TL;DR

Transfusion-associated circulatory overload or TACO is a non-immunologic transfusion reaction occurring within 6 hours that results from acute hypervolemia overwhelming the heart’s capacity, which consequently raises pulmonary capillary hydrostatic pressure (↑PCWP) and causes cardiogenic pulmonary edema.

- Causes and Risk Factors ▾: While directly triggered by the rapid infusion of a large volume of blood product, TACO primarily affects patients with compromised fluid management systems, such as those with CHF, ESRD, or individuals at the age extremes.

- Clinical and Diagnostic Hallmarks ▾: Diagnosis is supported by the acute onset of dyspnea, JVD, and often hypertension within 6 hours, complemented by CXR findings of cardiogenic edema and a highly suggestive ≥1.5-fold increase in BNP from the pre-transfusion baseline.

- Treatment and Management ▾: Immediate treatment involves stopping the transfusion, positioning the patient upright, providing respiratory support with NIPPV, and administering intravenous loop diuretics (Furosemide)

- Prevention ▾: Prevention centers on slowing infusion rates and utilizing prophylactic diuretics or split units for high-risk patients.

*Click ▾ for more information

Introduction

Transfusion-Associated Circulatory Overload (TACO) is a common and serious complication of blood transfusion, defined by new or worsening respiratory distress and evidence of circulatory overload temporally associated with the transfusion.

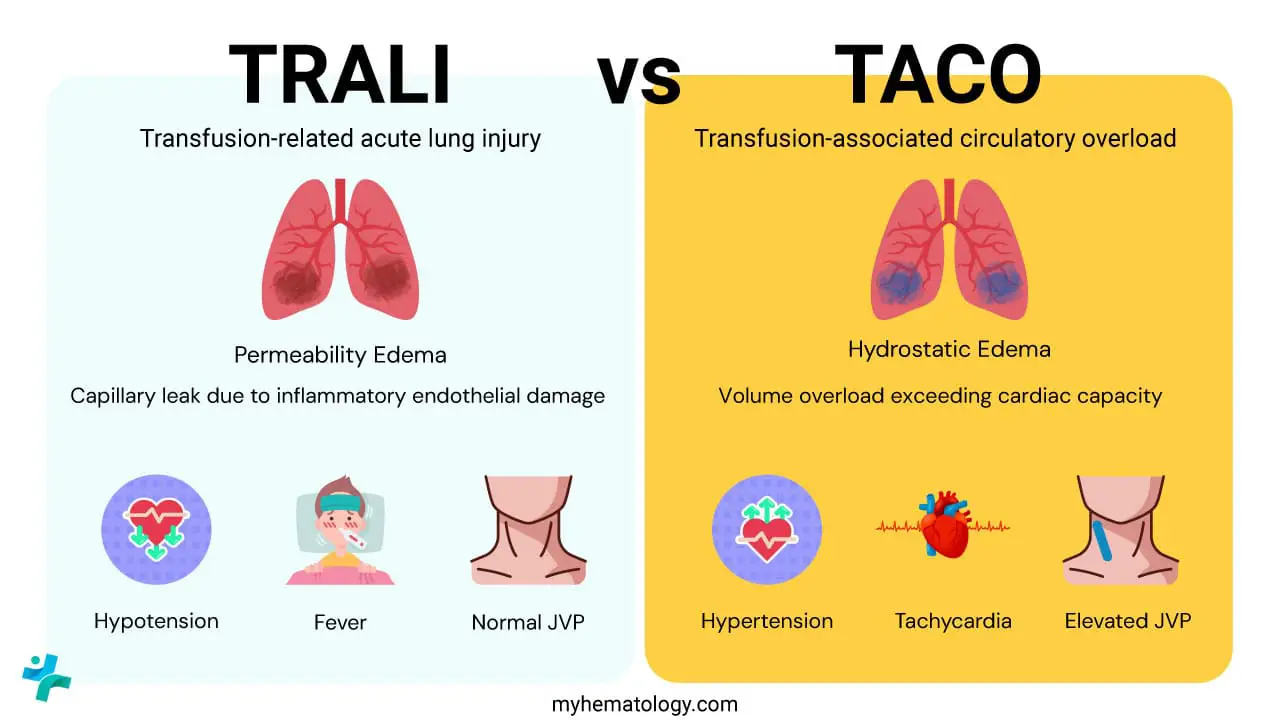

Often under-recognized or confused with Transfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury (TRALI), transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) is now the leading cause of transfusion-related mortality reported to regulatory agencies. Estimates of clinical incidence vary widely (1 – 8% of transfusions), largely due to a lack of standardization in surveillance and diagnosis.

Transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) is a state of acute pulmonary edema resulting from volume excess, rapid infusion, or diminished cardiac/renal function secondary to or exacerbated by blood product administration.

While generally lower than TRALI, TACO-related mortality is a persistent concern, making it a critical focus for patient safety initiatives by organizations like the American Association of Blood Banks (AABB).

Clinicians must differentiate TACO from TRALI, as their management differs. Transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) is volume-mediated hydrostatic pulmonary edema, while TRALI is an inflammatory, immune-mediated, non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema. Patients may occasionally present with possible bi-temporal TACO/TRALI overlap.

Pathophysiology of Transfusion-Associated Circulatory Overload

Transfusion-Associated Circulatory Overload (TACO) is fundamentally a case of acute, iatrogenic heart failure. Unlike Transfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury (TRALI), which is driven by inflammatory mediators causing capillary damage, transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) is purely a hemodynamic process caused by a simple mechanical imbalance: rapid volume infusion overwhelming the patient’s existing cardiac reserve.

The Vicious Cycle of Hypervolemia

- Rapid Volume Introduction: Blood products, even packed red blood cells (PRBCs), contain significant volumes of fluid (plasma or additive solutions). When transfused rapidly or in large quantities, this fluid directly increases the total intravascular volume.

- Inability to Compensate: In a healthy individual, the cardiovascular system can typically manage this fluid bolus. However, in high-risk patients, the heart, particularly the left ventricle (LV), has a diminished ability to effectively push this increased volume forward. The LV is stiff, failing, or simply overwhelmed.

- Increased Preload and Afterload: The increased intravascular volume directly raises the cardiac preload. Because the heart cannot handle this volume, the stroke volume plateaus or decreases, and the volume backs up into the circulation.

The Hemodynamic Cascade

The inability of the left heart to pump the blood volume leads to a rapid increase in filling pressures.

| Hemodynamic Parameter | Change ( / ↓) | Clinical Impact |

| Left Atrial Pressure (LAP) | ↑ | Reflects the pressure backlog from the failing left ventricle. |

| Pulmonary Capillary Wedge Pressure (PCWP) | ↑ | Directly correlates with LAP and is the critical driver of pulmonary edema. |

| Central Venous Pressure (CVP) | ↑ | Indicates volume overload and right heart congestion (Clinically seen as JVD). |

| Systemic Arterial Pressure | ↑ or ↓ | Often ↑ initially due to volume, but may ↓ later if cardiac output fails completely (cardiogenic shock). |

The Development of Cardiogenic Pulmonary Edema

The pathological endpoint of transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) is cardiogenic pulmonary edema, which follows the principles of Starling forces across the pulmonary capillary membrane.

- Elevated Hydrostatic Pressure (Pc): As the PCWP rises, the hydrostatic pressure inside the pulmonary capillaries (Pc) dramatically increases.

- Overwhelming the Oncotic Pressure (Πi): In a healthy lung, the plasma oncotic pressure (Πp) helps pull fluid back into the capillary. In transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO), the massively elevated Pc quickly exceeds the counteracting forces, including the plasma oncotic pressure.

- Fluid Transudation: This pressure gradient forces plasma fluid out of the capillaries and into the surrounding interstitium of the lung.

- Alveolar Flooding: As the interstitial lymphatics become overwhelmed, the fluid spills into the alveoli, impairing gas exchange, leading to ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) mismatch, and manifesting clinically as acute respiratory distress and hypoxemia. This is the definition of flash pulmonary edema.

