TL;DR

Dendritic cells (DCs) are the most potent antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that are crucial for initiating and regulating immune responses. Immature DCs migrate to peripheral tissues for antigen capture.

Classification ▾: Major subsets include cDCs (cDC1s and cDC2s) and pDCs.

Morphology ▾: Characteristic dendritic projections increase surface area for antigen capture.

Functions of Dendritic Cells ▾:

- Antigen capture and processing.

- Antigen presentation to T cells (MHC class I and II).

- T cell activation and polarization.

- Immune tolerance induction.

- Innate immune functions (e.g., IFN-α/β production by pDCs).

Causes of Alterations in Dendritic Cell Numbers and Function (Clinical Significance) ▾:

- Dendrocytosis: Infections, autoimmune diseases, and some cancers.

- Dendropenia: Immunodeficiency syndromes, some cancers, and immunosuppressive therapies.

- Functional alterations are crucial, including hyperactivation, dysfunction, and impaired antigen presentation.

- Flow cytometry is the gold standard for identifying and quantifying DC subsets.

- Other techniques include microscopy, functional assays, and emerging technologies.

*Click ▾ for more information

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs) are a type of immune cell that plays a critical role in initiating and regulating immune responses. They act as sentinels, constantly patrolling the body for foreign invaders like bacteria, viruses, and other pathogens.

Overview of the immune system

The immune system is a complex network of cells, tissues, and organs that work together to defend the body against harmful invaders like bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. It’s broadly divided into two interconnected systems.

Innate Immune System

This is the body’s first line of defense, providing rapid, non-specific responses to pathogens.

Key components include:

- Physical barriers: Skin, mucous membranes, and stomach acid prevent pathogens from entering the body.

- Immune cells: Phagocytes (like macrophages and neutrophils) engulf and destroy pathogens. Natural killer (NK) cells kill infected or cancerous cells.

- Inflammation: A process that helps recruit immune cells to the site of infection and promote tissue repair.

Adaptive Immune System

This system provides a more specific and long-lasting response to pathogens. It’s like a specialized security force that can be trained to recognize and target specific threats.

Key components include:

- Lymphocytes

- B cells: Produce antibodies that bind to pathogens and neutralize them.

- T cells: Directly kill infected cells or help activate other immune cells.

- Antigen presentation: Immune cells called antigen-presenting cells (APCs), such as dendritic cells, capture and process antigens (substances that trigger an immune response) and present them to T cells, initiating an adaptive immune response.

- Immunological memory: After encountering a pathogen, the adaptive immune system “remembers” it, allowing for a faster and stronger response upon subsequent exposure. This is the basis of vaccination.

Interplay between innate and adaptive immunity

The innate and adaptive immune systems work together to provide comprehensive protection against pathogens. The innate immune system initiates the initial response and helps activate the adaptive immune system. The adaptive immune system provides a more specific and long-lasting response, enhancing the effects of the innate immune system.

Dendritic Cell Classification

Dendritic cells (DCs) are a specialized type of immune cell that plays a crucial role in initiating and regulating immune responses. They are often referred to as the “sentinels” of the immune system because they are strategically located throughout the body, in tissues like the skin, lungs, and gut, where they can effectively capture foreign invaders like bacteria, viruses, and other pathogens.

Dendritic cells (DCs) are the most potent antigen-presenting cells (APCs) in the immune system. APCs are cells that process antigens (substances that can trigger an immune response) and present them on their surface to T cells, which are critical components of the adaptive immune system.

They are characterized by their unique morphology, with numerous cytoplasmic projections called dendrites, and their exceptional capacity to capture, process, and present antigens to T cells, leading to T cell activation and the development of immunity or tolerance.

