-up to monitor for complications, such as chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH). Patients should be educated on signs and symptoms of recurrent pulmonary embolism and DVT.

Complications of Pulmonary Embolism (PE)

Even with appropriate treatment, pulmonary embolism can lead to several complications, some of which can be life-threatening.

- Pulmonary Hypertension: This is a condition of increased blood pressure in the pulmonary arteries. This disorder can cause chronic damage to the pulmonary vasculature, leading to a sustained increase in pulmonary arterial pressure. This can result in right heart strain and eventual right heart failure.

- Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension (CTEPH): CTEPH is a specific form of pulmonary hypertension that develops when organized thrombi persist in the pulmonary arteries after an acute pulmonary embolism. These persistent clots obstruct blood flow, leading to increased pulmonary vascular resistance and pulmonary hypertension. CTEPH can cause progressive dyspnea, exercise intolerance, and right heart failure. It is a severe complication that requires specialized treatment, including pulmonary thromboendarterectomy (PTE).

- Recurrent PE: Patients who have had a pulmonary embolism are at increased risk of developing another one, especially if they have ongoing risk factors or underlying thrombophilia. Recurrent pulmonary embolisms can lead to cumulative damage to the pulmonary vasculature and increase the risk of pulmonary hypertension and CTEPH. This is why long term anticoagulation is sometimes necessary.

- Right Heart Failure: Acute pulmonary embolism can cause acute right ventricular strain and failure, particularly in massive pulmonary embolism. Chronic pulmonary embolism or CTEPH can also lead to chronic right heart failure due to the sustained increase in pulmonary arterial pressure. Right heart failure can cause symptoms such as peripheral edema, jugular venous distention, and ascites.

- Pulmonary Infarction: When a pulmonary embolus obstructs a smaller, peripheral pulmonary artery, it can lead to pulmonary infarction, where the lung tissue distal to the blockage dies. This can cause pleuritic chest pain, hemoptysis, and pleural effusion. Pulmonary infarction can also lead to a small area of scarring in the lung.

- Complications from Treatment: Anticoagulation therapy can increase the risk of bleeding complications. Thrombolytic therapy carries a higher risk of major bleeding, including intracranial hemorrhage. Interventional procedures, such as catheter-directed thrombolysis or embolectomy, can also cause complications, such as bleeding, vessel injury, or infection. IVC filters can cause complications such as filter migration, thrombosis, or infection.

- Death: Massive PE can cause sudden cardiac arrest and death due to severe hemodynamic instability. Even with treatment, pulmonary embolism can contribute to mortality, especially in patients with comorbidities.

Prognosis of Pulmonary Embolism (PE)

The prognosis of pulmonary embolism (PE) varies significantly depending on several factors, including the severity of the initial event, the presence of comorbidities, and the promptness and effectiveness of treatment.

Factors Influencing Prognosis

- Hemodynamic Stability: Massive pulmonary embolism (PE) with hemodynamic instability (hypotension, shock) has the highest mortality rate, particularly within the first few hours of presentation. Submassive and low-risk pulmonary embolism (PE) generally have a better prognosis.

- Right Ventricular Dysfunction: The presence of right ventricular dysfunction, as evidenced by imaging or biomarkers, is associated with a poorer prognosis, even in patients without hemodynamic instability.

- Comorbidities: Underlying cardiovascular or pulmonary diseases, malignancy, and other comorbidities can increase the risk of complications and worsen the prognosis.

- Promptness of Diagnosis and Treatment: Early diagnosis and initiation of appropriate treatment, particularly anticoagulation or thrombolysis, significantly improve outcomes. Delays in diagnosis and treatment increase the risk of mortality and complications.

- Presence of Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension (CTEPH): The development of CTEPH is associated with a poorer long-term prognosis, as it can lead to progressive pulmonary hypertension and right heart failure.

- Recurrent PE: Recurrent PEs can lead to cumulative damage to the pulmonary vasculature and increase the risk of pulmonary hypertension and CTEPH.

- Age: Older patients tend to have a worse prognosis.

General Prognosis

- Acute Phase: The highest risk of mortality occurs within the first few hours of a massive pulmonary embolism. With prompt treatment, the mortality rate for pulmonary embolism has significantly decreased.

- Long-Term Prognosis: Most patients with low-risk or submassive pulmonary embolism who receive appropriate treatment have a good long-term prognosis. However, even after an acute pulmonary embolism, some patients may experience long-term complications, such as chronic dyspnea or exercise intolerance. CTEPH, if it develops, requires specialized care and greatly affects long term prognosis.

- Risk of Recurrence: The risk of recurrence is highest in the first few weeks after the initial event and remains elevated for several months. Long-term anticoagulation is often necessary to reduce the risk of recurrence.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Myat, A., Ahsan, A. Percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy for the treatment of acute massive pulmonary embolism: case report. Thrombosis J 5, 20 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-9560-5-20

- Demelo-Rodriguez P, Galeano-Valle F, Salzano A, Biskup E, Vriz O, Cittadini A, Falsetti L, Ranieri B, Russo V, Stanziola AA, Bossone E, Marra AM. Pulmonary Embolism: A Practical Guide for the Busy Clinician. Heart Fail Clin. 2020 Jul;16(3):317-330. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2020.03.004. PMID: 32503755.

- Essien EO, Rali P, Mathai SC. Pulmonary Embolism. Med Clin North Am. 2019 May;103(3):549-564. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2018.12.013. PMID: 30955521.

- Becattini C, Agnelli G. Risk stratification and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2016 Dec 2;2016(1):404-412. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2016.1.404. PMID: 27913508; PMCID: PMC6142437.

- Tehrani BN, Batchelor WB, Spinosa D. High-Risk Acute Pulmonary Embolism: Where Do We Go From Here? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024 Jan 2;83(1):44-46. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2023.11.001. PMID: 38171709.