Thus, transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) is a direct consequence of the patient’s failing heart being unable to handle an excessive fluid load, resulting in back-pressure that floods the lungs.

Contributing Factors (Stored Blood Product Effects)

Components of the transfused blood product itself may contribute to the physiologic derangements:

- Immunomodulation: Biologically active mediators (e.g., cytokines, chemokines) that accumulate during storage (Storage Lesion) may increase endothelial permeability, exacerbating fluid extravasation.

- Temperature: Rapid infusion of cold blood may induce vasospasm and transient myocardial depression in vulnerable patients.

Etiology and Patient Risk Factors

Transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) is a condition resulting from the convergence of two critical elements: the rate and volume of fluid input (the Etiology) and the patient’s ability to handle that fluid (the Risk Factors).

Causes

The direct cause of transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) is the introduction of fluid volume that exceeds the heart’s capacity to manage its return, leading to acute hypervolemia.

- Rapid Infusion Rate: This is the most significant factor. Even a moderate volume can overwhelm a compromised heart if administered too quickly. In high-risk patients, infusing a unit of packed red blood cells (PRBCs) over 90 minutes is often enough to precipitate symptoms, whereas a healthy patient might tolerate the same unit over 20 minutes.

- Large Total Volume Transfused: The total volume administered during a transfusion episode (e.g., multiple units of PRBCs or large volumes of fresh frozen plasma (FFP)) directly correlates with risk. Massive transfusion protocols greatly increase the risk of transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO).

- Co-administration of Intravenous Fluids (Co-loading): Often overlooked, the simultaneous administration of maintenance IV fluids (e.g., normal saline or crystalloids) alongside blood products contributes to the total volume load, acting as the ‘tipping point’ for a patient with borderline cardiac function.

- Composition of the Blood Product: While PRBCs are “packed,” they still contain significant amounts of additive solution (such as AS-1 or AS-3) and residual plasma, all of which contribute to the final intravascular volume.

Patient Risk Factors

Risk factors describe the underlying conditions that predispose a patient to transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) because they limit the body’s ability to excrete fluid or accommodate volume expansion.

Cardiovascular Compromise (Reduced Pump Function)

These patients have a low ejection fraction and cannot increase their stroke volume in response to increased preload.

- Congestive Heart Failure (CHF): Pre-existing heart failure, especially systolic or diastolic dysfunction, is the single greatest risk factor. The heart is operating on the flat part of the Frank-Starling curve and cannot utilize extra volume to generate more contractile force.

- Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI): Recent heart damage severely limits ventricular compliance and contractility.

- Valvular Heart Disease: Conditions like aortic or mitral regurgitation/stenosis can impair effective forward flow, causing volume to back up rapidly into the left atrium and pulmonary circulation.

Renal Impairment (Reduced Excretory Function)

These patients cannot effectively adjust their fluid balance by filtering and excreting excess volume.

- End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) or Dialysis Patients: These individuals are often anuric or oliguric and are highly sensitive to any non-dialytic fluid intake.

- Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) with Oliguria: Reduced urine output means the volume infused cannot be compensated for by renal excretion.

Age Extremes and Body Weight

- The Elderly (≥70 years): Age-related changes, including decreased cardiac compliance (stiffer ventricles) and reduced renal function, diminish cardiovascular reserve.

- Infants and Neonates: Their smaller total blood volume means that even small volumes of transfused product represent a large percentage of their total circulating volume, making them susceptible to volume shifts.

- Low Body Weight: Patients with lower body mass have less circulatory volume buffer, meaning the standard volume of a unit of blood has a proportionally greater impact on their hemodynamics.

Pre-Existing Volume Status

- Chronic Severe Anemia with Volume Expansion: Patients with long-standing anemia (e.g., certain hemoglobinopathies) may already have baseline volume expansion due to chronic physiological compensation, leaving them with minimal reserve.

- Positive Fluid Balance: Patients who have already accumulated a positive net fluid balance from previous IV fluids, feeds, or ongoing critical illness.