Differences between dendritic cells and other leukocytes.

| Feature | Dendritic Cells (DCs) | Neutrophils | Macrophages | Lymphocytes (B & T cells) |

| Primary Function | Antigen presentation to T cells, initiating adaptive immunity | Phagocytosis of pathogens, especially bacteria; inflammation | Phagocytosis, antigen presentation, tissue repair, inflammation | Adaptive immunity: B cells (antibody production), T cells (cell-mediated immunity) |

| Antigen Presentation | Most potent APCs: Unique ability to activate naive T cells; express high levels of MHC I & II, costimulatory molecules | Can present antigens, but less efficient than DCs | Professional APCs, important in later stages of infection | Do not typically function as APCs in the same way as DCs or macrophages |

| Morphology | Characteristic dendritic projections (dendrites) | Multi-lobed nucleus, granular cytoplasm | Large, variable shape, may have pseudopodia | Relatively small, round cells with large nucleus |

| Origin | Myeloid (mostly) and lymphoid progenitors | Myeloid progenitor | Myeloid progenitor (monocytes) | Lymphoid progenitor |

| Location | Found in most tissues (especially at interfaces with external environment), migrate to lymph nodes | Circulate in blood, recruited to sites of infection | Reside in tissues, can be recruited to sites of infection | Reside in lymphoid organs (lymph nodes, spleen, etc.), circulate in blood and lymph |

| Lifespan | Relatively long-lived (weeks to months) | Short-lived (days) | Long-lived (months to years) | Variable (days to years, depending on subtype) |

| Key Markers | CD11c, MHC II, CD80/86 (after activation); specific markers for subsets (e.g., CD123 for pDCs) | CD15, CD16 | CD14, CD68 | B cells: CD19, CD20; T cells: CD3, CD4 (helper T cells) or CD8 (cytotoxic T cells) |

Major Subsets of Dendritic Cells

As dendritic cells (DCs) are a diverse population of immune cells with specialized functions in initiating and regulating immune responses, they are broadly classified into major subsets based on their origin, phenotype, and function.

Conventional/Myeloid Dendritic Cells (cDCs)

Conventional/Myeloid dendritic cells (cDCs) are the “classical” dendritic cells (DCs) , primarily derived from myeloid progenitors in the bone marrow. They are highly efficient at capturing, processing, and presenting antigens to T cells, initiating adaptive immune responses.

cDCs can be further divided into two main subsets:

- cDC1s

- Specialized in cross-presentation, a process by which they present exogenous antigens (from outside the cell) on MHC class I molecules, which are typically used to present endogenous antigens (from inside the cell). This is crucial for activating cytotoxic T cells (CD8+ T cells), which kill infected or cancerous cells.

- Important for anti-tumor immunity and defense against intracellular pathogens (e.g., viruses).

- Characterized by expression of markers like CD141 (BDCA-3) in humans and CD103 in mice.

- cDC2s

- Primarily present antigens on MHC class II molecules to helper T cells (CD4+ T cells), which help activate other immune cells and regulate immune responses.

- Important for initiating Th1, Th2, and Th17 responses, which are involved in different types of immune responses (e.g., cell-mediated immunity, humoral immunity, and defense against extracellular pathogens).

- Characterized by expression of markers like CD1c (BDCA-1) in humans.

Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells (pDCs)

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) are a distinct subset of dendritic cells (DCs) that share some features with plasma cells (antibody-producing cells). They are a major source of type I interferons (IFN-α/β), which are crucial for antiviral immunity. pDCs are activated by viral nucleic acids (DNA or RNA) through Toll-like receptors (TLRs), leading to massive production of IFN-α/β. They also play a role in linking innate and adaptive immunity by presenting antigens to T cells, although their antigen-presenting capacity is generally considered less potent than that of cDCs. They are characterized by expression of markers like CD123 (IL-3 receptor) and BDCA-2 (CD303).

Other Specialized Dendritic Cells

In addition to the major subsets mentioned above, there are other specialized DCs found in specific tissues.

- Langerhans cells: Found in the epidermis of the skin, they are involved in skin immunity and tolerance.

- Interstitial DCs: Located in various organs, they play a role in local immune surveillance and tolerance.