Clinical Presentation of TACO

TACO is a rapid-onset, life-threatening complication that requires immediate recognition. The signs and symptoms are a direct result of the acute, sudden increase in hydrostatic pressure in the pulmonary vasculature.

Timing of Onset

By definition, transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) symptoms must occur during the transfusion or within 6 hours of its completion. However, in critically ill patients or those with severe risk factors (e.g., CHF, ESRD), symptoms often begin much sooner – sometimes within the first hour of infusion.

Respiratory Signs (The Hallmark of Pulmonary Edema)

Respiratory distress is the most prominent feature and often the chief complaint, driven by acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema.

- Acute Onset of Dyspnea: The patient will suddenly report feeling short of breath. This may progress rapidly.

- Tachypnea: Increased respiratory rate as the body attempts to compensate for impaired gas exchange.

- Orthopnea and Paroxysmal Nocturnal Dyspnea (PND): While often associated with chronic heart failure, the acute appearance of these symptoms strongly suggests fluid redistribution and rising pulmonary pressures.

- Cough and Sputum: A persistent, non-productive cough is common. In severe, late-stage transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO), the patient may produce frothy, pink-tinged sputum, which is a classic sign of alveolar flooding with plasma and red blood cells.

- Auscultation Findings:

- Basal Crackles (Rales): The presence of inspiratory crackles, usually starting at the lung bases and moving superiorly, indicates fluid within the alveoli.

- Wheezing: May occur due to compression of small airways by the interstitial edema.

- Objective Measures:

- Hypoxemia: Decreased peripheral O2 saturation (SpO2) requiring supplemental oxygen.

- Respiratory Failure: In severe cases, patients may progress to full respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilatory support.

Circulatory and Cardiovascular Signs (Evidence of Volume Overload)

These signs confirm the hypervolemic state and distinguish transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) from other transfusion reactions that cause isolated lung injury (like TRALI, which is non-cardiogenic).

- Hypertension (Initial Phase): The initial influx of fluid often increases the circulating volume, leading to a temporary rise in systolic blood pressure. This is a crucial early sign.

- Tachycardia: The heart rate increases as the heart attempts to improve cardiac output to manage the increased volume and compensate for hypoxemia.

- Elevated Central Venous Pressure (↑ CVP): This is the key physical finding of volume overload.

- Jugular Venous Distension (JVD): Observed clinically as a distended neck vein, indicating elevated pressure backing up into the systemic circulation (right heart failure).

- Edema:

- Peripheral Edema: Exacerbation of pre-existing edema or new dependent edema.

- Positive Fluid Balance: A measurable, rapid increase in weight (often ≥500 grams).

- Late-Stage Manifestations: If not managed, the heart may decompensate entirely, leading to hypotension and features of cardiogenic shock.

Diagnosis is primarily clinical, supported by standardized criteria such as the International Society of Blood Transfusion (ISBT) definition or the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) surveillance case definition. The key is the temporal relationship between the transfusion and the onset of symptoms.

| Clinical Feature | Transfusion-Associated Circulatory Overload (TACO) Characteristic |

| Onset | Acute, typically within 6 hours of cessation or during the transfusion. |

| Respiratory Distress | Dyspnea, orthopnea, cough, hypoxemia, tachypnea. |

| Circulatory Overload | Evidence of elevated CVP: Tachycardia, acute weight gain, jugular venous distension (JVD), S3 gallop, peripheral edema. |

| Radiology (CXR) | Evidence of cardiogenic pulmonary edema: Kerley B lines, pleural effusions, or enlarged cardiac silhouette. |

| Biomarkers | Elevated B-type Natriuretic Peptide (BNP) or N-terminal pro-BNP (NT-proBNP) is highly suggestive, though not definitive, especially if baseline is available for comparison. |

Key Laboratory Investigations of TACO

Brain Natriuretic Peptide (BNP) / N-terminal pro-BNP (NT-proBNP)

These are the most valuable blood tests for distinguishing transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) (cardiogenic) from TRALI (non-cardiogenic).

BNP and NT-proBNP are hormones released by the ventricles in response to myocardial wall stress and stretching – this is what happens during acute volume overload.

While baseline levels are often high in patients with pre-existing heart failure, a significant increase in BNP from the pre-transfusion level to the post-reaction level is highly suggestive of transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO). A commonly accepted threshold is a 1.5-fold increase in the BNP level.

Other Basic Labs

- Electrolytes and Renal Function: BUN and Creatinine may be monitored, especially in patients with ESRD, to assess renal function and fluid clearance status.

Imaging and Functional Studies

Chest X-Ray (CXR)

The CXR is essential for confirming pulmonary edema and evaluating cardiac status in transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO).

- Pulmonary Vascular Congestion: Prominence of the upper lobe vessels (cephalization).

- Interstitial Edema: Peribronchial cuffing, Kerley B-lines (short horizontal lines representing fluid in the interlobular septa).

- Bilateral Alveolar Edema: “Fluffy,” ill-defined opacities often in a butterfly or bat-wing pattern, primarily radiating from the hilum.

- Cardiomegaly: Enlarged cardiac silhouette (if chronic CHF is present).

- Pleural Effusions: Often present and bilateral.

Bedside Echocardiography (or POCUS – Point-of-Care Ultrasound)

A rapid, non-invasive assessment that is becoming standard in the workup of acute transfusion reactions.

- Cardiac Assessment: Can rapidly assess left ventricular function (ejection fraction) and identify new or worsening diastolic dysfunction.

- Lung Ultrasound: Used to identify B-lines (comet-tail artifacts), which represent interstitial fluid (pulmonary edema). A greater number of B-lines correlates with the severity of alveolar-interstitial syndrome.

- IVC Assessment: Measurement of the inferior vena cava (IVC) diameter and its collapsibility index can provide a dynamic estimation of volume status and CVP.

Differentiation from TRALI

This is the most crucial diagnostic step, as treatment is opposite: transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) requires diuresis, while TRALI may be harmed by diuresis.

| Feature | TACO (Transfusion-Associated Circulatory Overload) | TRALI (Transfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury) |

| Pathogenesis | Hydrostatic (Volume Overload/Heart Failure) | Inflammatory/Permeability (Capillary Damage) |

| Hemodynamics | Elevated CVP and PCWP (High pressures) | Normal CVP and PCWP (Normal pressures) |

| BNP Change | ↑ (Often 1.5x increase) | Normal or minimally ↑ |

| CXR Findings | Cardiomegaly, Pulmonary Vascular Congestion, Effusions | Normal heart size, Absence of congestion/effusions |

| Response to Diuretics | Rapid and favorable improvement | Poor or detrimental response |

In cases where both transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) and TRALI criteria are met (a condition called TACO-TRALI overlap), the treatment approach should focus on aggressive supportive care while cautiously attempting diuresis if volume overload is strongly suspected.

Management and Treatment Protocols

Treatment of transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) focuses on reducing intravascular volume and supporting oxygenation.

Immediate Measures

- Stop/Slow Transfusion: Immediately stop the transfusion, or in mild cases, significantly slow the rate. Maintain IV access.

- Respiratory Support: Apply supplemental oxygen. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) or intubation and mechanical ventilation may be required in severe hypoxemia.

- Diuresis: Administer a loop diuretic, such as Furosemide (e.g., 20–40 mg IV), to achieve a rapid reduction in preload and fluid excretion.

- Positioning: Place the patient in an upright (Fowler’s) position to decrease venous return.

- Vasodilators (If needed): In patients with severe transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) accompanied by significant hypertension and signs of heart failure, vasodilators like intravenous nitroglycerin may be used.

Management in Special Populations

- Patients with (Dialysis Patients): Diuretics are ineffective in anuric or oliguric patients. Management of transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) involves supportive care and prompt arrangement for urgent dialysis (hemofiltration or ultrafiltration) to remove the excess fluid mechanically. Diuretic administration should be avoided as it only adds volume and can cause ototoxicity without providing benefit.

- Hypotension: If the patient develops signs of hypotension or cardiogenic shock, diuretics must be used cautiously or withheld entirely, and the focus shifts to inotropic support (e.g., Dopamine, Dobutamine) to improve cardiac contractility.