Morphology of Dendritic Cells

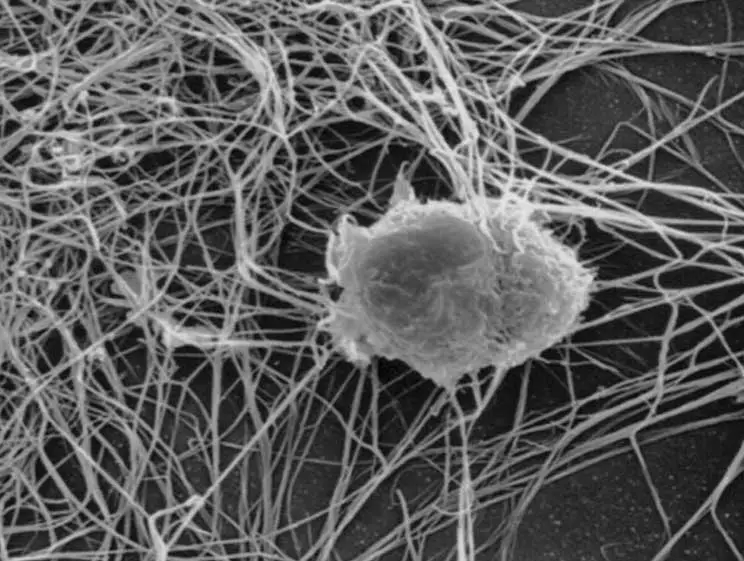

Dendritic cells (DCs) are named for their distinctive morphology, which is crucial to their function as antigen-presenting cells (APCs).

Microscopic Appearance

Light Microscopy: In their immature state, dendritic cells (DCs) may appear somewhat rounded or irregular in shape. Upon activation and maturation, they develop characteristic cytoplasmic projections called dendrites, which give them a “star-like” or “tree-like” appearance. These dendrites are dynamic structures that constantly extend and retract, allowing DCs to sample a large area of their surroundings.

Electron Microscopy: The dendrites appear as thin, elongated extensions of the cytoplasm, containing various organelles like mitochondria, ribosomes, and endosomes. The cell surface is highly irregular, with numerous folds and invaginations that increase the surface area for antigen capture.

Dendrites facilitate various mechanisms of antigen uptake, including:

- Phagocytosis: Engulfment of large particles, such as bacteria or cellular debris.

- Macropinocytosis: Ingestion of extracellular fluid containing dissolved antigens.

- Receptor-mediated endocytosis: Uptake of specific antigens that bind to receptors on the DC surface.

Characteristics of the major dendritic cell subtypes.

| Feature | Immature cDCs | Mature cDCs | cDC1s | cDC2s | pDCs |

| Overall Shape | Rounded or irregular | Highly irregular | Elongated/slender dendrites | Broader/leaf-like dendrites | Rounded, plasmacytoid |

| Dendrites | Few, short, stubby | Numerous, long, highly branched | More elongated and slender | More irregular, broader, leaf-like | Few, short |

| Cell Body | More rounded | Irregular | – | – | Smaller, rounded |

| Cytoplasm | – | – | – | – | Abundant, may contain prominent endoplasmic reticulum |

| Endocytic Activity | High | Reduced | – | – | – |

| T cell Activation Potential | Low | High | High (especially CD8+ T cells via cross-presentation) | High (especially CD4+ T cells) | Lower compared to cDCs |

| Key Surface Markers | MHC II, CD11c | MHC II (high), CD11c, CD80/86 (high) | CD11c, MHC II, CD141 (BDCA-3), CD103 (some), XCR1 | CD11c, MHC II, CD1c (BDCA-1) | CD123 (IL-3R), BDCA-2 (CD303), TLR7, TLR9 |

Development of Dendritic Cells and Reference Range

Dendritic cells (DCs) originate from hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in the bone marrow. These HSCs differentiate into various progenitor cells, including common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) and common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs), which can both give rise to dendritic cells (DCs).

The development of dendritic cells (DCs) is tightly regulated by a network of transcription factors and cytokines. Key transcription factors involved include PU.1, IRF8, BATF3 (for cDC1s), and E2-2 (for pDCs). Cytokines like FLT3L and GM-CSF play crucial roles in promoting DC differentiation and survival.

Immature dendritic cells (DCs) are released from the bone marrow into the bloodstream and migrate to peripheral tissues, such as the skin, lungs, and gut. This migration is crucial for immune surveillance, allowing dendritic cells (DCs) to capture antigens in these tissues.

The migration process is guided by various factors:

- Adhesion molecules: These molecules help dendritic cells (DCs) attach to blood vessel walls and move into tissues.

- Chemokines: These chemoattractant molecules, such as CCL2, CCL3, and CCL5, attract DCs to specific tissues.

- Chemokine receptors: DCs express receptors like CCR2 and CCR5 that bind to chemokines and guide their migration.

Once in the tissues, immature DCs reside in strategic locations, such as epithelial layers and in interstitial spaces, where they can effectively capture antigens.