Prevention Strategies (The Gold Standard)

Prevention is most important in transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) and involves adjusting the transfusion protocol based on the patient’s individual risk profile.

- Risk Stratification: Prior to transfusion, assess all patients for cardiac and renal risk factors.

- Slower Infusion Rate: Transfuse units at a slower rate for at-risk patients (e.g., 1 unit of packed red blood cells over 4 hours).

- Volume Adjustment: Consider aliquoting blood products (e.g., dividing one unit into 2–4 smaller transfusions).

- Prophylactic Diuresis: Administer 20 mg of IV Furosemide before or between units to maintain a euvolemic state in high-risk patients.

- Strict Monitoring: Meticulous monitoring of fluid input/output, vital signs, and daily weights is essential throughout the transfusion period.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How is TACO officially reported?

Transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) is a reportable adverse event in many jurisdictions (e.g., to the FDA in the U.S. and relevant authorities internationally). Clinicians must document the event, follow institutional reporting guidelines, and notify the Transfusion Service/Blood Bank for investigation.

Can TACO and TRALI occur simultaneously?

Yes, a mixed or “possible bi-temporal TACO/TRALI overlap” syndrome is recognized. Patients present with features of both volume overload and non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema. Management requires careful balancing of diuresis (for transfusion-associated circulatory overload) against maintaining mean arterial pressure (MAP) and minimizing further lung injury (for TRALI).

Does component type matter for TACO risk?

Yes. Any product containing a substantial fluid volume poses a risk for transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO). This includes packed red blood cells (PRBCs), fresh frozen plasma (FFP), and platelets. PRBCs are most common due to their frequency of use, but rapid FFP infusion carries a high risk because it is nearly pure volume.

Glossary of Medical Terms

Alveolar-Capillary Barrier: The delicate biological membrane in the lungs across which gas exchange (oxygen and carbon dioxide) occurs. Damage or excessive pressure here leads to fluid leakage.

Cardiogenic Pulmonary Edema: Pulmonary edema caused specifically by increased pressure in the heart (usually the left ventricle) leading to increased hydrostatic pressure in the pulmonary capillaries.

Hydrostatic Pressure: The pressure exerted by a fluid against the walls of its container (in this case, the blood vessels). High hydrostatic pressure in capillaries forces fluid out.

NIPPV: Non-Invasive Positive Pressure Ventilation. Respiratory support delivered via a mask (e.g., BiPAP or CPAP) to help push fluid back out of the alveoli and improve oxygenation.

Preload: The amount of ventricular stretch at the end of diastole. It is determined by the volume of blood returning to the heart. High preload increases stroke work.

Storage Lesion: Biochemical and functional changes that occur in blood components (e.g., red blood cells, plasma) during refrigerated storage, including the accumulation of bioactive mediators.

TRALI: Transfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury. A life-threatening, non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema caused by immune reactions in response to transfused blood products.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Semple, J. W., Rebetz, J., & Kapur, R. (2019). Transfusion-associated circulatory overload and transfusion-related acute lung injury. Blood, 133(17), 1840–1853. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2018-10-860809

- Gosmann, F., Nørgaard, A., Rasmussen, M. B., Rahbek, C., Seeberg, J., & Møller, T. (2018). Transfusion-associated circulatory overload in adult, medical emergency patients with perspectives on early warning practice: a single-centre, clinical study. Blood transfusion = Trasfusione del sangue, 16(2), 137–144. https://doi.org/10.2450/2017.0228-16

- Smith C. M. (2023). CE: Recognizing Transfusion-Associated Circulatory Overload. The American journal of nursing, 123(11), 34–41. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000995356.33506.f5

- Klanderman, R. B., Bosboom, J. J., Migdady, Y., Veelo, D. P., Geerts, B. F., Murphy, M. F., & Vlaar, A. P. J. (2019). Transfusion-associated circulatory overload-a systematic review of diagnostic biomarkers. Transfusion, 59(2), 795–805. https://doi.org/10.1111/trf.15068