The normal reference range of dendritic cells (DCs) in adults is 0.16 – 0.68% of peripheral blood leukocytes, 0.55 – 1.63% mononuclear cells and 13 – 37 x 106/L of blood.

Functions of Dendritic Cells

Antigen Capture and Processing

Antigen Capture: Dendritic cells (DCs) are strategically located in peripheral tissues (skin, mucosa, etc.) to encounter pathogens and foreign substances. They employ various mechanisms to capture antigens:

- Phagocytosis: Engulfment of large particles like bacteria and cellular debris.

- Macropinocytosis: Ingestion of extracellular fluid containing dissolved antigens.

- Receptor-mediated endocytosis: Uptake of specific antigens bound to receptors on the DC surface.

Antigen Processing: Once captured, antigens are processed within dendritic cells (DCs) into smaller peptides. This involves:

- Proteasomal pathway: Processing of intracellular antigens in the cytoplasm.

- Lysosomal pathway: Processing of extracellular antigens in endosomes/lysosomes.

Antigen Presentation

Processed peptides are loaded onto Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) molecules:

- MHC class I: Presents peptides to CD8+ T cells (cytotoxic T cells), leading to the destruction of infected cells.

- MHC class II: Presents peptides to CD4+ T cells (helper T cells), which regulate immune responses.

- Cross-presentation: A unique ability of some DCs (especially cDC1s) to present exogenous antigens on MHC class I, enabling the activation of CD8+ T cells against extracellular pathogens or tumor cells.

T Cell Activation and Polarization

T cell activation: Mature dendritic cells (DCs) migrate to lymph nodes, where they present processed antigens to T cells. This interaction, along with costimulatory signals (CD80/86), activates T cells.

T cell polarization: DCs influence the differentiation of CD4+ T cells into different subsets (Th1, Th2, Th17, Tregs) by producing specific cytokines:

- IL-12: Promotes Th1 differentiation (cell-mediated immunity).

- IL-4: Promotes Th2 differentiation (humoral immunity).

- TGF-β: Promotes Treg differentiation (immune tolerance).

Immune Tolerance

Dendritic cells (DCs) play a critical role in maintaining immune tolerance, preventing autoimmune reactions.

- Presentation of self-antigens: DCs present self-antigens to T cells, leading to T cell inactivation (anergy) or the development of regulatory T cells (Tregs) that suppress immune responses.

- Production of tolerogenic factors: DCs can produce factors like IL-10 and TGF-β, which promote immune tolerance.

Other Functions

- Innate immunity: pDCs produce large amounts of type I interferons (IFN-α/β) in response to viral infections, providing antiviral defense.

- Inflammation: DCs can produce pro-inflammatory cytokines that contribute to inflammation.

- Tissue homeostasis: Some tissue-resident DCs contribute to tissue repair and maintenance.

Alterations in Dendritic Cell Numbers and Function (Clinical Significance)

Elevated DCs (Dendrocytosis)

Dendrocytosis refers to an increase in the number of dendritic cells (DCs), particularly in the peripheral blood or certain tissues. It’s not a disease itself but rather a sign of an underlying condition. Causes of dendrocytosis includes:

Infections

- Viral infections: Many viral infections, such as HIV, cytomegalovirus (CMV), and hepatitis viruses, can lead to increased DC numbers. This is often due to the activation of DCs by viral components, leading to their proliferation and mobilization.

- Bacterial infections: Some bacterial infections, such as tuberculosis and sepsis, can also cause dendrocytosis.

- Fungal infections: Certain fungal infections can also trigger an increase in DCs.

Autoimmune Diseases

In autoimmune diseases, the immune system mistakenly attacks the body’s own tissues. This can lead to chronic inflammation and activation of DCs, resulting in increased DC numbers.

Examples of autoimmune diseases associated with dendrocytosis include:

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Sjögren’s syndrome

Cancers

Some cancers, particularly hematological malignancies (cancers of the blood), can be associated with increased DC numbers. In some cases, the tumor cells themselves may secrete factors that stimulate DC proliferation. In other cases, the immune system’s response to the tumor can lead to increased DC activation and numbers.

Inflammatory Conditions

Chronic inflammatory conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and psoriasis, can also lead to dendrocytosis. The inflammatory environment can stimulate DC activation and proliferation.

Other Causes

- Vaccination: Vaccination can transiently increase DC numbers as part of the normal immune response.

- Transplantation: Dendrocytosis can occur after organ transplantation, potentially related to immune responses against the transplanted organ.

Decreased DCs (Dendropenia)

Dendropenia, a decrease in the number of dendritic cells (DCs), is less commonly studied than dendrocytosis (increased DCs). However, it can have significant implications for immune function. Causes of dendropenia includes:

Immunodeficiency Syndromes

- Primary immunodeficiencies: These are genetic disorders that affect the development or function of the immune system. Some primary immunodeficiencies can lead to impaired DC development or survival, resulting in dendropenia.

- Secondary immunodeficiencies: These are acquired conditions that weaken the immune system.

- HIV infection: HIV infects and destroys CD4+ T cells, which are crucial for DC maturation and function. This can indirectly lead to dendropenia.

- Malnutrition: Severe malnutrition can impair immune cell development, including DCs.

Cancers

Some cancers, particularly certain hematological malignancies (e.g., acute myeloid leukemia), can be associated with decreased DC numbers. Tumor cells may release factors that inhibit DC development or promote their apoptosis. Chemotherapy and radiation therapy, used to treat cancer, can also damage DCs and lead to dendropenia.

Immunosuppressive Therapies

Immunosuppressive drugs, used to prevent organ rejection after transplantation or to treat autoimmune diseases, can suppress immune cell function, including DCs. Corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors (e.g., cyclosporine, tacrolimus), and other immunosuppressive agents can contribute to dendropenia.

Infections

While some infections can cause dendrocytosis, others can lead to dendropenia. For example, some viral infections can directly infect and destroy DCs.

Other Causes

- Aging: Some studies suggest that DC numbers may decline with age, contributing to immunosenescence (age-related decline in immune function).

- Certain medications: Some medications, other than immunosuppressive drugs, may also have negative effects on DC numbers or function.

Functional Alterations

Functional alterations of DCs are crucial in various diseases, often more important than just numerical changes. In dendrocytosis, DCs may be hyperactivated or dysfunctional, contributing to inflammation or immune evasion. In dendropenia, the main consequence is impaired antigen presentation and T cell activation, leading to weakened immune responses.

In Dendrocytosis (Increased DC Numbers)

Infections

- Increased activation and maturation: Dendritic cells (DCs) are often hyperactivated in infections, leading to increased expression of MHC molecules, costimulatory molecules (CD80/86), and pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-12, TNF-α). This can lead to strong T cell responses, but also potentially excessive inflammation.

- Impaired antigen processing or presentation: In some chronic infections, pathogens may interfere with DC antigen processing or presentation, hindering effective immune clearance.

Autoimmune Diseases

- Autoreactive antigen presentation: Dendritic cells (DCs) present self-antigens to T cells, triggering autoimmune responses.

- Increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines: Dendritic cells (DCs) contribute to chronic inflammation by producing cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6.

- Impaired tolerance induction: Dendritic cells (DCs) may have a reduced ability to induce T cell tolerance, further perpetuating autoimmunity.

Cancers

- Tumor-induced DC dysfunction: Tumor cells can release factors that impair DC maturation, antigen presentation, and T cell activation. This can contribute to immune evasion by the tumor.

- Increased tolerogenic DCs: In some cancers, there may be an increase in DCs with tolerogenic properties, promoting immune suppression in the tumor microenvironment.

In Dendropenia (Decreased DC Numbers)

Immunodeficiency Syndromes

- Impaired antigen presentation: Reduced DC numbers directly limit the ability to present antigens to T cells, leading to weakened immune responses.

- Defective T cell activation: Even if some DCs are present, they may have impaired ability to activate T cells due to defects in costimulatory molecule expression or cytokine production.

- Reduced type I interferon production (especially in pDC deficiency): This compromises antiviral immunity.

Cancers

- Reduced anti-tumor immunity: Decreased DC numbers can impair the ability of the immune system to recognize and attack tumor cells.

Immunosuppressive Therapies

- Impaired DC maturation and function: Immunosuppressive drugs can directly inhibit DC maturation, antigen presentation, and T cell activation.

Laboratory Investigations

Laboratory investigations for dendrocytosis and dendropenia primarily focus on enumerating and characterizing dendritic cells (DCs).

Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometry is the gold standard for identifying and quantifying DC subsets. It uses fluorescently labeled antibodies that bind to specific surface markers on DCs, allowing for the identification and quantification of different DC populations.

Immunohistochemistry

Uses antibodies to detect DC markers in tissue sections, providing information about DC location and distribution.

Functional Assays

- Mixed leukocyte reaction (MLR): Measures the ability of DCs to stimulate T cell proliferation.

- Cytokine production assays: Measures the production of cytokines by DCs in response to various stimuli.

- Antigen presentation assays: Assesses the ability of DCs to present antigens to T cells.

Emerging Techniques

- Single-cell RNA sequencing: Provides a high-resolution view of DC heterogeneity and function.

- Mass cytometry (CyTOF): Allows for the simultaneous measurement of a large number of surface and intracellular markers on single cells.

Therapeutic Targeting of Dendritic Cells

Dendritic cells (DCs), with their crucial role in initiating and regulating immune responses, have become a prime target for immunotherapy. Therapeutic strategies aim to harness the power of DCs to fight diseases like cancer, infections, and autoimmune disorders.

DC-Based Vaccines for Cancer Immunotherapy

DC-based vaccines aim to stimulate anti-tumor immunity by loading DCs with tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) and then reintroducing them into the patient. The DCs then present these TAAs to T cells, activating them to recognize and kill tumor cells.

Types of DC vaccines

- Ex vivo loading: DCs are isolated from the patient’s blood, matured in vitro, and loaded with TAAs (e.g., tumor lysates, peptides, RNA). These loaded DCs are then injected back into the patient.

- In vivo targeting: Strategies to deliver TAAs directly to DCs in vivo, using antibodies, nanoparticles, or other delivery systems that target DC-specific receptors.

Targeting DCs in Autoimmune Diseases

In autoimmune diseases, the goal is to tolerize the immune system to self-antigens. Targeting DCs can help achieve this by promoting tolerance induction rather than immune activation.

Strategies

- Inducing tolerogenic DCs: Using agents like vitamin D3, corticosteroids, or gene modification to induce DCs with tolerogenic properties (e.g., producing IL-10, expressing inhibitory molecules).

- Blocking DC activation: Using drugs that inhibit DC maturation or activation, reducing their ability to stimulate autoreactive T cells.

Targeting DCs in Infections

In chronic infections or infections with immune evasion mechanisms, targeting DCs can help enhance immune responses and clear the pathogen.

Strategies

- Activating DCs: Using Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists or other immunostimulatory agents to enhance DC activation and antigen presentation.

- Improving antigen delivery to DCs: Using delivery systems to target pathogen-derived antigens to DCs, enhancing their ability to initiate protective immune responses.

Other Therapeutic Approaches

- DC-based cell therapies: Using genetically modified DCs to express specific antigens or therapeutic molecules.

- Targeting DC migration: Modulating DC migration to lymph nodes or sites of inflammation to enhance or suppress immune responses.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and is specifically targeted towards medical students. It is not intended to be a substitute for informed professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information presented here is derived from credible medical sources and is believed to be accurate and up-to-date, it is not guaranteed to be complete or error-free. See additional information.

References

- Haller Hasskamp J, Zapas JL, Elias EG. Dendritic cell counts in the peripheral blood of healthy adults. Am J Hematol. 2005 Apr;78(4):314-5. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20296. PMID: 15795906.

- Patente TA, Pinho MP, Oliveira AA, Evangelista GCM, Bergami-Santos PC, Barbuto JAM. Human Dendritic Cells: Their Heterogeneity and Clinical Application Potential in Cancer Immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2019 Jan 21;9:3176. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.03176. PMID: 30719026; PMCID: PMC6348254.

- Théry C, Amigorena S. The cell biology of antigen presentation in dendritic cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2001 Feb;13(1):45-51. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00180-1. PMID: 11154916.

- Balan S, Saxena M, Bhardwaj N. Dendritic cell subsets and locations. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2019;348:1-68. doi: 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2019.07.004. Epub 2019 Sep 3. PMID: 31810551.

- Lee YS, Radford KJ. The role of dendritic cells in cancer. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2019;348:123-178. doi: 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2019.07.006. Epub 2019 Aug 1. PMID: 31810552.